Benjamin Lees: There really was no conscious

effort involved, it was just the way things evolved. I didn’t really

begin teaching until I got back to the United States from Europe in 1962,

and began teaching at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. I taught

there for two years and then received an offer from Queens College in New

York. Since there was considerably more money attached to it and a

chance to be in the New York area, we moved to Long Island. I was there

for two years, and the only reason I left was because the college was less

flexible in permitting its composers to attend performances and rehearsals.

I had to make a choice between teaching Harmony One and doing my own writing!

Benjamin Lees: There really was no conscious

effort involved, it was just the way things evolved. I didn’t really

begin teaching until I got back to the United States from Europe in 1962,

and began teaching at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. I taught

there for two years and then received an offer from Queens College in New

York. Since there was considerably more money attached to it and a

chance to be in the New York area, we moved to Long Island. I was there

for two years, and the only reason I left was because the college was less

flexible in permitting its composers to attend performances and rehearsals.

I had to make a choice between teaching Harmony One and doing my own writing! BD: Was that a satisfying thing, or was it

just a lark?

BD: Was that a satisfying thing, or was it

just a lark? BD: With no hard feelings?

BD: With no hard feelings? BD:

In a great number of your own works, you have used the traditional approach

— Slonimsky

calls it accessibility — which makes your music attractive

to conductors and soloists. Is this something you have consciously

built in to your pieces, or is this an outgrowth of what you wanted to write

innately?

BD:

In a great number of your own works, you have used the traditional approach

— Slonimsky

calls it accessibility — which makes your music attractive

to conductors and soloists. Is this something you have consciously

built in to your pieces, or is this an outgrowth of what you wanted to write

innately? BL:

I really don’t expect anything of the audience. I think the audience

comes in good faith to a concert, and looks at the program and says, “Ah,

yes, there will be this piece by Lees.” Some have heard this composer;

some haven’t. All they’re hoping is that the work won’t be too dreadful,

or that it’s something that they might actually enjoy. It’s really

up to the composer, in the writing of a piece, to be able to communicate in

the first instance to himself or herself. If the communication to one’s

self has been successful and really honest, then chances are that the piece

will communicate to the audience. Honestly, I’ve seen this work so

often that it’s something that I live by! I’ve been involved with audiences

who were very, very conservative, and I was warned in advance, “If

they stand up and walk out, don’t take it personally. That’s the way

they are.” And that very same audience will stand up and cheer, which

is a complete surprise.

BL:

I really don’t expect anything of the audience. I think the audience

comes in good faith to a concert, and looks at the program and says, “Ah,

yes, there will be this piece by Lees.” Some have heard this composer;

some haven’t. All they’re hoping is that the work won’t be too dreadful,

or that it’s something that they might actually enjoy. It’s really

up to the composer, in the writing of a piece, to be able to communicate in

the first instance to himself or herself. If the communication to one’s

self has been successful and really honest, then chances are that the piece

will communicate to the audience. Honestly, I’ve seen this work so

often that it’s something that I live by! I’ve been involved with audiences

who were very, very conservative, and I was warned in advance, “If

they stand up and walk out, don’t take it personally. That’s the way

they are.” And that very same audience will stand up and cheer, which

is a complete surprise. BL: I believe, after all, that the composer should

have the right to correct! While they are rehearsing a standard piece,

I have heard I don’t know how many conductors say to an orchestra, “If only

Beethoven (or Mozart) were alive, we could ask him how this should go!”

Well by God, here’s the bloody composer sitting there! Ask him while

he’s still alive! But so often, they treat the composer as somehow

a necessary impediment. So you have to be very careful about how you

ask a conductor whatever it is you want asked or corrected.

BL: I believe, after all, that the composer should

have the right to correct! While they are rehearsing a standard piece,

I have heard I don’t know how many conductors say to an orchestra, “If only

Beethoven (or Mozart) were alive, we could ask him how this should go!”

Well by God, here’s the bloody composer sitting there! Ask him while

he’s still alive! But so often, they treat the composer as somehow

a necessary impediment. So you have to be very careful about how you

ask a conductor whatever it is you want asked or corrected. BD:

Music in general.

BD:

Music in general. BL:

[Laughs] Perhaps so, unless we develop a larger audience.

I’m writing a fifth symphony, and while I’m pleased that I was asked and

I hope it’s a successful work, I keep wondering all the time what its relevancy

is in today’s society. You see, the audience still likes to be entertained,

so I always feel, somehow, more confident in writing a work for soloist

and orchestra because for the audience, it’s almost like a circus; it’s

an act. They love to come and hear the pianist because they have a

chance to see his fingers fly! And they love to hear a violinist because

they can look at the violinist and they see what he’s doing. The soloist

in the twentieth century has become the star. The conductor is the

aide-de-camp to the soloist, and the composer is a very, very distant third.

The composer is not a glamorous figure; the soloist is a glamorous figure,

and our audience today, our society today, loves the lives of the rich and

the famous, and that’s the soloist! And the orchestra is the soloist’s

tool. The audience cannot wait for the last note to expire before they

stand up and scream and applaud. The same thing happens in ballet.

BL:

[Laughs] Perhaps so, unless we develop a larger audience.

I’m writing a fifth symphony, and while I’m pleased that I was asked and

I hope it’s a successful work, I keep wondering all the time what its relevancy

is in today’s society. You see, the audience still likes to be entertained,

so I always feel, somehow, more confident in writing a work for soloist

and orchestra because for the audience, it’s almost like a circus; it’s

an act. They love to come and hear the pianist because they have a

chance to see his fingers fly! And they love to hear a violinist because

they can look at the violinist and they see what he’s doing. The soloist

in the twentieth century has become the star. The conductor is the

aide-de-camp to the soloist, and the composer is a very, very distant third.

The composer is not a glamorous figure; the soloist is a glamorous figure,

and our audience today, our society today, loves the lives of the rich and

the famous, and that’s the soloist! And the orchestra is the soloist’s

tool. The audience cannot wait for the last note to expire before they

stand up and scream and applaud. The same thing happens in ballet. BD: Have we thrown a new joker into all of

this by the fact that so many of these pieces by most of the fifty thousand

are being recorded and preserved, if not commercially, at least on private

tapes?

BD: Have we thrown a new joker into all of

this by the fact that so many of these pieces by most of the fifty thousand

are being recorded and preserved, if not commercially, at least on private

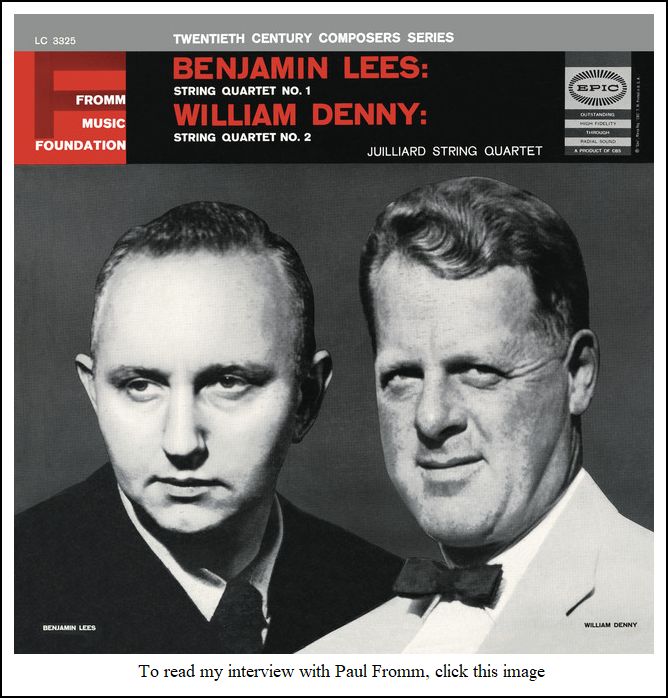

tapes? BD: What about the recordings? Those have

a bit more permanence simply because they are around more and have a wider

distribution. Are you pleased with those?

BD: What about the recordings? Those have

a bit more permanence simply because they are around more and have a wider

distribution. Are you pleased with those? BL:

There are also minor masterpieces. Is a minor masterpiece the same

as a major masterpiece? [Both laugh] Let’s take the most mundane

and the most obvious. If a Mozart Number Forty or a Jupiter or a Beethoven Fifth is a major masterpiece, then what

do we consider a minor masterpiece? A Saint-Saëns Violin Concerto? A Bruckner Fourth? They’re certainly performed

often enough.

BL:

There are also minor masterpieces. Is a minor masterpiece the same

as a major masterpiece? [Both laugh] Let’s take the most mundane

and the most obvious. If a Mozart Number Forty or a Jupiter or a Beethoven Fifth is a major masterpiece, then what

do we consider a minor masterpiece? A Saint-Saëns Violin Concerto? A Bruckner Fourth? They’re certainly performed

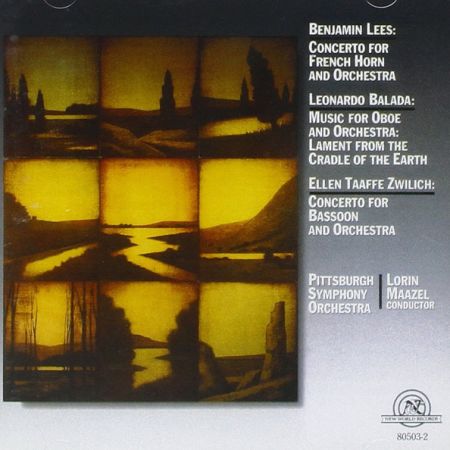

often enough.| New Haven, Conn.—The Irving S.

Gilmore Music Library at Yale University announced that it has acquired

the entire archive of renowned American composer Benjamin Lees. The comprehensive

archive, which was a gift from the composer, includes manuscript sketches

and scores for all of Lees's compositions, correspondence, concert programs,

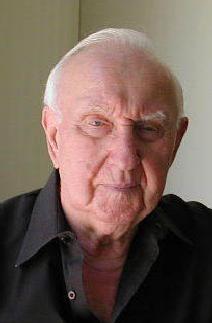

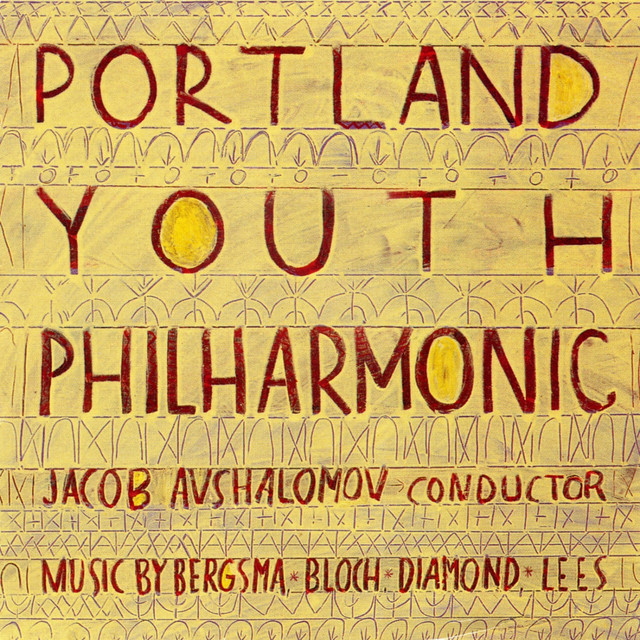

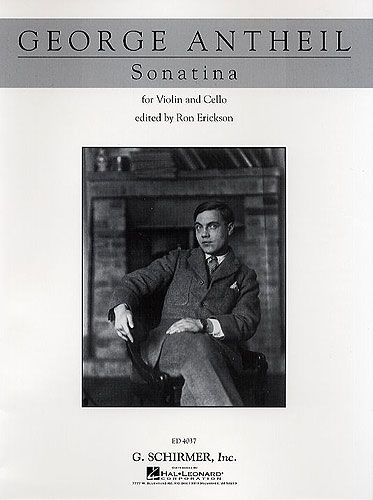

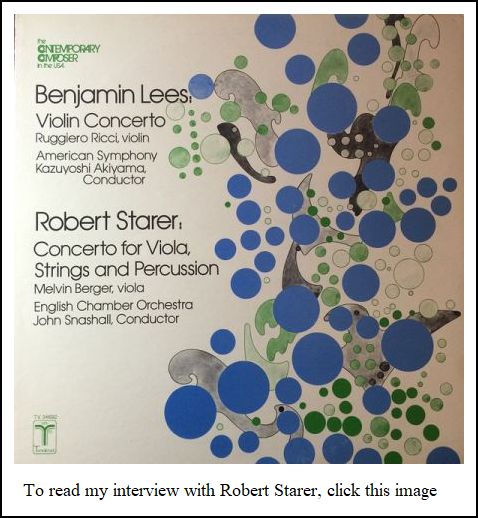

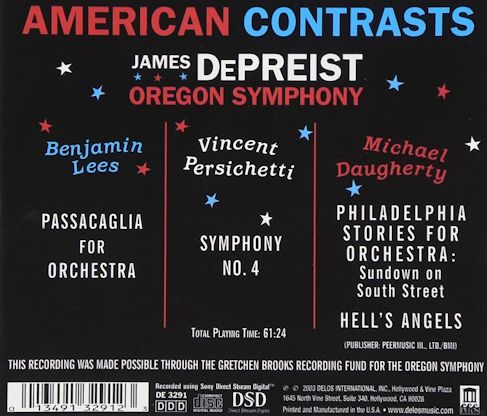

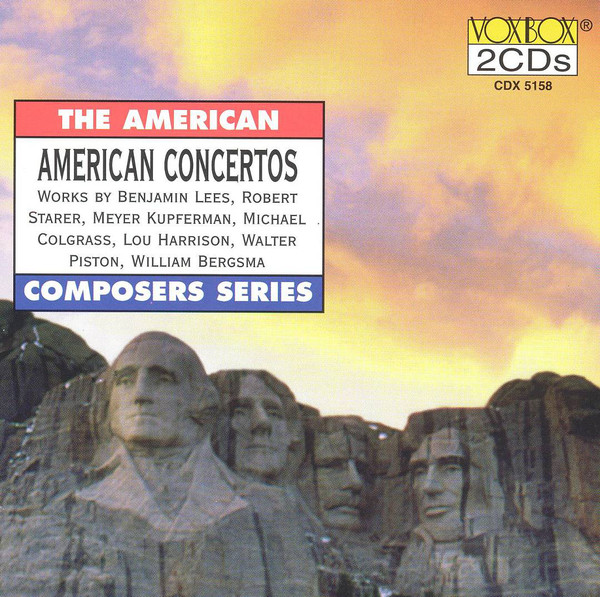

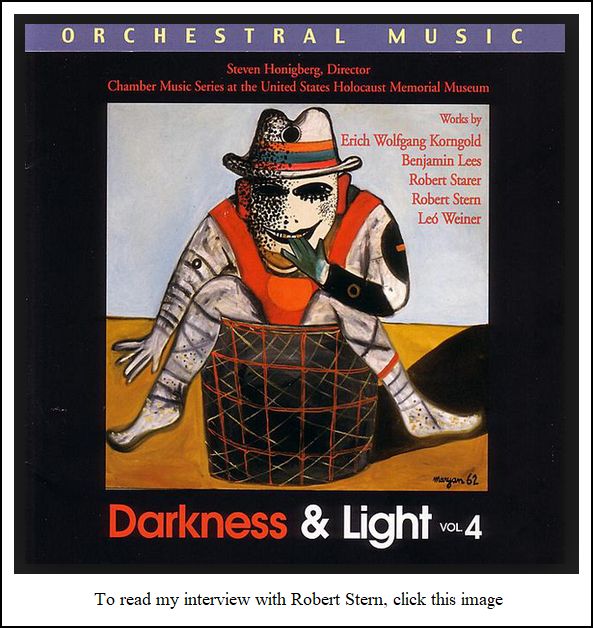

reviews, photographs, and biographical materials. Born to Russian parents in Harbin, China in 1924, Benjamin Lees arrived in the U.S. in 1925. He and his parents settled in San Francisco where he began his piano studies at the age of five. After military service in World War II he attended the University of Southern California to study composition, harmony, and theory. Shortly after completing his studies he was introduced to the legendary American composer George Antheil and thus began almost five years of intense study in advanced composition and orchestration, during which the two formed a close and lasting friendship. Throughout his distinguished career, Lees has composed in a wide variety of genres. His works have been commissioned and performed by ensembles and soloists throughout the United States and Europe, including the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte Carlo. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has commissioned two of his works, Piano Trio No. 2 "Silent Voices" and "Night Spectres" for unaccompanied cello. As a composer, Lees is especially renowned for his orchestral works, which are represented by five symphonies and numerous concertante works that feature soloist or small instrumental groups with orchestra. Writing in the August 2007 issue of The Strad, Robert Markow called Lees' Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra, "an outstanding model of the form." Other concertante works for small ensembles include concertos for woodwind quintet, brass choir, percussion ensemble, all with orchestra. The composer's many awards include a Fromm Foundation Award (1953), two Guggenheim Fellowships (1954, 1966), a Fulbright Fellowship (1956), a UNESCO Award for String Quartet No. 2 (1958), and the Sir Arnold Bax Society Medal, the first awarded to a non-British composer (1958). He also received a Grammy nomination in 2004 for his Symphony No. 5. Benjamin Lees' music is published exclusively by Boosey & Hawkes. For information about the Benjamin Lees archive contact: Kendall Crilly Andrew W. Mellon Music Librarian Irving S. Gilmore Music Library kendall.crilly@yale.edu (203) 432-0495 |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on June 13, 1987.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1989, 1994 and 1999.

A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern

University. This transcription was made and posted on this website

in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.