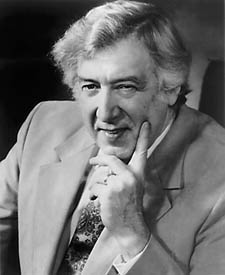

| Gunther (Alexander) Schuller is

a significant American composer, conductor, and music educator. He was of

a musical family; his paternal grandfather was a bandmaster in Germany before

emigrating to America; his father was a violinist with the New York Philharmonic

Orchestra. He was sent to Germany as a child for a thorough academic training;

returning to New York, he studied at the Saint Thomas Choir School (1938-1944);

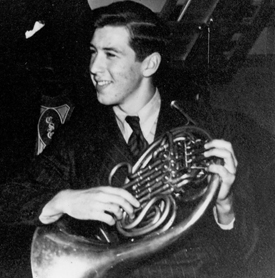

also received private instruction in theory, flute, and horn. Gunther Schuller became an accomplished horn player and flute player. At age 15 he played horn professionally with the New York City Ballet orchestra (1943); then was 1st horn in the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (1943-1945) and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in New York (1945-1959). He taught at the Manhattan School of Music in New York (1950-1963), the Yale University School of Music (1964-1967), and the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where he greatly distinguished himself as president (1967-1977). He was also active at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood as a teacher of composition (1963-1984), head of contemporary-music activities (1965-1984), artistic co-director (1969-1974), and director (1974-1984). In 1984-1985 he was interim music director of the Spokane (Washington) Symphony Orchestra; then was director of its Sandpoint (Idaho) Festival. In 1986 he founded the Boston Composers' Orchestra. In 1988 he was awarded the 1st Elise L. Stoeger Composer's Chair of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center in New York. In 1975 he organized Margun Music to make available unpublished American music. He founded GunMar Music in 1979. In 1980 he organized GM Recordings. During his youth, Gunther Schuller attended the Precollege Division at the Manhattan School of Music. He became fascinated with jazz; and played the horn in a combo conducted by Miles Davis (1949-1950). He also began to compose jazz pieces. In his multiple activities, Schuller tried to form a link between serious music and jazz; he popularized the style of "cool jazz" (recorded as Birth of the Cool). In 1955 Schuller and jazz pianist John Lewis founded the Modern Jazz Society, which gave its first concert in Town Hall, New York, that same year and later became known as the Jazz and Classical Music Society. While lecturing at Brandeis University in 1957 he launched the slogan "third stream" to designate the combination of classical forms with improvisatory elements of jazz as a synthesis of disparate, but not necessarily incompatible, entities. He became an enthusiastic advocate of this style and wrote many works according to its principles. As part of his investigation of the roots of jazz, he became interested in early ragtime and formed, in 1972, the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble; its recordings of Scott Joplin's piano rags in band arrangement were instrumental in bringing about the "ragtime revival." In 1959 Gunther Schuller gave up performance to devote himself to composition, teaching and writing. He has conducted internationally and studied and recorded jazz with such greats as Dizzy Gillespie and John Lewis among many others. Schuller has written over 160 original compositions. In his own works he freely applied serial methods, even when his general style was dominated by jazz. Among his works in the "third stream" style: Transformation (1957, for jazz ensemble), Concertino (1959, for jazz quartet and orchestra; one of its movements, Progression in Tempo, has sometimes been performed separately), Abstraction (1959, for nine instruments), the opera The Visitation (1966), and Variants on a Theme of Thelonious Monk (1960, for 13 instruments), which was recorded by Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and Bill Evans. He also orchestrated Scott Joplin's only known surviving opera Treemonisha for the Houston Grand Opera's premier production of this work. His modernist orchestral work Where the Word Ends, organized in four movements corresponding to those of a symphony, premiered at the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 2009. Gunther Schuller published the manual Horn Technique (New York, 1962; 2nd edition, 1992). He is the author of two major books on the history of jazz: the very valuable study Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development (3 vols., New York: Oxford University Press, 1968; New printing 1986) and The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945 (Oxford University Press. 1991). A volume of his writings appeared as Musings (New York, 1985). Other publications: Gunther Schuller: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987); The Compleat Conductor (Oxford University Press, 1998). Schuller is editor-in-chief of Jazz Masterworks Editions, and co-director of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra in Washington, D.C. Another recent effort of preservation was his editing and posthumous premiering at Lincoln Center in 1989 of Charles Mingus' immense final work, Epitaph, subsequently released on Columbia/Sony Records. Gunther Schuller has been the recipient of many awards. He received honorary doctorates in music from Northwestern University (1967), the University of Illinois (1968), Williams College (1975), the New England Conservatory of Music (1978), and Rutgers University (1980). In 1967 he was elected to membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1980 to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. He received the Ditson Conductor's Award in 1970. In 1989 he received the William Schuman Award of Columbia University for "lifetime achievement in American music composition". In 1991 he was awarded a MacArthur Foundation grant. In 1994 he won the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his orchestral work, Of Reminiscences and Reflections (1993), composed for the Louisville Orchestra in memory of his wife who died in 1992. In 1993, Down Beat magazine honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award for his contribution to jazz. He received two Grammy Awards: Best Album Notes - Classical: Gunther Schuller (notes writer) for for Footlifters performed by Gunther Schuller (1976), and Best Chamber Music Performance: Gunther Schuller (conductor) & the New England Conservatory Ragtime Ensemble for Joplin: The Red Back Book (1974). His notable students include Irwin Swack and John Ferritto. Gunther is the father of jazz percussionist George Schuller and bassist Ed Schuller. |

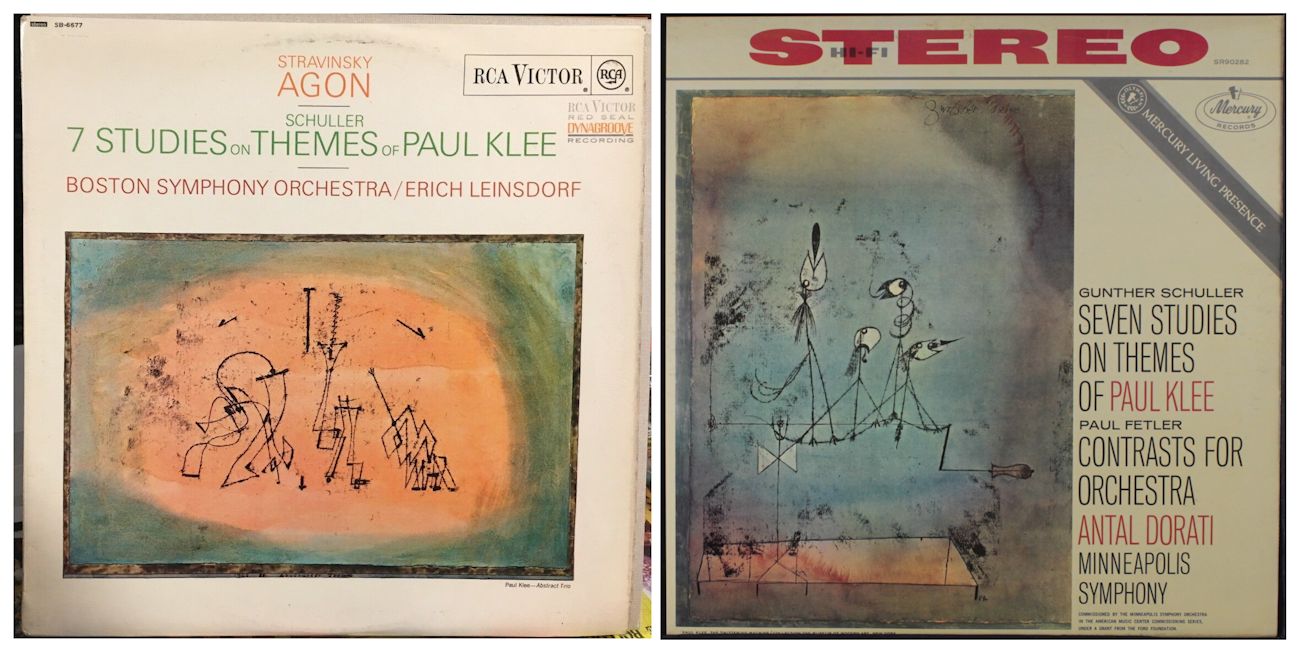

Gunther Schuller: It's the Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee,

to give it its full title; it's usually called the Klee Studies, which is, I guess, my most

popular piece by far, for reasons that I cannot entirely explain. I

don't necessarily feel it's my best piece, but it certainly seems to have

won a place in the repertory of lots and lots of orchestras. At latest

counting, it's been played by something like 312 orchestras, many of them

repeating it in various seasons. So it's sort of a hit, I guess.

Gunther Schuller: It's the Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee,

to give it its full title; it's usually called the Klee Studies, which is, I guess, my most

popular piece by far, for reasons that I cannot entirely explain. I

don't necessarily feel it's my best piece, but it certainly seems to have

won a place in the repertory of lots and lots of orchestras. At latest

counting, it's been played by something like 312 orchestras, many of them

repeating it in various seasons. So it's sort of a hit, I guess. BD: Has there always been this reaction by the public against

contemporary music?

BD: Has there always been this reaction by the public against

contemporary music? BD: Who has put in this gulf — is it

the public or the composers...

BD: Who has put in this gulf — is it

the public or the composers... BD: But record company A is not going to record The Visitation, and then lead record company

B to do it also, and record company C...

BD: But record company A is not going to record The Visitation, and then lead record company

B to do it also, and record company C... GS: I write in a certain style or conception, and yet sometimes

I use some of the same basic raw materials because I happen to be a 12-tone

composer. I find that the pieces that I write based on this same material

are quite different in character and mood, and even what we call the "sonic

surface" — the thing that you hear — and

I think that's as it should be!

GS: I write in a certain style or conception, and yet sometimes

I use some of the same basic raw materials because I happen to be a 12-tone

composer. I find that the pieces that I write based on this same material

are quite different in character and mood, and even what we call the "sonic

surface" — the thing that you hear — and

I think that's as it should be!  BD: Should they be resurrected at all?

BD: Should they be resurrected at all? BD: Are you pleased with what you hear when it gets performed?

BD: Are you pleased with what you hear when it gets performed? GS: I would always put, not maybe in the absolute top of the

heap but somewhere along the top, originality. Next, memorability, recognizability,

and then subsidiary to that, contributing to that are things like one's musical

imagination and one's instincts, and of course one's background and skill

and knowledge. One other important thing that I find in composing

— or writing a book or painting or any artistic endeavor

— is that as much as 50 percent of the creation resides in the

critical faculty which evaluates what you are creating as you are creating.

It's simultaneous. In other words, most people think, "I have a blank

piece of paper and I'm now going to fill it with music." Or, "I'm a

painter and I'm gonna fill the canvas with designs." That active act

of putting something out is what most people think is the creative act.

Well, that's only half of it because while you're doing that, you better also

be very good in evaluating whether what you are doing is worth doing; whether

it fits the piece and whether it's a logical extension of what you've just

created the second before. The whole continuity of this process is

something which you have to always be checking out. So the critical

faculty and working in conjunction with the creative faculty are the two major

components of that whole process.

GS: I would always put, not maybe in the absolute top of the

heap but somewhere along the top, originality. Next, memorability, recognizability,

and then subsidiary to that, contributing to that are things like one's musical

imagination and one's instincts, and of course one's background and skill

and knowledge. One other important thing that I find in composing

— or writing a book or painting or any artistic endeavor

— is that as much as 50 percent of the creation resides in the

critical faculty which evaluates what you are creating as you are creating.

It's simultaneous. In other words, most people think, "I have a blank

piece of paper and I'm now going to fill it with music." Or, "I'm a

painter and I'm gonna fill the canvas with designs." That active act

of putting something out is what most people think is the creative act.

Well, that's only half of it because while you're doing that, you better also

be very good in evaluating whether what you are doing is worth doing; whether

it fits the piece and whether it's a logical extension of what you've just

created the second before. The whole continuity of this process is

something which you have to always be checking out. So the critical

faculty and working in conjunction with the creative faculty are the two major

components of that whole process. GS: Apart from giving great pleasure to those who can receive

those pleasures, I think the most important thing is that it is a reflection

of our particular society at any given time — in the

time and period that we live — and the things that

concern us and move us and touch us both intellectually and emotionally.

This reflection, however, is viewed through our own particular personal viewer,

so to speak, because naturally what comes into this is our particular education

and background and environment and genetics that created us, or me, in this

case, as an individual. But insofar that I'm a thinking person and that

I am reacting to the world around me and reflecting it in my thinking, it's

bound to come out in my creation. Now that doesn't mean necessarily

that I'm a political composer. I'm not writing pamphlet music or Republican

music or Democratic music, or whatever it might be. But for sure, these

things, in some subliminal way, present themselves. Now specifically

musically, the tradition that preceded us — including,

in my case, a deep involvement with the whole jazz tradition

— comes out in my music, sometimes overtly or consciously, sometimes

subliminally. All of those things are then combined together as a kind

of intellectual and emotional reaction to, and reflection of, my life and

my times as I see them. But music is very special. If you were

talking to a writer now, or a poet, or even a painter who works with much

more specifically relatable figures, designs, words, you'd have a somewhat

different answer. The point being that music is this incredible language

where nothing is specified. Music cannot say anything specific, despite

all of Richard Strauss's great protestations that he could even describe a

fork and a knife in music, which is totally ludicrous. Yes, you can

create moods and characters and feelings, perhaps, but even those are very

unspecific. I'm so happy I'm a musician to be able to deal with this.

The beauty of music is that music cannot say anything specific

— even with a program note and a storyline — and

therefore it can say anything and everything. That's totally unique

about music; there's no other artistic language that can do that, because

everything else is more specified.

GS: Apart from giving great pleasure to those who can receive

those pleasures, I think the most important thing is that it is a reflection

of our particular society at any given time — in the

time and period that we live — and the things that

concern us and move us and touch us both intellectually and emotionally.

This reflection, however, is viewed through our own particular personal viewer,

so to speak, because naturally what comes into this is our particular education

and background and environment and genetics that created us, or me, in this

case, as an individual. But insofar that I'm a thinking person and that

I am reacting to the world around me and reflecting it in my thinking, it's

bound to come out in my creation. Now that doesn't mean necessarily

that I'm a political composer. I'm not writing pamphlet music or Republican

music or Democratic music, or whatever it might be. But for sure, these

things, in some subliminal way, present themselves. Now specifically

musically, the tradition that preceded us — including,

in my case, a deep involvement with the whole jazz tradition

— comes out in my music, sometimes overtly or consciously, sometimes

subliminally. All of those things are then combined together as a kind

of intellectual and emotional reaction to, and reflection of, my life and

my times as I see them. But music is very special. If you were

talking to a writer now, or a poet, or even a painter who works with much

more specifically relatable figures, designs, words, you'd have a somewhat

different answer. The point being that music is this incredible language

where nothing is specified. Music cannot say anything specific, despite

all of Richard Strauss's great protestations that he could even describe a

fork and a knife in music, which is totally ludicrous. Yes, you can

create moods and characters and feelings, perhaps, but even those are very

unspecific. I'm so happy I'm a musician to be able to deal with this.

The beauty of music is that music cannot say anything specific

— even with a program note and a storyline — and

therefore it can say anything and everything. That's totally unique

about music; there's no other artistic language that can do that, because

everything else is more specified.

GS: I would like, in the ideal, for audiences to be perceptive

and discriminating and understanding of the musical elements as I work with

them; to recognize relationships in the piece — melodic,

motivic, thematic, structural relationships; and to love the harmonies that

I write because I'm a strong harmonic composer. This is an area where

most people are at their weakest. Most people listen very superficially.

I'm not condemning people! This is a matter of education. The

musical and artistic illiteracy in this country is just staggering.

So I could answer your question by saying I don't expect anything because

I know the state of what's out there, in terms of appreciating my music,

Elliott Carter's music, Milton Babbitt's music,

Schoenberg's music, Stravinsky's music, Beethoven's last quartets, Monteverdi's

Orfeo or whatever! There is

no education towards that. In our entire school system there's nothing

that prepares you to listen to the music of George Perle.

GS: I would like, in the ideal, for audiences to be perceptive

and discriminating and understanding of the musical elements as I work with

them; to recognize relationships in the piece — melodic,

motivic, thematic, structural relationships; and to love the harmonies that

I write because I'm a strong harmonic composer. This is an area where

most people are at their weakest. Most people listen very superficially.

I'm not condemning people! This is a matter of education. The

musical and artistic illiteracy in this country is just staggering.

So I could answer your question by saying I don't expect anything because

I know the state of what's out there, in terms of appreciating my music,

Elliott Carter's music, Milton Babbitt's music,

Schoenberg's music, Stravinsky's music, Beethoven's last quartets, Monteverdi's

Orfeo or whatever! There is

no education towards that. In our entire school system there's nothing

that prepares you to listen to the music of George Perle. BD: I'm glad you've stuck by your guns!

BD: I'm glad you've stuck by your guns! BD: In addition

to the composing and the lecturing, you've been involved in the musical education

business for a long time. How have the students changed over 20, 30,

40 years?

BD: In addition

to the composing and the lecturing, you've been involved in the musical education

business for a long time. How have the students changed over 20, 30,

40 years? BD: There's no understanding of it?

BD: There's no understanding of it? BD: What's the answer, then?

BD: What's the answer, then?[Note: It is interesting to look back on these thoughts from 1981 and 1988. That was the dawning of the CD age. Since then, many new and previously-unrecorded works have appeared on compact discs, including quite a respectable number by Gunther Schuller. Ironically, as this is being prepared for presentation on this website, the CD as a viable commodity seems to be in serious decline. Ipods, MP3s, downloads and other devices are becoming the primary delivery system for music, while YouTube and other "social media" are adding visual recordings to the ever-expanding availability of all aspects of our society.]

Gunther Schuller Gunther Schuller's orchestral works include some of the classics of the

modern repertoire written for the major orchestras of the world. Prominent

among these are several masterful examples in the "Concerto for Orchestra"

genre, though not all of them take that title. Most recently, the Boston

Symphony Orchestra and James

Levine premiered Where the Word Ends in February 2009

[Photo at right]. Semyon Bychkov and the

WDR Symphony Orchestra brought Where the Word Ends to the

2010 Proms in London. An earlier work is Spectra (1958),

alongside such works as the Concerto for Orchestra No. 1: Gala Music

(1966), written for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Concerto

for Orchestra No. 2 (1976) for the National Symphony Orchestra;

and Farbenspiel (Concerto for Orchestra No. 3) (1985), written

for the Berlin Philharmonic. The title of the latter, translatable as "play

of colors," echoes the visual metaphor of Spectra.

Gunther Schuller's orchestral works include some of the classics of the

modern repertoire written for the major orchestras of the world. Prominent

among these are several masterful examples in the "Concerto for Orchestra"

genre, though not all of them take that title. Most recently, the Boston

Symphony Orchestra and James

Levine premiered Where the Word Ends in February 2009

[Photo at right]. Semyon Bychkov and the

WDR Symphony Orchestra brought Where the Word Ends to the

2010 Proms in London. An earlier work is Spectra (1958),

alongside such works as the Concerto for Orchestra No. 1: Gala Music

(1966), written for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Concerto

for Orchestra No. 2 (1976) for the National Symphony Orchestra;

and Farbenspiel (Concerto for Orchestra No. 3) (1985), written

for the Berlin Philharmonic. The title of the latter, translatable as "play

of colors," echoes the visual metaphor of Spectra.

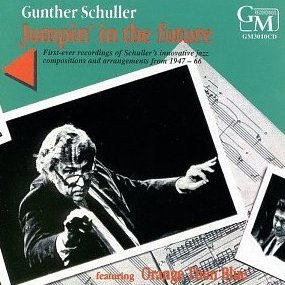

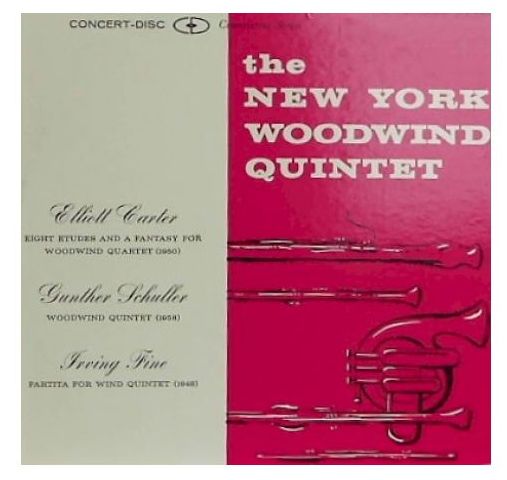

Only one of Schuller's large orchestral pieces takes the generic title of "symphony": his colorful Symphony, written in 1965 for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and premiered that year. Schuller himself, however, has described his Of Reminiscences and Reflections (1993) as a "symphony for large orchestra." Written for the Louisville Orchestra and winner of the 1994 Pulitzer Prize in Music, Of Reminiscences and Reflections is Schuller's large-scale memorial to his wife of 49 years, Marjorie Black. (Another orchestral tribute to Marjorie is The Past Is the Present, written for the centennial of the Cincinnati Symphony and premiered in May 1994.) One of his first works performed by a major orchestra was his Symphony for Brass and Percussion, played in 1949 by Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic; his Symphony No. 3, In Praise of Winds (1981) is also for wind ensemble. He has also written a Chamber Symphony and a work for solo organ titled, simply, Symphony. Concertos and concertante works for solo or small ensemble with orchestra form a large subgroup within Schuller's output. With his two piano concertos (1962 and 1981), two violin concertos (1976 and 1991), two horn concertos (1943 and 1976), and concertos for trumpet, for flute, and for viola, Schuller has championed as soloists unusual but deserving instruments, including alto saxophone, bassoon, contrabassoon, organ, and double bass. He has shown a predilection for works combining small ensemble and orchestra in his classic Contrasts for Wind Quintet and Orchestra (1961), Concerto Festivo for Brass Quintet and Orchestra, and the Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra, to name a few. For concert band are Diptych for Brass Quintet and Concert Band (1967), Eine Kleine Posaunemusik for trombone and band (1980), and Song and Dance for violin and band (1990). As in his concertos, Schuller's chamber music is for a range of both traditional and non-traditional forces. These works appear frequently on the programs of local and internationally known ensembles throughout the United States, Europe, and Japan. His String Quartet No. 3 (1986) is prominent in the repertoire of, and has been recorded by, the Emerson String Quartet, and the Juilliard Quartet has championed his String Quartet No. 4 (2002). The outstanding, exotic mixed-media work Symbiosis (1957) for violin, piano, and percussion, written for a Metropolitan Opera Orchestra violinist and his wife, a dancer, is but one example of Schuller's embrace of unusual performance opportunities and instrumental combinations. Not to be overlooked are Schuller's original jazz compositions such as Teardrop and Jumpin' in the Future, works that epitomize the composer's “Third Stream” approach, which combines the total-chromatic language of Schoenberg and the structural sophistication of the contemporary classical composer with the ensemble fluidity and swing of jazz. An educator of extraordinary influence, Schuller served on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music and Yale University; he was, for many years, head of contemporary music activities (succeeding Aaron Copland) as well as a director of the Tanglewood Music Center, and served as President of the New England Conservatory of Music. He has published several books and recently embarked on the writing of his memoirs. — April 2011 [Text from G. Schirmer Inc Website] |

The first of these two interviews was recorded in Evanston, IL on

May 8, 1981, and a portion was used on WNIB later that day. The second

interview was recorded in Chicago on October 15, 1988, and portions (along

with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1990 and again in 1995. This

transcription was made and posted on this website in 2011.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.