A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

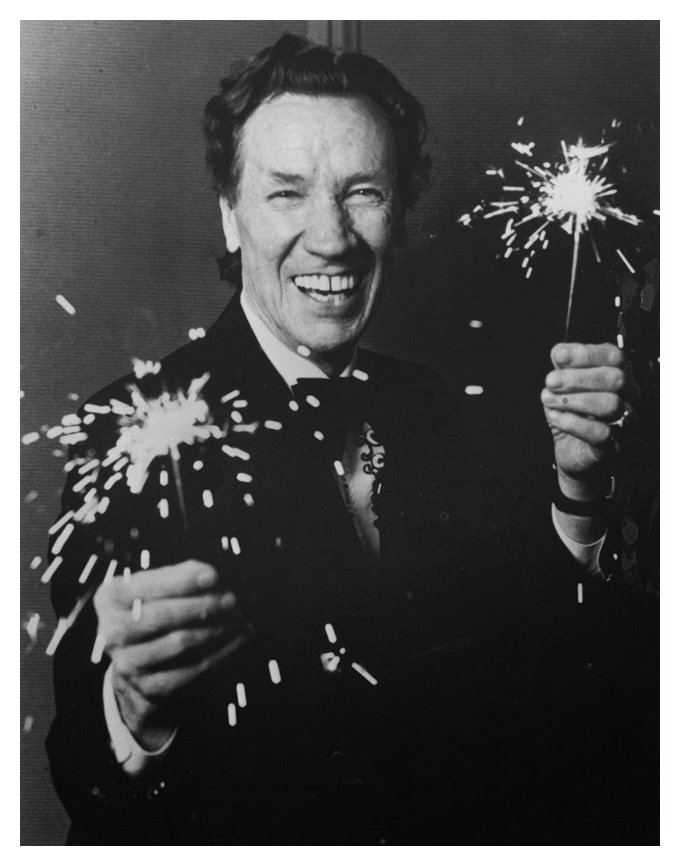

Glynn Ross, 1914-2005: His energy and ideas

built Seattle Opera

By R.M. CAMPBELL, SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER MUSIC CRITIC Published 10:00 pm, Thursday, July 21, 2005 [Text only - photos and links to Bruce Duffie's interviews added for this website presentation.] Glynn Ross was "a giant in American opera," says Seattle Opera General Director Speight Jenkins. Glynn Ross, the "hip huckster of grand opera" who used bumper stickers and slogans, famous singers and Wagner's "Ring" to launch Seattle Opera and make it one of the nation's biggest regional companies, died yesterday in Tucson, Ariz., of complications from a stroke. He was 90. As the company's founding general director, the energetic and creative Ross built Seattle Opera into a vital part of the city's cultural life, nurtured Pacific Northwest Ballet in its early years as part of the opera and made presentation of Wagner's four-opera cycle into a local tradition at a time when mounting it outside Germany was a rarity. Ross also was the organizing force in launching Opera America, a national organization of opera companies, which now numbers more than 100 members. "Glynn Ross was a giant in American opera," said Speight Jenkins, who succeeded Ross as general director. "Seattle Opera exists because of his imagination and ability to sell this art form to the people of Seattle. Our emphasis on Wagner, particularly the 'Ring,' began with Glynn's love for these works and his realization that our public would respond. All American opera lovers owe Glynn a debt, not only for what he did in Seattle but establishing opera in Arizona and having the foresight to dream up Opera America, which now has a vast influence in the world of opera. His abilities as a spokesman and salesman for opera cannot be exaggerated." Arriving in Seattle from Naples, Italy, in 1963, with his Italian wife, their four children, and a letter of intent from the barely born opera company, Ross jumped into action. He was wiry, energetic and determined. During his first season, the company produced "Tosca" and "Carmen," both staged by Ross. Quickly he created longer seasons and publicized them in ways some found amusing, others found appalling but no one could ignore. "He was the greatest sloganeer in opera," said Jenkins. There were bumper stickers that declared "Opera Lives." The acronym WITCO, for "What Is This Thing Called Opera?," appeared all over town. There were skywriting slogans and signs on school buses and cement trucks. One of his more outrageous promotions was for Richard Strauss' "Salome" -- "Get Ahead with Salome." For Puccini's "Boheme," the ad campaign centered on the slogan "Six Old-Time Hippies in Paris," and for Gounod's "Romeo et Juliet," "Two Kids in Trouble, Real Trouble, With Their Families." Seattle Magazine referred to Ross as "the hip huckster of grand opera" and others, "the bantam of the opera." Looking back on those days, in a 1978 profile in the New Yorker, Ross said, "I myself thought it was cheapening to use such methods. But I was merchandising opera, and I'd do anything that would shock the public into coming." They did. The first season drew 10,000. By the third, the number had jumped to 50,000. Soon, Seattle Opera was one of the largest regional companies in the United States, with a big subscription base and a balanced budget.  Within a decade of the company's inaugural season in

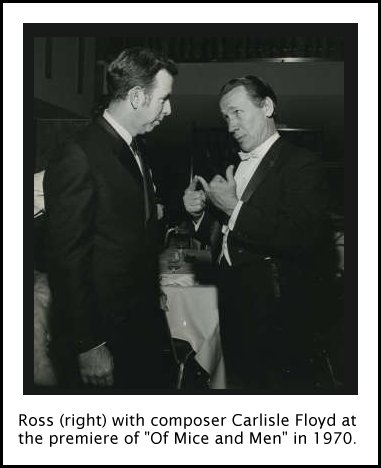

1964, Ross had presented the world premieres of Thomas Pasatieri's

"Black Widow" and Carlisle

Floyd's "Of Mice and Men"; the West Coast premiere of Pasatieri's

"The Seagull," and striking productions of Robert Ward's "The

Crucible" and Stravinsky's "L'Histoire d'un soldat." In 1971, Ross

produced The Who's rock opera "Tommy," starring Bette Midler, at the

Moore Theatre. Four years later, he mounted the company's first

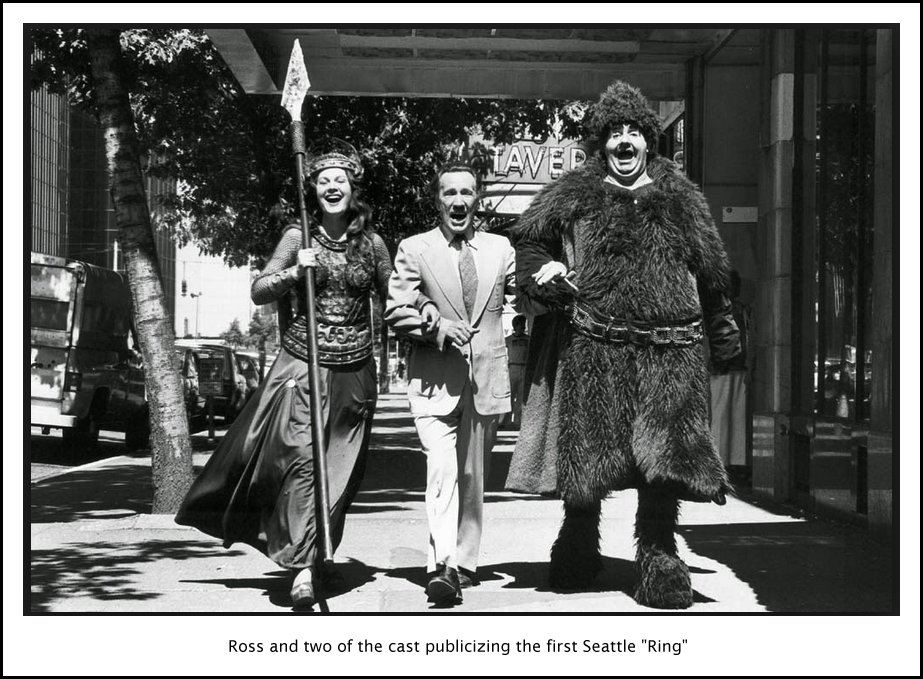

production of Wagner's "Ring," the first American company to produce

the cycle in German and English and within one week. Within a decade of the company's inaugural season in

1964, Ross had presented the world premieres of Thomas Pasatieri's

"Black Widow" and Carlisle

Floyd's "Of Mice and Men"; the West Coast premiere of Pasatieri's

"The Seagull," and striking productions of Robert Ward's "The

Crucible" and Stravinsky's "L'Histoire d'un soldat." In 1971, Ross

produced The Who's rock opera "Tommy," starring Bette Midler, at the

Moore Theatre. Four years later, he mounted the company's first

production of Wagner's "Ring," the first American company to produce

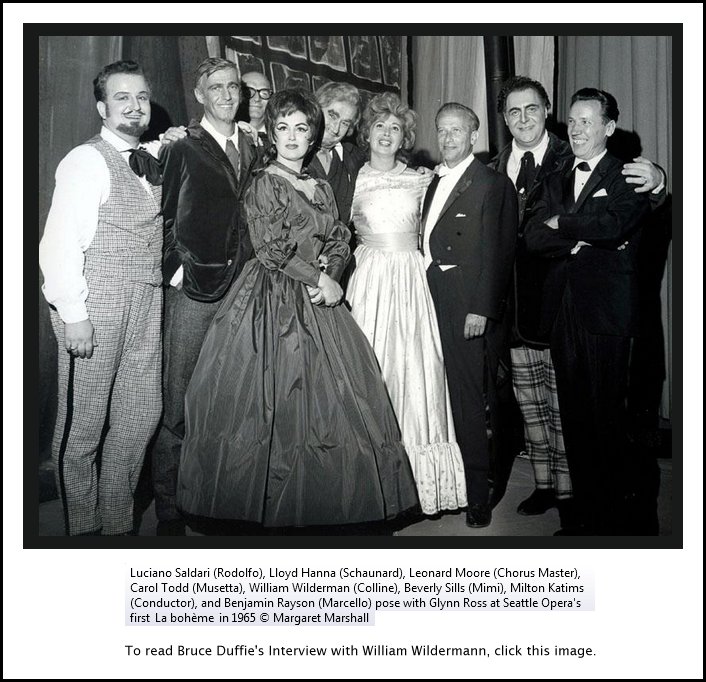

the cycle in German and English and within one week.In his 20-year tenure, Ross presented a number of the most celebrated singers of the day -- sopranos Beverly Sills and Joan Sutherland appeared several times. Other famous singers during his reign included Richard Tucker, Anna Moffo, Birgit Nilsson, Sherrill Milnes, Norman Triegle, Regine Crespin, Dorothy Kirsten, Cornell MacNeil, Roberta Peters, Eileen Farrell, Regina Resnik, Giovanni Martinelli and Grace Bumbry. Ross was a pioneer in presenting opera in English translation. His productions were always in both the original language and, with different principals, in English. Although Seattle Opera, post-Ross, abandoned English-language performances -- with supertitles projected above the stage providing translations instead -- it still maintains two somewhat different casts for most productions. Ross was a conceptualist, a man who could barely contain himself with the ideas he had swarming about his head. He had so many, he kept them in a file in his office. He had the drive of several men and when needed, considerable charm -- enough to obtain financial support from the rich as well as businessmen who might think opera was not for them. He was an expert at convincing the unknowing to try the seemingly arcane pleasures of opera. Certainly, his biggest and most far-reaching idea, beside the company itself, was creating the Pacific Northwest Wagner Festival in the summer of 1975. The production schedule was what Wagner wanted -- the four operas performed within a week -- but at the time was nearly unprecedented outside the Bayreuth Festival, which the composer founded. With limited financial means, the company could not produce a "Ring" on an international scale, but it attracted worldwide attention nonetheless and became the city's best-known cultural product, widely covered by the national and international press. Audiences came from around the world, with Ross proudly counting the number of states and countries represented. The festival ran every summer until 1984. It is now produced approximately every five years. Because Wagner's "Ring" is seemingly ubiquitous in the opera world today, it is hard to realize what a bold move Seattle Opera's production was in the mid-1970s, especially for a young, not-so-large or well-endowed company. At one time, Ross had hoped to make the "Ring" the impetus for an annual summer festival located at a specially constructed facility in Federal Way. The idea was well-received by cultural groups, public officials and patrons until they realized how much it would cost. In some ways, that was the beginning of the end of Ross' regime in Seattle. Many believed he was devoting too much time and resources to the summer venture at the expense of the main season. His critics thought he served up clichés, was too authoritarian and lacked taste: No longer was he the golden boy of Seattle culture. In 1983, the Seattle Opera board forced his retirement, two years before the end of his contract. At the time, he noted: "Success has its penalties. You see, there is one big benefit in failure -- no one envies you. ... We were the 'Mr. Big' in the Seattle arts world." Ross did not stay idle for long. Less than a year later, he was general director of Arizona Opera, a company with financial problems that gave performances in Phoenix and Tucson. Some months after his appointment, a member of the board of trustees said in an interview: "A conversation with Glynn Ross is like a vacation. One comes away with a refreshed sense of renewal and the comfortable feeling that everything is going to be all right. This slight man with blue eyes has ... the energy of Jiminy Cricket, the charm of Cary Grant and the promise of Santa Claus." With many of the same marketing tactics he used in Seattle, Ross built the company and met with success. He even produced the "Ring" not far from the Grand Canyon. He retired in 1998 and returned to Seattle. Ross had a hard-scrabble beginning in South Omaha, Neb. His father was a cowpuncher from Norway, and his mother, the daughter of Swedish farmers, was born in a sod house. In 1937, he went to Boston to study at the Leland Powers School of Radio and Theater, arriving in town with $7 in his pocket. He waited tables, worked in a meat market on Saturdays, wrote publicity material for the Salvation Army and went to Orchestra Hall to hear Serge Koussevitzky conduct the Boston Symphony. His ambition was to be a Shakespearean actor. He staged his first opera, Gounod's "Faust," in Los Angeles three years later, founded the opera department at the New England Conservatory in Boston the following year and, in 1942, joined the U.S. Army. He ended up in Naples, where his Army duties included running a rest camp in an old hotel on the island of Ischia. After the war, the Allies wanted something for the troops to do before they were shipped home, so the great Neapolitan opera house, Teatro di San Carlo, was put to use. Ross made his debut there as a stage director in Mussorgsky's "Boris Godunov" and continued to work at San Carlo for two years. He was the first American to direct in a major Italian house. Ross married Angelamaria Solimene, nicknamed Gio, the daughter of a well-known lawyer, who quietly supervised Seattle Opera's costume shop in its early days. In 1948, Ross and his family returned to the United States, and he began to direct at San Francisco Opera and Los Angeles Opera Theatre, as well as Fort Worth Opera, New Orleans Opera and the Opera Company of Philadelphia. He was a working observer at the Bayreuth Festival in mid-1950s. In 1953, he made his Seattle debut with the Northwest Grand Opera, a forerunner of Seattle Opera, for which he staged several productions. Five years later, he returned to Naples and a job at San Carlo as a stage director. In 1963, Albert Foster, president of newly created Seattle Opera, asked Ross to come to Seattle for an interview, the result of which was an offer to direct the company. In many ways, Ross had one of the most unlikely and successful careers in opera. He broke traditions, created new ones and won supporters and detractors around the globe. He copied no one, for he was always his own man. In addition to his wife, Ross is survived by four children: Stephanie Rogers of San Francisco; Claudia Ross-Kuhn, Seattle; Melanie Ross, who is Seattle Opera's company manager; Tony Ross, Des Moines, Iowa; seven grandchildren and a nephew, Roger Aus, of Omaha, Neb. Services are pending. Donations may be made to Seattle Opera's Wagner Reserve Fund or Arizona Opera. |

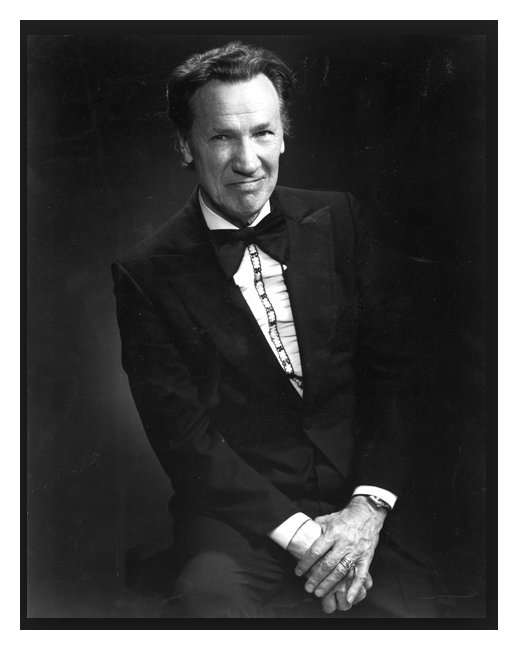

In August of 1987, I was in Seattle for their Ring featuring my old friend Roger Roloff as Wotan. I was also able to interview several of the artists, among them Glynn Ross. As affable as ever, he was pleased to be able to speak with me about some of the aspects of his life . . . . . . . . .

BD

BD