| Burrill

Phillips (November 9, 1907, Omaha, Nebraska – June 22, 1988, Berkeley, California)

was an American composer, teacher, and pianist. Phillips studied at the

Denver College of Music with Edwin Stringham and at the Eastman School of

Music in Rochester, NY, with Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers. In 1929 he

married Alberta Phillips (who wrote many of his librettos); they had a daughter,

Ann Phillips Basart (b. 1931) and a son (Stephen Phillips, 1938–86). Because

of privations due to the Great Depression, Ann was adopted and raised by her

maternal grandparents; she was not reunited with her parents until 1959.

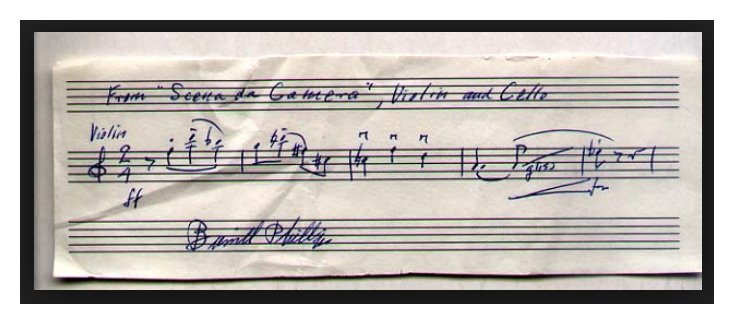

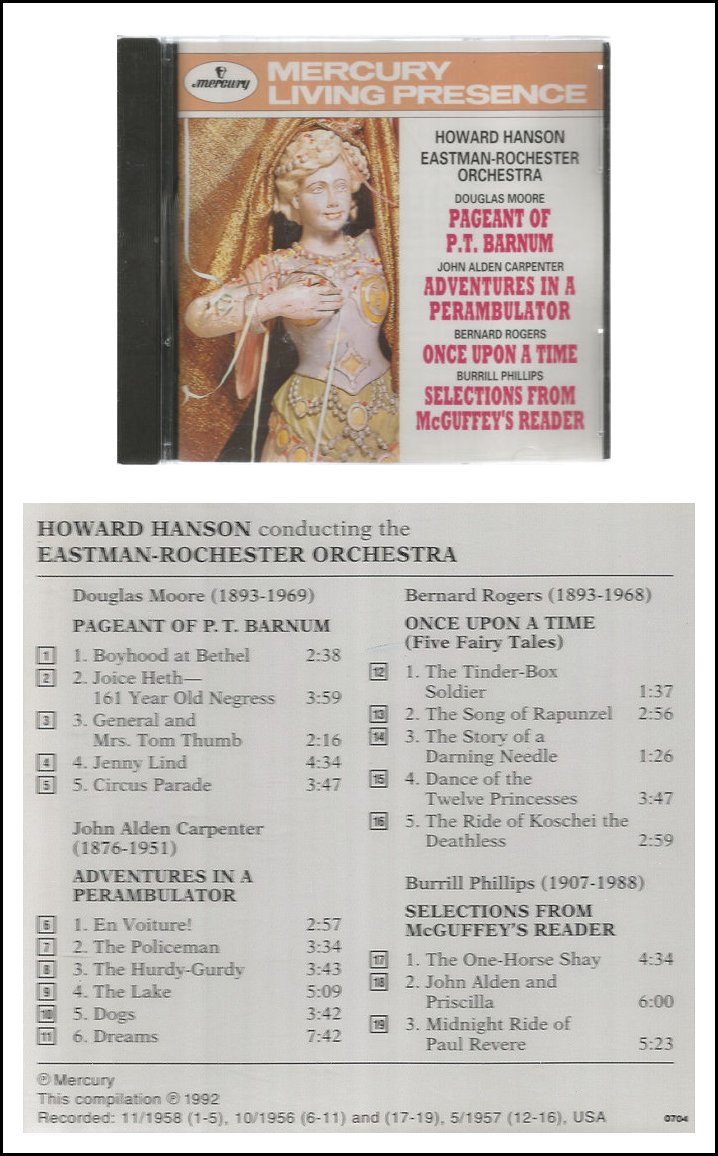

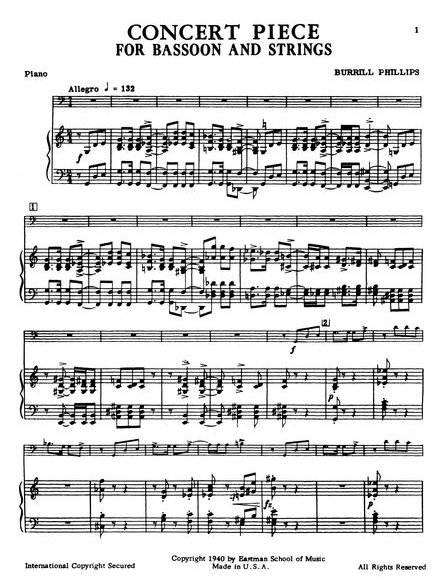

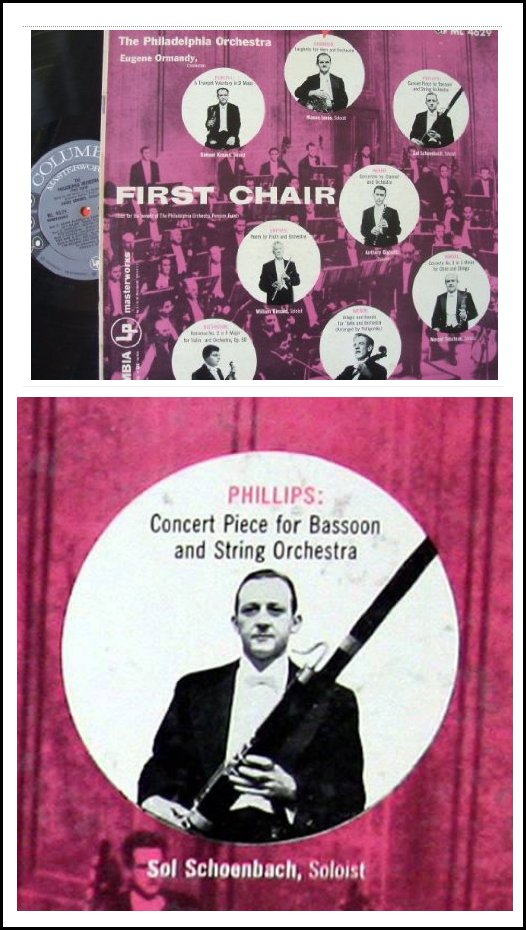

Phillips's first important work was Selections from McGuffey's Reader, for orchestra, based on poems by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. The early style of this work, stressing melody, self-consciously American references, and jazzy rhythms, has tended to overshadow his later compositions. By the 1940s he had turned to a more astringent and expressive idiom. In 1960 his String Quartet Number Two was premiered at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. by the Paganini Quartet, with the composer present, and broadcast on live FM radio. In the early 1960s he turned to free serial techniques, less sharply accented rhythms, and increasing fantasy. Phillips taught composition and theory at Eastman (1933–49), the University of Illinois (1949-64), the Juilliard School of Music (1968–69), and Cornell University (1972-73). His students include Jack Beeson, Kenneth Gaburo, Steven Stucky, David Ward-Steinman, and Ben Johnston. He was a Fulbright Lecturer in Barcelona, Spain, in 1960-61, and received Guggenheim fellowships in 1942-43 and 1961–62, when the entire Phillips family reunited in Paris. His scores and sketches are housed in the Burrill Phillips archive, Special Collections, Sibley Library, Eastman School of Music, in Rochester, NY. |

Burrill Phillips: Oh! They're fifty years old, as a matter

of fact, and were one of the first group of pieces that I could hear played

by an orchestra. They were written for that, and they were first performed

at Eastman. Is the history on the cover of the album?

Burrill Phillips: Oh! They're fifty years old, as a matter

of fact, and were one of the first group of pieces that I could hear played

by an orchestra. They were written for that, and they were first performed

at Eastman. Is the history on the cover of the album? BD: By and large, are you basically pleased with the performances

you've heard of your music?

BD: By and large, are you basically pleased with the performances

you've heard of your music? BP: There are so many kinds of audiences that it's hard to

say. That was one of the things I learned from Roy Harris. He

believed that, and he usually wrote music for the audience with a general

background that he expected to hear it for the first time. That kind

of thing could lead, of course, to some bad results, but I don't think it

did in his case. In any audience there are people who are well educated

in classical music, but they have heard very little contemporary music.

That's one thing you have to take into consideration. You might not

do anything about it, but it has a kind of formative influence on your career,

and on what you ultimately feel will give you success. Occasionally

I've written educational pieces that were written specially for teaching

purposes. This is ensemble music, not necessarily something that one

person plays. For instance, there was a piece that I've never heard

called Three Easy Pieces for String Orchestra [published by the Interlochen Press in 1959].

It's done a lot at that summer music camp up in Michigan. I can tell

from the royalties that I get that they still do it, and I've never heard

a note of that piece. [Laughs]

BP: There are so many kinds of audiences that it's hard to

say. That was one of the things I learned from Roy Harris. He

believed that, and he usually wrote music for the audience with a general

background that he expected to hear it for the first time. That kind

of thing could lead, of course, to some bad results, but I don't think it

did in his case. In any audience there are people who are well educated

in classical music, but they have heard very little contemporary music.

That's one thing you have to take into consideration. You might not

do anything about it, but it has a kind of formative influence on your career,

and on what you ultimately feel will give you success. Occasionally

I've written educational pieces that were written specially for teaching

purposes. This is ensemble music, not necessarily something that one

person plays. For instance, there was a piece that I've never heard

called Three Easy Pieces for String Orchestra [published by the Interlochen Press in 1959].

It's done a lot at that summer music camp up in Michigan. I can tell

from the royalties that I get that they still do it, and I've never heard

a note of that piece. [Laughs]

BD: Is music art, or is music entertainment?

BD: Is music art, or is music entertainment?

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on October 19, 1986.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1992 and

1997. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.