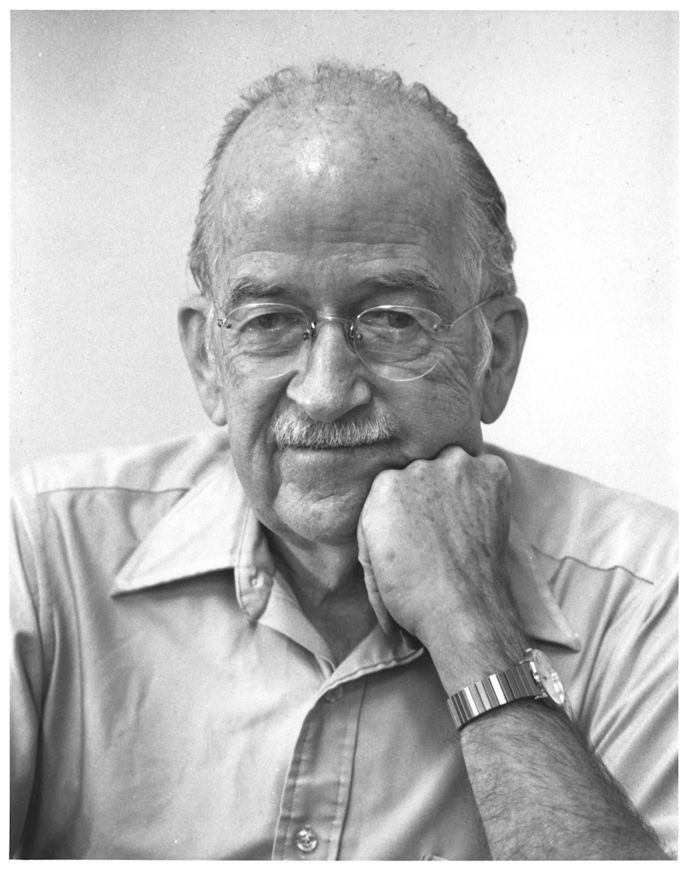

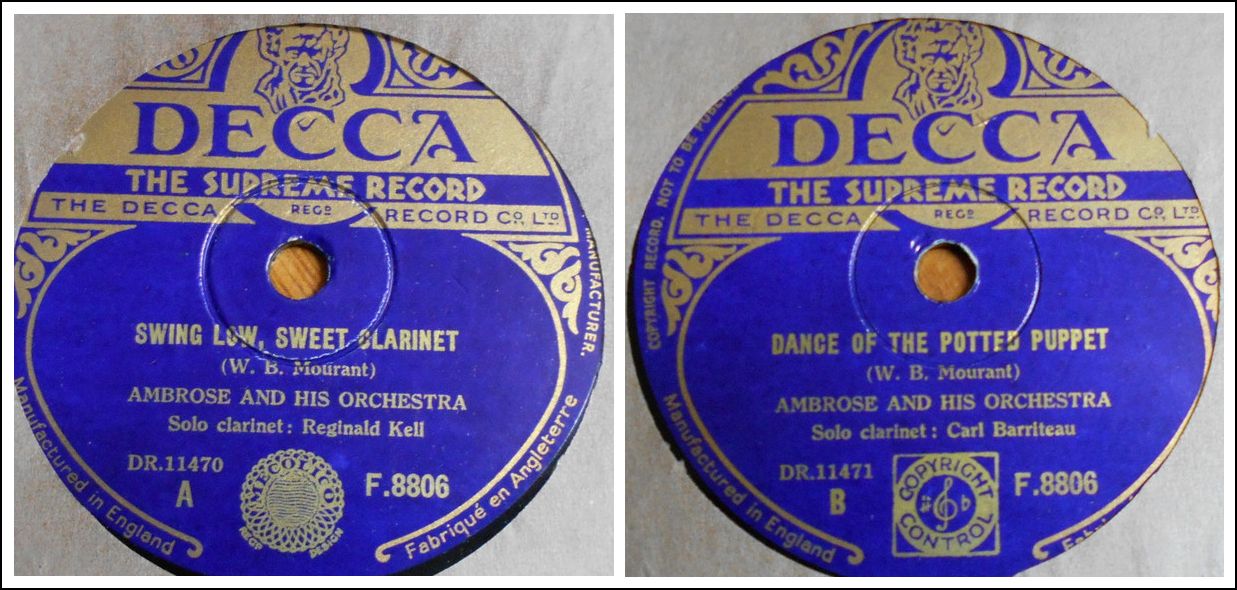

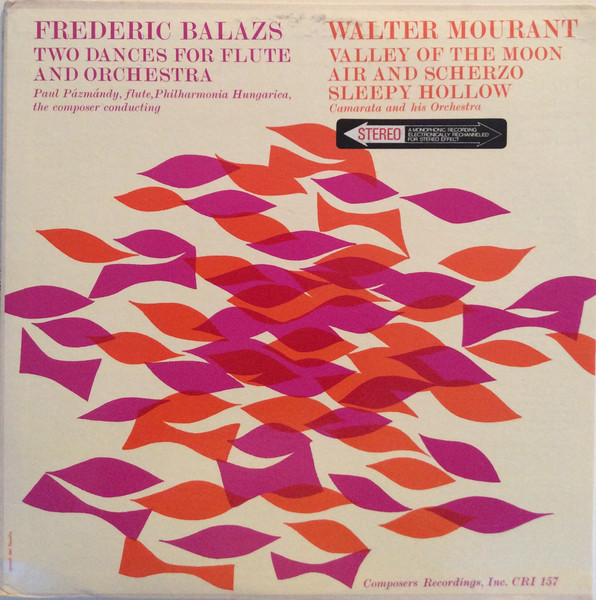

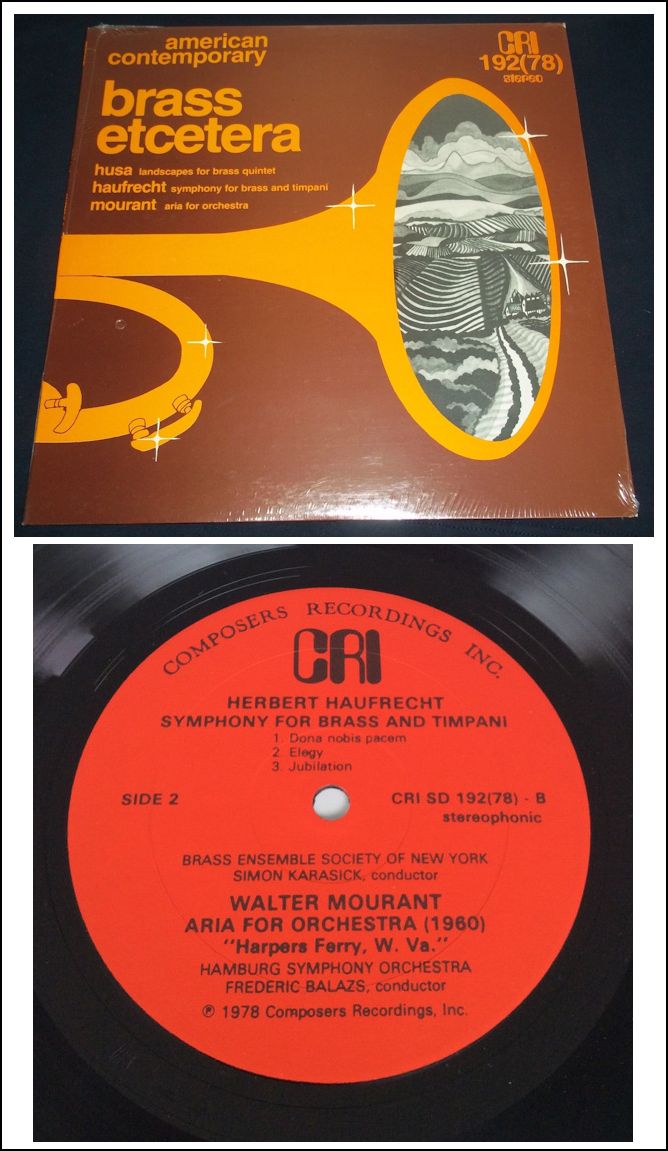

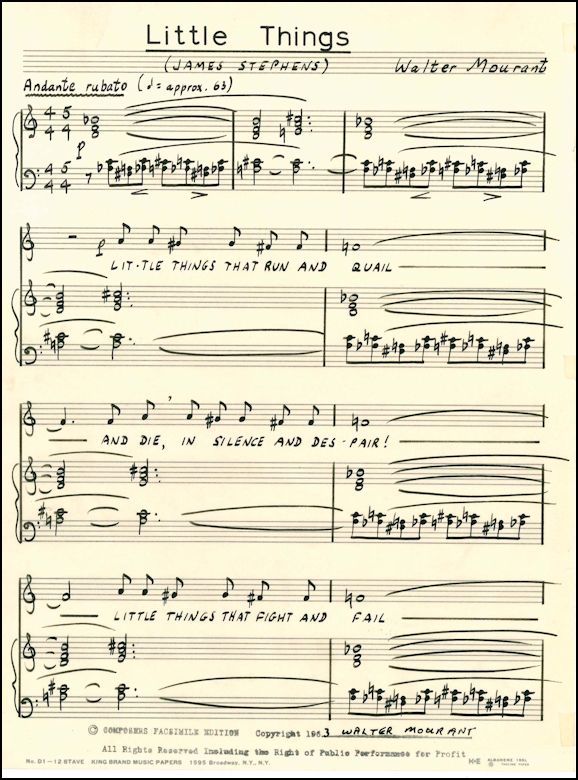

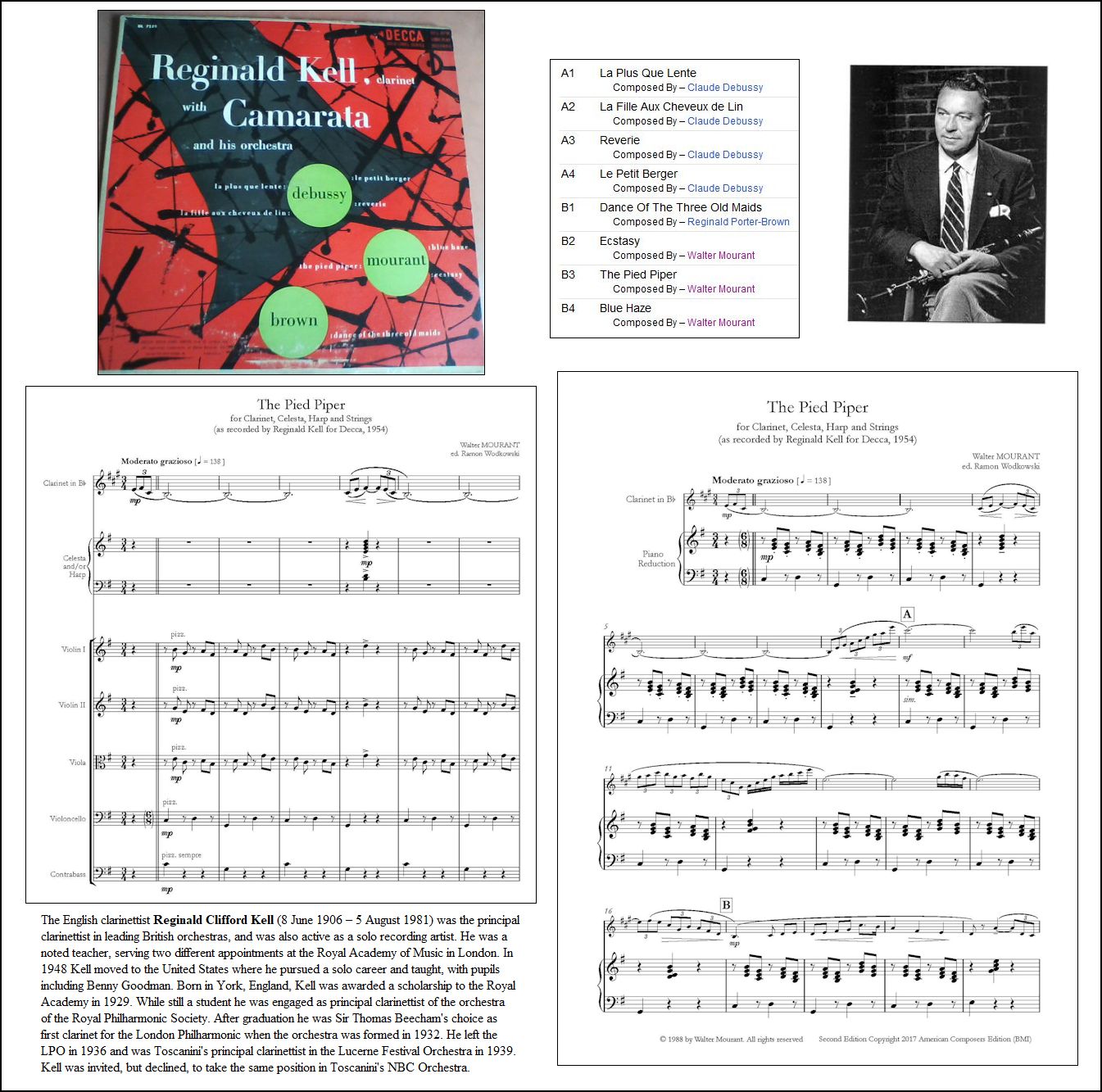

| Walter Mourant (August 29, 1910

- May 4, 1995) attended the Eastman School of Music from 1931-1936,

where he received his Bachelor's and Master's in Music. His first

orchestra work was performed in 1932 and published by Carl Fischer. He

attended the Juilliard School of Music from 1937-1938. Various assignments

while working at CBS and NBC included writing a 'March of Time' theme

for the March of Time program, a theme for Westinghouse program, orchestrating

the Robert Montgomery Show at NBC, and arranging for the Raymond Scott

orchestra at CBS. (Source: American Composers Alliance; exact

date of death from Musica website)

|

|

He was the older brother of composer and bandleader Raymond Scott (b. Harry Warnow), and is credited with steering his younger (and eventually also very famous) brother into a career in music. Warnow was born in Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) to Jewish parents, and came with them to the United States when he was a boy. Warnow grew up in Brooklyn, New York. He attended Public School 100 and Eastern District High School, where he was a soloist as a violinist in the school's orchestra. When he was 17, Warnow became the Massel Opera's musical director. From there, he became the Ziegfeld Follies' musical director. That was followed by a stint as bandleader for the Music Box Revue. Warnow enjoyed a lengthy and versatile career with the CBS Radio network. He was CBS music director in the early 1930s, and hired his younger brother Harry as a keyboardist in 1931. Warnow conducted the orchestra on the CBS radio program Your Hit Parade from 1939 to his death in 1949. A 1941 newspaper article described Warnow as "the busiest man in radio", noting that his conducting duties included not only Your Hit Parade, but Helen Hayes Theatre and We, the People. He also conducted his orchestras for The Jack Berch Show, the "Matinee Theatre" program, and Ed Wynn's "Happy Island" program. Warnow also conducted the orchestra for the "Sound Off" Radio show, 1946, New York City, sponsored by the U.S. Army to encourage post World War II recruitment. Emcee Arno Tanney, aka "The Chant" would sing/chant army recruiting commercials like a drill seargeant in his signature booming baritone to the rapid fire rhythm of the "Duckworth Chant" - "Join the Army, it's for you, better pay and college too, Sound Off!, 1, 2, Sound Off! 3, 4, - 1, 2, 3, 4, Sound Off...Sound Off!" Warnow appeared as himself with his band in the Paramount Pictures release Paramount Headliner: The Star Reporter (1938), and also produced a Broadway musical-comedy, What's Up? (1943-1944).

In the 1940s, Warnow conducted and arranged for Frank Sinatra while the singer was signed to Columbia Records, then owned by the CBS network. In 1949, Warnow and his orchestra recorded a Capitol Records album, Sound Off, named for the Sound Off Chant, which was featured on the album along with some marches and other patriotic music. |

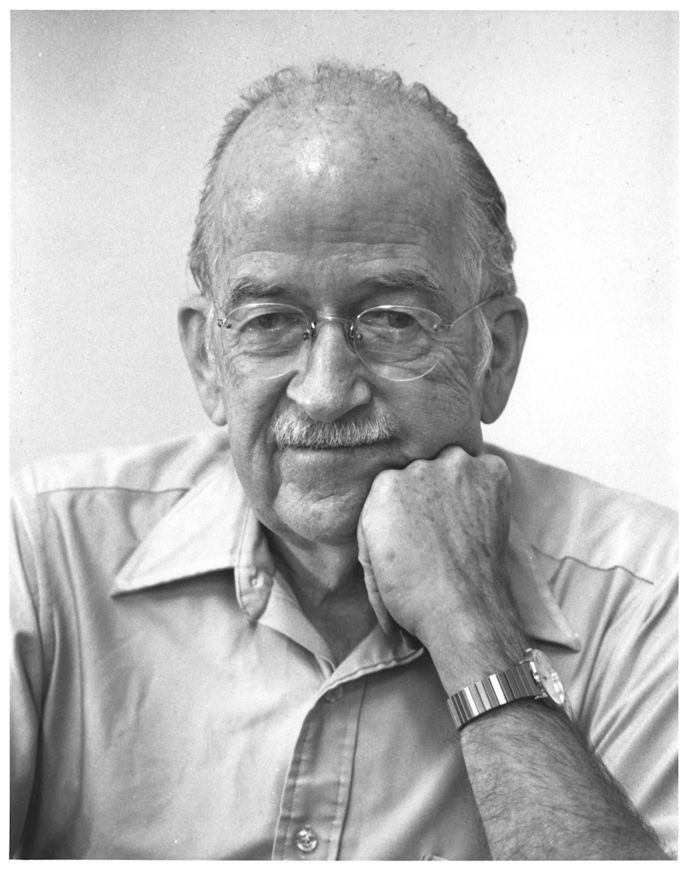

A declared neo-Romanticist, Hanson wrote music at once tuneful, vigorous, and accessible. Hanson’s earliest compositions, dating from around 1914, included songs, piano pieces, and two symphonic works, and culminated in his music for the California Forest Play of 1920. In 1923 he won the Prix de Rome with which he took up residence in Italy as the first American composer to be named a Rome Fellow. While there he completed his first symphony (“Nordic”), whose first performance by the Augusteo Orchestra he conducted in Rome, and wrote his great choral piece, The Lament for Beowulf, his String Quartet, and his two symphonic poems, North and West and Lux Aeterna. Early in 1924 Hanson returned to the United States to lead the New York Symphony Orchestra in his North and West and to conduct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in the American premiere of his Nordic Symphony. Upon the invitation of President Rush Rhees and George Eastman, he became the second director of the recently established Eastman School of Music, taking office shortly before his 28th birthday. During the ensuing decades Hanson became one of the country’s most influential music educators. The Eastman School under his leadership developed into an institution in which students could receive a well-rounded education while concentrating upon their professional studies. Perhaps his greatest overall influence upon music was as protagonist of American culture. During the early decades of the century, music in America was dominated by European music and Old-World influences. As an American composer striving to be heard, Hanson was fired with zeal to bring native music to the fore. In 1925, in a daring move for those years, he initiated the American Composers Concerts, during which works by our own writers were performed, many for the first time, by professional musicians from the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, assisted by the School’s artist faculty and advanced students. In 1930 he began an even more ambitious project: the annual Festivals of American Music, which continued through 1971, by which time more than 200 compositions had been given their first performance, with the composers being present for the rehearsals and the public concerts. While it may appear that the greatest emphasis was upon orchestral music, each Festival also featured a ballet, opera, chamber and choral music. Hanson’s inclusion of American works at symphony concerts he offered as guest conductor with major symphonies throughout the country and his national radio broadcasts over the NBC network during the 1930s and 1940s helped to create a large audience for contemporary works by our own composers. He was justly called the Dean of American Composers and spokesman for music in America. The outward signs of recognition accorded him by the public took the form of citations for his contributions to the quality of American life and culture, 34 honorary doctorates, election into the most prestigious national and international organizations, and buildings named in his honor. He died on February 26, 1981.--- --- --- ---

--- --- --- --- --- --- ---

--- ---

In 1926, Rogers accepted a teaching position at the Hartt School of Music in Connecticut. The next year, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship (1927–1929), which enabled him to study with Frank Bridge in London and Nadia Boulanger in Paris. When he returned to the United States in 1929, he was invited by Howard Hanson to join the faculty at the Eastman School of Music; he would spend the duration of his career at Eastman serving as professor of composition and chair of the composition department (1930–1967) until his retirement in 1967. Many of his students enjoyed distinguished and prominent careers as composers and educators themselves; this number includes Mary Jeanne van Appledorn, Dominick Argento, Jack Beeson, William Bergsma, David Diamond, Kenneth Gaburo, Ulysses Kay, John La Montaine, Burrill Phillips, Gardner Read, Vladimor Ussachevsky, Robert Ward, and many others. Prof. Rogers’s output as a composer included more than 25 large orchestral works, including five symphonies; five operas; three cantatas and several other large-scale choral works; and numerous works of chamber music. He received commissions from the Ford Foundation, the Koussevitzky Music Foundation, the Louisville Orchestra, the String Foundation of Cleveland, and several other organizations. Among his numerous awards are the Loeb Composition Prize (1923), the David Bispham Medal (for the opera The Marriage of Aude, completed 1931), election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1947), the Alice M. Ditson Award for opera (for The Warrior, 1947), and a Fulbright Award (1953), in addition to the aforementioned Pulitzer Traveling Scholarship and Guggenheim Fellowship. He was also awarded honorary degrees from Valparaiso University (1959) and Wayne University (1962). His compositions have been performed by the Metropolitan Opera, New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, Philadelphia Sinfonietta, Cincinnati Symphony, and other major orchestras in the United States and Europe. Additionally, Rogers’s treatise The Art of Orchestration (1951) was long regarded as an essential reference for students of composition. |

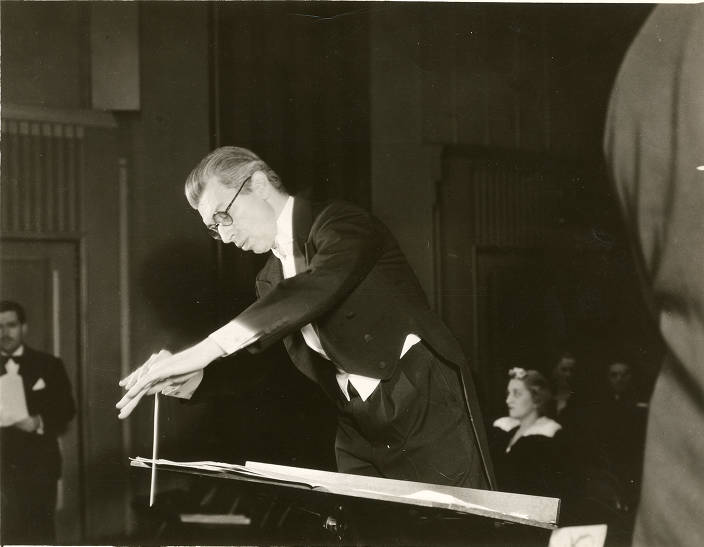

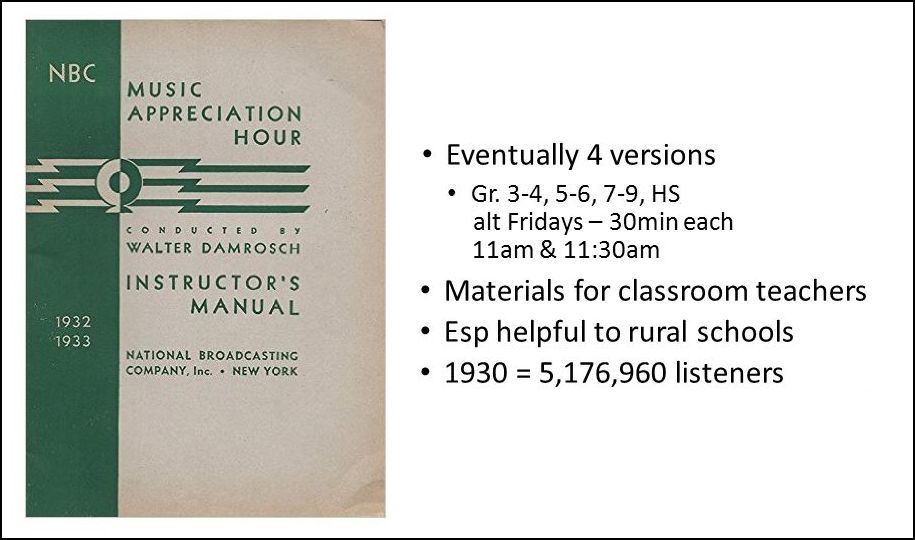

Walter Johannes Damrosch (January 30, 1862 – December 22, 1950) was a German-born American conductor and composer. He is best remembered today as long-time director of the New York Symphony Orchestra and for conducting the world premiere performances of George Gershwin's Piano Concerto in F (1925) and An American in Paris (1928). Damrosch was also instrumental in the founding of Carnegie Hall. He also conducted the first performance of Rachmaninov's third piano concerto with Rachmaninov himself as a soloist. Damrosch was the National Broadcasting Company's music director under David Sarnoff, and from 1928 to 1942, he hosted the network's Music Appreciation Hour, a popular series of radio lectures on classic music aimed at students. (The show was broadcast during school hours, and teachers were provided with textbooks and worksheets by the network.) According to former New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg in his collection Facing the Music, Damrosch was notorious for making up silly lyrics for the music he discussed in order to "help" young people appreciate it, rather than letting the music speak for itself.

|

|

After studying ballet, piano and flute as a child, Chertok forwent her senior year of high school to attend the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she studied with Marjorie Tyre and Carlos Salzedo. She then moved to New York City where she was staff harpist with the CBS Television Orchestra for many years, appearing on shows such as The Arthur Godfrey Show and Ed Sullivan's Toast of the Town. Chertok recorded several albums, both for solo harp as well ensemble work. Her solo work included her own compositions, many of which employed an innovative jazz idiom. On her LP Strings of Pearl she was accompanied by bongo player Willie Rodriguez. Other recordings include transcriptions for harp of music by Loeillet, Purcell and others. Chertok also convinced contemporary composers, including Elie Siegmeister, Nuncio Mondello, Edmund Haines, Sergiu Natra and William Mayer, to write for the harp. As a result, numerous pieces are dedicated to her, including music of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, and Jean Françaix. Chertok was president of the American Harp Society and was on the faculty of several colleges and universities in the New York City area. Several of her students have gone on to distinguished careers as concert harpists. She served as judge at the International Harp Contest in Israel, and a prize named in her honor was awarded in 1982, 1985, 1988 and 1992. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on July 25, 1987. I included a piece of his (without interview) on the in-flight program of Delta Airlines that ran in September and October of 1987. Portions of the interview were broadcast (along with music) on WNIB in 1990, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.