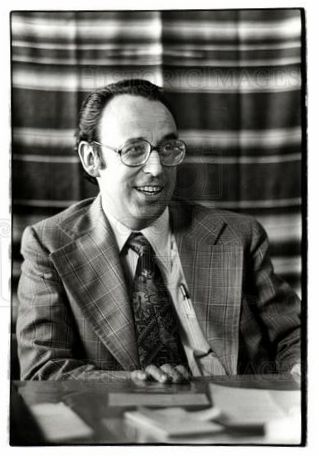

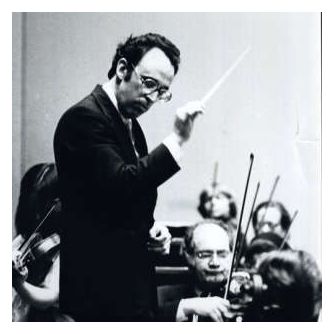

| Henry Holt (April 11, 1934 in Austria

- October 4, 1997 in Charlottesville) was an American conductor, opera

director and music educator.

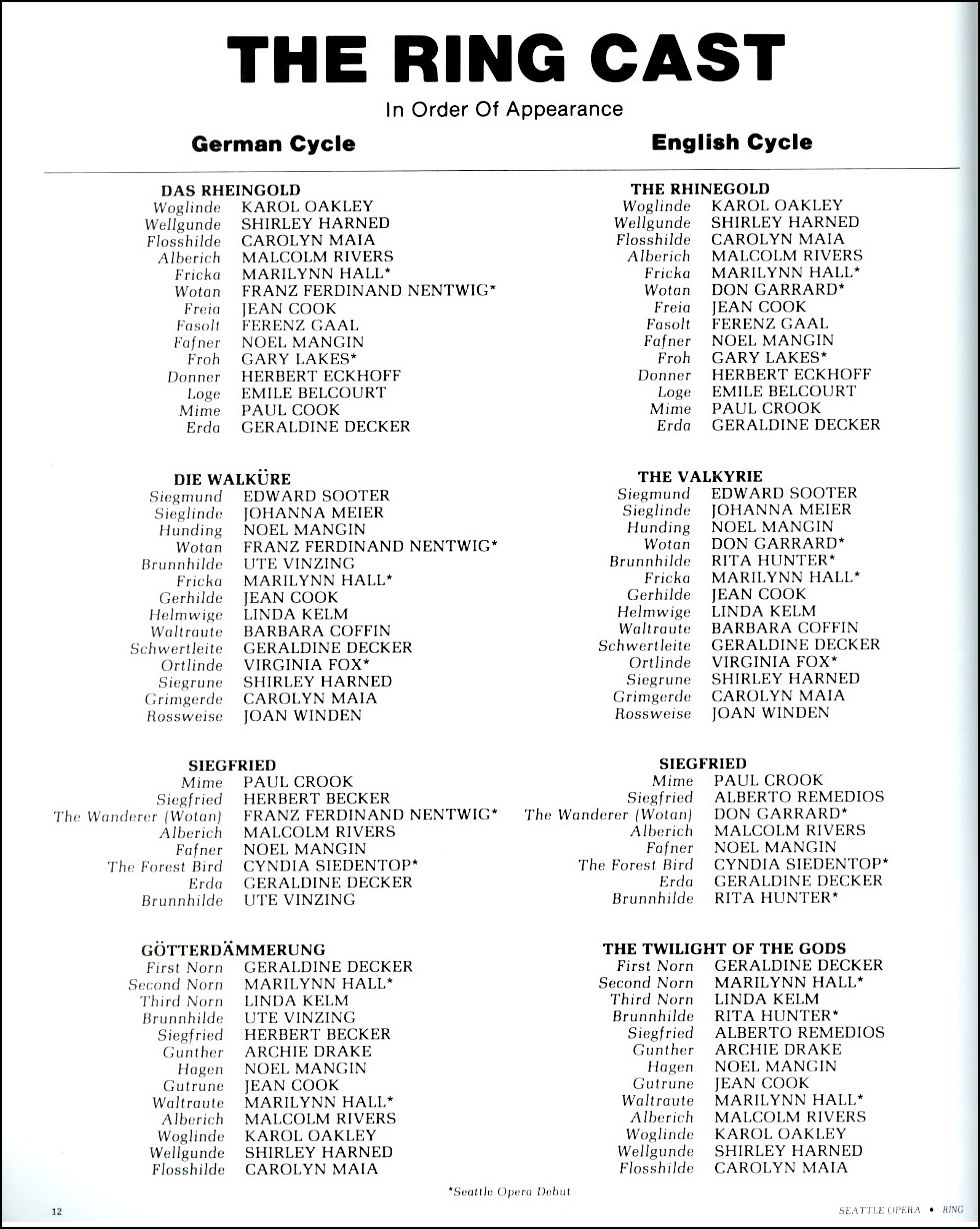

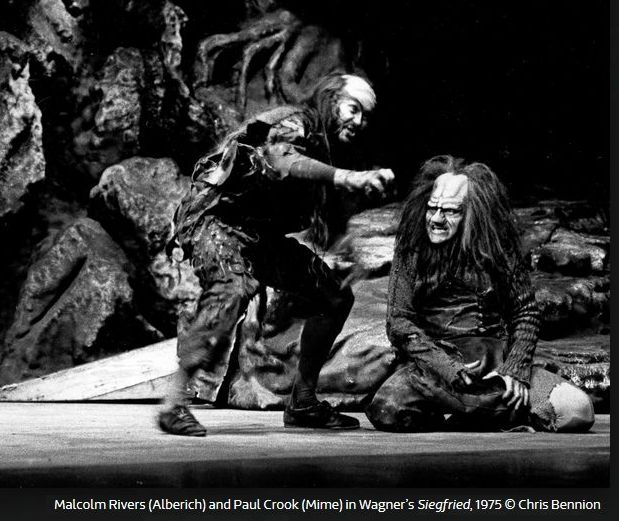

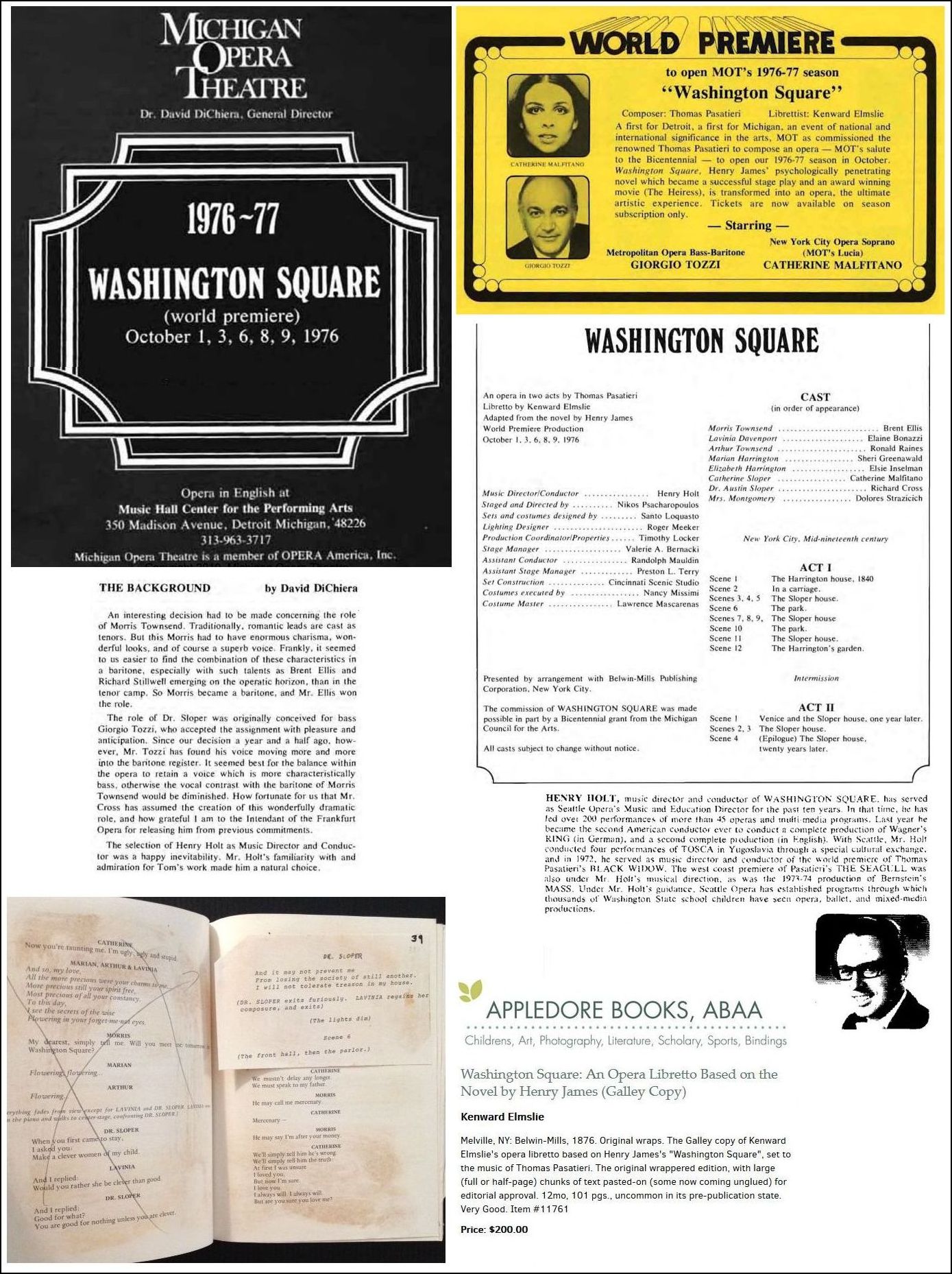

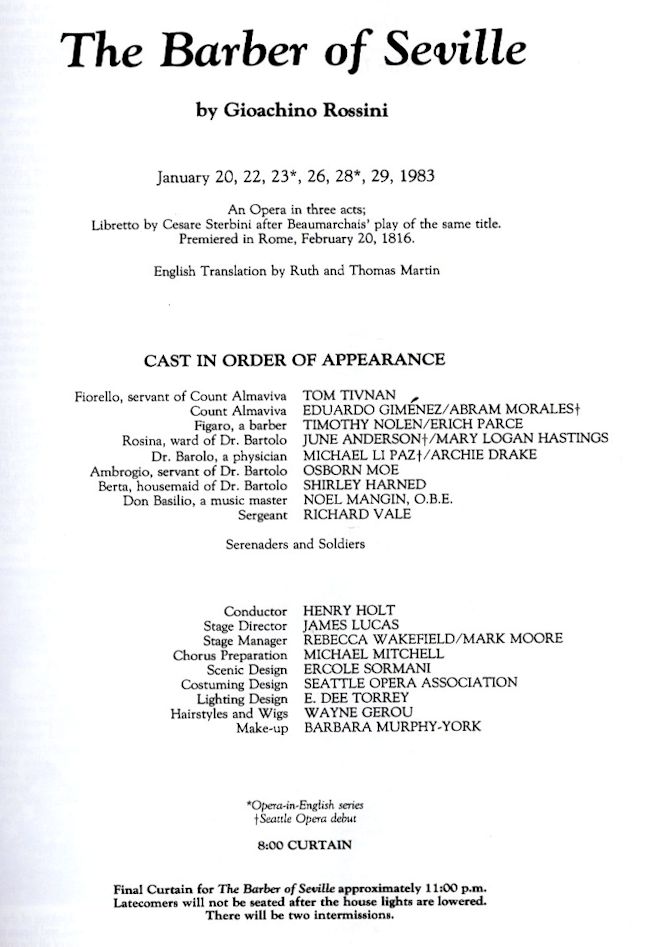

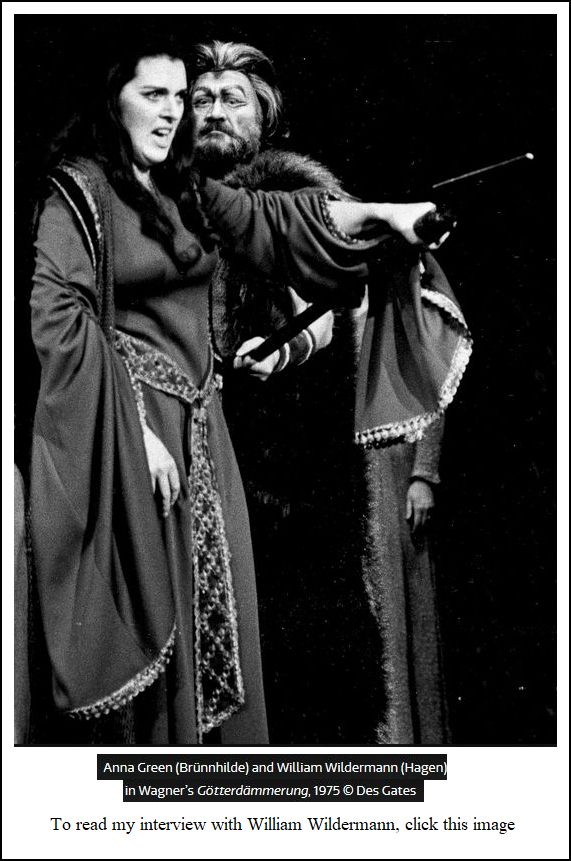

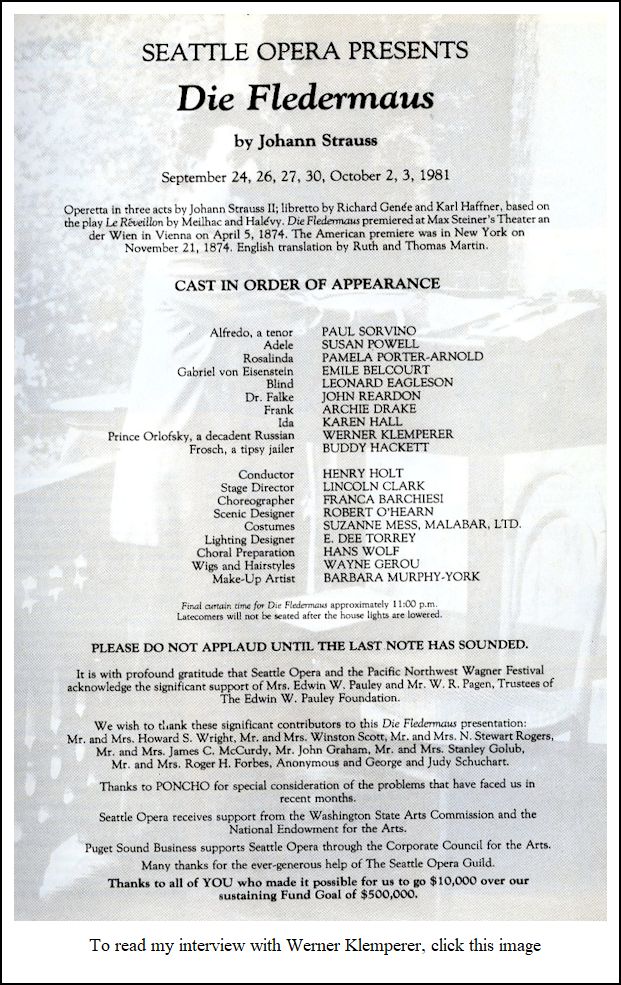

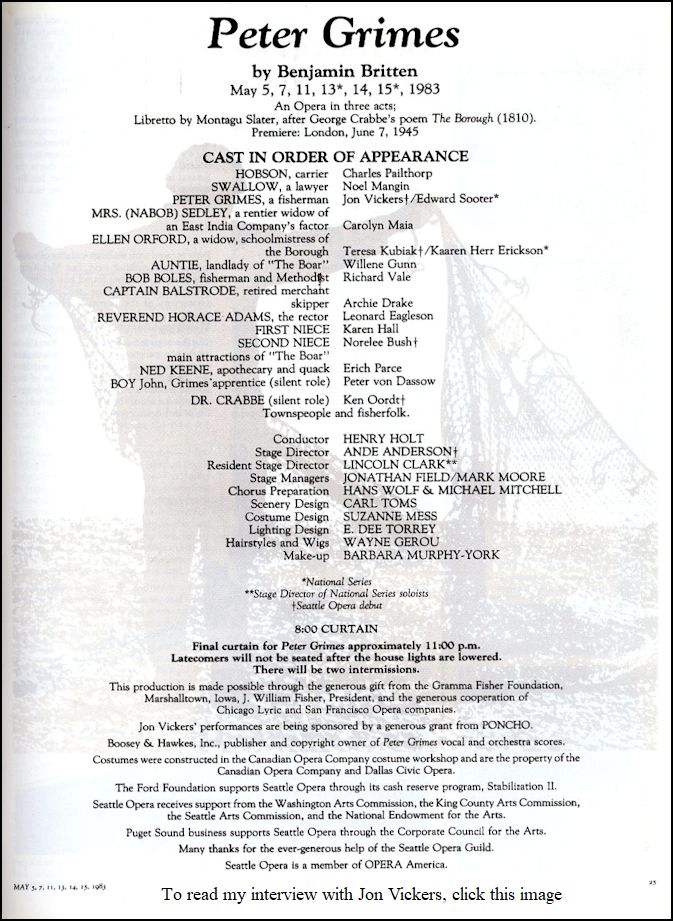

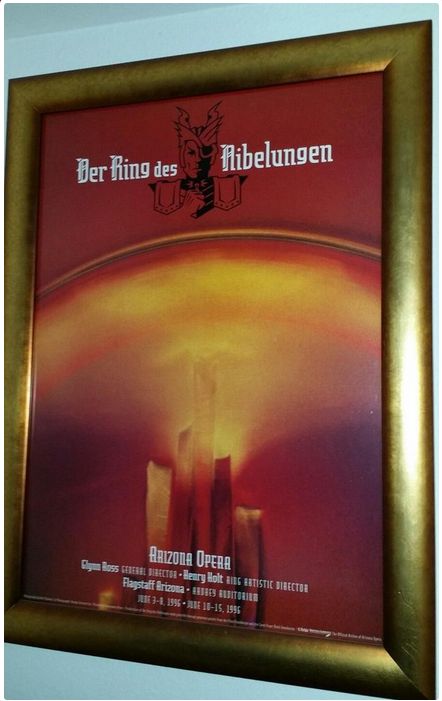

Holt's family fled to the United States from Austria before the Nazi occupation, and Holt grew up in Los Angeles. He was general director of the Portland Opera from 1964-1966, and from 1966 to 1984 he was music director of the Seattle Opera. He co-founded the Pacific Northwest Ballet, and the Pacific Northwest Festival in Seattle. There he performed Richard Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen for ten consecutive years. In 1984, he returned to Los Angeles and became musical, later general director of the Los Angeles Opera Theater, as well as artistic director of the Baton Rouge Opera. As guest conductor he joined the New York City Opera and the Chicago

Opera Theater. Among other things, he conducted the world premiere

of Carlisle Floyd's

opera Of Mice and Men. In 1996 he directed the Ring

at the Arizona Opera. As a music educator he devoted himself especially

to music education for children. He worked with the National Guild

of Community Schools of the Arts, the Kennedy Center Education Program,

and the E.D. Hirsch National Core Knowledge Movement. He also gave

opera workshops at the University of Southern California, Lewis and Clark

College, and Louisiana State University. -- Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Henry Holt: It’s developed

primarily from doing it so many times and with so many different

artists, and having done some of the operas separately in other companies,

but primarily from reworking it every year. I find myself starting

from scratch several months before rehearsals, and trying to rethink

every bar of music, or at least every phrase. I take out some

clean scores, sit down at the piano and start to play, and I try to be

open to discovering new things about the Ring.

Henry Holt: It’s developed

primarily from doing it so many times and with so many different

artists, and having done some of the operas separately in other companies,

but primarily from reworking it every year. I find myself starting

from scratch several months before rehearsals, and trying to rethink

every bar of music, or at least every phrase. I take out some

clean scores, sit down at the piano and start to play, and I try to be

open to discovering new things about the Ring.

BD: So you feed off the audience?

BD: So you feed off the audience? HH: What is most exciting

is to prepare new works, and the only thing I would ever, ever trade

the Ring for would be the opportunity to do a lot of new music.

HH: What is most exciting

is to prepare new works, and the only thing I would ever, ever trade

the Ring for would be the opportunity to do a lot of new music. BD: The rest of the roles can

be performed by the same singers?

BD: The rest of the roles can

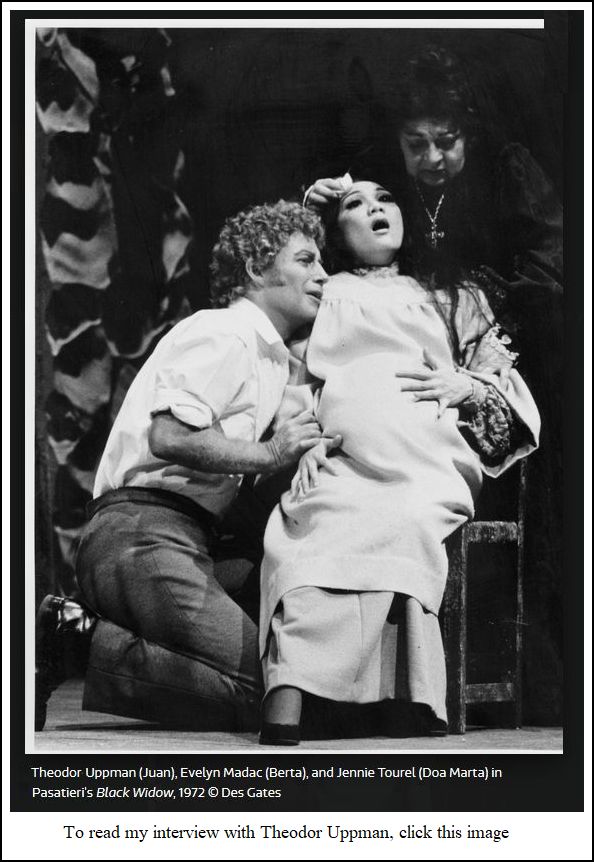

be performed by the same singers? HH: It depends on who they are.

If it’s a singer that I really like a great deal and that I admire

as an artist, then I will try to convince them of the viability of American

opera, and particularly someone like Pasatieri who writes a great

vocal line. I’ll play some music for them. I’ll play some

tapes for them, or I’ll sit down at the piano with them, and go through

something that I particularly like, and say why I think it would be

good for them. I’ve convinced lots of singers to use Pasatieri’s

arias as audition pieces, because some of them are stunning audition

pieces. On the other hand, if it’s a singer that I don’t particular

care for, or that I don’t think would fit into a contemporary American

opera, then I don’t try to convince them of anything. I may be

grateful that they’re going to stick to the standard repertory because

they may not be an asset to our American opera.

HH: It depends on who they are.

If it’s a singer that I really like a great deal and that I admire

as an artist, then I will try to convince them of the viability of American

opera, and particularly someone like Pasatieri who writes a great

vocal line. I’ll play some music for them. I’ll play some

tapes for them, or I’ll sit down at the piano with them, and go through

something that I particularly like, and say why I think it would be

good for them. I’ve convinced lots of singers to use Pasatieri’s

arias as audition pieces, because some of them are stunning audition

pieces. On the other hand, if it’s a singer that I don’t particular

care for, or that I don’t think would fit into a contemporary American

opera, then I don’t try to convince them of anything. I may be

grateful that they’re going to stick to the standard repertory because

they may not be an asset to our American opera. BD: It worked very well. It was an enjoyable

thing to watch, and it was a small-scale work that ran only an hour.

BD: It worked very well. It was an enjoyable

thing to watch, and it was a small-scale work that ran only an hour.

Alice Ehlers (1887-1981) began piano lessons as a child, later studying the instrument under Robert and Leschetizky, and music theory with Schoenberg. In 1909 she matriculated at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik as a piano student. Immediately upon Landowska's appointment as professor of harpsichord in 1913, Ehlers became her pupil and remained with her until 1918. After a successful concert debut in Berlin, she toured as a harpsichordist in Europe, the USSR and the Middle East. She also taught at the Berlin Hochschule until 1933, after which she left Germany, taking up temporary residence in England and Austria. She first toured the USA in 1936, and moved permanently two years later, settling in California and becoming an American citizen in 1943. In addition to making film and radio appearances, Ehlers toured extensively, especially on the Pacific coast. She also had a long association with Dr. Albert Schweitzer both as a student as a colleague. A selection of letters they exchanged between the years of 1928 and 1965 was published in the book Albert Schweitzer & Alice Ehlers - A Friendship in Letters. She was a featured performer in Samuel Goldwyn's Wuthering Heights (1939, shown below), where she performed onscreen Mozart's Rondo Alla Turca for the assembled party guests on a double-manual harpsichord. She remained active as a teacher, first privately, and later as professor of harpsichord at the University of Southern California at Los Angeles, a chair which she held from 1942 until her retirement in 1962.

Paul Hindemith, Alice Ehlers, Rudolf Hindemith (l-r) |

HH: They weren’t as limited as you might think.

Look at how Lully’s operas were produced, and the size of the forces

there, or the late works of Rameau, and others of the French baroque.

But I’m afraid that we don’t have the artists with the right kind

of training. The type of vocalism of that period, and the type

of training that singers went through is very different from what passes

as vocal training today. I’m not saying it was all great, but

it was totally different, and at some point it would be nice to create

a school of baroque performance, and do these works properly. I

don’t think it’s possible to do them properly today. [Yet again,

we can see the amount of progress made since this interview took place!

For instance, let me cite the work of Nicholas Harnoncourt, William Christie and

Nicholas McGegan...]

HH: They weren’t as limited as you might think.

Look at how Lully’s operas were produced, and the size of the forces

there, or the late works of Rameau, and others of the French baroque.

But I’m afraid that we don’t have the artists with the right kind

of training. The type of vocalism of that period, and the type

of training that singers went through is very different from what passes

as vocal training today. I’m not saying it was all great, but

it was totally different, and at some point it would be nice to create

a school of baroque performance, and do these works properly. I

don’t think it’s possible to do them properly today. [Yet again,

we can see the amount of progress made since this interview took place!

For instance, let me cite the work of Nicholas Harnoncourt, William Christie and

Nicholas McGegan...]

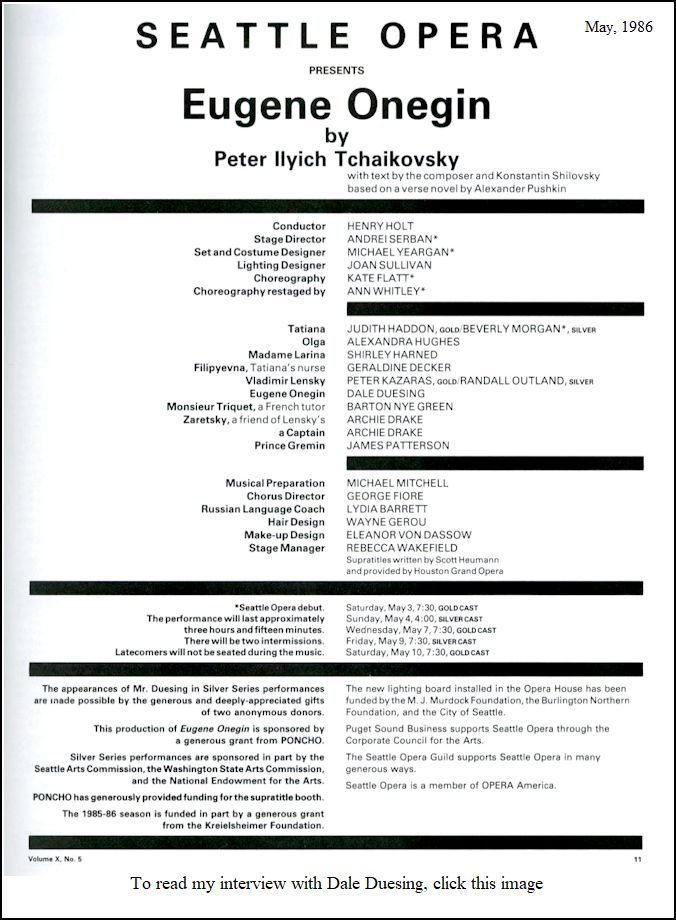

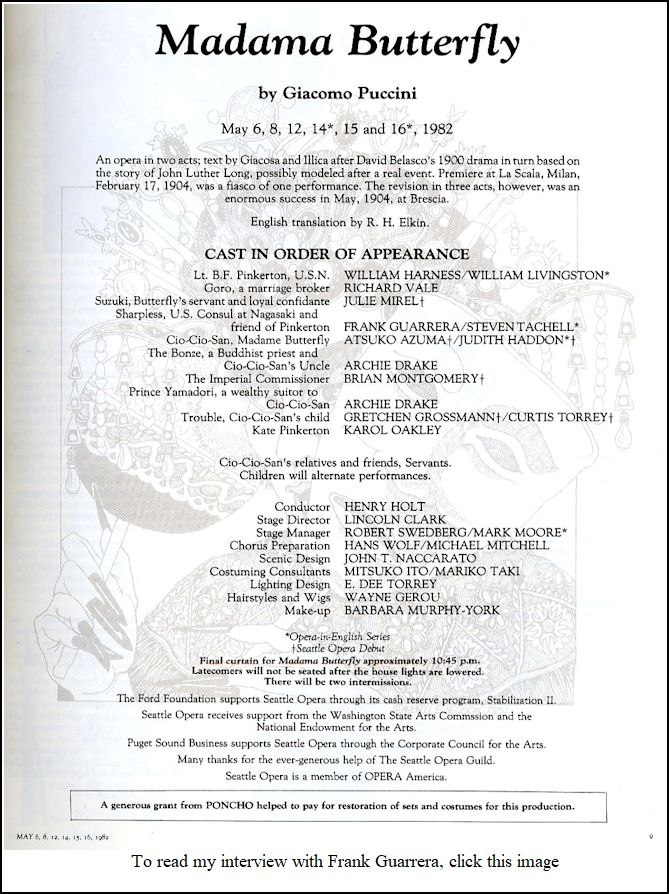

HH: Very much so. I try whenever

possible to get hold of the original source material to see what the

original form of an opera was. For instance, for years I conducted

Madama Butterfly mindless of what the work had been in its original

form, until finally I was able to get all that material together.

Now, some of the rather awkward musical transitions make sense to me

because that’s where the cuts were, and he never really bothered to totally

clean it up. I worked very closely with Carlisle Floyd on revisions

for Of Mice and Men before the first production. An entire

scene was omitted from that opera, but there were two very important

arias in that scene that had to be inserted somewhere else, and we found

the places for them. But we had to do it in a hurry, and it was

done without all the necessary plastic surgery.

HH: Very much so. I try whenever

possible to get hold of the original source material to see what the

original form of an opera was. For instance, for years I conducted

Madama Butterfly mindless of what the work had been in its original

form, until finally I was able to get all that material together.

Now, some of the rather awkward musical transitions make sense to me

because that’s where the cuts were, and he never really bothered to totally

clean it up. I worked very closely with Carlisle Floyd on revisions

for Of Mice and Men before the first production. An entire

scene was omitted from that opera, but there were two very important

arias in that scene that had to be inserted somewhere else, and we found

the places for them. But we had to do it in a hurry, and it was

done without all the necessary plastic surgery.[At this point we went over a few of the specific details of dates and singers for the upcoming Ring to use as promotion on the radio, as well as how people could write to get tickets... which led to a couple of funny stories...]

HH: We’ve got it. We have

three wonderful singers for this, and I’m very pleased with them.

To learn these roles is excruciating. The vocal lines are every

bit as complicated rhythmically, or even more so, than the instrumental

lines. There are things like having to sing seven notes in the

time of five, and always against the beat of the conductor.

HH: We’ve got it. We have

three wonderful singers for this, and I’m very pleased with them.

To learn these roles is excruciating. The vocal lines are every

bit as complicated rhythmically, or even more so, than the instrumental

lines. There are things like having to sing seven notes in the

time of five, and always against the beat of the conductor. BD: Is that what makes it special

— that it is unique?

BD: Is that what makes it special

— that it is unique? BD: You don’t feel that the trade-off

is of more benefit than not having them?

BD: You don’t feel that the trade-off

is of more benefit than not having them? BD: Only three hundred years late...

BD: Only three hundred years late...

[At this point we were abruptly informed that our particular backstage space was needed for something else, so we had to quickly end our conversation.]

© 1980 & 1990 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in on March 19, 1980, and in mid-March of 1990. Portions of the first one were broadcast on WNIB two months after it was recorded, and the second one a few days after it was recorded. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.