AD: Yes, because they’re not that living thing there.

It is a different creature altogether, and you can only experience it in

a theater.

AD: Yes, because they’re not that living thing there.

It is a different creature altogether, and you can only experience it in

a theater.

BD: But never to the detriment of the vocal lines.

BD: But never to the detriment of the vocal lines.|

Friday, May 26, 2006, Seattle Post-Intelligencer [Text only;

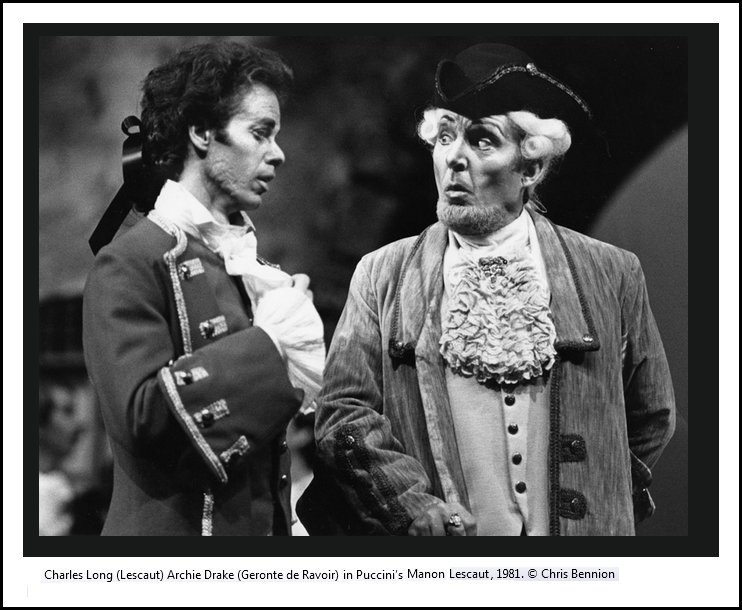

photo added for this website presentation] Archie Drake: 1925-2006: Singer known as 'soul of Seattle Opera' He was such a presence at Seattle Opera that he was widely known by just his first name -- Archie. But then a measure of recognition surely is earned when someone has sung 109 different roles for Seattle Opera in more than 1,000 performances over 39 seasons, which is why the opera's general director, Speight Jenkins, last year described Archie Drake as "the soul of Seattle Opera." The 81-year-old bass-baritone, with a familiar gaunt face reminiscent

of Don Quixote, was on stage once again Saturday night for the concluding

performance of "Macbeth," playing the minor role of "the Doctor." He sang

briefly in conversation with Lady Macbeth's lady in the opera's last act

[shown in photo below]. It turned

out to be the final performance of Drake's illustrious career.

Driven home afterward by an opera volunteer, Drake progressed up the stairs to the Queen Anne apartment where he had lived for 68 years. He was stricken with a massive coronary before he could open the front door. He was immediately discovered by a neighbor and rushed by medics to Harborview Medical Center. Drake never regained consciousness and died there Wednesday evening. Jenkins, traveling in Europe, learned of Drake's passing and said: "I have never known a man for whom I had more respect than Archie Drake. His work, his life, his whole being was concerned with giving. The world is a poorer place without him." Jenkins immediately began planning for a memorial celebration of Drake's life that the opera plans to host in late June. The singer's "fierce dedication to his art" and his "wry wit and warm heart" were saluted by Kelly Tweeddale, the opera's administrative director. Drake was born in 1925 in Great Yarmouth, England, and left home at 15 to follow his family's well-trodden path at sea. He served on merchant ships during World War II and afterward, but began his musical training during a posting in Vancouver, B.C. Drake later sang with the fabled Roger Wagner Chorale, traveling around the world once again, only this time for more than 500 performances on stage. In 1968, he made his operatic debut with the San Francisco Opera as Rambaldo in Puccini's "Rondine." That same year, a call from Glynn Ross, Seattle Opera's general

director, landed Drake two roles here in "Fidelio" -- Don Ferrando in the

German-language production, Rocco in the English. Drake signed on as a permanent

member of the company the following year and often sang in both productions

of various operas, those in the original language and those in English, sometimes

performing different roles on different nights.

Drake's main-stage roles for Seattle Opera included: Candy in the 1970 world premiere of Carlisle Floyd's "Of Mice and Men," Wotan in Richard Wagner's "Walküre" in 1973, Gunther in nine productions of Wagner's "Götterdämmerung" from 1975 to 1983 and three roles in Prokofiev's "War and Peace" in 1990. Last season, Drake took the stage in Mozart's "Marriage of Figaro" and danced the fandango for the first time at the age of 80. Drake, who was legendary for never missing a performance or a rehearsal, did appear tired during his final production. On several occasions, he expressed concern about whether he would "make it through" the production. On Friday, the next-to-last night of the run, Drake sat backstage and told fellow singer Byron Ellis that "all I need is 30 more hours." That he indeed made it through "Macbeth's" entire run would have been gratifying to him. As Ellis, a Seattle Opera compatriot for 26 years, remarked, "Archie would have been devastated if he had not finished his role in the show and someone else would have had to replace him. He was a good trouper, a wonderful comrade." Drake is survived by one niece and four nephews in Britain. A complete listing of Drake's roles at Seattle Opera is posted in the news section on the opera's Web site, www.seattleopera.org. |

This interview was recorded at the Seattle Opera House on August

1, 1987. The transcription was made early in 1990 and published in

Wagner News in April of that year.

It was slightly re-edited and posted on this website in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award-winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.