|

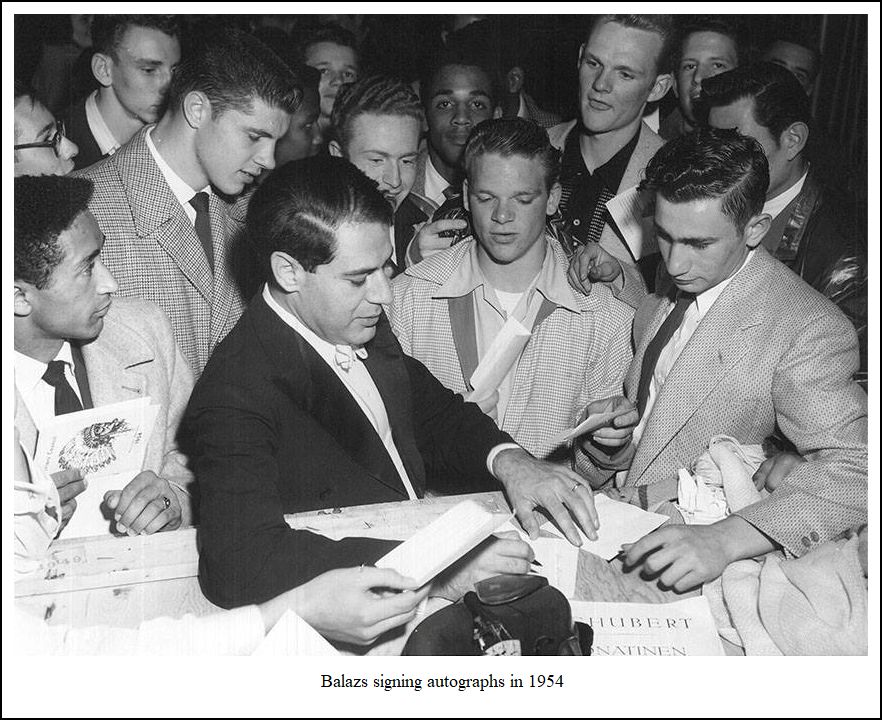

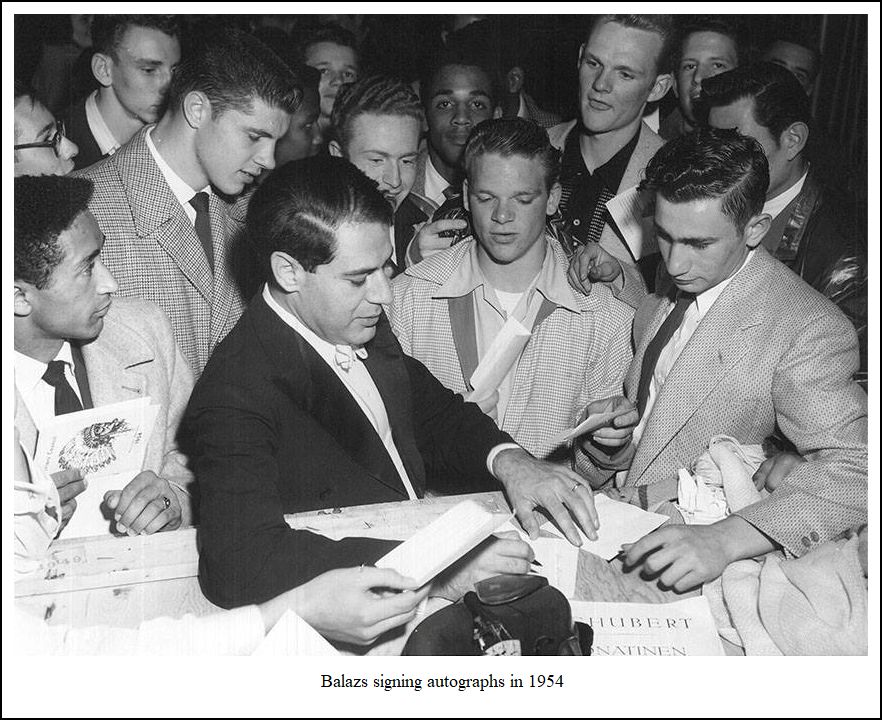

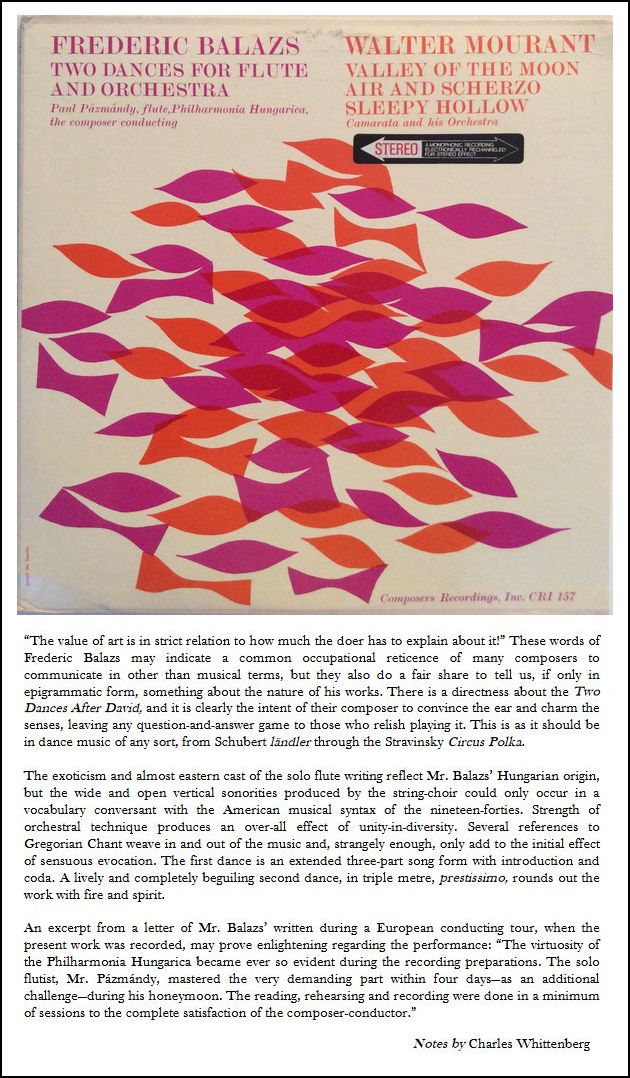

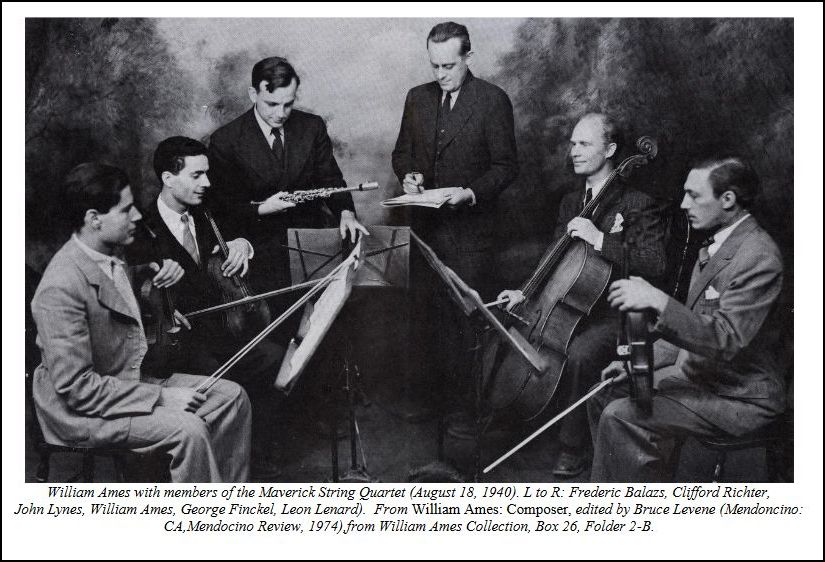

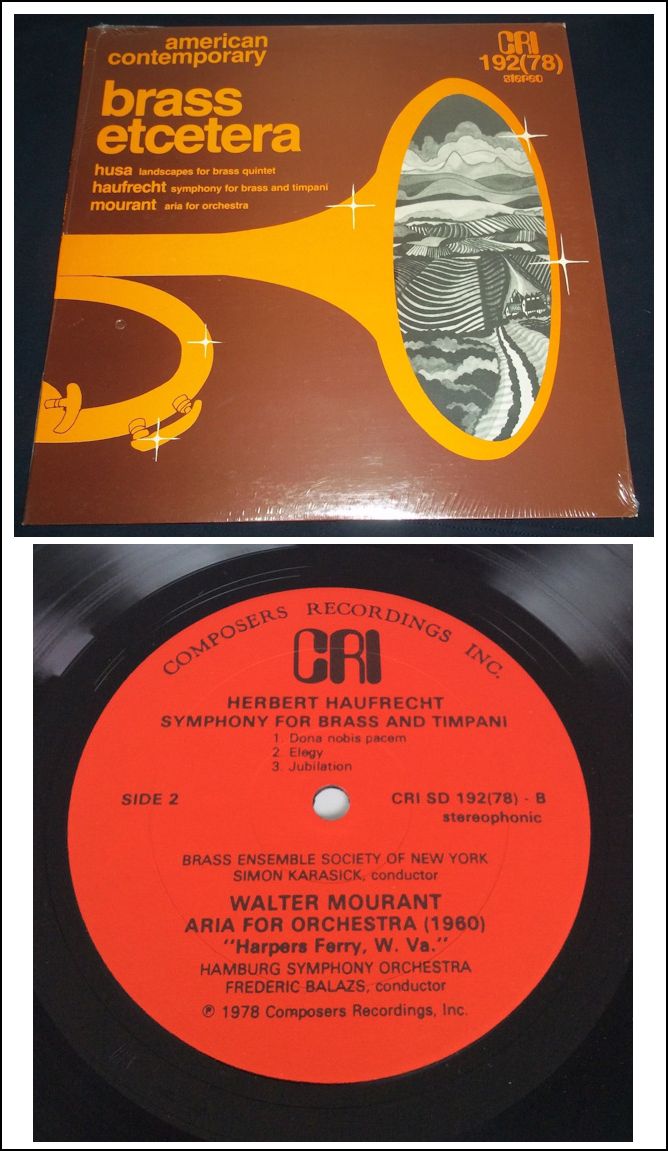

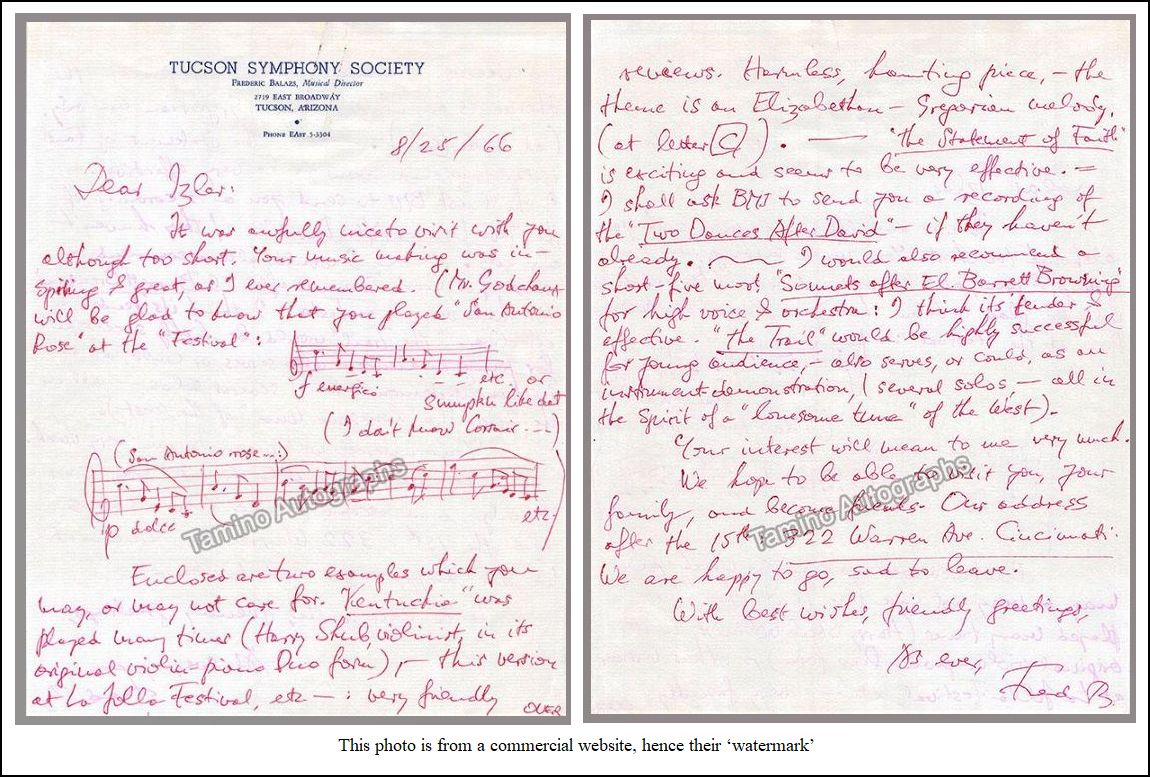

In the words of the great pianist, Claudio Arrau, Frederic Balazs is "a brilliant conductor of rare gifts with musicianship, intelligence, and inspirational capacity of great depth." Born in Budapest, he studied violin as a child under Béla Bartók, Ernst Von Dohnányi and Zoltán Kodály. He became concert violinist and concertmaster of the Budapest Symphony at the age of 17. He acquired his intense affinity with the technique and spirit of the orchestra by working under such greats as Bruno Walter, Toscanini, Ormandy, and Furtwängler. Balazs (December 12, 1920 [not 1919 according to him when I asked about the discrepancy, and he complimented me for being so thorough] - June 2, 2018) came to the United States and joined the Army after Pearl Harbor, serving with several adventuresome "distinctions". As a result of his service, Balazs was awarded a lifetime honorary membership to the American Composers Alliance upon returning home. At the age of 23, his Divertimento was performed in California, at a meeting of the International Society for Contemporary Music. His music was compared to that of Bartók, and his string quartets have received unusually high praise, and comparison with the great quartets of Shostakovich, Ives, and Piston. His music has been characterized as plaintive, lyrical, and also romantic, or vigorous and high-spirited. Balazs is known for his work in building and establishing young ensembles, such as the Wichita Falls Symphony and the Tucson Symphony, both of which blossomed into major ensembles under his direction. He was often sought out as a director of training orchestra programs in seminars and festivals. Composer Miklós Rózsa comments that Balazs is "an excellent conductor who works with and engenders reciprocal warmth and enthusiasm." Conductor Antal Dorati singled him out as "a splendid violinist and a conductor of rare gifts." Through his long life and wide experiences, Frederic Balazs possessed an unlimited repertoire of symphonic, concerto, operatic, and pops literature. As a champion of contemporary music, he recorded many premiere works for CRI, a label that was originally founded by the American Composers Alliance. He received the Alice M. Ditson Award for outstanding contributions to American music, honorary membership in the International Mark Twain Literary Society, and many other awards and honors. He lived for many years in San Luis Obispo, California, where he

founded Music and the Arts for Youth (MAY), to assist and award young

talent. His work with, and on behalf of children and youth in music was

featured on the NBC Evening News as the "Musical Genius and the Pied

Piper of California." Maestro Balazs is currently living in Arizona, where he composes full-time. He was celebrated in 2003, during the 75th anniversary celebration of the Tucson Symphony, and his "Song--after Walt Whitman" for orchestra performed by the TSO with the Arizona Boys' Chorus, and "Prayers from the Ark" for children's voices and piano, both major works, were performed in celebration of the Boys Chorus's 70th anniversary in November, 2009. His piano was a gift from his friend and colleague, ACA composer Walter Mourant. == Biography mostly from the American

Composers Alliance website, as well as other sources. * * *

* *

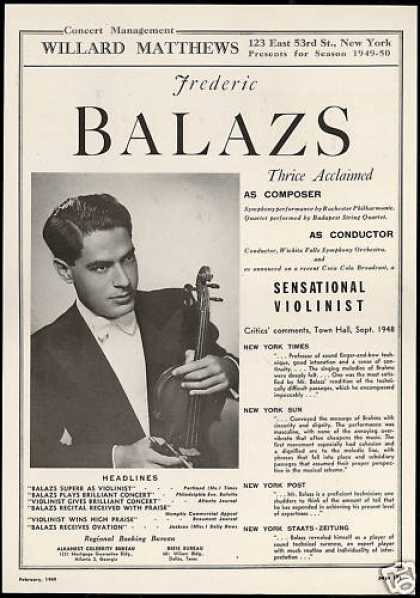

Frederic Balazs was born in Budapest in 1920 and was graduated cum laude from the Royal Academy of Music. He came to the United States during World War II and, after serving four years in the armed forces, settled temporarily in Philadelphia. He has appeared as guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in Lewisohn Stadium, New York City; Grant Park Symphony Orchestra. Chicago; Oklahoma City Symphony Orchestra and numerous groups in Canada and Europe. Mr. Balazs has also contributed to educational procedures, the assisting of young talent and sociological aspects of music. In recognition of his services on behalf of music for young people, he was recently named chairman of the Youth Orchestras Project of the National Federation of Music Clubs. Mr. Balazs’ many-sided interests are also reflected in his appointment as regional chairman for the Metropolitan Opera Auditions-of-the-Air. The importance of folk music in the heritage of many American composers prompted him to organize the American Contemporary Music Center in Tucson, Arizona, where he now resides with his wife and four small children. He was recently director of the summer festival at Woodstock, where he conducted the orchestra and also served as first violin of the resident string quartet, in the European tradition. He is now permanent Conductor and Music Director of the Tucson Symphony Orchestra. == Biography from the

CRI record jacket

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on September 7, 1987. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.