|

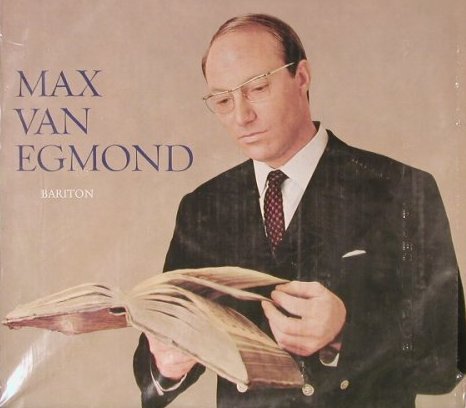

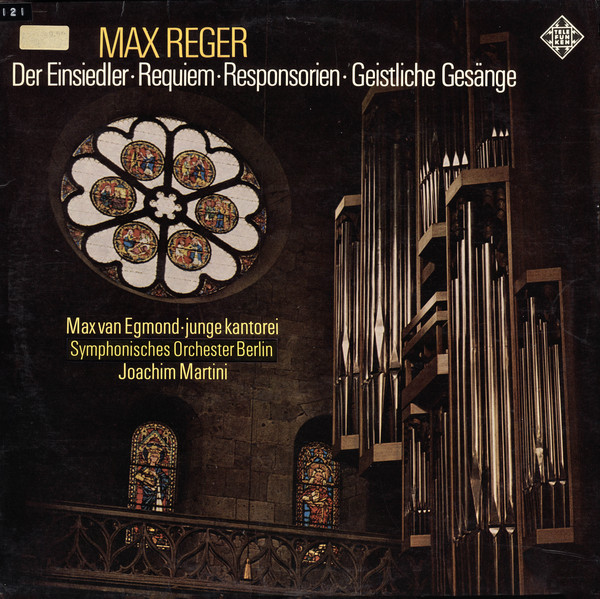

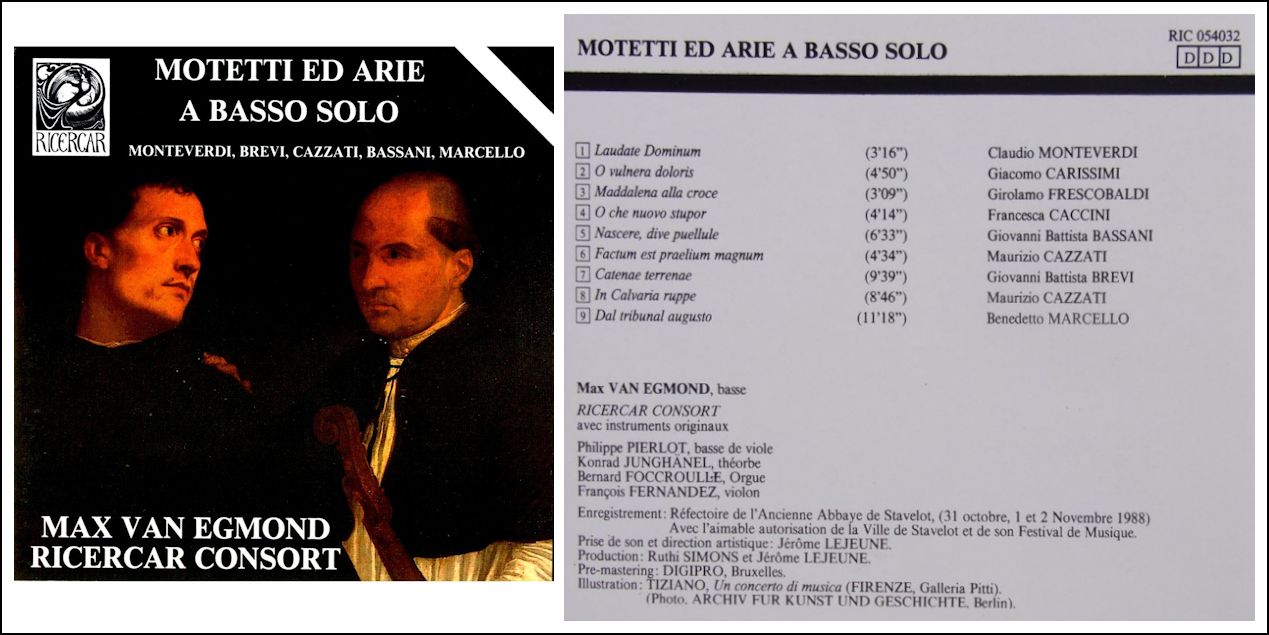

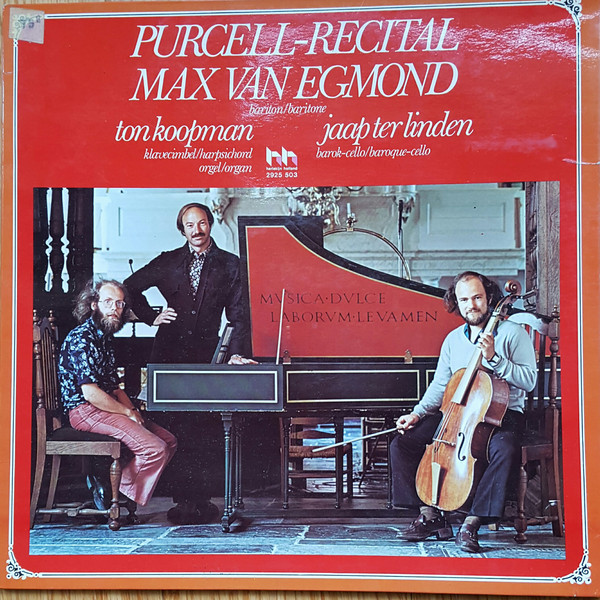

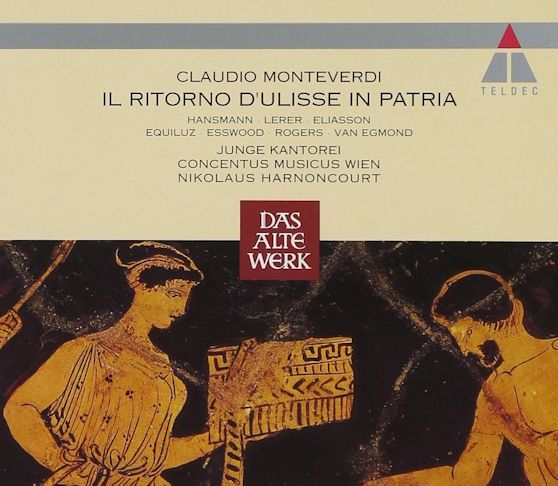

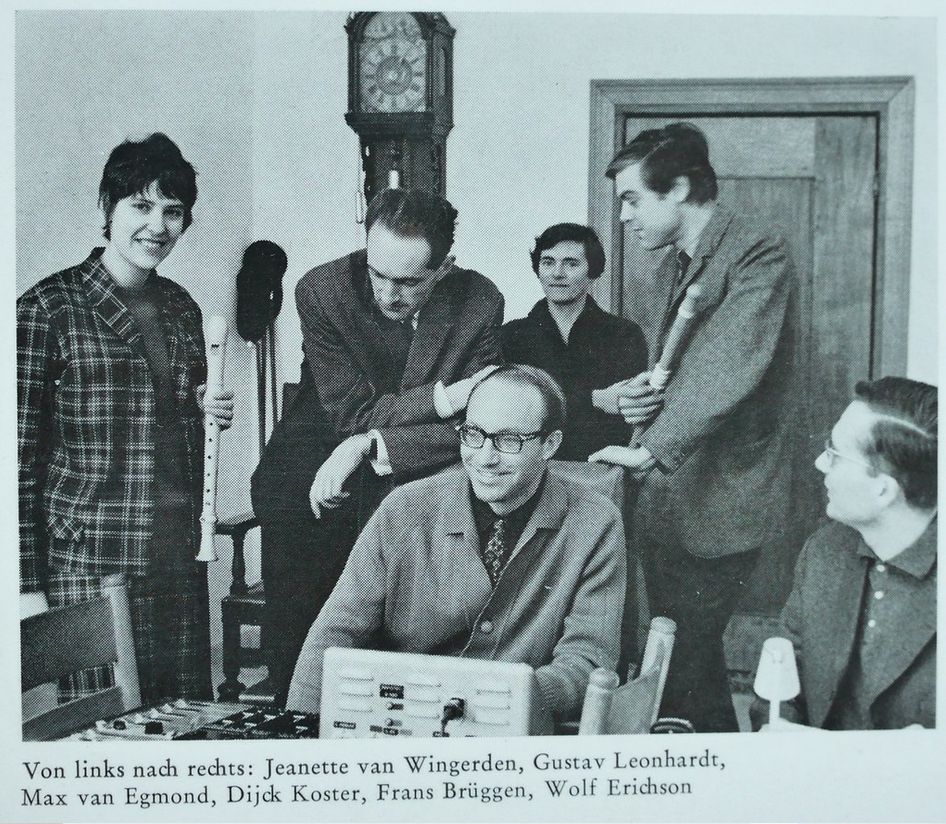

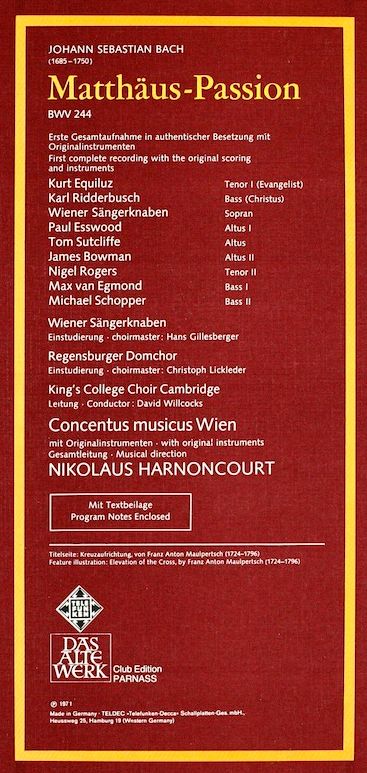

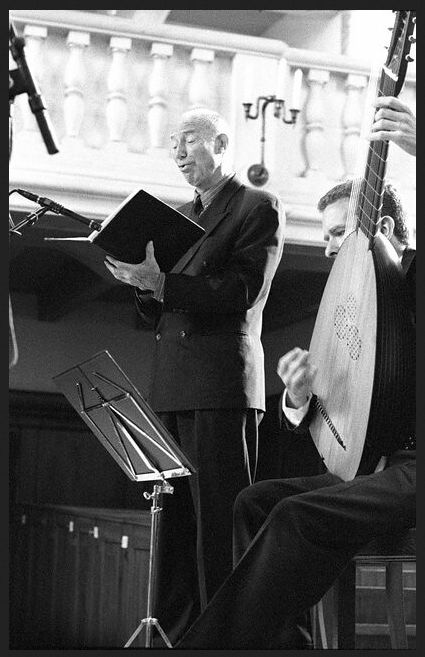

Max van Egmond (born February 1, 1936 in Semarang, Java, Indonesia [the former Dutch East Indies]) is a Dutch bass and baritone singer. He has focused on oratorio and Lied, and is known for singing works of Johann Sebastian Bach. He was one of the pioneers of historically informed performance of Baroque and Renaissance music. He studied voice at Hilversum with Tine van Willingen de Lorme. At the age of eighteen he became a member of De Nederlandse Bachvereniging (Netherlands Bach Society). Starting in 1965, he became involved in the complete Bach recordings of Gustav Leonhardt, Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Frans Brüggen. He recorded the St Matthew Passion under Claudio Abbado in 1969 and Nikolaus Harnoncourt in 1970, singing the bass arias. In 1973, he was the Vox Christi in the first historically informed performance in the Netherlands of Bach's St Matthew Passion. Johan van der Meer conducted the Groningse Bachvereniging. Ton Koopman and Bob van Asperen played the organs. In 1977, he performed the part with Charles de Wolff and De Nederlandse Bachvereniging, in 1989 with Gustav Leonhardt. In the St John Passion he recorded the words of Jesus in 1965 with Harnoncourt and the Concentus Musicus Wien, in 1979 with van der Meer, in 1986 with de Wolff, and in 1987 the arias with Sigiswald Kuijken and La Petite Bande. He participated in recordings of Monteverdi's operas with Harnoncourt,

L'Orfeo in 1968, and the first complete recording of Il

ritorno d'Ulisse in patria in 1971. He also performed more recent

operas, such as the world premieres at De Nederlandse Opera of Jurriaan

Andriessen's Het Zwarte Blondje in 1962, and of Antony Hopkins'

Three's Company in 1963. In 1969 he was the soloist in Reger's

Hebbel Requiem in concerts recorded live in the Berliner

Philharmonie with Junge Kantorei, Symphonisches Orchester Berlin and

conductor Joachim Carlos Martini. In 1976 he performed with the same

choir Handel's Messiah in Eberbach Abbey.

He was a teacher at the Sweelinck Conservatory Amsterdam from 1980 until 1995, and conducted master classes annually in Mateus, Portugal, and at the Baroque Performance Institute at Oberlin, Ohio since 1978. |

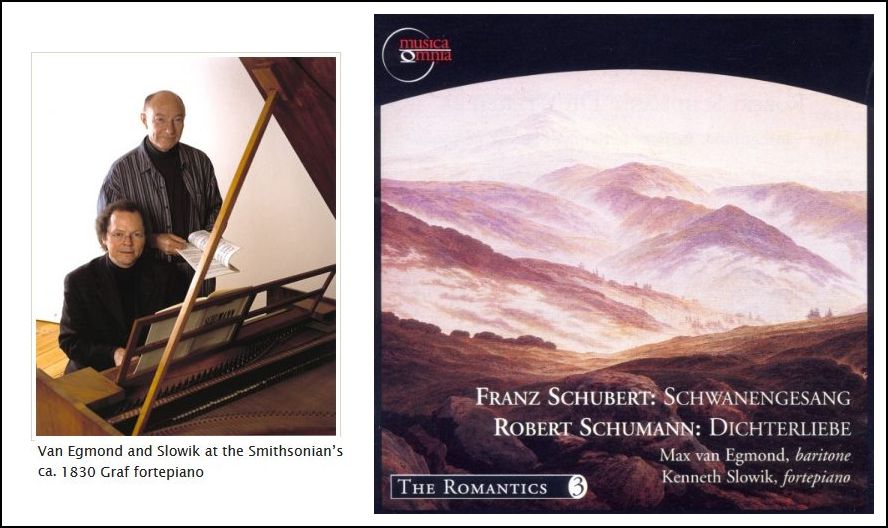

van Egmond: No! Just as I said,

I depart from the universal skills that a singer should have, and it

is just the style. What you do with the voice differs a bit.

In dramatic music, for instance, I find myself doing more with the romantic

rubatos. Sometimes there is a little more vibrato in the voice,

and the extremes in volume are bigger. I did a romantic Liederabend

[song recital] three days ago in Houston, and the program had some

Haydn, some Fauré, and a lot of Schubert, plus some works by

a contemporary Dutch composer, Alexander Voolmolen. As I said,

one tries to be very dramatic in Romantic music, and this means that you

give more expansion to the voice. But it’s not an entirely different

way of singing.

van Egmond: No! Just as I said,

I depart from the universal skills that a singer should have, and it

is just the style. What you do with the voice differs a bit.

In dramatic music, for instance, I find myself doing more with the romantic

rubatos. Sometimes there is a little more vibrato in the voice,

and the extremes in volume are bigger. I did a romantic Liederabend

[song recital] three days ago in Houston, and the program had some

Haydn, some Fauré, and a lot of Schubert, plus some works by

a contemporary Dutch composer, Alexander Voolmolen. As I said,

one tries to be very dramatic in Romantic music, and this means that you

give more expansion to the voice. But it’s not an entirely different

way of singing.

van Egmond: Yes, but not as frequently as the

concerts.

van Egmond: Yes, but not as frequently as the

concerts.

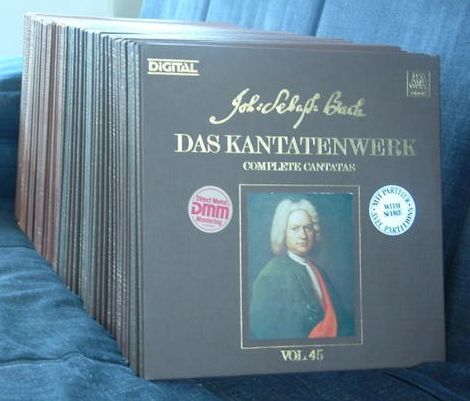

van Egmond: [Laughs] It’s part

of the job, and the projects that I’m involved in are very interesting

and very important. I have done quite a few solo recitals, both

with Romantic and Baroque music, but what is getting most of the recognition

is the project of the complete Bach Church Cantatas, recorded on Teldec

or Telefunken. That is such a rewarding and interesting thing that

I’m very glad I’m in it. We are approaching the finale of it.

This coming January we will have the last recording session. Then

they will all have been recorded, and maybe after half a year the last

box will be released. It has been a work of around twenty years, and

I’m very privileged to have joined the project from the very start until

the end.

van Egmond: [Laughs] It’s part

of the job, and the projects that I’m involved in are very interesting

and very important. I have done quite a few solo recitals, both

with Romantic and Baroque music, but what is getting most of the recognition

is the project of the complete Bach Church Cantatas, recorded on Teldec

or Telefunken. That is such a rewarding and interesting thing that

I’m very glad I’m in it. We are approaching the finale of it.

This coming January we will have the last recording session. Then

they will all have been recorded, and maybe after half a year the last

box will be released. It has been a work of around twenty years, and

I’m very privileged to have joined the project from the very start until

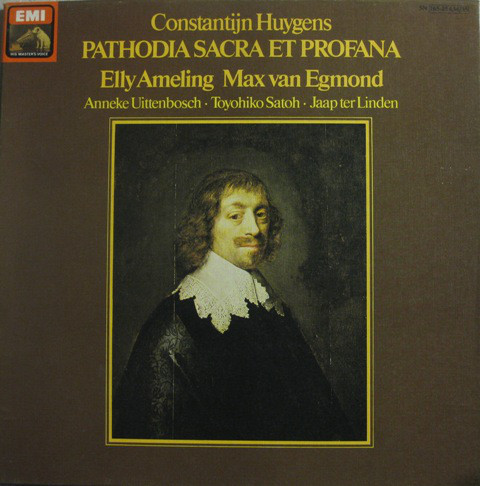

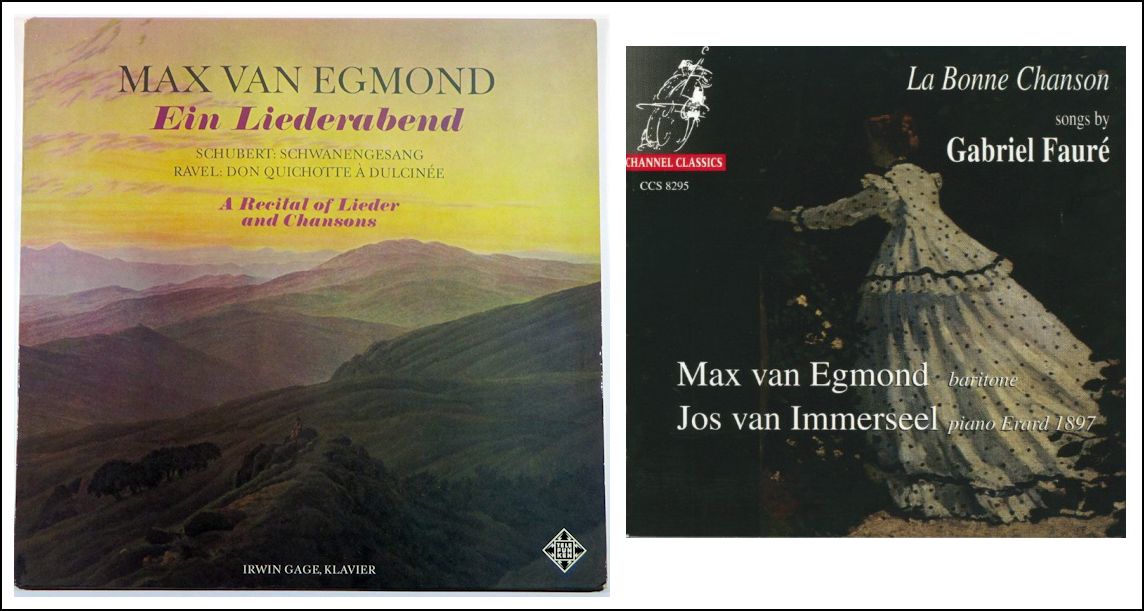

the end. BD: But he clothed it in Twentieth

Century harmony? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right,

see my interviews with Judith Nelson, and

William Christie.]

BD: But he clothed it in Twentieth

Century harmony? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right,

see my interviews with Judith Nelson, and

William Christie.] BD: Do you sing differently in different

sized halls, when you sing in a small hall or a large hall?

BD: Do you sing differently in different

sized halls, when you sing in a small hall or a large hall? BD: Who are the great Dutch composers

coming along?

BD: Who are the great Dutch composers

coming along? BD: [Surprised] Really???

BD: [Surprised] Really???

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 7, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.