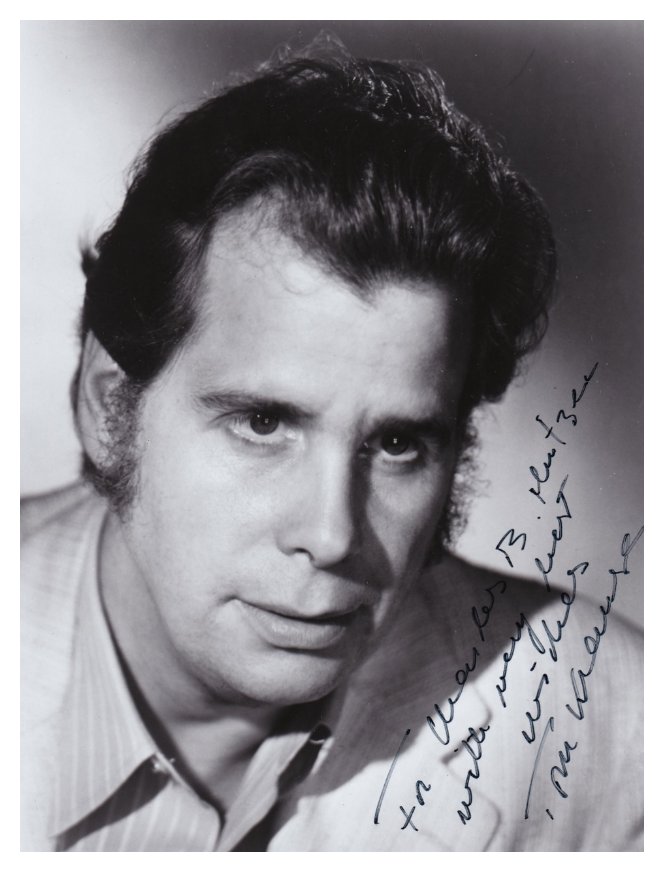

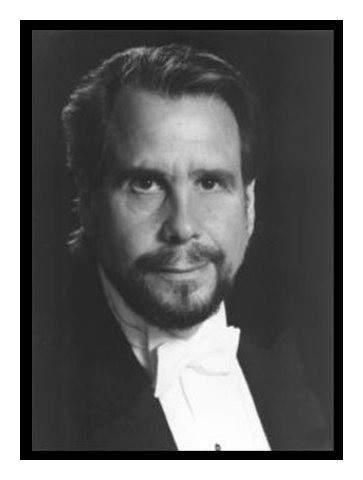

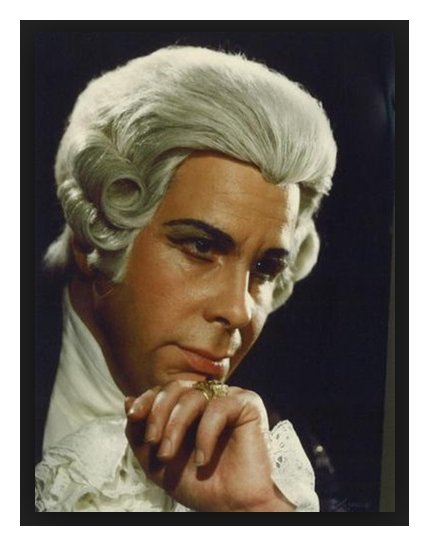

Equally successful in the fields of

opera, recital, oratorio and recording, Finnish baritone Tom Krause is

internationally recognized as one of the greatest vocal artists today. Equally successful in the fields of

opera, recital, oratorio and recording, Finnish baritone Tom Krause is

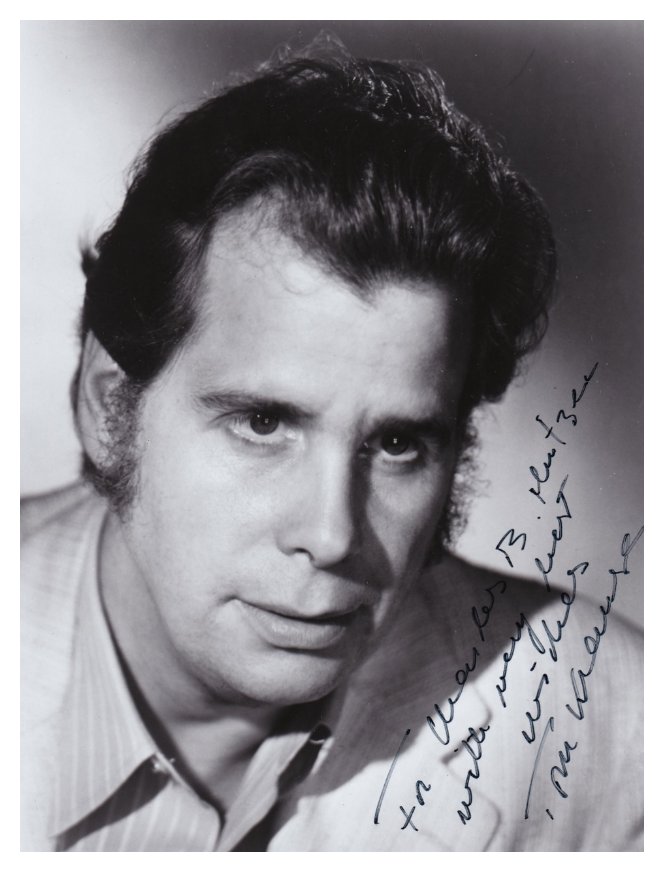

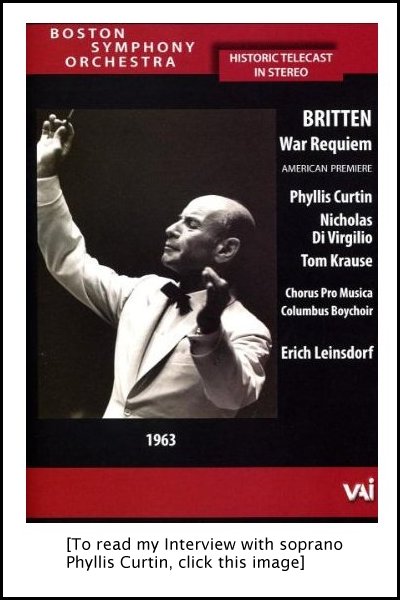

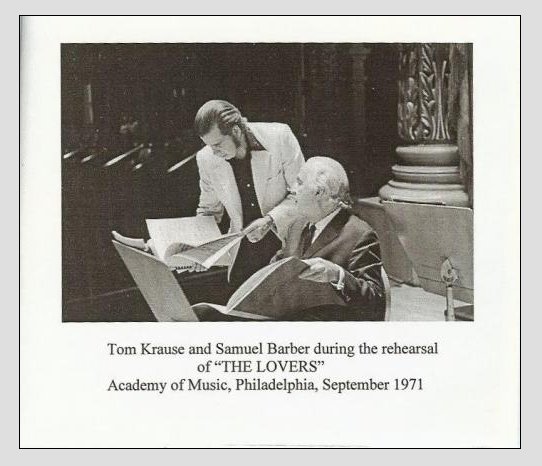

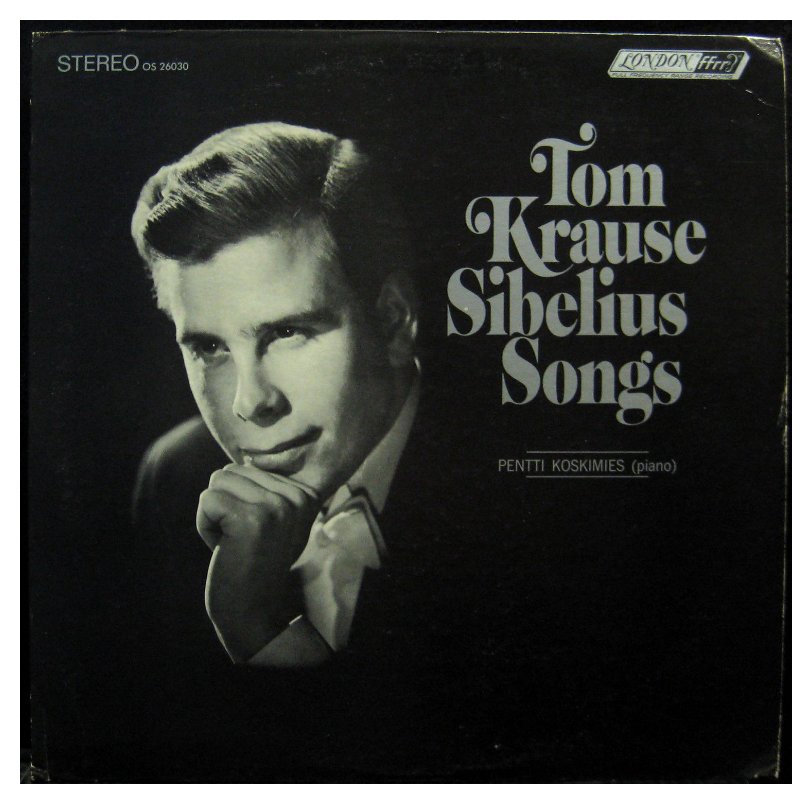

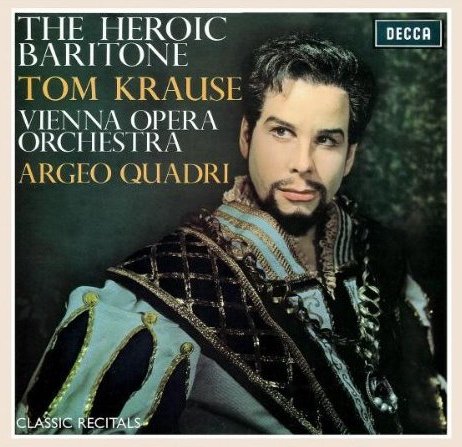

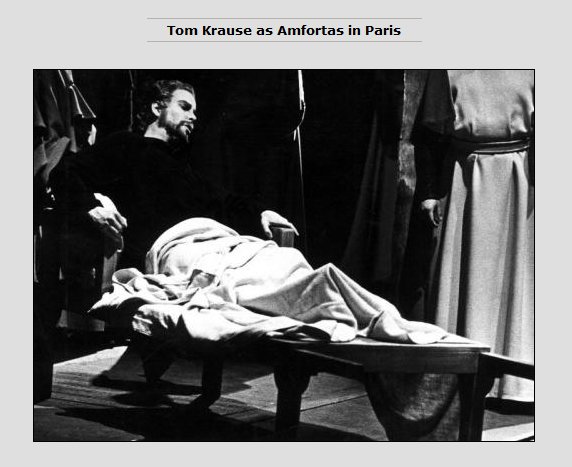

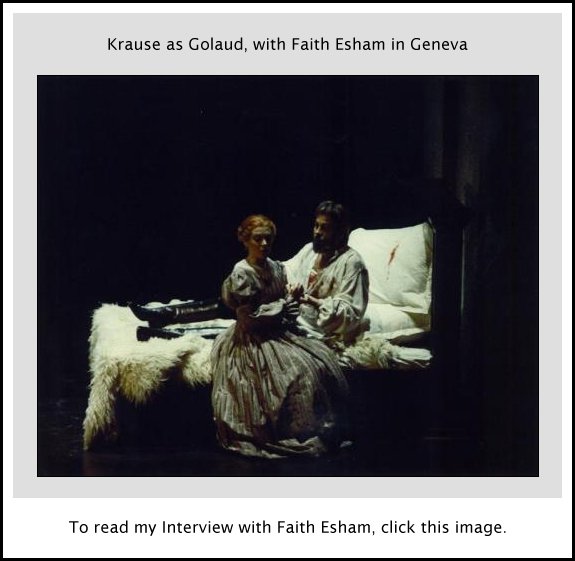

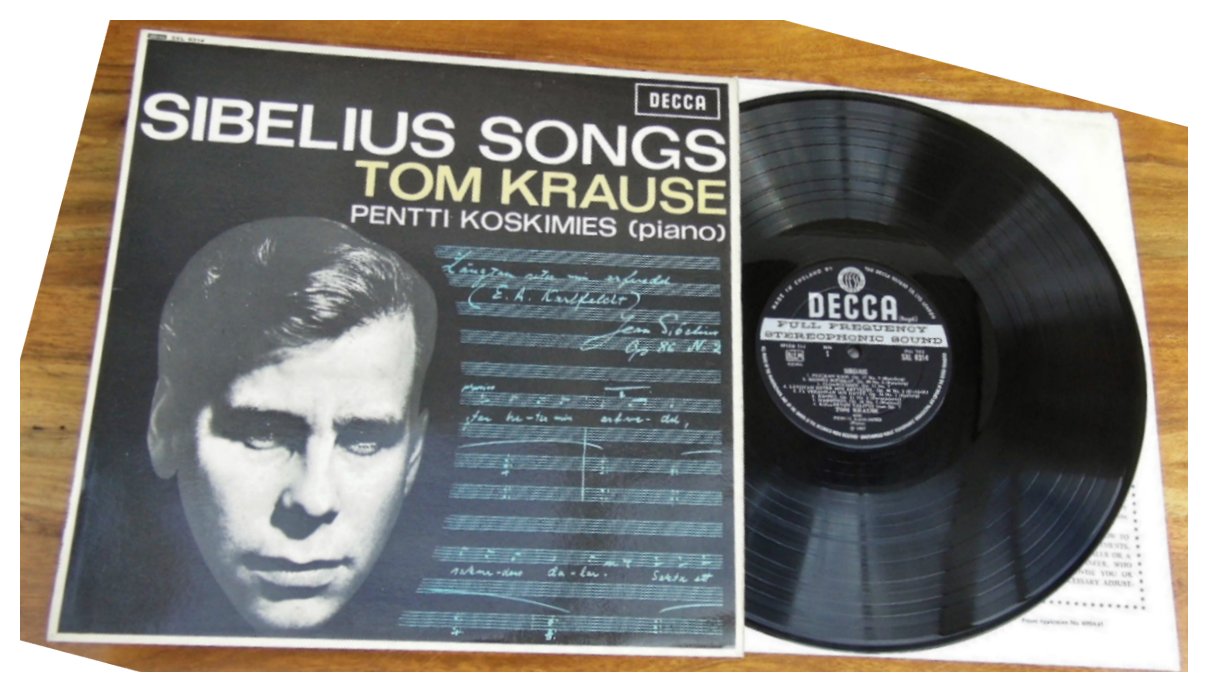

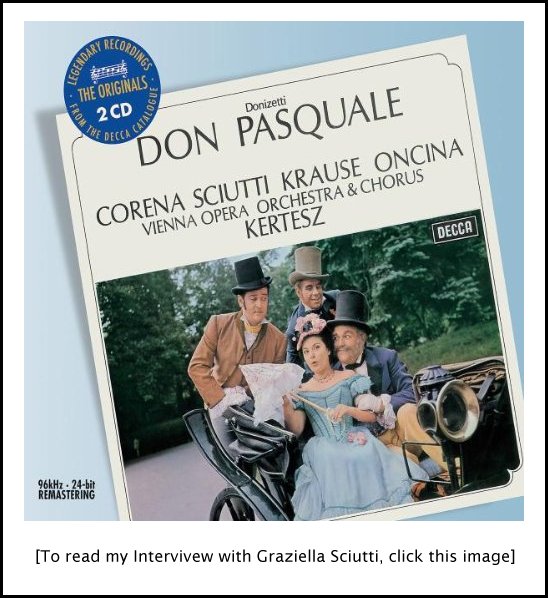

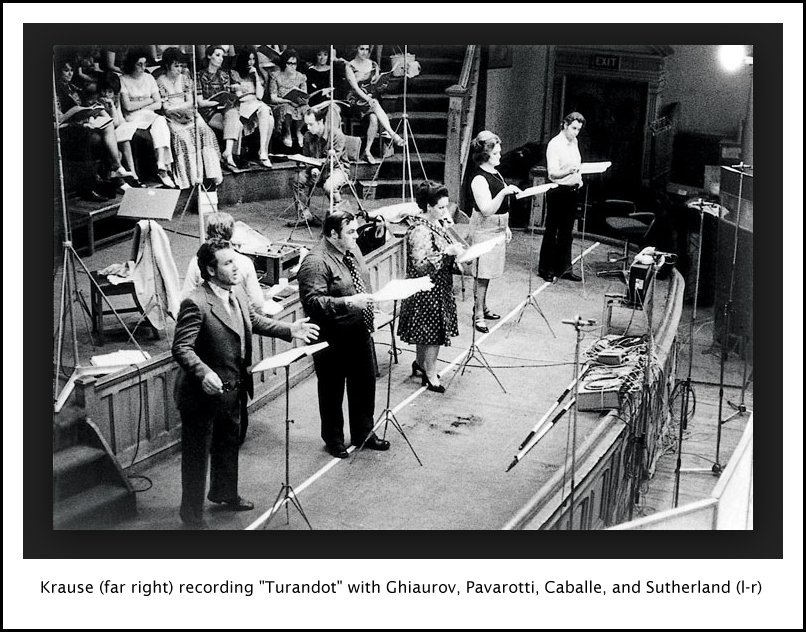

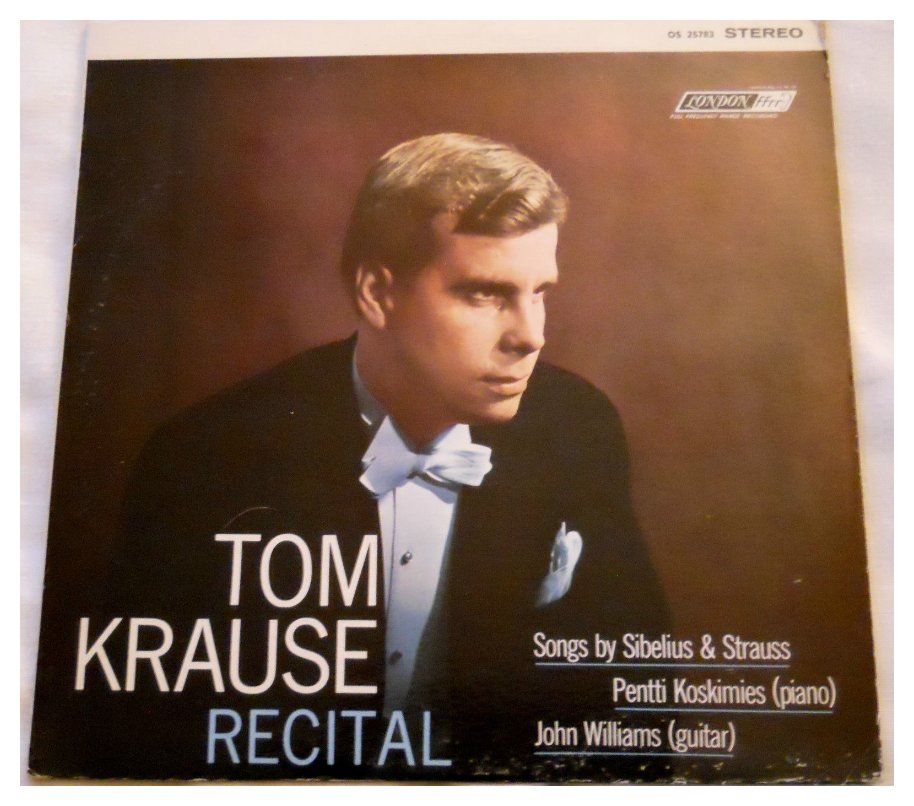

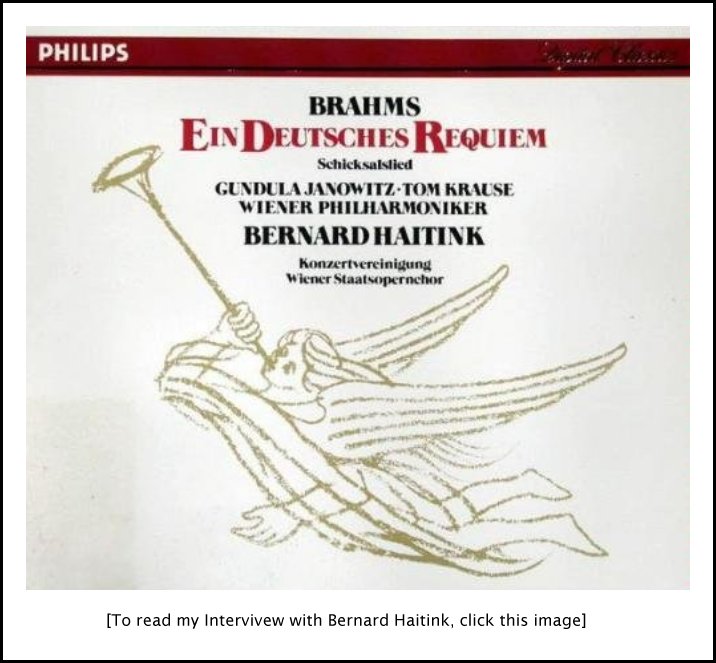

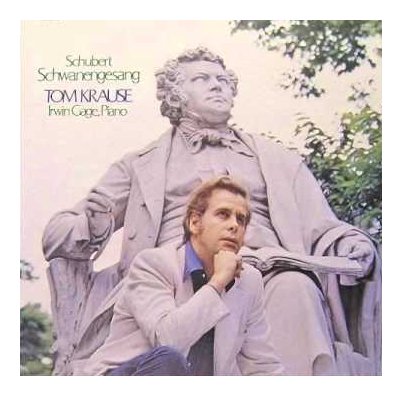

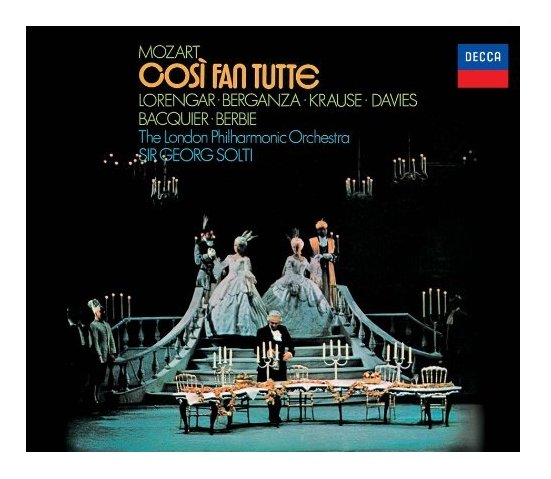

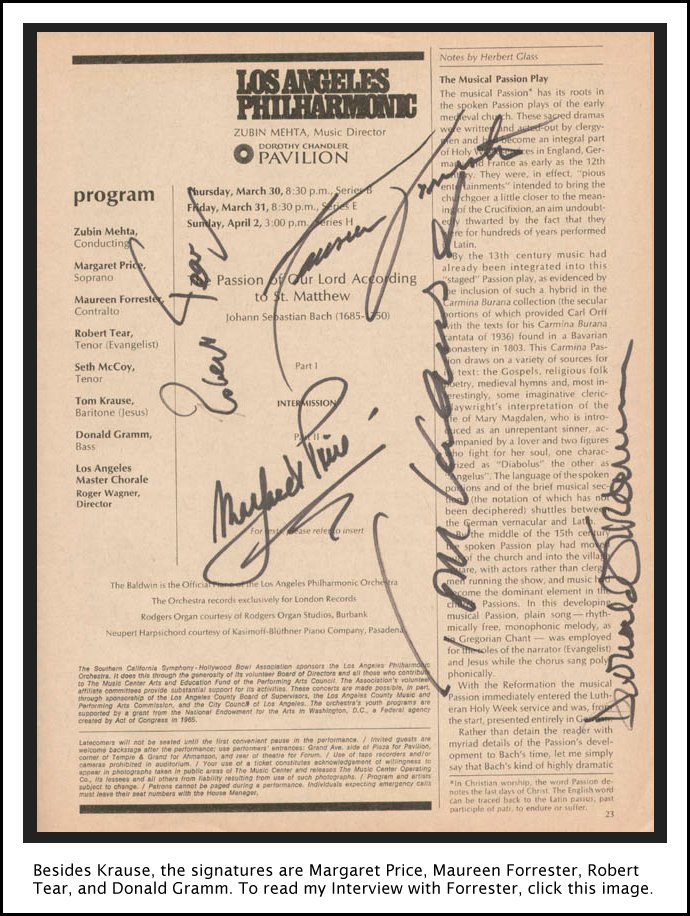

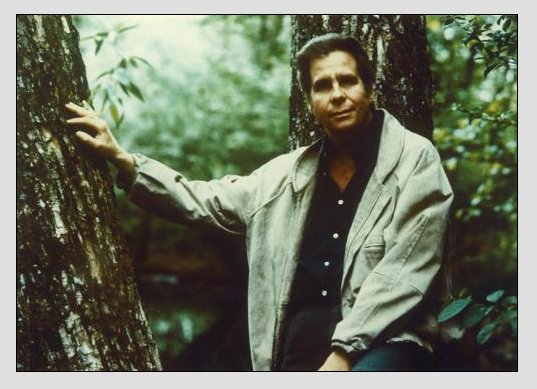

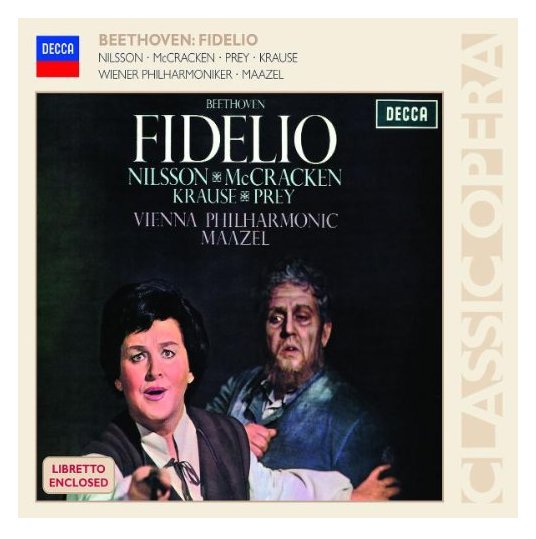

internationally recognized as one of the greatest vocal artists today.He is fluent in seven languages: English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Swedish and Finnish. During a career spanning over fifty roles in the Italian, German, French, English, Finnish, Czech, Russian, and Swedish repertory including the Baroque, Classical, Romantic and Modern, Mr. Krause has performed in most of the great opera houses of the world. He has appeared in leading roles with Milan's La Scala; Teatro Colon, Buenos Aires; Berlin Opera; Vienna State Opera; Munich State Opera; Paris Operas (theatres Garnier and Bastille); Bruxelles Opera Monnaie; Finnish National Opera; Rome Opera; Naples' San Carlo Opera; Barcelona’s Teatro Liceo; Geneva Opera; Metropolitan Opera House; Lyric Opera of Chicago; San Francisco Opera and Houston Grand Opera, as well as with the festivals of Bayreuth, Salzburg, Edinburgh, Glyndebourne, Savonlinna, Tanglewood, etc. A frequent guest soloist in concert, the baritone has been heard regularly with the Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Boston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Montreal Symphony, Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, Amsterdam Concertgebow, and others. Mr. Krause has regularly shared the stage and recorded with such great singers as Placido Domingo, Luciano Pavarotti, Jessye Norman, Kiri Te Kanawa, Joan Sutherland, Birgit Nilsson, Marilyn Horne, Margeret Price, Teresa Berganza, and Nicolai Gedda, as well as under brilliant conductors of our time including Bernstein, Stravinsky, Solti, Von Karajan, Mehta, Ormandy, Shaw, Ozawa, Rostropovich, Eschenbach, Conlon, Salonen, Harnoncourt and Giulini. He has worked with stage directors such as Ponnelle, Strehler, Faggioni, Sellars, Dresen, Everding, Lieberman, Menotti, and Chereau. In 1963, after having performed the Britten War Requiem conducted by the composer, Benjamin Britten chose Tom Krause to sing the American premiere at the Tanglewood Summer Festival with the Boston Symphony, conducted by Erich Leinsdorf. [See photo of video recording at right.] This led to several concerts in Boston and New York City, in big concert tours throughout the USA and Canada and in 1967, to his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York as the Count in The Marriage of Figaro in a cast including Cesare Siepi, Mirella Freni, Teresa Berganza and Pilar Lorengar. [See autographed program below.]  [Besides Krause, the signatures are Cesare Siepi, Pilar Lorengar, and Mirella Freni] In 1968, Mr. Krause was invited by Herbert von Karajan to replace the indisposed Nicolai Ghiaurov as Don Giovanni at the Salzburg Music Festival. This led to two further performances of Don Giovanni that summer, three more in 1969, and the role of Guglielmo in a new production of Cosi Fan Tutte with Seiji Ozawa and J.P. Ponnelle that same year. Mr. Krause performed regularly at the Salzburg Music Festival for 20 years, appearing in opera, orchestra concerts and recitals. In 1969, Mr. Krause performed and recorded Elijah by Mendelssohn with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. Then in 1970 Ormandy chose Krause for the American Premiere of the 13th Symphony by Shostakovich, and in 1971 Samuel Barber composed The Lovers, the oratorio for baritone solo and choir, for Tom Krause. [See photo below.]  A renowned recital artist, he has given countless solo recitals in the most important cities in the U.S.A., Canada, Europe and Japan. He has also appeared in numerous television and feature films. As one of the most prolific recording artists of our era, he can be heard in over 100 recordings. His works and recordings have awarded him numerous distinctions and prizes during his long career. His recordings of Bach with Munchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra were awarded the Bach prize. His recording of Carmen with Marilyn Horne under Leonard Bernstein received a certificate for the best opera recording of 1973 by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. His recording of the complete Sibelius songs received the Edison Prize, the Deutsche Schallplatten Prize and the Grammaphone Prize, among others.  During the 1980's, Mr. Krause started giving master classes in the U.S.A. and Europe. From 1989 to 1990 he was guest professor at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, and from 1994 to 2001, a full professor at the Music Academy in Hamburg. In 2002, he added a full professorship at the Queen Sofia School of Music, Madrid, Spain, where he chairs the vocal department. In the same year he left the stage of concert and opera. His last important opera appearance was as Moses in Schoenberg’s Moses and Aron at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo. He had started performing professionally as a popular singer in 1952, and his debut as a classical singer was in 1958 with an extremely successful recital in Helsinki. Because of his enormous experience in all the fields of classical music and his interest in passing on his legacy of great singing, Mr. Krause is in great demand for master classes around the world and is highly regarded as a juror in the most important international singing competitions. He has frequently been head of the Jury or Jury Member at the most prestigious International Singing competitions such as Mobil Song Quest, Auckland; the Queen Sonja International Singing Competition, Oslo; the Mirjam Helin International Singing Competition, Helsinki; Queen Elizabeth Singing Competition, Brussels; the ARD Competition, Munich; the Tschaikowski Singing Competition, Moscow; International Competition of the Art of Lied, Stuttgart; the Singer of the World Competition, Cardiff; the Montreal International Singing Competition, Montreal, Canada; the Moniuszko Competition, Warsaw; etc. Mr. Krause has regularly given master classes at the Academy of Vocal Arts and the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, PA; the Sibelius Academy, Helsinki; Villecroze Academie Musicale, France; Chapelle Musicale Reine Elisabeth, Brussels; Mozarteum Summer Academy, Salzburg; Encuentro Musical, Santander; the Festival Music Academy, Savonlinna; Voksenåsen Summer Music Academy, Oslo; Kusastsu Music Festival, Kusatsu, Japan; etc. He has also given master classes at the San Francisco Opera, California; the Florida Grand Opera, Miami, Florida; Schleswig-Holstein Festival; the Fifth International Congress of Voice Teachers, Helsinki; Kunitachi School of Music, Tokyo; the Nagoya School of Music, Nagoya; Poland; Portugal, Cairo, Ankara, etc. In 1990, the Finnish State awarded Mr. Krause with the Order of the Finnish Lion - the highest award for cultural personalities in Finland. He was also given the title Kammersaenger in Hamburg for his achievements there. In recognition of his brilliant artistic contribution to his native Finland, the Helsinki University awarded Mr. Krause the title of Doctor of Music Honoris Causa. Recently he was given the Sibelius medal by the Sibelius Academy, honoring his work in music in Finland and around the world. -- Biography slightly

edited from his official website.

-- Photos and links added for this website presentation. -- Links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

Tom Krause: Oh, it

depends on the occasion, I would

say. But I’m really a bass-baritone, I think.

Tom Krause: Oh, it

depends on the occasion, I would

say. But I’m really a bass-baritone, I think.  BD: So he’s down at

the bottom of the abyss?

BD: So he’s down at

the bottom of the abyss? TK: I don’t

know. If the

sexual act would be banned in harmony with the higher spirits or the

higher state, it would be done so that the releasing factor is

love, and this is a complete act of love on all the different

levels. It probably would be great, but if there are certain

elements of impurity or perversion involved, then the danger is very

great. On the other hand you have Parsifal who

is ‘the pure fool’ they call him. He’s the man who hasn’t

accepted the world at all. He

has stayed in this state of purity, of innocence, although he’s not

quite aware of it at the beginning. But at the

end he is actually united with the Divine Principle.

TK: I don’t

know. If the

sexual act would be banned in harmony with the higher spirits or the

higher state, it would be done so that the releasing factor is

love, and this is a complete act of love on all the different

levels. It probably would be great, but if there are certain

elements of impurity or perversion involved, then the danger is very

great. On the other hand you have Parsifal who

is ‘the pure fool’ they call him. He’s the man who hasn’t

accepted the world at all. He

has stayed in this state of purity, of innocence, although he’s not

quite aware of it at the beginning. But at the

end he is actually united with the Divine Principle.

BD: Do you find

that this takes a toll on you and also

on your other colleagues?

BD: Do you find

that this takes a toll on you and also

on your other colleagues? BD: It’s interesting

because each singer describes it

a little bit differently. They all get to the same point, but

they come from different roads. Some singers always think of

‘singing

into the mask’, while others focus out here [indicates an arm’s

length in front of the body]. Others think of putting it on the

back wall gently.

BD: It’s interesting

because each singer describes it

a little bit differently. They all get to the same point, but

they come from different roads. Some singers always think of

‘singing

into the mask’, while others focus out here [indicates an arm’s

length in front of the body]. Others think of putting it on the

back wall gently. TK: Yes, it doesn’t

work. They can’t do it. I

have a central manager in Paris, but he needs somebody. He

can’t know what’s going on in Austria and in Belgium and in Holland,

in Germany, Scandinavia, Spain. He can’t be on the

scene; he can’t be there. And when something happens you need

somebody who’s there to say, “Take him, he’s the best!” Of course

if you’re the manager of

Pavarotti, you don’t have that problem! [Both laugh]

TK: Yes, it doesn’t

work. They can’t do it. I

have a central manager in Paris, but he needs somebody. He

can’t know what’s going on in Austria and in Belgium and in Holland,

in Germany, Scandinavia, Spain. He can’t be on the

scene; he can’t be there. And when something happens you need

somebody who’s there to say, “Take him, he’s the best!” Of course

if you’re the manager of

Pavarotti, you don’t have that problem! [Both laugh]

BD: Would

someone who hasn’t been to a

concert for many years, or perhaps never been to a concert, be prepared

enough to accept it and

understand it?

BD: Would

someone who hasn’t been to a

concert for many years, or perhaps never been to a concert, be prepared

enough to accept it and

understand it? TK: Of course!

We had a production of Madame

Butterfly in Paris by a certain man

called Lavelli, and that was his

approach. It’s possible he listened to the music and he clicked

off to these particular nightmare-ish things that then came

out. God knows it’s possible that he listened to the

music, but I really felt that he was using Puccini’s Madame

Butterfly as an excuse for being allowed to put certain things

on

stage. Certainly the ambience, the feeling

of the whole thing was such that the music just died. Everything

was in a cold white light. The whole

stage was covered with huge pebbles of cork, which very effectively

absorbed all the sound. He brought down a screen on the top of

the stage on order to have a cinemascope effect. It was very low,

and from the balcony you

couldn’t see most of the stage. All the voices were way upstage

and very

effectively caught by this screen and reflected back onto stage.

They didn’t

go out.

TK: Of course!

We had a production of Madame

Butterfly in Paris by a certain man

called Lavelli, and that was his

approach. It’s possible he listened to the music and he clicked

off to these particular nightmare-ish things that then came

out. God knows it’s possible that he listened to the

music, but I really felt that he was using Puccini’s Madame

Butterfly as an excuse for being allowed to put certain things

on

stage. Certainly the ambience, the feeling

of the whole thing was such that the music just died. Everything

was in a cold white light. The whole

stage was covered with huge pebbles of cork, which very effectively

absorbed all the sound. He brought down a screen on the top of

the stage on order to have a cinemascope effect. It was very low,

and from the balcony you

couldn’t see most of the stage. All the voices were way upstage

and very

effectively caught by this screen and reflected back onto stage.

They didn’t

go out.  BD: [Gently

protesting] But it seems that you sing more Mozart than

Wagner.

BD: [Gently

protesting] But it seems that you sing more Mozart than

Wagner. TK: It’s

questionable. He seems

to be making overtly snide remarks, so there’s obviously an

attraction. Anyhow it’s much more

interesting if you do it that way. I think that they’re really

drawn. He suddenly sees her and says, “Wow! This

girl! I’ve seen

her all the time but I’ve never thought of her that way. But I’d

really like to go to bed with her!” It doesn’t stop him because

that’s his character. He

would say, “Oh, well, too bad for Ferrando! Tough!”

TK: It’s

questionable. He seems

to be making overtly snide remarks, so there’s obviously an

attraction. Anyhow it’s much more

interesting if you do it that way. I think that they’re really

drawn. He suddenly sees her and says, “Wow! This

girl! I’ve seen

her all the time but I’ve never thought of her that way. But I’d

really like to go to bed with her!” It doesn’t stop him because

that’s his character. He

would say, “Oh, well, too bad for Ferrando! Tough!” BD: Are Wolfram

and

Tannhäuser the same age?

BD: Are Wolfram

and

Tannhäuser the same age?  BD: At least you’re

good at it! Occasionally you get

someone who sings and is obsessed with it, and it’s really rather

painful.

BD: At least you’re

good at it! Occasionally you get

someone who sings and is obsessed with it, and it’s really rather

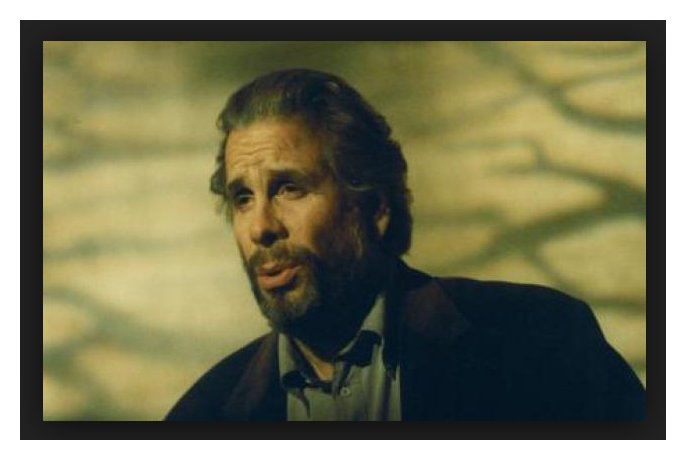

painful.  To read my Interview with James McCracken, click here. To read my Interview with Hermann Prey, click here. To read my Interview with Lorin Maazel, click here.  Krause in the film of Winterreise, D. 911 of Schubert |

This conversation was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on October 7, 1981. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1988, 1994, 1997 and 1999. The Wagner sections were transcribed and published in Wagner News in December, 1982. This full transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.