By Bruce Duffie

BD: How is the audience

in Arizona different from that in New York City

or San Francisco or Milan?

BD: How is the audience

in Arizona different from that in New York City

or San Francisco or Milan? GT: Yes, with Leonie

Rysanek and George London. [See my Interview with Leonie

Rysanek.] I performed

that role with them many, many times, and every time it was exciting

for me because they were exciting. Those two had electrifying

voices and great

personalities, and the audiences would go out of their minds over their

performances. It was wonderful to be part of an ensemble like

that. I enjoyed the role very much. Some people say he’s a

venal old man who’s trying to make a few bucks off his daughter, but

they forget that what he was a product of his age. In those

days, people wanted to see to it that they could make a good marriage

for their daughters, and at the same time enhance their own financial

position. And Daland doesn’t have to be that old. Operatic

fathers are stereotyped into looking like grandfathers. If

Senta is 18 years old, Daland can be 38 or 40. They married young

in those days. It’s wrong to make every father look like the

Ancient Mariner. But he thinks he’s working out a nice

arrangement for his daughter, and he’s looking to get his hands on some

of the wealth that’s in the hold of the Dutchman’s ship.

GT: Yes, with Leonie

Rysanek and George London. [See my Interview with Leonie

Rysanek.] I performed

that role with them many, many times, and every time it was exciting

for me because they were exciting. Those two had electrifying

voices and great

personalities, and the audiences would go out of their minds over their

performances. It was wonderful to be part of an ensemble like

that. I enjoyed the role very much. Some people say he’s a

venal old man who’s trying to make a few bucks off his daughter, but

they forget that what he was a product of his age. In those

days, people wanted to see to it that they could make a good marriage

for their daughters, and at the same time enhance their own financial

position. And Daland doesn’t have to be that old. Operatic

fathers are stereotyped into looking like grandfathers. If

Senta is 18 years old, Daland can be 38 or 40. They married young

in those days. It’s wrong to make every father look like the

Ancient Mariner. But he thinks he’s working out a nice

arrangement for his daughter, and he’s looking to get his hands on some

of the wealth that’s in the hold of the Dutchman’s ship. BD: So he got you to do

the right thing for the wrong reason!

BD: So he got you to do

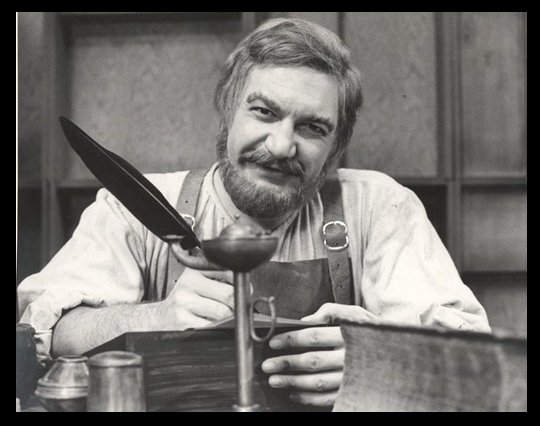

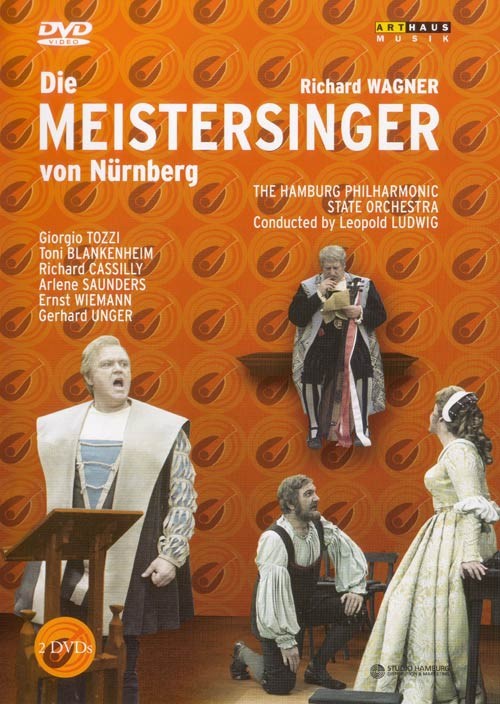

the right thing for the wrong reason! GT: That’s right, with

the Hamburg Staatsoper. I was very

flattered at that because I had made my debut in Germany as Hans Sachs,

having flown in from the Colón in Buenos Aires. I had no

rehearsal really. I just went through the part with the conductor

at

the piano, and the assistant stage-director brought blueprints and

showed me where everything was and pointed out where I came in and

where I went. That was my rehearsal and I made my debut.

Thank God it went very well, very beautifully. I mean that – He

must have decided to be with me. The cast was wonderful and the

very next day, Rolf Liebermann asked me to do the film. He told

me that he’d had every singer who does the role perform it on the stage

for him before deciding, and he wanted me to do it. I was very,

very flattered and thrilled and excited. I couldn’t believe

it. I still didn’t speak the

language, but Liebermann said he understood about 94% of everything I

had sung. I did work very hard at it. I wore out four

coaches learning the part! I learned to think idiomatically in

German, and while I was there I rented a television and watched

German plays to see how the physical language, the body language,

worked. So it was exciting to do.

GT: That’s right, with

the Hamburg Staatsoper. I was very

flattered at that because I had made my debut in Germany as Hans Sachs,

having flown in from the Colón in Buenos Aires. I had no

rehearsal really. I just went through the part with the conductor

at

the piano, and the assistant stage-director brought blueprints and

showed me where everything was and pointed out where I came in and

where I went. That was my rehearsal and I made my debut.

Thank God it went very well, very beautifully. I mean that – He

must have decided to be with me. The cast was wonderful and the

very next day, Rolf Liebermann asked me to do the film. He told

me that he’d had every singer who does the role perform it on the stage

for him before deciding, and he wanted me to do it. I was very,

very flattered and thrilled and excited. I couldn’t believe

it. I still didn’t speak the

language, but Liebermann said he understood about 94% of everything I

had sung. I did work very hard at it. I wore out four

coaches learning the part! I learned to think idiomatically in

German, and while I was there I rented a television and watched

German plays to see how the physical language, the body language,

worked. So it was exciting to do. |

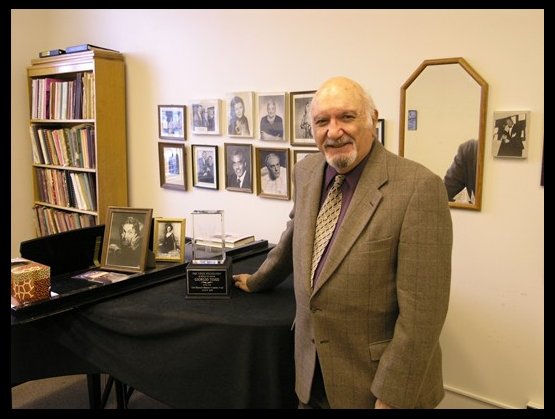

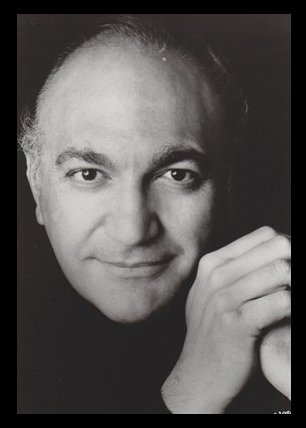

Giorgio Tozzi, Esteemed Bass at the Met, Is

Dead at 88

By MARGALIT FOX Published June 2, 2011 The New York Times [with slight corrections, and the addition of links] Giorgio Tozzi, a distinguished bass who spent two decades with the Metropolitan Opera and also appeared on film, television and Broadway, died on Monday in Bloomington, Ind. He was 88. The cause was a heart attack, his son, Eric, said. At his death, Mr. Tozzi (pronounced TOT-zee) was a distinguished professor emeritus at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, where he had taught since 1991. He was previously on the Juilliard School faculty. Esteemed for his warm, smooth voice; skillful acting; pinpoint diction; and authoritative stage presence — he was 6 foot 2 in his prime — Mr. Tozzi sang 528 performances with the Met. He was so ubiquitous there for so long that The New York Times was later moved to describe him (admiringly) as “inescapable.” Mr. Tozzi made his Met debut as Alvise in “La Gioconda,” by Amilcare Ponchielli, in 1955. Reviewing the performance, The New York Post wrote that he “proved to have a voice of beautiful quality,” adding, “It was rich in texture and expertly handled both as to characterization and technique.” His most famous performances at the Met include the title roles in Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov” and Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro”; Ramfis in Verdi’s “Aïda”; Don Basilio in Rossini’s “Barber of Seville”; Philip II in Verdi’s “Don Carlo”; and Hans Sachs in Wagner’s “Meistersinger von Nürnberg.” He originated the role of the Doctor in Samuel Barber’s “Vanessa,” which had its world premiere at the Met in 1958. Conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos, the production also starred Eleanor Steber and Nicolai Gedda. Mr. Tozzi’s last performance with the Met was in 1975, as Colline in Puccini’s “La Bohème.” He also sang with the San Francisco Opera, La Scala and other companies and appeared as a soloist with major symphony orchestras throughout the United States and Europe. On film Mr. Tozzi dubbed the singing voice of the actor Rossano Brazzi in the role of Emile de Becque in “South Pacific” (1958), directed by Joshua Logan. (Mr. Tozzi had played the role himself, opposite Mary Martin, in a West Coast production of the musical the year before.) On the small screen he sang King Melchior in the 1978 television film of Gian Carlo Menotti’s “Amahl and the Night Visitors,” also starring Teresa Stratas. [See Bruce Duffie’s Interviews with Gian Carlo Menotti.] On Broadway he received a Tony nomination for the role of the lonely California grape farmer Tony Esposito in the 1979 revival of Frank Loesser’s operatic musical comedy “The Most Happy Fella.” (The award went to Jim Dale for “Barnum.”) Mr. Tozzi was sometimes asked from what part of Italy he hailed. The answer was Chicago, where he was born George John Tozzi on Jan. 8, 1923. He began singing as a teenager but entered DePaul University planning to major in biology. He soon returned to music, studying with Rosa Raisa, Giacomo Rimini and John Daggett Howell. After Army service in World War II Mr. Tozzi began his vocal life as a baritone. He made his debut (as George Tozzi) in 1948, singing Tarquinius in Benjamin Britten’s opera “The Rape of Lucretia.” Staged at the Ziegfeld Theater on Broadway, the production also starred Kitty Carlisle. Mr. Tozzi later moved to Milan for vocal study with Giulio Lorandi, an experience that cost him — literally — the shirt off his back. Money from the G.I. Bill earmarked for his lessons was delayed for nine months. First, Mr. Tozzi pawned his cameras. Then he pawned his suitcases. Finally, he pawned his clothes. The act was prophetic. In his many outings as Colline, the threadbare philosopher in “La Bohème,” Mr. Tozzi would sing “Vecchia Zimarra,” an aria about pawning his coat. Mr. Tozzi emerged from Milan a bass. Soon afterward, at the suggestion of RCA Victor, for whom he made some of his early recordings, he became Giorgio Tozzi, with its fittingly operatic overtones. As an actor Mr. Tozzi had guest roles on several television series of the 1970s and ’80s, including “The Odd Couple,” “Baretta,” “Kojak” and “Knight Rider.” Mr. Tozzi’s first wife, the former Catherine Dieringer, a singer, died in 1963. His survivors include his wife, Monte Amundsen, also a singer, whom he married in 1967; their children, Eric Tozzi and Jennifer Tozzi Hauser; and three grandchildren. He received three Grammy Awards, for a “Figaro,” released in 1959, and a “Turandot” (1960), both conducted by Erich Leinsdorf, and an “Aïda” (1962) conducted by Georg Solti. [See Bruce Duffie’s Interviews with Erich Leinsdorf, and his Interviews with Sir Georg Solti.] In an interview with The Times in 1961, Mr. Tozzi waxed philosophical about the peculiar onus of being an operatic bass. “We have to sing short roles as well as long ones, unlike other leading singers,” he said. “I don’t mind short roles — they can be challenging. But sing them once, and someone says to you: ‘You were great! When are you going to sing a big role?’ ” |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on January 17,

1988. Portions

(along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1993 and 1998. The

transcript was published in Wagner

News in March, 1988. It was re-edited, photos and links

were added, and it was posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.