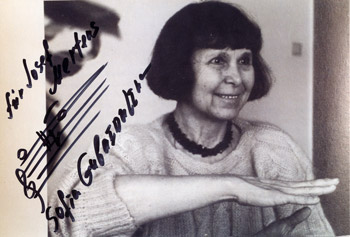

Sofia Asgatovna Gubaidulina

was born 24th October 1931 in Tschistopol, a small town on the Volga in the

Tartar Republic of the USSR. Her father was Tartar, but her mother was Russian

and Russian is her native language. When she was small, the family moved to

Kazan. She graduated from the Kazan Conservatory in 1954, before transferring

to the Moscow Conservatory, where she finished in 1961 as a post-graduate

student of Vissarion Shebalin.  In the Soviet period she earned her living writing film-scores, while reserving

part of every year for her own music. She was early attracted to the modernist

enthusiasms of her contemporaries Schnittke and Denisov but emerged with a

striking voice of her own with the chamber-orchestral Concordanza (1970).

During this period she built up a close circle of performing friends with

whom she would share long periods of improvisation and acoustic experiment.

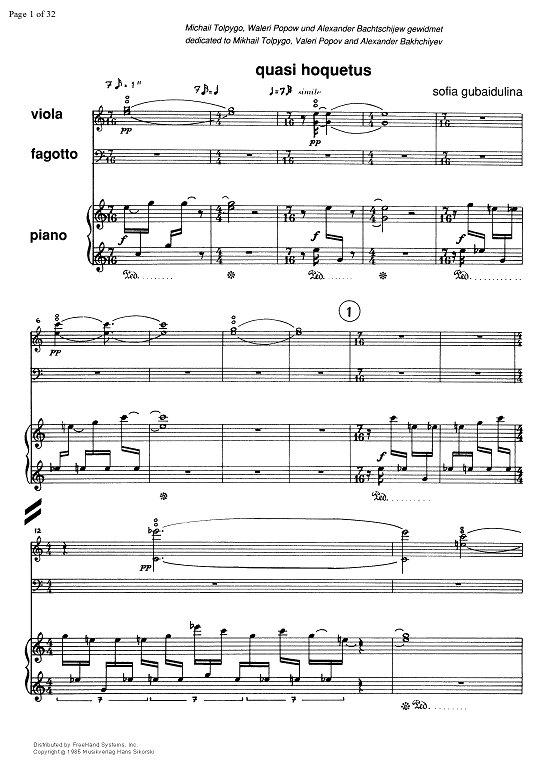

Out of these experiences came many works, such as the Concerto for bassoon

and low instruments (1975, for the bassoonist Valery Popov), The

Hour of the Soul (1976, rev.1988, for the percussionist Mark Pekarsky

with voice and orchestra) and ground-breaking pieces for the accordionist

Friedrich Lips like the frequently played De Profundis (1978).

In the Soviet period she earned her living writing film-scores, while reserving

part of every year for her own music. She was early attracted to the modernist

enthusiasms of her contemporaries Schnittke and Denisov but emerged with a

striking voice of her own with the chamber-orchestral Concordanza (1970).

During this period she built up a close circle of performing friends with

whom she would share long periods of improvisation and acoustic experiment.

Out of these experiences came many works, such as the Concerto for bassoon

and low instruments (1975, for the bassoonist Valery Popov), The

Hour of the Soul (1976, rev.1988, for the percussionist Mark Pekarsky

with voice and orchestra) and ground-breaking pieces for the accordionist

Friedrich Lips like the frequently played De Profundis (1978). From the late 1970s onwards Gubaidulina’s essentially religious temperament became more and more obvious in her work. Already in Soviet times, when the public expression of religious themes was severely repressed, she was writing pieces like the piano concerto, Introitus (1978), the violin concerto for Gidon Kremer, Offertorium (1980, rev.1986), and Seven Words for cello, accordion and string orchestra (1982, published in the USSR under the non-religious title ‘Partita’). Since the arrival of greater freedom under Gorbachev, religious themes have become her overwhelming preoccupation. Many of her religious works are on a large scale, including a cello concerto inspired by a poem about the Last Judgement (And: The feast is in full progress, 1993), Alleluia (1990), for chorus and orchestra, a concerto for cello and chorus for Mstislav Rostropovich and, most recently, the colossal Passion according to St. John (2000), a German commission to celebrate the Millennium, given its first performance by the soloists, chorus and orchestra of the Kirov Opera conducted by Valery Gergiev. Much of Gubaidulina’s more recent work also reflects her fascination with ancient principles of proportion such as the Golden Section. This is particularly clear in her chamber cantatas, Perception (1983) and Now always snow (1993) as well as in orchestral pieces like Stimmen… verstummen… (1986), Pro et Contra (1989) and Zeitgestalten (1994), this last being written for Simon Rattle and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Gubaidulina has lived in a small village outside Hamburg, Germany, where she delights in the peace and quiet she needs to fulfil the huge number of commissions she has received from all round the world. Works by Gubaidulina are represented by Boosey & Hawkes in the UK, British Commonwealth (excluding Canada) and the Republic of Ireland. [Text reprinted by kind permission

of Gerard McBurney/Boosey & Hawkes]

[Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD] ---Another biography from her North American publisher, G. Schirmer, Inc., appears at the bottom of this webpage.--- |

SG: It's very difficult question; it's very hard to choose,

but every time I have a different answer.

SG: It's very difficult question; it's very hard to choose,

but every time I have a different answer. SG: In my opinion, it's not for what, but why; it is not a

purpose but a reason. There is a deep necessity for human beings to

realize his or her unconscious.

SG: In my opinion, it's not for what, but why; it is not a

purpose but a reason. There is a deep necessity for human beings to

realize his or her unconscious. SG: This is very complicated question. Sometimes when

these thoughts occur, it can bother the composer and can limit his freedom.

A lot of limitations will be born, and from my point of view it will be on

the way of concentration during this period, and taking out from the unconscious

everything that the artist wants to transmit.

SG: This is very complicated question. Sometimes when

these thoughts occur, it can bother the composer and can limit his freedom.

A lot of limitations will be born, and from my point of view it will be on

the way of concentration during this period, and taking out from the unconscious

everything that the artist wants to transmit. SG: Of course.

SG: Of course.| Sofia

Gubaidulina was born in Chistopol in the Tatar Republic of the Soviet

Union in 1931. After instruction in piano and composition at the Kazan Conservatory,

she studied composition with Nikolai Peiko at the Moscow Conservatory, pursuing

graduate studies there under Vissarion Shebalin. Until 1992, she lived in

Moscow. Since then, she has made her primary residence in Germany, outside

Hamburg.

|

This interview was recorded in Chicago on April 18, 1997. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 2001, on WNUR in 2005, and on

Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005, 2006 and 2008. This

transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.