|

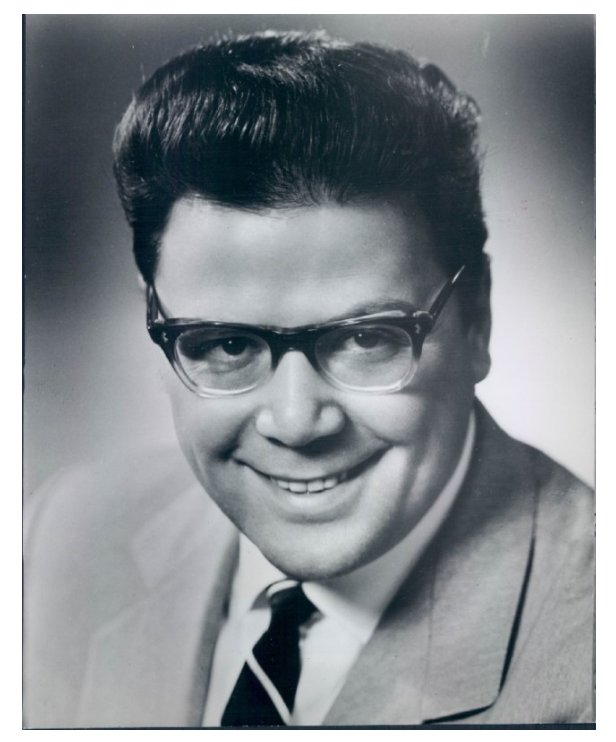

Walter Berry

at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1957 - [American Debut] Marriage of Figaro with Steber, Moffo, Simionato, Gobbi; Solti 1959 - Così Fan Tutte with Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Simoneau, Corena, Stahlman; Krips/Matačič 1960 - Marriage of Figaro with Schwarzkopf, Streich, Ludwig, Waechter; Krips 1961 - Così Fan Tutte with Schwarzkopf, Ludwig, Simoneau, Cesari, Stahlman; Maag Don Giovanni with Waechter, Stich-Randall, Della Casa/Schwarzkopf, Simoneau; Maag Fidelio [Don Fernando] with Nilsson, Vickers, Hotter, Wildermann, Seefried; Maag 1970 - Rosenkavalier [Opening Night] with Ludwig, Minton, Brooks; Dohnányi 1975 - Fidelio [Pizarro] with Jones/Wagemann, Vickers, Crass, Wise; Ahronovich -- [Note: Names which are links refer to my

interviews elsewhere on this site. BD]

|

WB: Yes. Then you have to give much more

voice. If I can give a little example of, we used to sing [sings lightly],

but you have to sing [sings more powerfully]. So coming for the same

point, you have to make it louder. To get the same style you have to

give much more. But there’s one thing. Even in the recitativo, you should never be sloppy

with Mozart. Every note he has written is so important because he was

a genius, and he knows exactly why he has written that longer or shorter.

So even if it is kind of parlando,

it should follow the notes and the rhythm. Mozart has rhythm.

An Italian told me that it is amazing, as an Italian, to see how Mozart has

donned the Italian language when you follow the way he has composed the language

in the music.

WB: Yes. Then you have to give much more

voice. If I can give a little example of, we used to sing [sings lightly],

but you have to sing [sings more powerfully]. So coming for the same

point, you have to make it louder. To get the same style you have to

give much more. But there’s one thing. Even in the recitativo, you should never be sloppy

with Mozart. Every note he has written is so important because he was

a genius, and he knows exactly why he has written that longer or shorter.

So even if it is kind of parlando,

it should follow the notes and the rhythm. Mozart has rhythm.

An Italian told me that it is amazing, as an Italian, to see how Mozart has

donned the Italian language when you follow the way he has composed the language

in the music. BD: But if one of the Rhinemaidens had even been

nice to him a little bit, then the whole story would not have taken place?

BD: But if one of the Rhinemaidens had even been

nice to him a little bit, then the whole story would not have taken place? BD: Is Wozzeck

beautiful?

BD: Is Wozzeck

beautiful? WB: [Even over the phone, one could hear the big

smile on his face] Otto Klemperer was a giant! He was looking

like a giant and was like a monument already. First of all, he was a

very great conductor. I did, as you might know, also Mozart with him.

Without disturbing the style, his Mozart became the dimensions of Beethoven.

For example, in the last scene of Don Giovanni

when the Commendatore appears, it is like Beethoven music because it was

Klemperer. It was himself. He looked and he acted like the giant.

He had this stroke and he had a very strange way to talk, but it didn’t bother

him at all. He was in good health, actually; a very strong man!

And he had an incredible sarcastic sense of humor. There are, you know,

hundreds and thousands anecdotes connected with Otto Klemperer. If

I might mention one which shows what I mean with his sarcastic sense of humor...

When he had an orchestra rehearsal, the bassoon player didn’t have to play

for ten minutes or so. So instead of the music, he had the London Times on his stand. He never thought,

back there where he was sitting, that Otto Klemperer could see him, but he

saw him. He started the rehearsal and he said, “You at the bassoon!

Did you hear what I said?” The man looked up, was shocked at the moment

and said, “Yes, yes, Dr. Klemperer, certainly. I heard it. I heard it.”

And Dr. Klemperer said, “That’s very strange, because I didn’t say anything.”

[Both laugh uproariously] It was typical Otto Klemperer. It just

comes into my mind. I love the story very much. After an all-Beethoven

program, Klemperer was back in his room and a lady came in. She was

so overwhelmed and she had tears in her eyes. She said, “Oh, God, Dr.

Klemperer, it was so beautiful, and I’m so overwhelmed. There is no

other conductor on Earth who can conduct Beethoven like you.” And Klemperer

said, “[matter-of-factly] My dear lady, this is very friendly of you, but

you must consider there is also the great... [pauses] there is... [pauses

again] there’s... [inhales deeply] you’re right!” [Both laugh again]

This was typical Otto Klemperer. We did a recording of Fidelio, and when we had finished the

music, Klemperer left and we made all the dialogues. We said, “We want

the dialogues a little bit, let’s say, contemporary.” Not too spoken

like in the opera house, but more, let’s say, modern. They sent the

tape of it to Klemperer, and wherever we had been, we had to come back to

London to do all the dialogues again.

WB: [Even over the phone, one could hear the big

smile on his face] Otto Klemperer was a giant! He was looking

like a giant and was like a monument already. First of all, he was a

very great conductor. I did, as you might know, also Mozart with him.

Without disturbing the style, his Mozart became the dimensions of Beethoven.

For example, in the last scene of Don Giovanni

when the Commendatore appears, it is like Beethoven music because it was

Klemperer. It was himself. He looked and he acted like the giant.

He had this stroke and he had a very strange way to talk, but it didn’t bother

him at all. He was in good health, actually; a very strong man!

And he had an incredible sarcastic sense of humor. There are, you know,

hundreds and thousands anecdotes connected with Otto Klemperer. If

I might mention one which shows what I mean with his sarcastic sense of humor...

When he had an orchestra rehearsal, the bassoon player didn’t have to play

for ten minutes or so. So instead of the music, he had the London Times on his stand. He never thought,

back there where he was sitting, that Otto Klemperer could see him, but he

saw him. He started the rehearsal and he said, “You at the bassoon!

Did you hear what I said?” The man looked up, was shocked at the moment

and said, “Yes, yes, Dr. Klemperer, certainly. I heard it. I heard it.”

And Dr. Klemperer said, “That’s very strange, because I didn’t say anything.”

[Both laugh uproariously] It was typical Otto Klemperer. It just

comes into my mind. I love the story very much. After an all-Beethoven

program, Klemperer was back in his room and a lady came in. She was

so overwhelmed and she had tears in her eyes. She said, “Oh, God, Dr.

Klemperer, it was so beautiful, and I’m so overwhelmed. There is no

other conductor on Earth who can conduct Beethoven like you.” And Klemperer

said, “[matter-of-factly] My dear lady, this is very friendly of you, but

you must consider there is also the great... [pauses] there is... [pauses

again] there’s... [inhales deeply] you’re right!” [Both laugh again]

This was typical Otto Klemperer. We did a recording of Fidelio, and when we had finished the

music, Klemperer left and we made all the dialogues. We said, “We want

the dialogues a little bit, let’s say, contemporary.” Not too spoken

like in the opera house, but more, let’s say, modern. They sent the

tape of it to Klemperer, and wherever we had been, we had to come back to

London to do all the dialogues again. BD: He has to be a loveable rascal?

BD: He has to be a loveable rascal?

Walter Berry

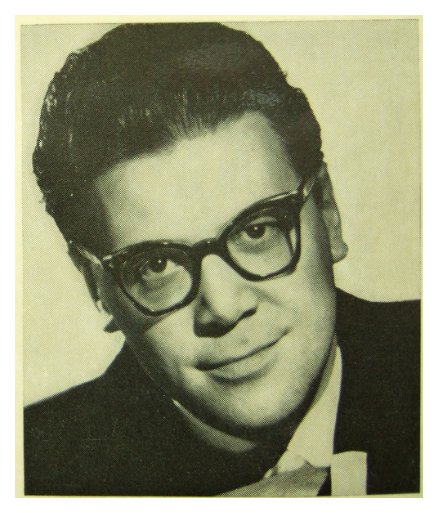

His mellifluous bass-baritone

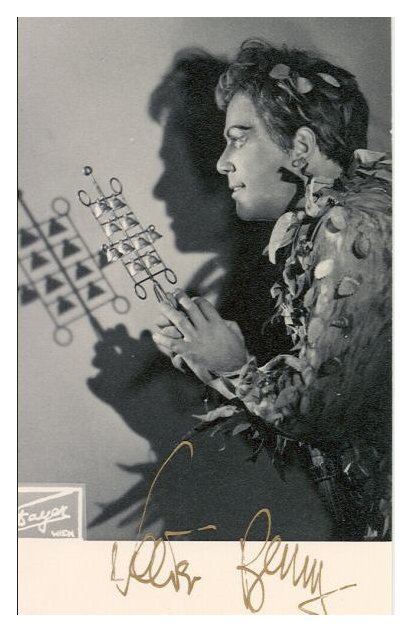

voice delighted opera audiences

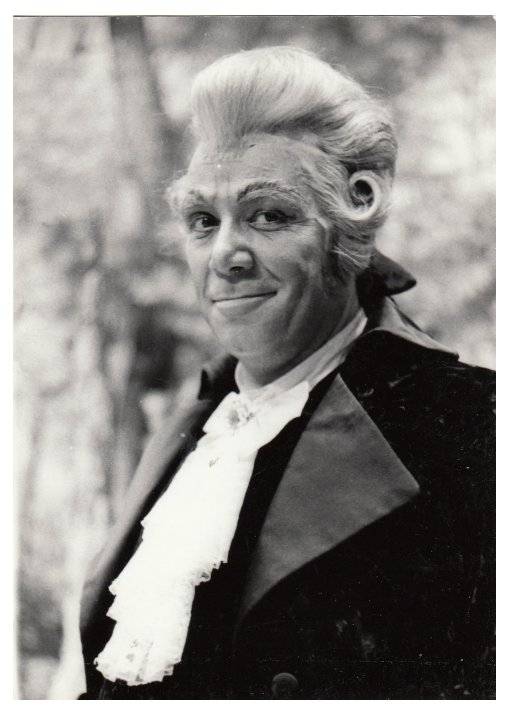

By Alan Blyth, The Guardian, Sunday 29 October 2000 [Text only - photos added for this website presentation] For an appreciable number of years, the role of Papageno at the Vienna State Opera was synonymous with the name of Walter Berry, who has died aged 71. His reading of the role became indelibly imprinted on the mind of audiences, and not only in the Austrian capital; he sang it throughout the German-speaking world and beyond, though, sadly, never in London, where his talents were unaccountably neglected throughout a career of more than 40 years on the operatic stage.

When he was belatedly called to Covent Garden, as late as in 1976, it was as Barak, the plain man personified, in Richard Strauss's Die Frau ohne Schatten, a deeply-felt and moving portrayal in which he deployed his rich and mellifluous bass-baritone voice to notable effect, seconding his vocal attributes with the appropriate body language. In 1986, he returned in a very different Straussian part, that of the impecunious, rascally Count Waldner, in Arabella. The voice of a singer by then well into his 50s seemed hardly affected by the passing years, and, quite recently, he was heard on disc in the tiny, but important, part of the Major Domo to Renée Fleming's Countess Madeleine, in the final scene of Strauss's Cappriccio. Berry brought significance to his phrases, as he had done throughout his lengthy career. That began while he was still a student at the Vienna Music Academy in 1947 (studying with several notable teachers), when he made his stage debut singing Simone in Gianni Schicchi, Falstaff in Nicolai's The Merry Wives Of Windsor, and van Bett in Lortzing's Zar und Zimmermann.

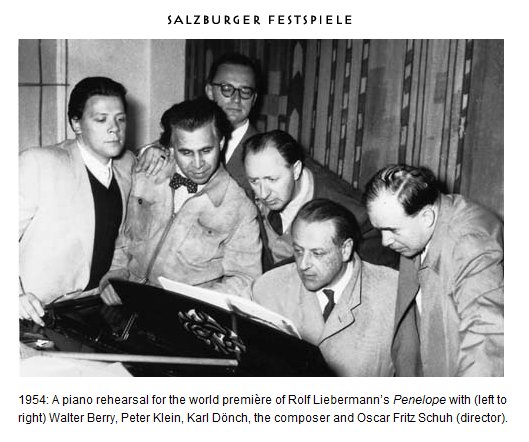

Photos of those productions show the young Berry as obviously a singing-actor of great promise. That was fulfilled when he gained a contract at the Vienna State Opera in 1950, remaining with that ensemble for the rest of his professional life, while commuting in the summer to the Salzburg festival, where he sang regularly from 1952 onwards, creating several roles in operatic premieres.

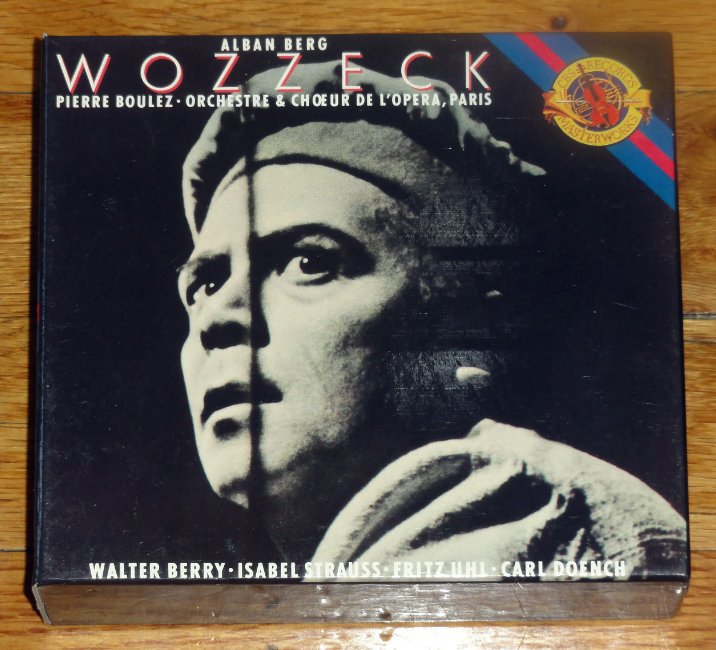

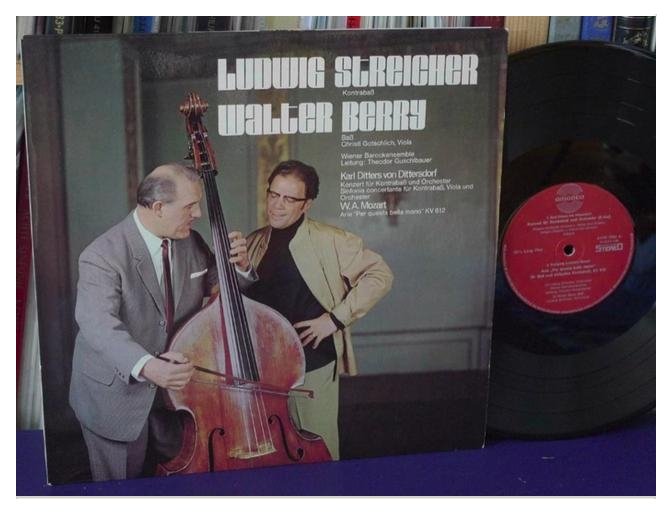

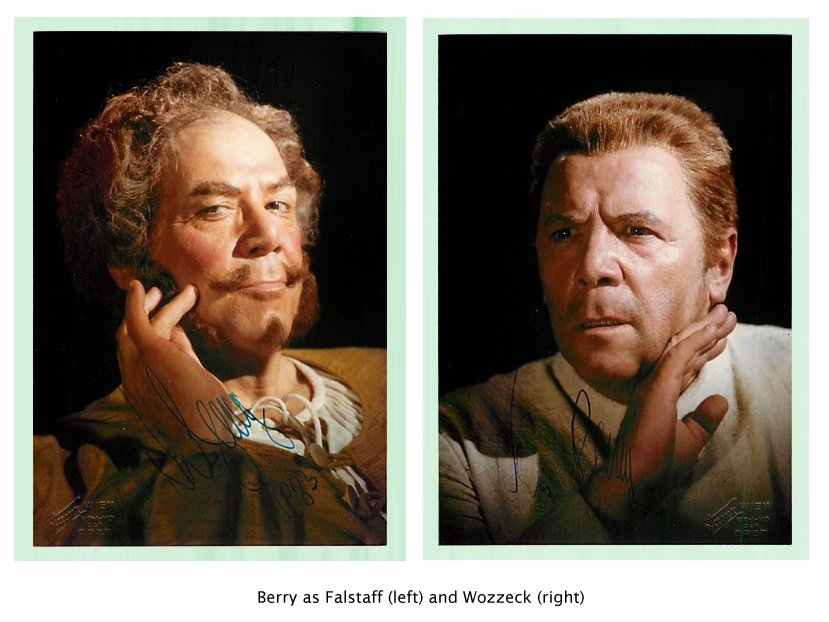

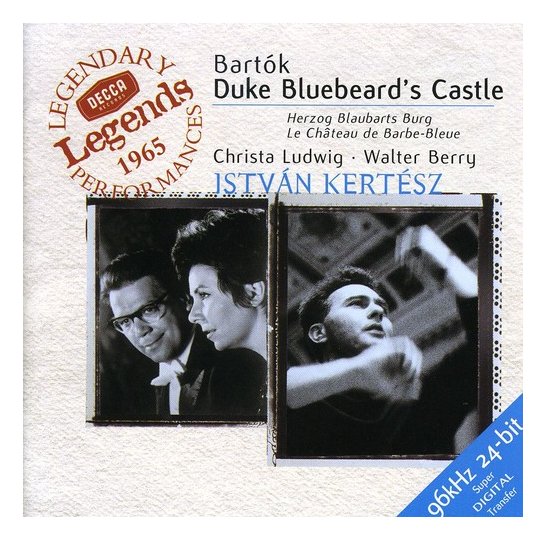

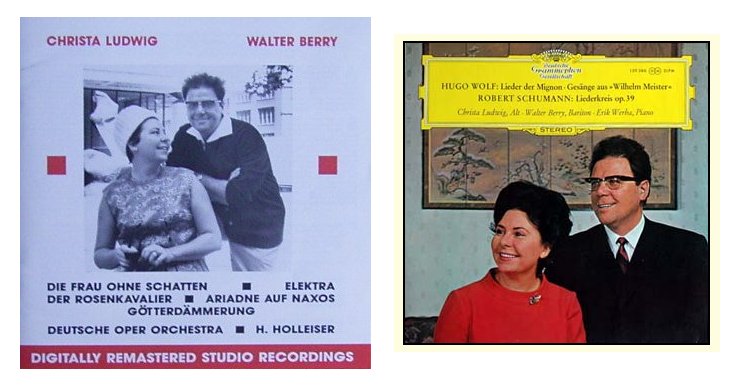

Although he first undertook small roles in Vienna - such as Silvano in Un ballo in maschera - he was soon promoted to Masetto in Don Giovanni, and then to Papegeno and Figaro, which became his calling-card in other houses. He was also a noted Guglielmo, later Don Alfonso, in Così fan tutte, singing the latter role in Karl Bohm's classic 1962 recording for EMI. His first appearances on stage in London took place during the visit of the Vienna State Opera to the Festival Hall in 1954, when he appeared as Figaro and Masetto. As the years went by, Berry's voice grew in strength and range, and he began to tackle more dramatic repertory. His assumption of the title part in Berg's Wozzeck was one of the summits of his achievement, the downtrodden soldier to the life, but he was also admired, among many other parts, as Amonasro (Aïda), Jochanaan (Salome), the four villains in Offenbach's The Tales Of Hoffmann, Cardinal Morone, in Pfitzner's Palestrina, and, eventually, Wotan, in Die Walküre, one of his roles at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, where he made his debut in 1966 as Barak. Another of Berry's specialities was the title role in Bartok's Duke Bluebeard's Castle; his recording of that part, with his then-wife, mezzo Christa Ludwig, and conducted by Istvan Kertész, is still considered one of the best renderings of the opera on disc. This was one of the many examples where Berry subsumed his genial presence in the cause of enacting an unsympathetic part.

Berry and Ludwig married in 1956 and divorced in 1971. While they were a pair, they frequently appeared together on stage and in concert. Berry's truly Viennese Baron Ochs, to Ludwig's authoritative Marschallin, was a partnership worth catching in the 1960s in Vienna. It is preserved on record in the set conducted by Leonard Bernstein, who also accompanied the couple in the piano-version of Mahler's Knaben Wunderhorn cycle.

Berry was an accomplished interpreter of lieder, and a noted soloist in many choral works. He also enjoyed letting down his hair in operetta, especially as Dr Falke, in Die Fledermaus. In everything, his innate musicality was always in evidence. Nothing in his performances was exaggerated; everything emerged from the given text. Nor did he ever extend his talents beyond their natural limits, which probably accounts for the fact that his career lasted so long. He is survived by his son. • Walter Berry, opera singer, born April 8 1929; died October 27 2000 |

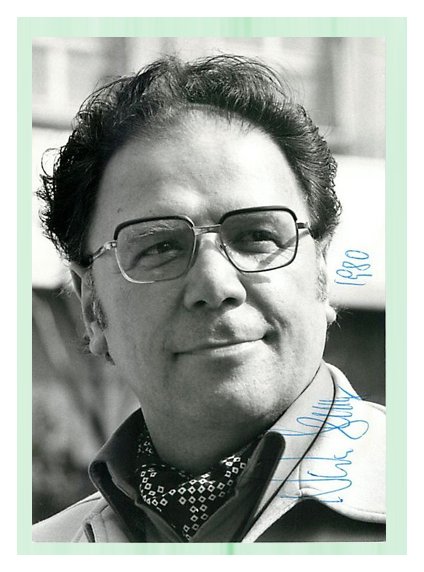

This interview was recorded on the telephone on June 14, 1985.

Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB the following month, and in 1989,

1994, 1998 and 1999. It was transcribed posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.