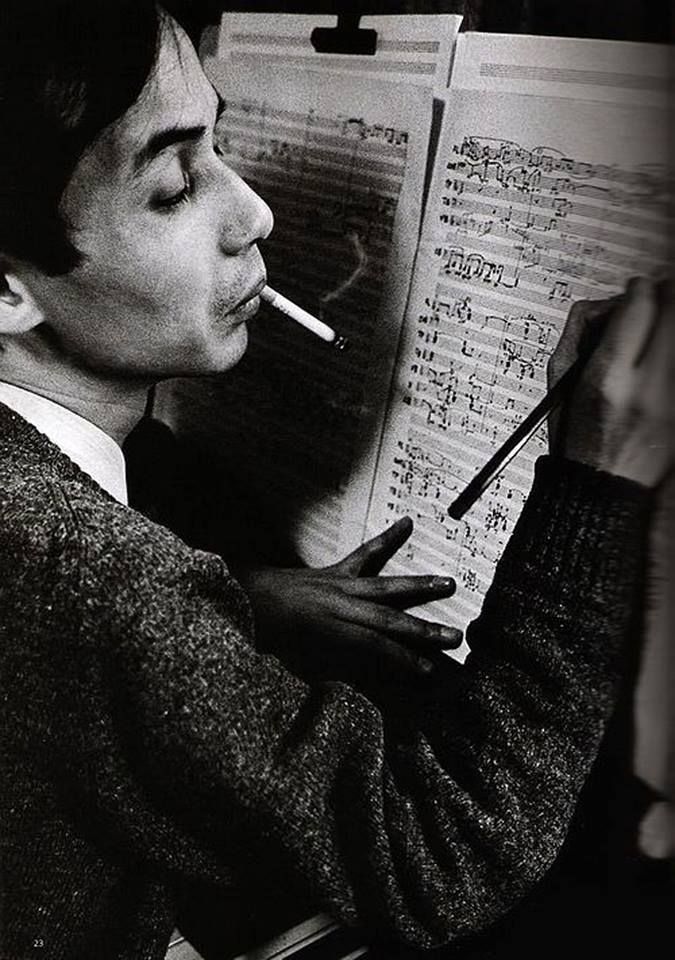

Tōru Takemitsu (武満 徹) was born

in Tokyo on October 8, 1930. He began attending the Keika Junior High School

in 1943 and resolved to become a composer at the age of sixteen.

Tōru Takemitsu (武満 徹) was born

in Tokyo on October 8, 1930. He began attending the Keika Junior High School

in 1943 and resolved to become a composer at the age of sixteen.

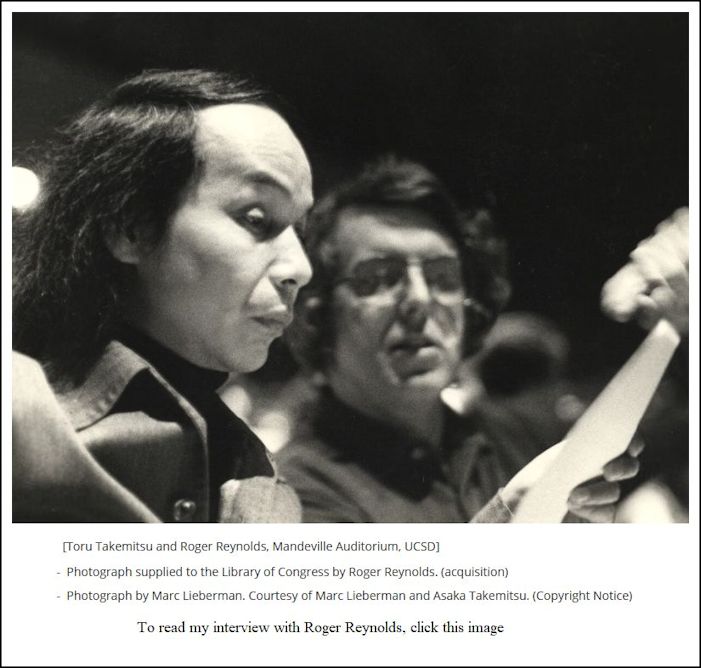

During the post-war years, he came into contact with Western music through radio broadcasts by the American occupying forces – not only jazz, but especially classical music by Debussy and Copland and even by Schoenberg. He made his debut at the age of twenty with a piano piece Lento in Due Movimenti. Although Takemitsu was essentially a self-taught composer, he nevertheless sought contact with outstanding teachers: Toshi Ichiyanagi acquainted the composer with the European avant-garde of Messiaen, Nono, and Stockhausen (shown together in photo at right), and Fumio Hayasaka introduced Takemitsu to the world of film music and forged contacts to the film director Akira Kurosawa for whom Takemitsu produced several scores to film plots. Alongside his musical studies, Takemitsu also took a great interest in other art forms including modern painting, theatre, film and literature (especially lyric poetry). His cultural-philosophical knowledge was acquired through a lively exchange of ideas with Yasuji Kiyose paired with his own personal experiences. In 1951, the group “Experimental Workshop” was co-founded by Takemitsu, other composers and representatives from a variety of artistic fields; this was a mixed media group whose avant-garde multimedia activities soon caused a sensation. Takemitsu taught composition at Yale University and received numerous invitations for visiting professorships from universities in the USA, Canada and Australia. He died in Tokyo on February 20, 1996. |

BD: You let your ideas be molded by the possibilities

of our orchestra?

BD: You let your ideas be molded by the possibilities

of our orchestra? BD: Are you pleased with what you have come up with

in your music?

BD: Are you pleased with what you have come up with

in your music? BD: So, rather than advise them,

you learn from them?

BD: So, rather than advise them,

you learn from them?| Toward the Sea (海へ, Umi

e) is a work by the Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu, commissioned

by Greenpeace for the Save the Whales campaign.

Each version lasts around eleven minutes. There are numerous recordings of each version. The work is divided into three sections—The Night, Moby-Dick, and Cape Cod. These titles are in reference to Melville's novel Moby Dick, or The Whale. The composer wished to emphasize the spiritual dimension of the book, quoting the passage, "meditation and water are wedded together". He also said that, "The music is a homage to the sea which creates all things and a sketch for the sea of tonality"; Toward the Sea was written at a time when Takemitsu was increasingly returning to tonality after a period of experimental composition. Most of the work is written in free time, with no bar lines (except

in the second version, to facilitate conducting). In each version, the

flute has the primary melodic line, based in part on a motif spelling "sea"

in German musical notation: E♭–E–A (S-E-A) shown above. This motif reappeared

in several of Takemitsu's later works. |

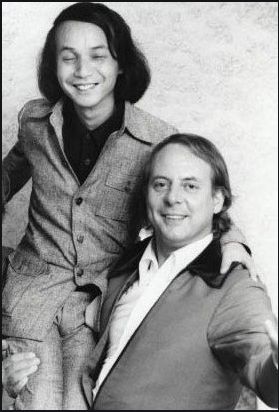

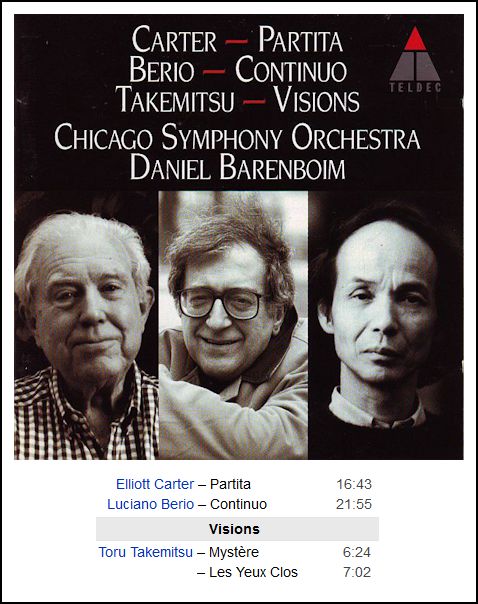

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 6, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that day, and again in October of 1990, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.