|

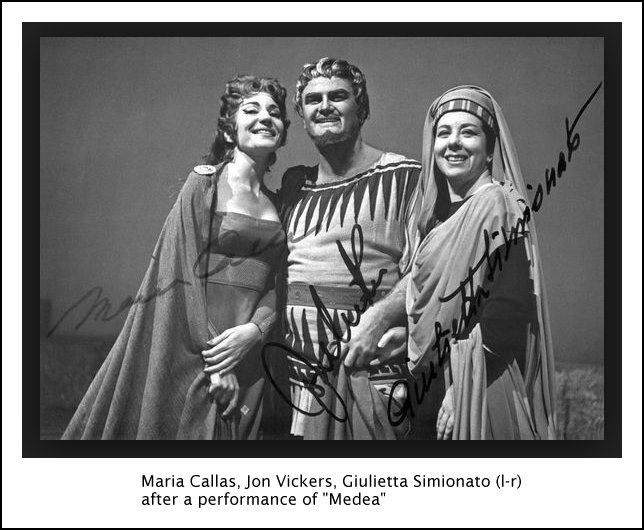

Bruce Duffie: To make it seamless? Jon Vickers: Yes, seamless. I have caught that period of history, but it is coming to an end. The greatest example of it that I ever knew in all my operatic experience was Giulietta Simionato. I think she had the most supreme seamless voice from the bottom to the top I have ever heard, and it was a joy always to sing with her. I used to tell her, "Giulietta, I love to sing with you because all night I take vocal lessons."

|

Bruce Duffie:

First, what is the secret of singing the smooth bel canto line?

Bruce Duffie:

First, what is the secret of singing the smooth bel canto line? BD: Were the

composers correct in placing the male characters in the mezzo-soprano range?

BD: Were the

composers correct in placing the male characters in the mezzo-soprano range?Giulietta Simionato at Lyric Opera of

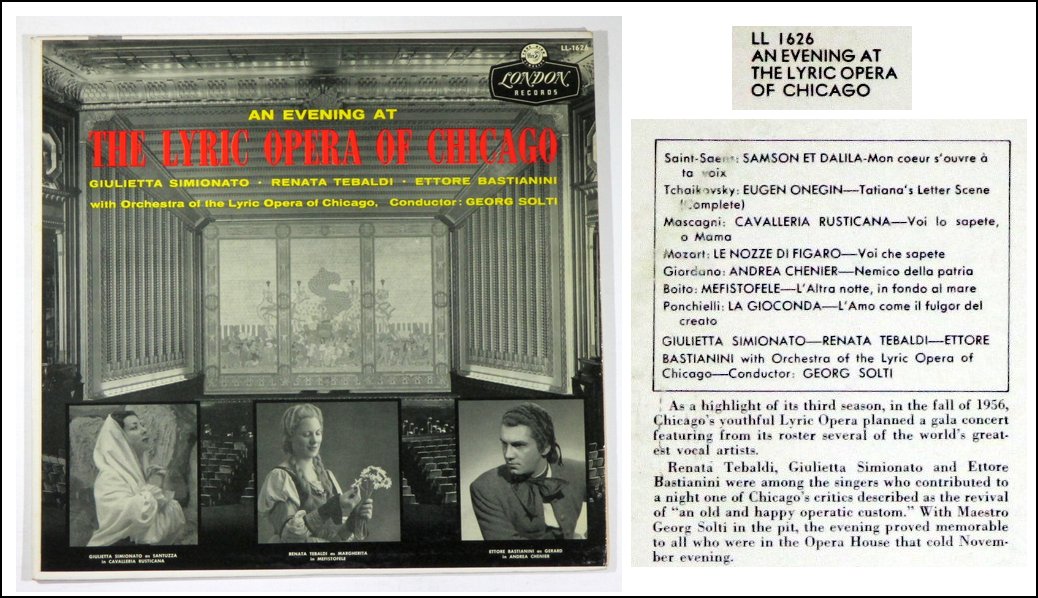

Chicago

1954 - [Opening Night] Norma (Adalgisa) with Callas, Picchi, Rossi-Lemeni; Rescigno, Wymetal Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Gobbi, Simoneau, Badioli, Rossi-Lemeni; Rescigno, Wymetal Carmen (Carmen) with Picchi, Guelfi, Jordan, Foldi; Perlea, Wymetal 1956 - La Forza del Destino (Preziosilla) with Tebaldi, Tucker, Bastianini, Rossi-Lemeni, Badioli, Krainik (Curra); Solti, Vassallo Gala Concert with Tebaldi, Tucker, Bastianini, Changalovich; Buckley, Solti  1957 - Mignon (Mignon) with Misciano, Moffo, Nadell, Wildermann, Foldi; Gavazzeni, Baldridge Cavalleria Rusticana (Santuzza) with Sullivan, MacNeil, Nadell, Kramarich/Fraher; Kopp, Rosing La Gioconda (Laura) with Farrell, Tucker/Di Stefano, Protti, Wildermann, Kramarich, Tallchief (solo dancer); Serafin, Vassalo Marriage of Figaro (Cherubino) with Steber, Moffo, Berry, Gobbi, Badioli, Nadell; Solti, Hartleb Adriana Lecouvreur (Princess) with Tebaldi, Di Stefano, Gobbi, Krainik (Mlle. Dangeville); Serafin, Vassallo 1958 - [Opening Night] Falstaff (Quickly) with Gobbi, Tebaldi, MacNeil, Canali, Moffo, Misciano; Serafin, Piccinato Il Trovatore (Azucena) with Ross, Bjoerling, Bastianini, Wildermann; Schaenen, Piccinato Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Gobbi, Misciano, Corena, Montarsolo, Canali; Schaenen, Piccinato Aïda (Amneris) with Rysanek, Bjoerling, Gobbi, Wildermann; Sebastian, Piccinato 1960 - [Opening Night] Don Carlo (Eboli) with Roberti, Tucker, Gobbi, Christoff, Mazzoli; Votto, West Aïda (Amneris) with Roberti/Price, Bergonzi/Ottolini, Merrill, Mazzoli; Votto, Maestrini 1961 - Barber of Seville (Rosina) with Bruscantini, Alva, Corena, Christoff, Magrini; Cillario, Frigerio |

GS: The audience

varies from country to country and from city to city, but for me the

audience all over the world has represented the great love of a career

which has lasted 39 years. It is a love which I have locked away

in my heart just as one locks a precious gem in a jewel casket.

GS: The audience

varies from country to country and from city to city, but for me the

audience all over the world has represented the great love of a career

which has lasted 39 years. It is a love which I have locked away

in my heart just as one locks a precious gem in a jewel casket.

Giulietta Simionato obituary

One of the greatest Italian

opera singers, noted for her versatile and distinctive voice

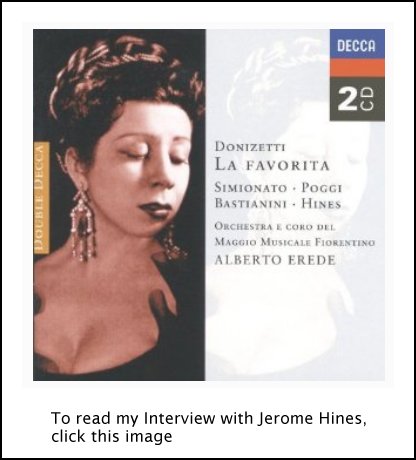

By Patrick O'Connor Published in The Guardian on Friday 7 May 2010 11.19 EDT Giulietta Simionato, who has died aged 99, was one of the greatest Italian opera singers of her generation. She was a beautiful woman and a vivid actor. Like her great friend Maria Callas, with whom she sang often, Simionato had the ability to invest whatever she was singing with an individual quality. Her voice was not as powerful as that of some of the other famous Italian contraltos and mezzos, but it was immediately recognisable. She was able to deliver each word and phrase with a rich palette of colours, and to use the characteristic rapid vibrato to sing a wide range of parts. Although Simionato's career was long, and her repertory stretched from Monteverdi, Cimarosa and Handel to Bartók, Honegger and Strauss, it will be for her performances in the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi that she will be remembered. As well as her bel canto specialities, she sang Santuzza in Cavalleria Rusticana, the title role in Carmen, and the classic Verdi mezzo roles: Eboli in Don Carlos, Azucena in Il Trovatore, Amneris in Aïda (her Covent Garden debut, under Sir John Barbirolli, with Callas as Aïda and Joan Sutherland as the Priestess, in 1953), as well as the comic Mistress Quickly in Falstaff and the swaggering Preziosilla in La Forza del Destino. She was born in Forlì, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. She spent her early childhood in Sardinia and, at the age of eight, moved with her family to Rovigo, near Venice, where her musical and vocal skills were noticed immediately. She studied with Ettore Locatello and Guido Palumbo. "I would kill my daughter with my own hands rather than see her become a singer," said her mother, who ruled the family with cruel punishments and rages. In 1925, her mother died and Simionato resumed singing, making her stage debut in 1927 in Rossato's Nina, Non far la Stupida. While still a student, she made her professional debut in the role of Maddalena in Rigoletto, and in 1933 she was one of the winners of a singing competition in Florence. Among the judges were the conductor Tullio Serafin and the veteran soprano Rosina Storchio (the first Madama Butterfly), who told her: "Always sing like this, dear one." Although Simionato's talents were quickly noticed, her career was almost entirely in small roles throughout the remainder of the 1930s. She joined La Scala in Milan in 1936 and would make appearances there for the next 30 years. Simionato married the violinist Renato Carenzio in 1940, and it was not until after the second world war that her career took off. She was 35 when she sang Dorabella in Così Fan Tutte in Geneva in October 1945. Her success was tremendous. She repeated the role in Paris the following year and was Cherubino in Figaro with the Glyndebourne company at the first Edinburgh festival in 1947. Simionato sang the title role in Ambroise Thomas's Mignon, in October 1947, opposite the young Giuseppe di Stefano as Wilhelm Meister. The role of Mignon became especially associated with Simionato, who identified with the put-upon street-singer. It was the part in which she made her debut at La Fenice in Venice in 1948, and the following year in Mexico, where she became a great favourite. During the 1948-49 seasons, she began to sing the Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti roles in which she became a specialist as the bel canto revival got under way. Leonora in Donizetti's La Favorita, the title roles in Rossini's La Cenerentola and L'Italiana in Algeri, Romeo in Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi and Adalgisa in Bellini's Norma all became Simionato parts. She first sang Adalgisa to Callas's Norma in Mexico in 1950. During the 1950s, she established a strong link with the Salzburg festival, where she often sang with Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna State Opera. Perhaps the most memorable of their collaborations was Karajan's production of Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, designed by Caspar Neher, in 1959. The nobility and restraint of Simionato's performance is preserved on a recording. After the failure of her marriage in the late 1940s, and a liaison with a much younger singer, in the 1950s she fell in love with the distinguished physician Cesare Frugoni, who was nearly 30 years older than her. Both were married, and under Italian law unable to obtain divorces, so their relationship remained discreet. During the later part of Simionato's stage career, she enjoyed a special triumph in the first performance at La Scala of Berlioz's Les Troyens in 1960. In the summer of 1962 she sang Neris to Callas's Medea for the last time, when Callas made her final La Scala appearances. She created the role of Pirene in the world premiere of Falla's Atlántida ("too static and untheatrical," Simionato called it) the same year. One of her last appearances was at Covent Garden in 1964 as Azucena in Visconti's production of Il Trovatore. She made a round of quiet farewells, singing Adalgisa to Callas's Norma in Paris in 1965, and then took on the relatively small part of Servilia in Mozart's La Clemenza di Tito at La Piccola Scala in January 1966. Simionato retired that year. She married Frugoni after the death of his first wife, and they enjoyed 12 years of marriage until he died in 1978. An elegant, social figure, Simionato was in later years an occasional judge of singing competitions. She sang Cherubino's aria, Voi che sapete, from The Marriage of Figaro, at a tribute to Karl Böhm at the Salzburg festival in 1979. In 1995, she celebrated her 85th birthday at La Scala. Her third husband, the industrialist Florio De Angeli, died in 1996. • Giulietta Simionato, opera singer, born 12 May 1910; died 5 May 2010 |

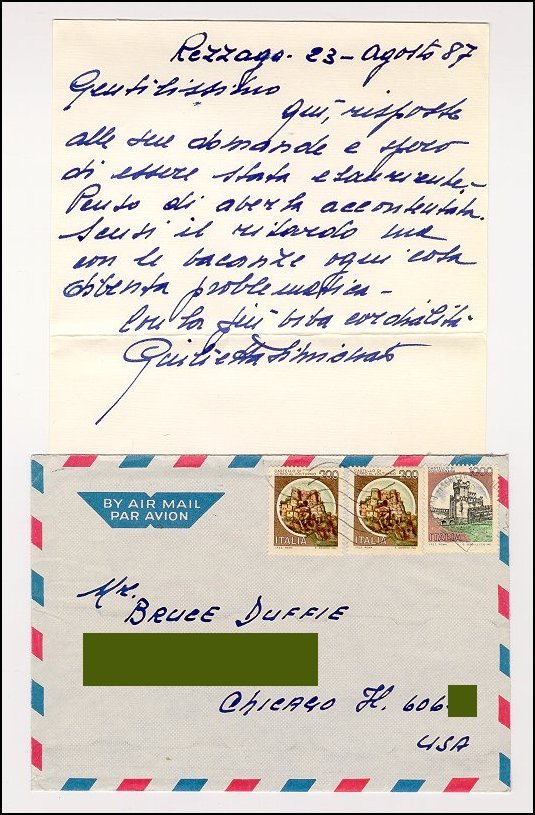

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was accomplished via letters in the postal

mail in 1987. Quotations were used during a broadcast on WNIB in

1990. The material was edited and posted on this

website in 2016. My thanks to Marina Vecci of Lyric

Opera of Chicago for providing the translations for us during the

correspondence.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.