Sir Constantijn Huygens (4 September

1596 – 28 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was secretary

to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father

of the scientist Christiaan Huygens.

Constantijn Huygens was born in The Hague, the second son of Christiaan Huygens

(senior), secretary of the Council of State, and Susanna Hoefnagel, niece

of the Antwerp painter Joris Hoefnagel.

Constantijn was a gifted child in his youth. His brother Maurits and he were

educated partly by their father and partly by carefully instructed governors.

When he was five years old, Constantijn and his brother received their first

musical education.

They started with singing lessons, and they learned their notes using gold

colored buttons on their jackets. It is striking that Christiaan senior imparted

the 'modern' system of 7 note names to the boys, instead of the traditional,

but much more complicated hexachord system. Two years later the first lessons

on the viol started, followed by the lute and the harpsichord. Constantijn

showed a particular acumen for the lute. At the age of eleven he was already

asked to play for ensembles, and later — during his diplomatic travels —

his lute playing was in demand. He was asked to play at the Danish Court

and for James I of England, although they were not known for their musical

abilities.

The boys were also schooled in art through their parents art collection,

and also their connection to the magnificent collection of paintings in the

Antwerp house of diamond and jewelry dealer, Gaspar Duarte (1584–1653), who

was a Portuguese Jewish exile.

Constantijn also had a talent for languages. He learned French, Latin and

Greek, and at a later age Italian and English. He learned by practice, the

modern way of learning techniques. Constantijn received education in math,

law and logic, and he learned how to handle a pike and a musket.

In 1614 Constantijn wrote his first Dutch poem, inspired by the French poet

Guillaume de Salluste Du Bartas, in which he praises rural life. In his early

20s, he fell in love with Dorothea, however their relationship did not last

and Dorothea met someone else. In 1616, Maurits and Constantijn started studies

at Leiden University. Studying in Leiden was primarily seen as a way to build

a social network. Shortly after, Maurits was called home to assist his father.

Constantijn finished his studies in 1617 and returned home. This was followed

by six weeks of training with Antonis de Hubert, a lawyer in Zierikzee.

In the Spring of 1618 Constantijn found employment with Sir Dudley Carleton,

the English envoy at the Court in The Hague. In the summer, he stayed in

London in the house of the Dutch ambassador, Noël de Caron. During his

time in London his social circle widened and he also learned to speak English.

In 1620, towards the end of the Twelve Years' Truce, he travelled as a secretary

of ambassador François van Aerssen to Venice, to gain support against

the threat of renewed war. He was the only member of the legation who could

speak Italian. In January 1621 he traveled to England as the secretary of

six envoys of the United Provinces with the object of persuading James I

to support the German Protestant Union, returning in April of that year.

In December 1621 he left with another delegation, this time with the aim of

requesting support for the United Provinces, returning after a year and two

months in February 1623. There was yet another trip to England in 1624.

He is often considered a member of what is known as the Muiderkring, a group of leading intellectuals

gathered around the poet Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft, who met regularly at

the castle of Muiden near Amsterdam. In 1619 Constantijn came into contact

with Anna Roemers Visscher and with Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft. Huygens exchanged

many poems with Anna. In 1621 a poetic exchange with Hooft also starts. Both

would always try to exceed the other.

In 1622, when Constantijn stayed as a diplomat for more than one year in

England, he was knighted by King James I. This marked the end of Constantijn's

formative years. Huygens was employed as a secretary to Frederick Henry,

Prince of Orange, who — after the death of Maurits of Orange — was appointed

as stadtholder. In 1626 Constantijn fell in love with Suzanna van Baerle.

Earlier courtship by the Huygens family to win her for Maurits had failed.

Constantijn wrote several sonnets for her, in which he calls her Sterre (Star).

They wed on 6 April 1627.

The couple had five children: in 1628 their first son, Constantijn Jr., in

1629 Christiaan, in 1631 Lodewijk and in 1633 Philips. In 1637 their daughter

Suzanna was born; shortly after her birth their mother died.

Huygens started a successful career despite his grief over the death of his

wife (in 1638). In 1630 he was appointed to the Council and Exchequer, managing

the estate of the Orange family. This job provided him with an income of

about 1000 florins a year. In that same year he bought the estate Zuilichem

and became known as Lord of Zuilichem. In 1632 Louis XIII of France, the

protector of the famous exiled jurist Hugo Grotius, appointed him as knight

in the Order of Saint-Michel. In 1643 Huygens was granted the honor of displaying

a golden lily on a blue field in his coat of arms.

In 1634 Huygens received from Prince Frederick Henry a piece of property

in The Hague on the north side of the Binnenhof. The land was near the property

of a good friend of Huygens, Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen, who built

his house, the Mauritshuis, around the same time and using the same architect,

Huygens' friend Jacob van Campen.

At the start of the 1630s he was also in touch with René Descartes,

with Rembrandt, and the painter Jan Lievens. He became friends with John

Donne, and translated his poems into Dutch. He was unable to write poetry

for months because of his anguish over his wife's death, but eventually he

composed, inspired by Petrarch, the sonnet Op de dood van Sterre (On the death of

Sterre), which was well received.

After a couple of years as a widower, Huygens bought a piece of land in Voorburg

and commissioned the building of Hofwijck, which was inaugurated in 1642

in the company of friends and relatives. Here Huygens hoped to escape the

stress at court in The Hague, forming his own 'court', indicated by the name

of the house which has a double meaning: Hof (=Court or courtyard) Wijck

(=avoid or township). In that same year, his brother Maurits died. Due to

his grief Huygens wrote little Dutch poetry, but he continued to write epigrams

in Latin. Shortly afterwards, he began writing Dutch pun poems, which are

very playful by nature. In 1644 and 1645 Huygens began more serious work.

As a new year's present for Leonore Hellemans, he composed the Heilige Daghen, a series of sonnets on

the Christian holidays. In 1647 he published another work, in which play

and seriousness are united, Ooghentroost,

addressed to Lucretia of Trello, who was losing her sight and who was already

half-blind. The poem was offered as consolation.

From 1650 to 1652 Huygens wrote the poem Hofwijck in which he described the

joys of living outside the city. It is thought that Huygens wrote his poetry

as a testament to himself, a memento mori,

because Huygens lost so many dear friends and family during this time: Hooft

(1647), Barlaeus (1648), Maria Tesschelschade (1649) and Descartes (1650).

In 1645, his sons Constantijn Jr. and Christiaan began their studies in Leiden.

In these years Prince Frederick Henry of Orange, Huygens' confidante and

protector, became increasingly ill, and died in 1647. The new stadtholder,

William II of Orange, greatly appreciated Huygens and gave him the estate

of Zeelhem, but he died too in 1650.

The emphasis of Huygens' activities moved more and more to his presidency

of the Council of the house of Orange, which was in the hands of the young

Prince inheritor, a small baby. He traveled frequently during that time,

in connection with his work. There were however strong disagreements between

the baby's widowed mother in law Amalia van Solms, and widow daughter in

law Mary, Princess Royal, (4 November 1631 – 24 December 1660, aged 29) on

even the name for christening the Dutch-English Royal newborn.

In 1657, his son Philips died after a short sickness during his Grand Tour

while in Prussia. In that same year Huygens became seriously ill, but healed

in a miraculous manner.

In 1680 Constantijn Jr. moved with his family out of the house of his father.

To stop the gossiping which started shortly afterwards, Huygens write the

poem Cluijs-werck, in which he shows

a glimpse of the latter stages of his life.

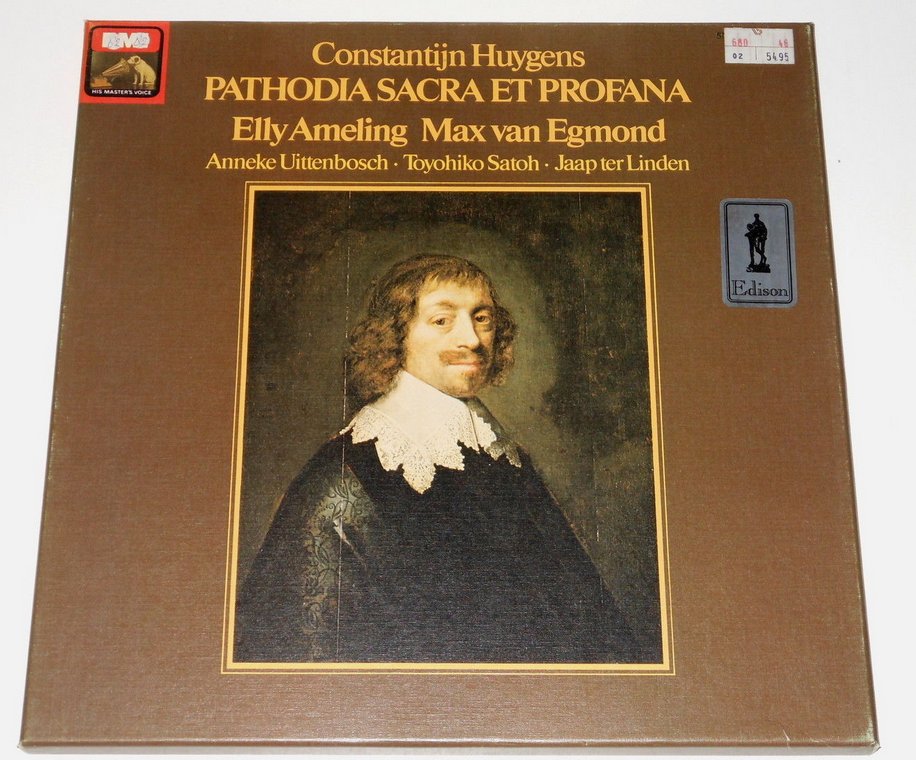

He still tried to find time to publish more of his work. In 1647 a number

of Huygens' musical creations, Pathodia

sacra et profana, was published in Paris. It contained some compositions

in Latin on the words of psalms in French, and Italian amorous worldly texts.

The work was dedicated to the pretty niece, Utricia Ogle, of an English diplomat.

In 1648 Huygens wrote Twee ongepaerde

handen for a harpsichord. This work was connected with Marietje Casembroot,

a twenty-five-year-old harpsichord player, with whom he could share his love

for music.

As he was older now, Huygens found refuge in music. He wrote around 769 compositions

during his lifetime.

Constantijn Huygens died in The Hague on Good Friday, 28 March 1687 at the

age of 90. A week later he was buried in the Grote Kerk in the Hague, together

with his son, the famous scientist Christiaan Huygens.

In 1947 a literary award was created, the Constantijn Huygens Award, to honor

his legacy

|

BD

BD

EA

EA BD

BD EA

EA BD

BD BD

BD