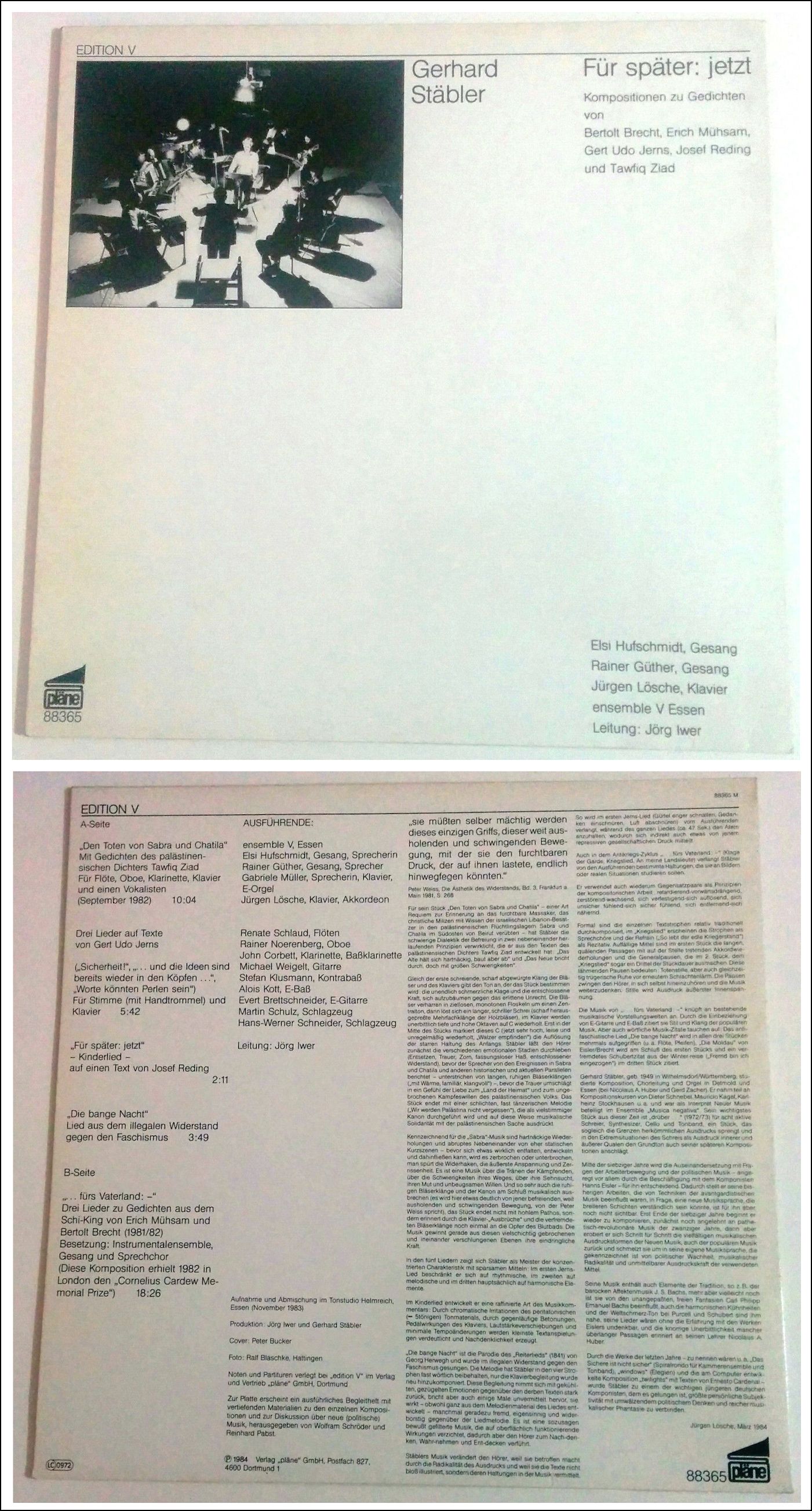

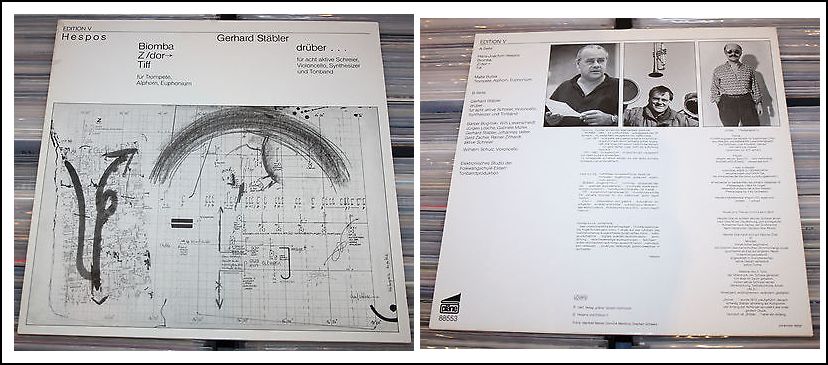

Gerhard Stäbler was born on July 20, 1949, in the south German town of Wilhelmsdorf, close to Ravensburg. He studied composition with Nicolaus A. Huber in Detmold and Organ with Gerd Zacher in Essen. Since then, he has been living as an active freelance composer in the Rhine Ruhr area.

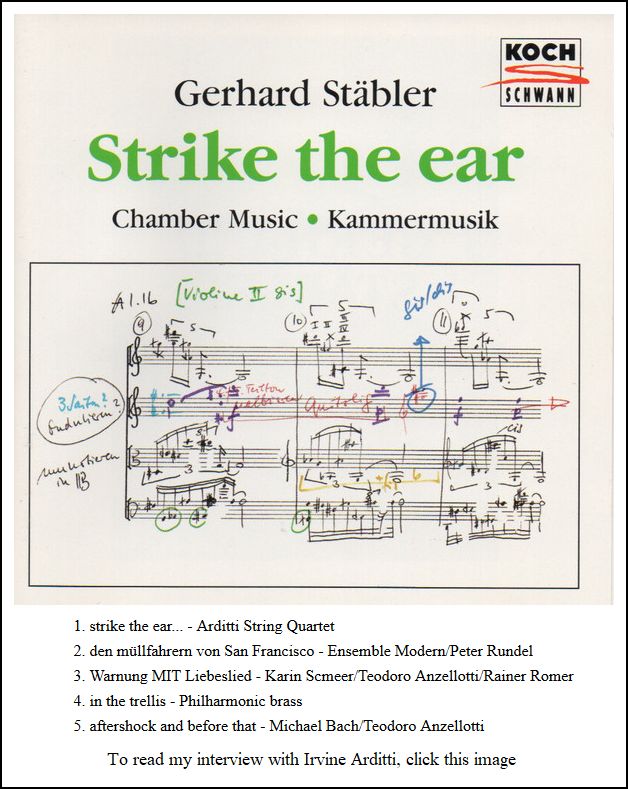

Stäbler is a renowned composer of music theatre, orchestra, chamber ensemble and solo work. Recent premieres have been with: the Borealis and Bergen International Festivals in Norway; Tanztheater Bremen for The Drift; Breslau’s ISCM World Music Days; Tokyo’s Music Documents 13; Festival Zeitgenuss and ZKM-Festival Piano Plus in Karlsruhe; Frankfurt’s HR Sinfonieorchester; Utopie Jetzt! Festival in Mülheim an der Ruhr; Theatre Ulm for Erlöst Albert E.; WDR Köln; Norske Opera Oslo for the youth opera Simon; Acht Brücken in Cologne, not to mention Dresden, the Muziekbiennale Niederrhein and Kiev.

Early in 2017, the Philharmonic Orchestra Würzburg premiered his

Concerto for Orchestra, Ausgewilderte Farben. In 2015, his music

theatre work, The Colour, after HP Lovecraft, received its

successful premiere at Mainfranken Theater Würzburg.

Early in 2017, the Philharmonic Orchestra Würzburg premiered his

Concerto for Orchestra, Ausgewilderte Farben. In 2015, his music

theatre work, The Colour, after HP Lovecraft, received its

successful premiere at Mainfranken Theater Würzburg.

In recent years, he has toured extensively as a composer, teacher and performance artist with his partner, Kunsu Shim to Iceland, Japan, Korea, Norway, Portugal, the USA and South America. In October 2017 he is invited for several weeks to lead composition masterclasses at the University of Uruguay in Montevideo.

From 2000 to 2010, he and Shim directed EarPort, the Centre for Contemporary Music in Duisburg, elaborating their original concept of “PerformanceMusik”. Since 2012, both composers have been staging the project CAGE 100 for Tonhalle Düsseldorf, a series of “PerformanceKonzerte” in various museums in Düsseldorf, as well as the series Natürlich schön!, mixing traditional with contemporary music in Schloss Benrath, Düsseldorf. In October 2015, EarPort was relaunched as a centre for experimental synergies between art forms.

Since then, interdisciplinary events have included collaborations with Schlosstheater Moers (Frequenzen-Resonanzen), GROSSE Kunstausstellung NRW at Kunstpalast Düsseldorf (Donnerhall) and the Diocese of Würzburg (the four-part project IM GEGENÜBER, with premieres for choir and orchestra, chamber music and performance art). In 2017 he will give performance concerts in Trier (opening 17), Duisburg, Essen, Bergen (Norway), Würzburg, Dresden, at the Documenta Kassel, at the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz and at Prenninger Resonanzen (Austria).

Stäbler picked up on the theme of refugee politics in his dance piece ...auf dem Weg. Eine Entdeckungsreise, which went on to win the prize for best cultural children’s and youth project in 2015 from the State of Nordrhein Westfalen, as well as THE RAFT – DAS FLOSS, based on the book The Aesthetics of Resistance by Peter Weiss.

The list of publications about Stäbler’s acclaimed work was disseminated through Paul Attinello’s notable Gerhard Stäbler. live/the opposite/daring – music, graphic, concept, event (2015).

Alongside his work as composer, Stäbler curates and organises political projects designed to transcend boundaries. He conceived the Aktive Musik-Festivals with contemporary music and when the Ruhr area hosted ISCM’s World Music Days, he became its artistic director. He is continually setting up huge music projects in public and industrial spaces, such as: RuhrWorks in New York, 1989; las jornadas de arte contemporanea in Porto, Portugal, 1993; the International Architecture Exhibition (IBA), in the Ruhr area, of 1997 and 1999; WDR Fest, Landschaftspark, Duisburg, 2008; Andriivs’kyi Descent in Kiev City Centre, 2010, and 2011 with Kunsu Shim in Vilnius and the Philharmonie in Essen.

Stäbler's decisive influence on the world of contemporary music is evidenced by many awards, including the Cornelius Cardew Memorial Prize, 1982 and the Duisburger Musikpreis, 2003. He has been awarded scholarships by the Japan Foundation, the Djerassi Foundation, California, the State of Niedersachsen and ZKM Karlsruhe. He has also been commissioned by Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik, Donaueschinger Musiktage, Musica Viva at Bavarian Radio and Festival Mouvement at Saarland Radio. He has been composer-in-residence at Three Two New York, Deutsche Oper am Rhein Düsseldorf-Duisburg, the Borealis Festival, Norway and Dias de Música Electroacústica, Portugal.

Stäbler’s music often departs from the norm,

concocting compositional elements that break through the usual performance

parameters, and so breaking down the conventional expectations of the public,

whether by gesture or movement in space, by the sensation of light or

scent, or by active interaction with the public. He’s always trying to

awaken the inner power of fantasy, sensitising all our senses to the possibility

of new, unexpected perceptions and patterns of thought. His ongoing, ever

deeper collaborations with visual artists, videographers, writers and dancers

is an essential element of his creativity.

-- From his official website

![]()

Gerhard Stäbler was born 1949 in Wilhelmsdorf, near Ravensburg in southern Germany. In 1968 he enrolled in the composition program at the Nordwestdeutsche Musikakademie in Detmold and continued his education at the Folkwang-Hochschule in Essen, where he studied with Nicolaus A. Huber (composition) and Gerd Zacher (organ). Stäbler's music often transcends the conventional framework (and therefore the audiences expectations), be it through the use of gestures or movement in space, through lighting and olfactory stimulation, or an active integration of the audience- it is very important to him to stimulate the imagination, to sensitize the ears and other perceptory organs towards unexpected perceptoral and thought processes. This is also the origin of his interest in the interaction between composition and improvisation, which feeds off of the unique tension between performers during the pre-formed yet open musical moment - as to be seen in the graphical score Red on black (1986). He was awarded the Cornelius Cardew Memorial Prize for Fürs Vaterland.

-- From another source

BD: So you’d rather write your own

music?

BD: So you’d rather write your own

music? GS: I have some ideas to start with,

but I don’t have all things at once. It comes with working on

a piece, and it needs also time for developing. It’s not a process

of improvising something. If I play music just at once, I will

get a certain kind of music which is already defined before and prepared.

But if I compose, that’s a different situation. You get some ideas,

and I do sketches, or write sketches every time where I am, and gather

thoughts about different pieces. Then I collect all these sketches

and focus them on a theme. Some are useful, and some are not useful.

Then, after collecting all these sketches, I work on the theme, and during

this process a lot of new ideas come up. Then there’s the final time

writing down the score, which, for me, is to concentrate all the collected

material.

GS: I have some ideas to start with,

but I don’t have all things at once. It comes with working on

a piece, and it needs also time for developing. It’s not a process

of improvising something. If I play music just at once, I will

get a certain kind of music which is already defined before and prepared.

But if I compose, that’s a different situation. You get some ideas,

and I do sketches, or write sketches every time where I am, and gather

thoughts about different pieces. Then I collect all these sketches

and focus them on a theme. Some are useful, and some are not useful.

Then, after collecting all these sketches, I work on the theme, and during

this process a lot of new ideas come up. Then there’s the final time

writing down the score, which, for me, is to concentrate all the collected

material. BD: So you find that the performers are really collaborators

with you?

BD: So you find that the performers are really collaborators

with you?