JB:

I rather imagine that teaching composition hasn’t changed very much, at least

where I am. I learned a good deal about how to go about it from Otto Luening, whom I was

assisting at first, and who’s still very much alive and kicking and thinking.

I started there in the fall of ’45, actually, so this

makes forty-one years. My own thought about teaching composition is

pretty much that of my last teacher, Béla Bartók, with whom

I was able to work during his last year off and on. He took me on,

and as far as I know — at least it is said

— that I’m the only American student of composition of his.

It’s probably true. I knew that he didn’t teach composition, but had

always taught piano. That was why I wrote a short letter to him in

the summer of ’44, and told him that I understood that he didn’t teach composition.

I rather imagined that I understood why, but I thought — and this is the

sentence that apparently did it — that it might be possible for somebody

to learn something from someone who thought he couldn’t teach it! [Both

laugh] That apparently intrigued him, and so we worked that year.

In fact I’m inclined to think that he had rather the right idea, because

people who are not talented you can’t do very much with, except to show them

some elements of the craft, which almost anybody can learn, and lots of very

intelligent people do. And those who have a great deal of talent —

or creative talent, as it’s called, or ideas — can learn the craft and then

will probably do pretty much what they would do without anybody looking over

the shoulder. I’m inclined to believe that it’s possible to show somebody

where an abyss is that he’s headed for — the abyss being some

sort of compositional problem — but that only the untalented

won’t try the abyss. The talented ones will fall in and find their

own way out of it. I’m not quite sure that teaching composition is

like teaching French, or physics, or whatever.

JB:

I rather imagine that teaching composition hasn’t changed very much, at least

where I am. I learned a good deal about how to go about it from Otto Luening, whom I was

assisting at first, and who’s still very much alive and kicking and thinking.

I started there in the fall of ’45, actually, so this

makes forty-one years. My own thought about teaching composition is

pretty much that of my last teacher, Béla Bartók, with whom

I was able to work during his last year off and on. He took me on,

and as far as I know — at least it is said

— that I’m the only American student of composition of his.

It’s probably true. I knew that he didn’t teach composition, but had

always taught piano. That was why I wrote a short letter to him in

the summer of ’44, and told him that I understood that he didn’t teach composition.

I rather imagined that I understood why, but I thought — and this is the

sentence that apparently did it — that it might be possible for somebody

to learn something from someone who thought he couldn’t teach it! [Both

laugh] That apparently intrigued him, and so we worked that year.

In fact I’m inclined to think that he had rather the right idea, because

people who are not talented you can’t do very much with, except to show them

some elements of the craft, which almost anybody can learn, and lots of very

intelligent people do. And those who have a great deal of talent —

or creative talent, as it’s called, or ideas — can learn the craft and then

will probably do pretty much what they would do without anybody looking over

the shoulder. I’m inclined to believe that it’s possible to show somebody

where an abyss is that he’s headed for — the abyss being some

sort of compositional problem — but that only the untalented

won’t try the abyss. The talented ones will fall in and find their

own way out of it. I’m not quite sure that teaching composition is

like teaching French, or physics, or whatever. BD:

You seem to be one of the few composers who is also a major professor who

is performed widely. Does that surprise you at all?

BD:

You seem to be one of the few composers who is also a major professor who

is performed widely. Does that surprise you at all?

JB: That’s also a difficult question to answer

because painters, writers, composers like to think that they are doing it

only for themselves, and in the long run that’s not quite true. To

speak of composers, they write for listeners who are like themselves, and

hope to find a great many of them, and generally don’t find as many as they’d

like. But others then have to be considered. One doesn’t just

write down anything he feels like writing for performers, because it might

be that one felt like writing something the performers can’t do either individually

or in ensemble or under a conductor. So there is a compromise, or

rather it’s not so much a compromise as doing what’s possible to do.

It’s also true that one has different audiences in mind. If one writes

a string quartet, for example, there need be only four people besides the

composer, who himself might be one of the performers, that bring it to life.

Whereas if one’s doing it for an opera house, there will be an audience

of anywhere from a thousand, perhaps a few less, to three or four thousand.

Most of those are not musicians and have come for a theatrical performance.

So that music which might work for four people is not going to work for four

thousand, not to speak of the difference in playing with string quartets

and having an orchestra, a conductor, and people on stage.

JB: That’s also a difficult question to answer

because painters, writers, composers like to think that they are doing it

only for themselves, and in the long run that’s not quite true. To

speak of composers, they write for listeners who are like themselves, and

hope to find a great many of them, and generally don’t find as many as they’d

like. But others then have to be considered. One doesn’t just

write down anything he feels like writing for performers, because it might

be that one felt like writing something the performers can’t do either individually

or in ensemble or under a conductor. So there is a compromise, or

rather it’s not so much a compromise as doing what’s possible to do.

It’s also true that one has different audiences in mind. If one writes

a string quartet, for example, there need be only four people besides the

composer, who himself might be one of the performers, that bring it to life.

Whereas if one’s doing it for an opera house, there will be an audience

of anywhere from a thousand, perhaps a few less, to three or four thousand.

Most of those are not musicians and have come for a theatrical performance.

So that music which might work for four people is not going to work for four

thousand, not to speak of the difference in playing with string quartets

and having an orchestra, a conductor, and people on stage. BD:

I understand that you wrote the opera without any

hope of it being performed.

BD:

I understand that you wrote the opera without any

hope of it being performed.

JB: I might approve or I might not, but generally

speaking they always ask, and then generally I approve or find some other

way of doing it. The difference is that the composer is somebody who

is accustomed to making things up and the performers aren’t, so they are

likely to change things in the direction of what they’ve already heard,

which is somebody else’s music. Often it’s occurred that they’d ask

me to consider making some sort change, “What about so-and-so?” and I’d

say, “Well, sure. Let’s see what we can do,” and then fuss around with

their solution, use it, or find out something which seems to be more in style

with what I’m doing.

JB: I might approve or I might not, but generally

speaking they always ask, and then generally I approve or find some other

way of doing it. The difference is that the composer is somebody who

is accustomed to making things up and the performers aren’t, so they are

likely to change things in the direction of what they’ve already heard,

which is somebody else’s music. Often it’s occurred that they’d ask

me to consider making some sort change, “What about so-and-so?” and I’d

say, “Well, sure. Let’s see what we can do,” and then fuss around with

their solution, use it, or find out something which seems to be more in style

with what I’m doing.

BD:

Your whole outlook seems to be much more tolerant than many composers either

of the past or the present.

BD:

Your whole outlook seems to be much more tolerant than many composers either

of the past or the present. BD:

The date on the original article was 1963, and this is 1986, so that’s over

twenty years ago.

BD:

The date on the original article was 1963, and this is 1986, so that’s over

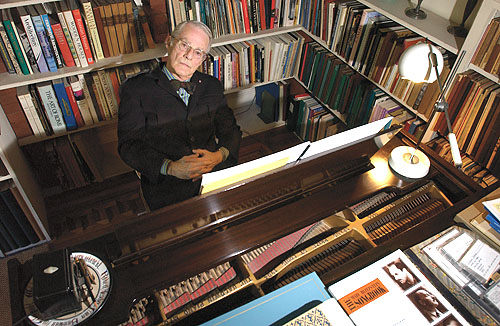

twenty years ago.Vis-à-vis the photo at right, six opera composers were honored at the 1998 National Opera Association Convention

in Washington D.C., with Lifetime Achievement Awards. From left in the photo are Opera Music Theater

International's General Director, and Chairman of the Convention James K. McCully, Jr., with composers Robert

Ward, Kirke Mechem, Thea Musgrave, Jack Beeson, Seymour Barab (partially hidden), and Carlisle Floyd. Others

who received the award but did not attend the ceremony were Ruby Mercer, Rudolph Fellner, Ruth Martin, Mary

Elaine Wallace, and Robert Gay.

BD:

Would now be a good time to do an entirely new production, or even bring back

the old production of My Heart’s in the

Highlands?

BD:

Would now be a good time to do an entirely new production, or even bring back

the old production of My Heart’s in the

Highlands? JB: On the whole, yes. I’m not a great fan

of recordings actually, and I always have some doubts about whether the

pieces that are intended for the theater actually work in the purely musical

fashion, but after all, I’m no worse off, I suppose, than other composers

of operas which are intended to be seen. Maybe it will become, in

another context, that operas ought to be seen and not heard. [Both

laugh] But I’m delighted that they’re recorded and available.

I’m mostly pleased with the recordings, some of which were done under very

much less than ideal circumstances. Almost no contemporary operas,

and certainly I would say no American operas, have been done in circumstances

even remotely comparable to the kind of circumstances that bring out not-so-good

works of the past. A performance of any standard in the opera repertory

of recordings is done under optimum, luxurious circumstances, compared to

the manner in which operas by American composers get done.

JB: On the whole, yes. I’m not a great fan

of recordings actually, and I always have some doubts about whether the

pieces that are intended for the theater actually work in the purely musical

fashion, but after all, I’m no worse off, I suppose, than other composers

of operas which are intended to be seen. Maybe it will become, in

another context, that operas ought to be seen and not heard. [Both

laugh] But I’m delighted that they’re recorded and available.

I’m mostly pleased with the recordings, some of which were done under very

much less than ideal circumstances. Almost no contemporary operas,

and certainly I would say no American operas, have been done in circumstances

even remotely comparable to the kind of circumstances that bring out not-so-good

works of the past. A performance of any standard in the opera repertory

of recordings is done under optimum, luxurious circumstances, compared to

the manner in which operas by American composers get done.

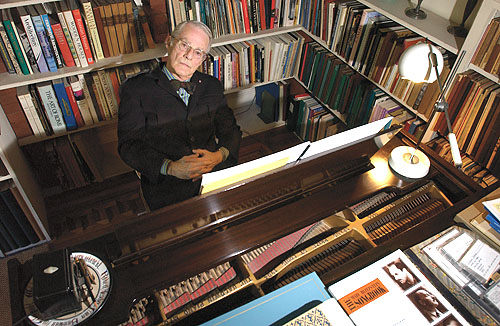

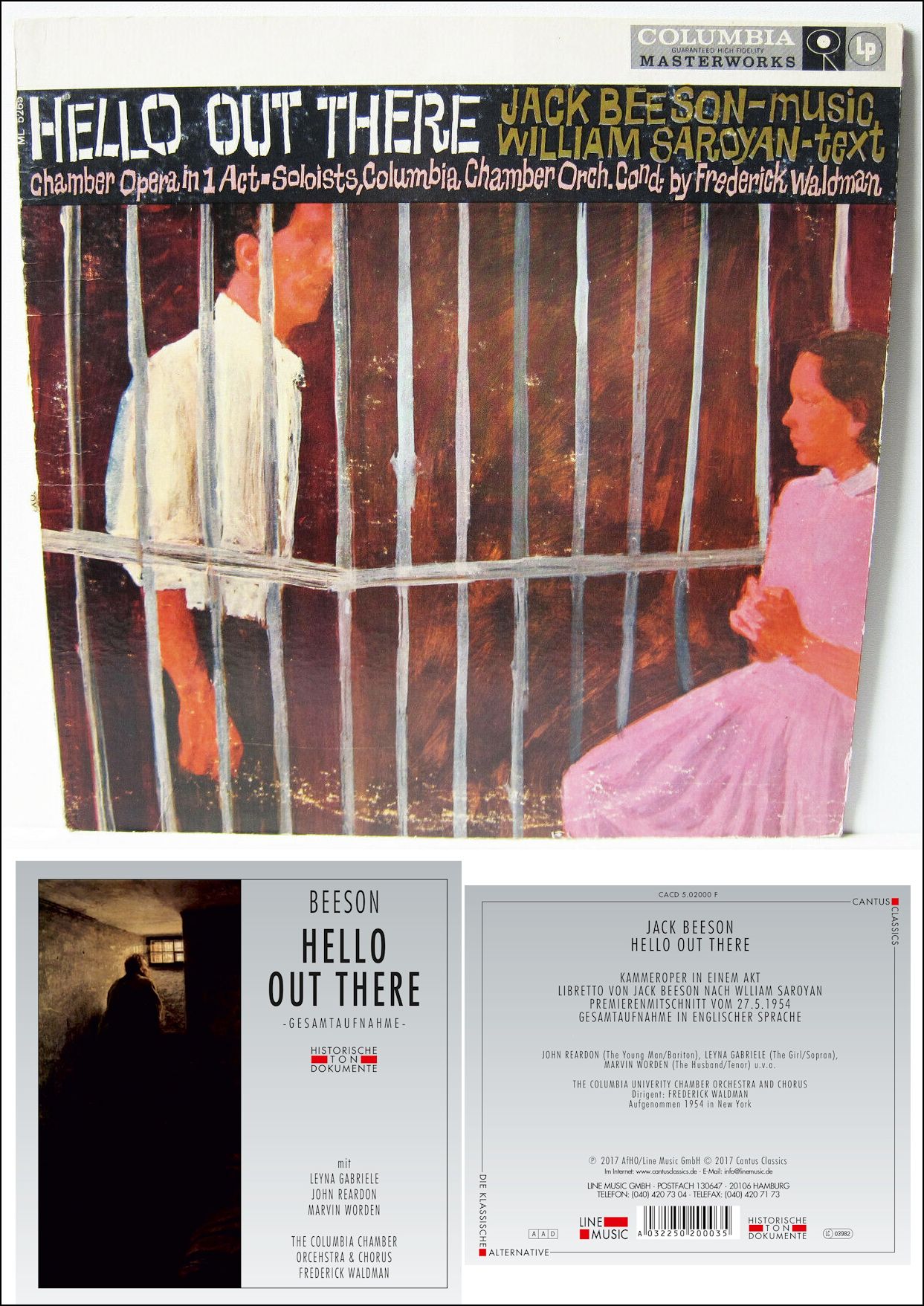

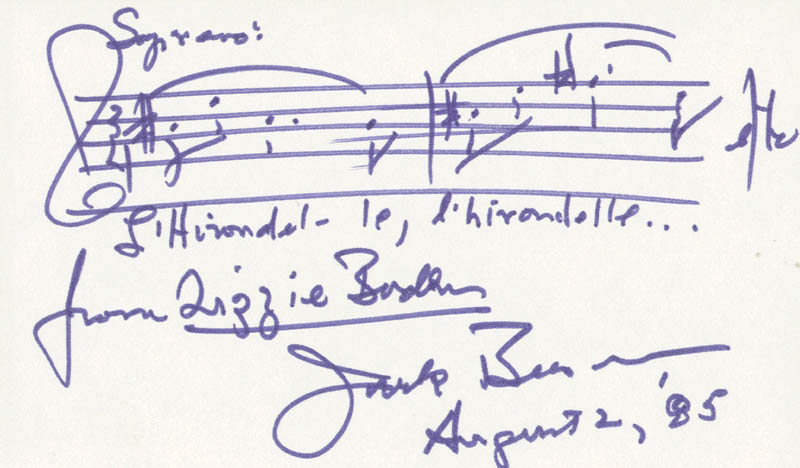

| Jack

Beeson was born and received his early education in Muncie, Indiana. He studied

composition at the Eastman School, completing Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees.

Upon winning the Prix de Rome and a Fulbright Fellowship Beeson lived in

Rome from 1948 through 1950 where he completed his first opera, Jonah,

based on a play by Paul Goodman. Beeson then adapted a work by the well-known

American playwright, William Saroyan, for Hello Out There, a one

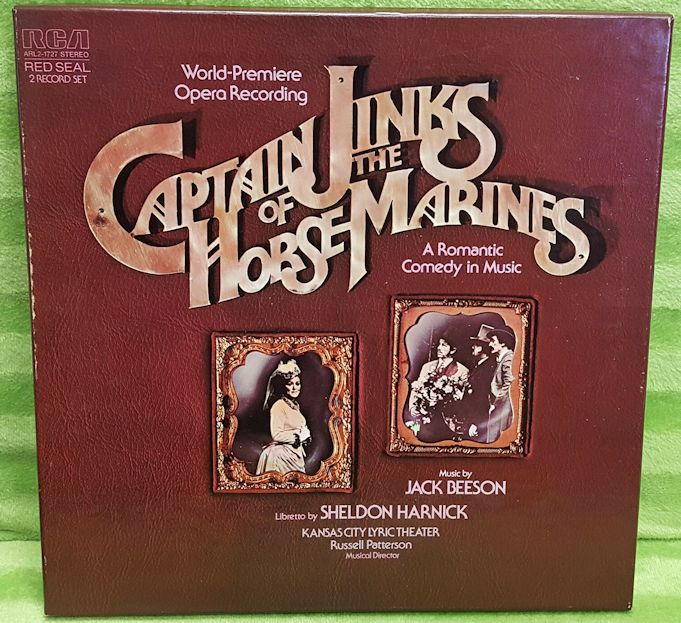

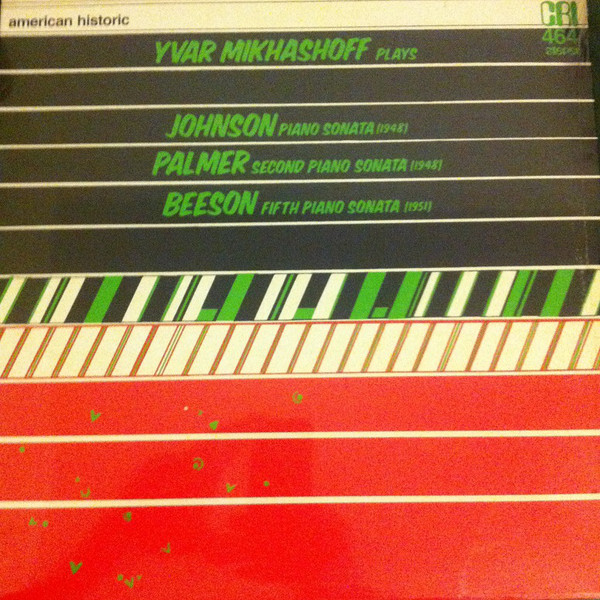

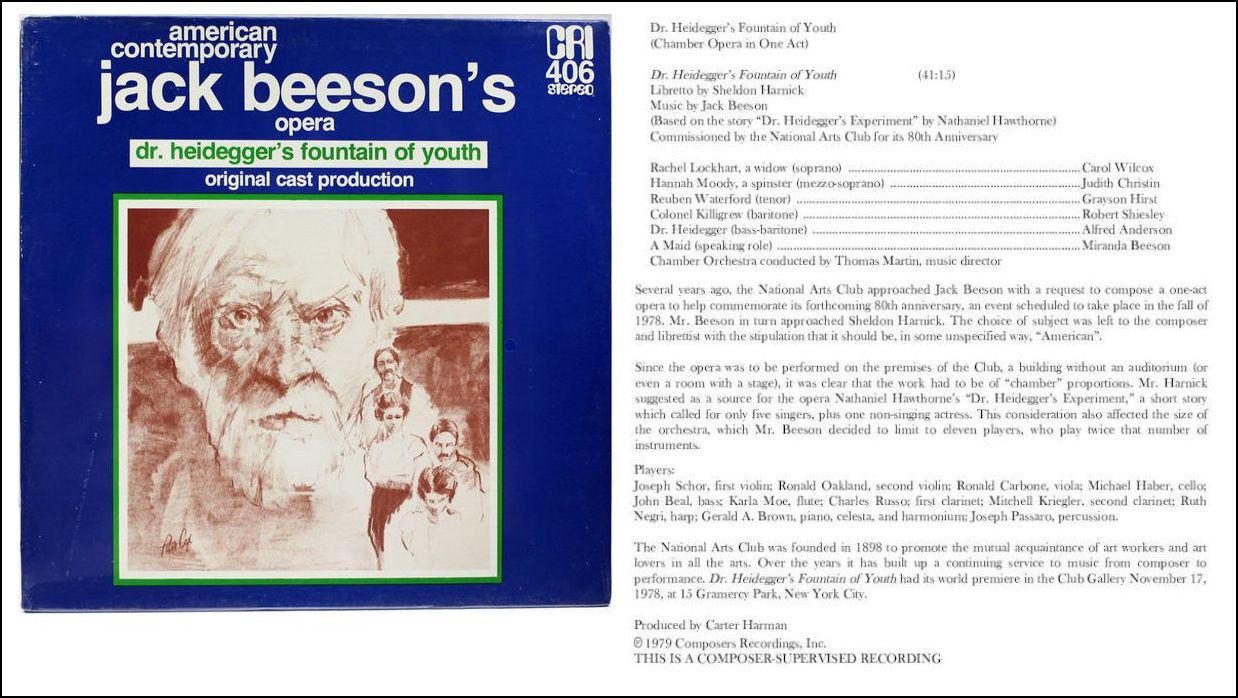

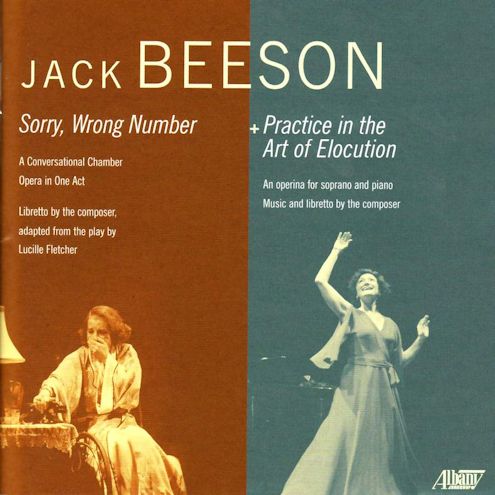

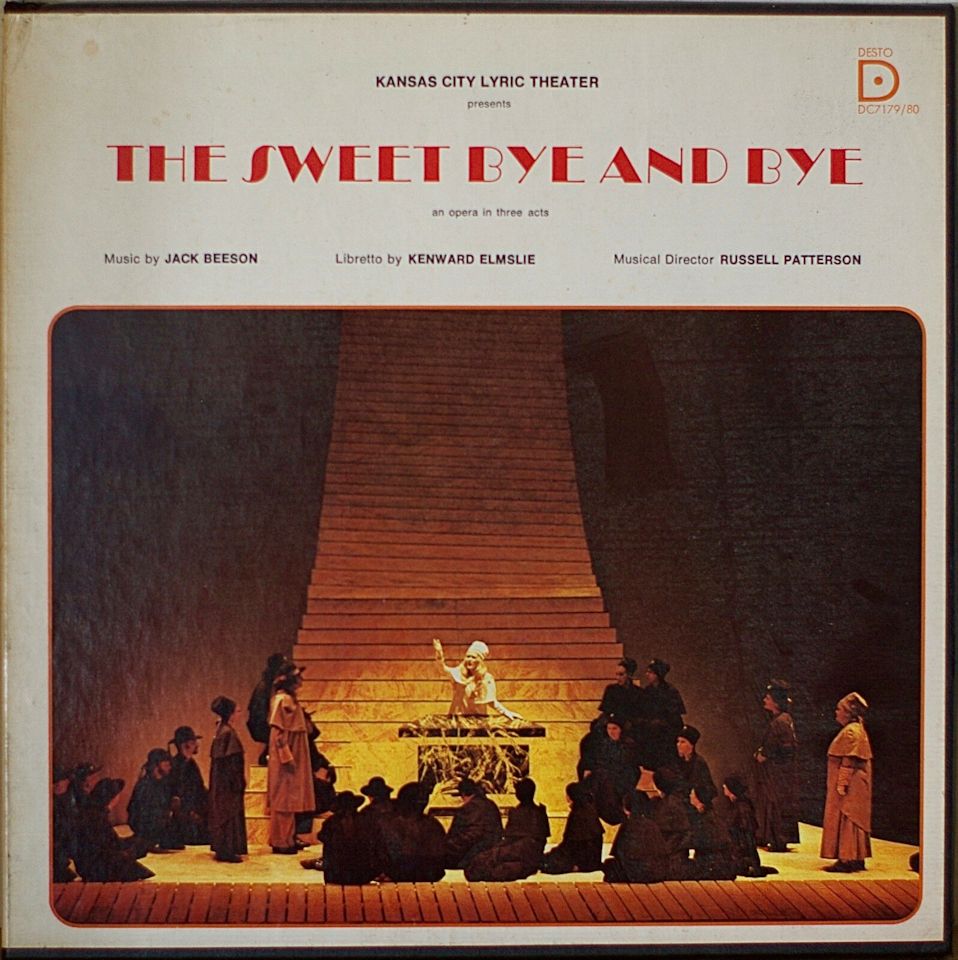

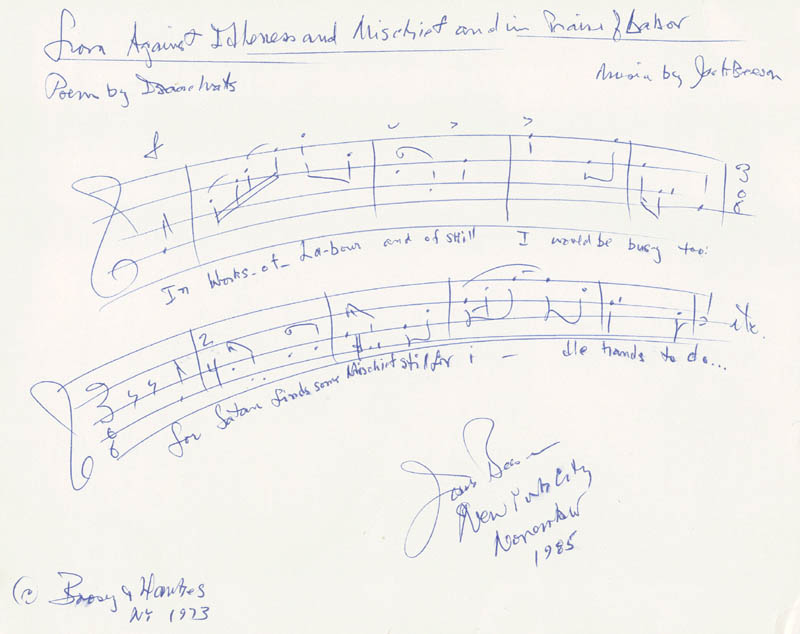

act chamber opera produced by the Columbia Theater Associates in 1954. The Sweet Bye and Bye, with a libretto by Kenward Elmslie, was produced by the Juilliard Opera Theater in 1957. It concerns the leader of a fundamentalist sect and her conflict between duty and love. The central character, Sister Rose Ora, resembles famous religious leader Aimee Semple MacPherson. The score includes marching songs, hymns, chants, and dances, as well as memorable arias and ensembles. Beeson’s next opera, Lizzie Borden, again based on an American subject, was commissioned by the Ford Foundation for the New York City Opera. Lizzie Borden tells the familiar story with less emphasis on the ax murders than on "the psychological climate that made them inevitable", according to critic Robert Sherman. In American Opera Librettos, Andrew H. Drummond writes, "This opera has an obvious dramatic effectiveness in which a clear and direct development with tightly drawn characterization leads to a powerful climax." New York City Opera premiered Lizzie Borden in 1965, and it was produced for television by the National Educational Television Network in 1967 using the original cast. A new NYCO production opened in March 1999 and was telecasted by PBS. With 1975’s Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, Beeson found a gifted collaborator in Broadway lyricist (and also composer and translator) Sheldon Harnick. Several years later, the two hit on a possible subject, Clyde Fitch’s romantic comedy about a wager on the virtue of a prima donna which leads to true love. Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines was premiered by the Lyric Opera of Kansas City in 1975, and featured in the catalog accompanying Opera America’s Composer-Librettist Showcase in Toronto. The next Beeson-Harnick work, Dr. Heidegger’s Fountain of Youth, a short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne, was produced by the National Arts Club in New York in 1978. Beeson and Harnick then collaborated on Cyrano, "freely adapted" from the Rostand play, according to Beeson. Cyrano was given its premiere in 1994 by Theater Hagen in Germany. Sorry Wrong Number (based on the play by Louise Fletcher) and Practice in the Art of Elocution were premiered in New York in 1999, both with librettos by the composer. In addition to these 10 operas, Beeson has composed 120 works in various media. In addition to his work as a composer, Beeson also had a distinguished career as a teacher at Columbia University where he was the MacDowell Professor Emeritus of Music, a chair previously held by Douglas Moore. Jack Beeson's music is published exclusively by Boosey & Hawkes. |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on August 2, 1986.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1987, 1991, 1996 and

1999. An unedited copy of the audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.