| 'The cultural climate of a country depends

not on what you can purchase, but what you can produce."

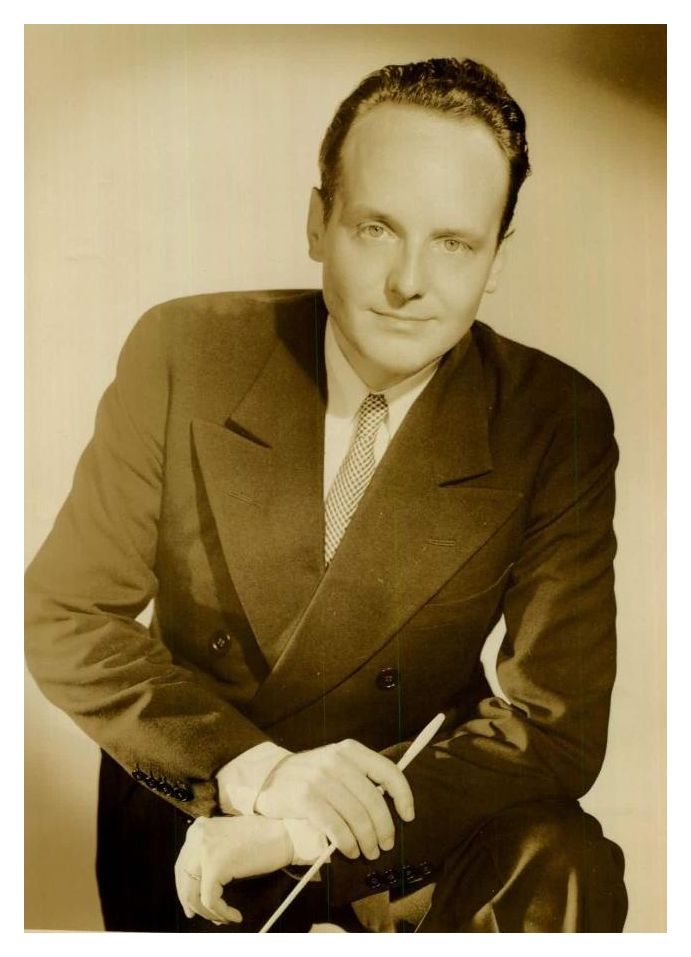

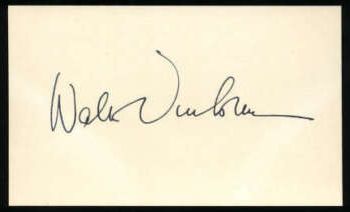

These words of Dr. Walter Ducloux (1913-1997) prophesied

the future of regional opera companies throughout the United

States into the twenty-first century. Centennial Professor

Emeritus of Opera at The University of Texas, Ducloux was an international

conductor, pianist, translator, writer, and educator whose career

spanned over 50 years from Czechoslovakia to California. His

zeal to bring the American public to opera knew no boundaries,

be it in Opera News articles, Longhorn Band football half-time

shows featuring the "Triumphal March" from Aïda, bus

tours to the Dallas Opera's Der Ring des Niebelungen, or

informal chats with colleagues in halls of the School of Music

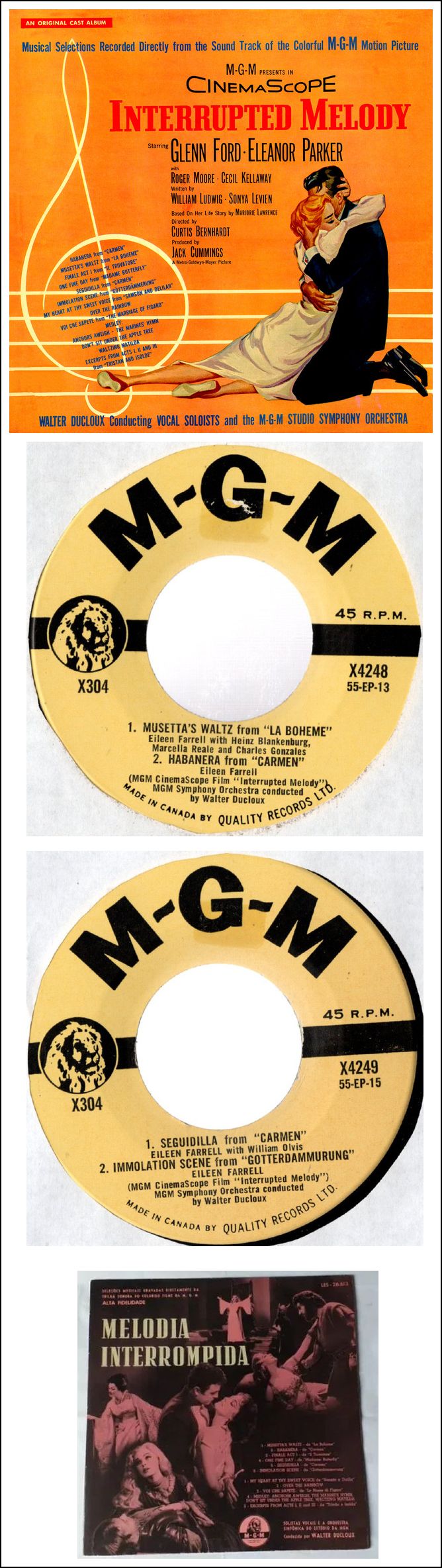

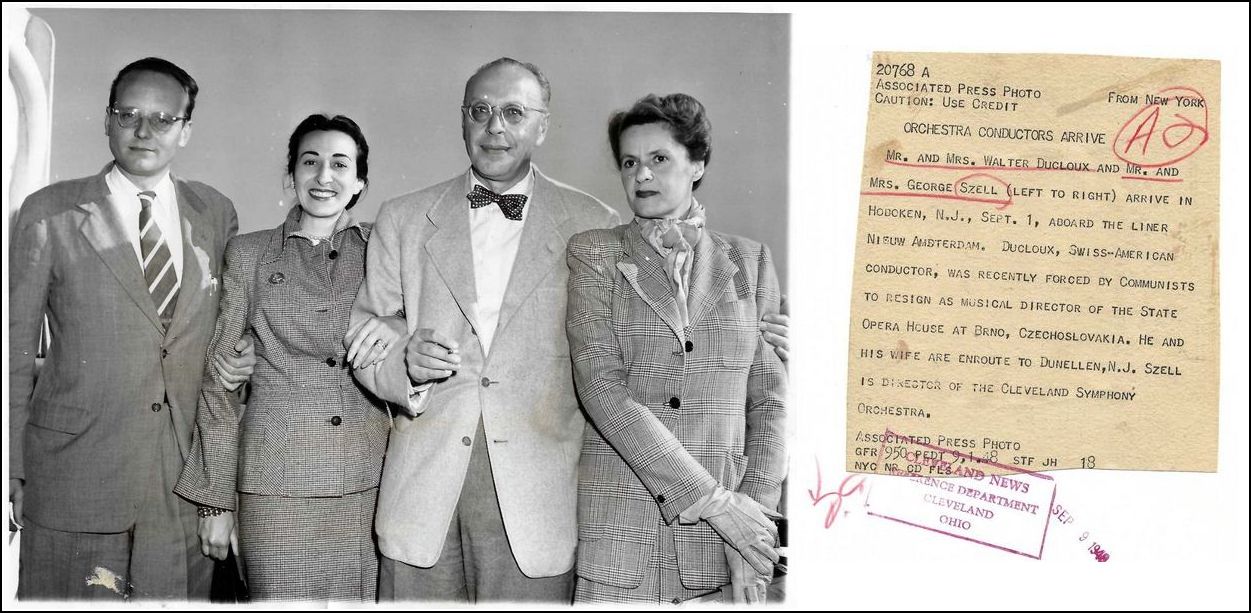

about commedia dell'arte or Strauss' Ariadne auf Naxos. A prodigiously gifted individual, whose expertise included philosophy, drama, and languages, Walter was born in Lucerne, Switzerland, in 1913. After his high school study, which included piano and music theory instruction, he began his university study in Munich where he studied both philosophy and German literature, while simultaneously studying composition and piano. After receiving his doctorate in 1935, he moved to Vienna where he attended conducting master classes with both Felix Weingartner and Josef Krips. After graduating from the Munich Music Academy in 1937, Ducloux returned two years later to his hometown of Lucerne and began his first contract at the Stadttheater and his career as assistant to Bruno Walter at the Lucerne Music Festival, where he first met Arturo Toscanini. Ducloux prepared the chorus of the Verdi Requiem for the Festwochen, and quickly became a close associate to Toscanini because of his fluency in Italian. This encounter with Toscanini became a turning point in his life. Toscanini was beginning his career in America and encouraged Ducloux to follow him to New York in 1939, where Walter became an assistant conductor and opera coach. During the next three years, in addition to his conducting duties and teaching at the University of New Hampshire, Ducloux traveled extensively throughout the U.S. with the renowned Charles Wagner Opera Company. He even conducted The Barber of Seville in Gregory Gymnasium at The University of Texas in 1940. In 1942 the young conductor was drafted into the U.S. Army, where once again his linguistic skills influenced the direction of his life. As a military intelligence officer, he was assigned to General George Patton as aide-de-camp and interpreter in the invasion of Germany. He earned a battlefield commission and Bronze Star for uncovering and thwarting an Axis plot to ambush an American armored battalion. He also worked during and after the war with the Voice of America.  After the war he resumed his conducting career in

Czechoslovakia as guest conductor with the Czech Philharmonic

in Prague, and as the first American conductor of the

Czech National Opera. In 1947 he was named head (General Musikdirektor)

of the Brünn opera, but the communist invasion quickly

ended this phase of his career. In 1948, he assumed the post of

conductor of the Ballet Russe in France where he conducted their

last great tour through Western Europe. In 1949 he returned to America

as guest conductor with both Toscanini's NBC Symphony

and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and began a four-year assignment

with the U.S. State Department as the director of music

services.

After the war he resumed his conducting career in

Czechoslovakia as guest conductor with the Czech Philharmonic

in Prague, and as the first American conductor of the

Czech National Opera. In 1947 he was named head (General Musikdirektor)

of the Brünn opera, but the communist invasion quickly

ended this phase of his career. In 1948, he assumed the post of

conductor of the Ballet Russe in France where he conducted their

last great tour through Western Europe. In 1949 he returned to America

as guest conductor with both Toscanini's NBC Symphony

and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and began a four-year assignment

with the U.S. State Department as the director of music

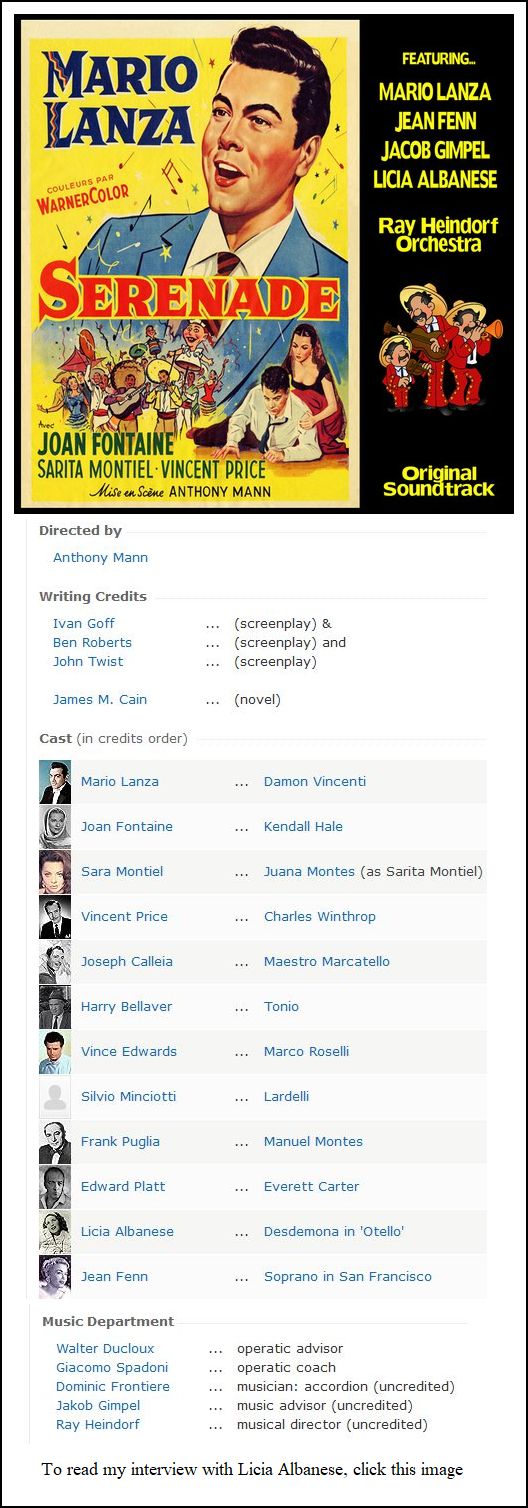

services.In 1953 he moved to Los Angeles following in the footsteps of Carl Ebert at the University of Southern California as professor of opera and director of the USC Opera Theater. This 15-year period showcased over 25 operas including The Rake's Progress (Stravinsky), Liebe der Danae (Strauss), Peter Grimes (Britten), and Mathis der Maler (Hindemith). He also began his "third" career of translating over 25 operas into understandable and singable English. His comprehensive understanding of the slightest nuance and detail of Italian, French, Czech, and German gives his widely-used translations a marvelous depth of understanding. Over a 25-year period, he regularly appeared with the Texaco Metropolitan Opera Quiz (a panel of experts quizzed about opera trivia during the intermission of the Saturday afternoon Metropolitan Opera broadcast). Walter and his wife, opera singer and voice teacher Gina (Rifino), arrived in Austin Texas in the fall of 1968. They brought opera with them. His marvelously witty and comprehensive pre-concert lectures and lecture series induced a love of opera in many who never before had attended an opera. These journeys to the Dallas, Santa Fe, San Francisco, and Houston operas planted the seed for the astoundingly successful Austin Lyric Opera (ALO), which he co-founded in 1986 with Joseph McClain. This "musical congregation" became the core of supporters for the development of the Austin Lyric Opera. He served as ALO's conductor and musical director until 1989. His farewell conducting appearance with the ALO was The Marriage of Figaro in 1994. His statement in 1957, that "opera will never impact American culture until we are producing opera to suit the mainstream environment, using ‘homegrown' American young singers," became the axiom for the unparalleled success of the young, "grassroots" Austin Lyric Opera. In addition to his contribution to the development of the School of Music and to the musical education of University of Texas students, he also envisioned and helped design the Performing Arts Center, which has become one of the foremost cultural centers in Texas. He is survived by Gina, his wife of 53 years, three children, Claude, Phillip, and Denise, and four grandchildren. In addition to the Bronze Star, his numerous awards included five battle stars and a battlefield commission to lieutenant, as well as the Bronze Medal from the government of Italy for his work with Italian Opera in America, and Germany's Verdienstkreuz (Cross of Merit, first class) for accomplishment in German opera. At the University, Walter held an Ashbel Smith chair, the Frank Erwin Centennial chair in Opera, and received the E. W. Doty Award for Excellence. He and his wife also created the Walter and Gina Ducloux Fine Arts Fellowship Endowment at the University. == Biography from the University of Texas

at Austin

|

|

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 15, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990 and 1993. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.