|

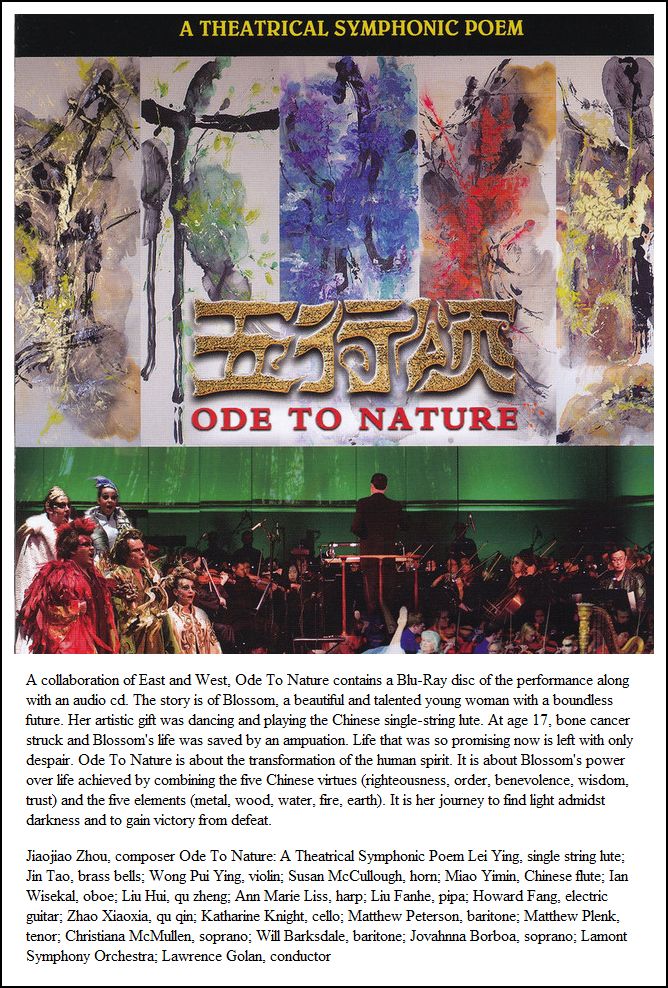

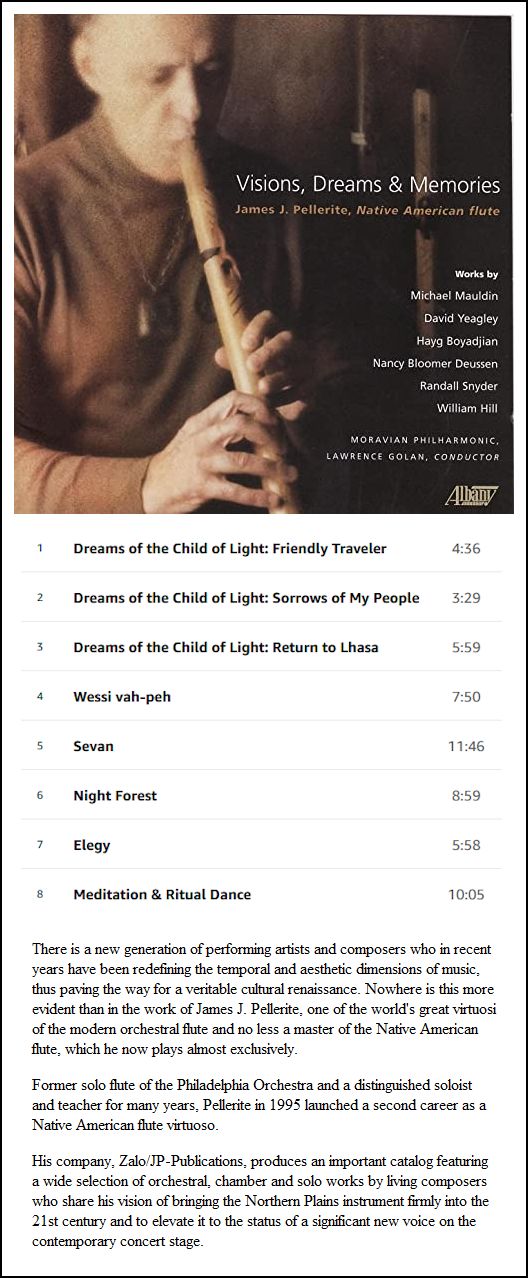

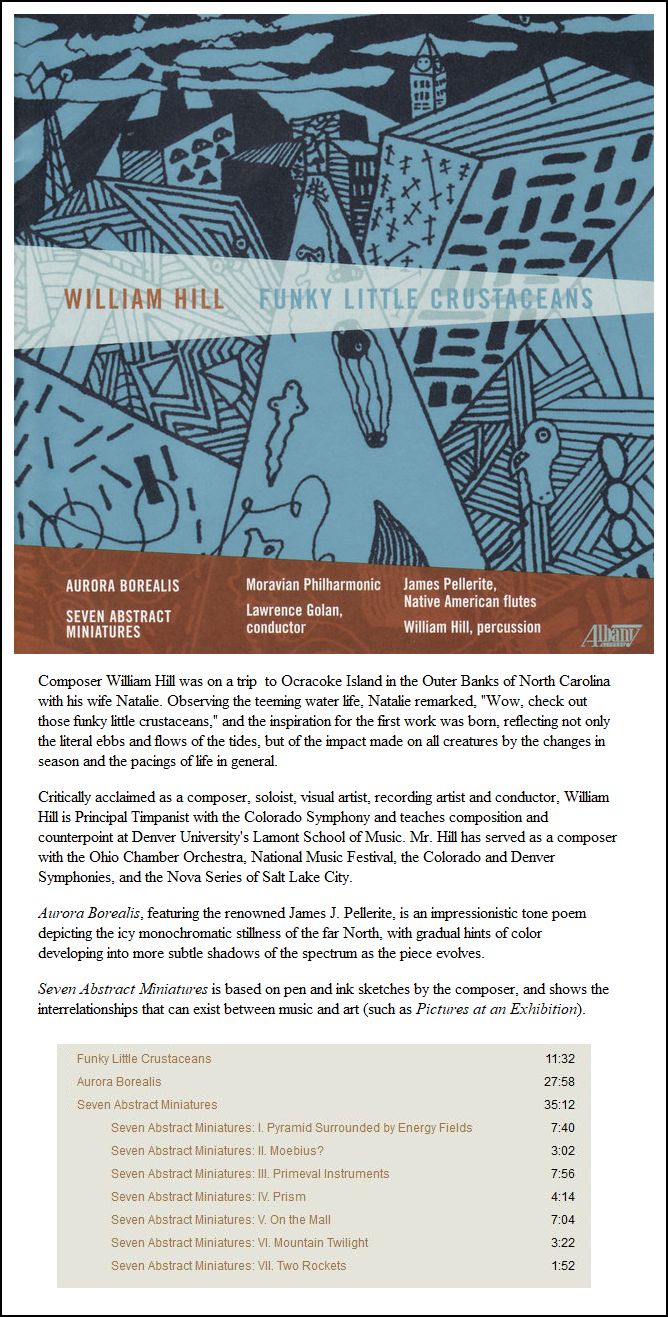

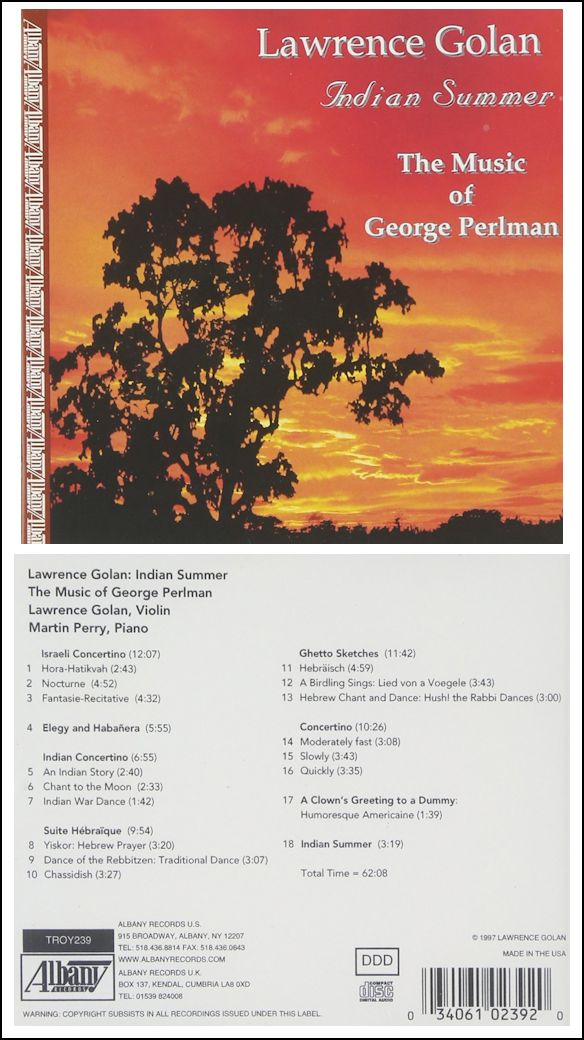

Vibrant, inspired performances, imaginative programming and an evocative command of different styles and composers are the hallmarks of American conductor Lawrence Golan. Newly appointed Principal Guest Conductor of Germany’s Bayerische Philharmonie in April 2021, Golan’s Music Directorship with the Yakima Symphony Orchestra in Washington state has been renewed for seven more years (through the 2028-29 season) and with Pennsylvania’s York Symphony Orchestra for five more years (through the 2024-25 season). A dynamic, charismatic communicator, he also continues as Music Director of Colorado’s Denver Philharmonic, and of the Lamont Symphony Orchestra and Opera Theatre at the University of Denver. Having conducted throughout the United States and in Bulgaria, Canada, China, Czech Republic, El Salvador, England, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan, Maestro Golan continues to develop relationships with orchestras nationally and abroad. Highlights of the upcoming 2021-22 season include the 50th anniversary season of the Yakima Symphony Orchestra, which will feature a gala performance by violinist Joshua Bell, and two recordings, one with the Villalobos Brothers, and one featuring Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 2, “Lobgesang,” with the Yakima Symphony Chorus. Maestro Golan will travel to Granada, Spain to conduct the finals of the María Herrera International Piano Competition and to Munich, Germany for his first concert as Principal Guest Conductor of the Bayerische Philharmonie in July of 2022. Additionally, Maestro Golan has a new book out called Score Study Passes published by Globe Edit and a new composition, Fantasia for Orchestra, distributed by Notation Central. Summer 2021 events include the August 6 release by Centaur Records of "Lawrence Golan, Fantasia" as well as the York Symphony Orchestra’s Open Air Summer Series at the York Fairgrounds. Highlights from recent seasons include return engagements with Italy’s Orchestra Sinfonica Città di Grosseto, the Tucson Symphony Orchestra, the Portland Ballet Company and the Colorado Music Festival, as well as debuts with Italy’s Orchestra Sinfonica di Sanremo, Mexico’s Orquesta de Cámara de Bellas Artes, China’s Wuhan Philharmonic, the Maui Pops Orchestra, the Batumi Music Festival in Georgia, Eastern Europe, and a 14-city tour of China with the Denver Philharmonic. As a recording artist, Mr. Golan has made several recordings, both as conductor and as a violinist. His latest orchestral recording was the 2018 Albany Records release of the world premiere Blu-ray disc and audio CD of composer Jiaojiao Zhou’s theatrical symphonic poem Ode to Nature with the Lamont Symphony Orchestra and producer Dennis Law. Mr. Golan has recorded three CDs with the Moravian Philharmonic for Albany Records. The most recent, “Tchaikovsky 6 & Tchaikovsky 6.1” featuring the composer’s Symphony No. 6 and the recording premiere of Tchaikovsky 6.1 by Peter Boyer (a work commissioned by Golan), won two Prestige Music Awards. “Funky Little Crustaceans” features orchestral music by Colorado composer William Hill, and “Visions, Dreams & Memories” is a collection of works for Native American flute and orchestra with James Pellerite, former Principal Flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Golan’s recording of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 & William Hill’s Beethoven 7.1 garnered two Global Music Awards. As a violinist, Golan recorded "Fantasia; a collection of works for solo violin" and “Indian Summer: The Music of George Perlman,” which won two Global Music Awards. A staunch advocate for music education, Lawrence Golan has been Director of Orchestral Studies and head of the graduate conducting program at the University of Denver since 2001. There he has won eight ASCAP Awards for Adventurous Programming of Contemporary Music, three Downbeat Magazine Awards for “Best College Symphony Orchestra," and The American Prize for Orchestral Performance – Collegiate Division. His latest honor is the 2021 Distinguished Scholar Award from the University of Denver. An accomplished violinist, Golan served as Principal Second Violinist of the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra (1989-1990) and then Concertmaster of the Portland Symphony Orchestra for eleven years (1990-2001), before focusing his career on the podium. He has appeared as soloist with numerous orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, and continues to perform, primarily to benefit orchestras of which he is Music Director. As a composer/arranger, Golan’s edition and reduced orchestration of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker is published by Spurwink River Publishing. It is used by orchestras and ballet companies across North America. His scholarly-performing edition of the solo violin works of J. S. Bach, which includes a handbook on Baroque Performance Practice, and The Lawrence Golan Violin Scale System are both published by Mel Bay Publications. Golan’s Fantasia for Solo Violin is published by LudwigMasters and won the Global Music Award for composition in 2011. A recording of the piece appears on both the Ablaze Records disc "Millennial Masters Vol. 9" and the Centaur Records CD "Lawrence Golan, Fantasia." A native of Chicago, Lawrence Golan comes from a musical family. His father, the late Joseph Golan, was a member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty-nine years and Principal Second Violinist for thirty-five of those years. Lawrence Golan received his Bachelor of Music in Violin Performance and Master of Music in Violin Performance and Orchestral Conducting from the Indiana University School of Music and his D.M.A. in Violin Performance and Orchestral Conducting from the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. In 1999 he was awarded Tanglewood Music Center’s Leonard Bernstein Conducting Fellowship, and in 2002, Aspen Music Festival’s Conducting Fellowship. Mr. Golan’s previous positions include Resident Conductor, Phoenix

Symphony (2006-2010), Music Director, Phoenix Youth Symphony (2006-2009),

Music Director, Colorado Youth Symphony Orchestras (2002-2006), founder

and Artistic Director, Atlantic Chamber Orchestra (1998-2003), Music Director,

Portland Ballet Company (1997-2013), and Music Director, Southern Maine

Symphony Orchestra (1990-2001). Lawrence and his wife Cecilia, who is

from Buenos Aires, Argentina, have two young children. == Biography from the artist’s website

|

|

Considered among the best of the 20th century American makers, Franz Kinberg was born in 1920 in Serbia, and studied with Lajos Kain in Zrenjanin from 1937-39. He then worked for several shops over the next decade, including Franz Schneider in Zagreb, Remenyi in Budapest, and Hofmann & Czerny in Vienna. Kinberg left for the U.S. in 1949, the same year he won the Gold Medal at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Violin Making at The Hague. He was employed by Kagan and Gaines in Chicago until his retirement in 1982. His instruments have been owned by the distinguished concertmasters Mischa Mischako and Sidney Harth as well as members of The Philadelphia Orchestra and the Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh symphonies. Kinberg violins are in demand for their superb craftsmanship, strength, broad and rich tonal palette, ease of playing, and ample power. |

| The Stradivari Society is a philanthropic

organization based in Chicago, Illinois, best known for its arranging deals

between owners of antique string instruments - such as those made by luthiers

Antonio Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri - for use by talented musicians

and performers. The Stradivari Society does not hold title to the instruments.

The Society was founded by Geoffrey Fushi and Mary Galvin in 1985 when Galvin, wife of then-president of Motorola, Bob Galvin, was approached by Fushi and Robert Bein from Bein & Fushi Violins of Chicago, to lend the Ruby Stradivarius of 1708 that he had previously sold to her to a promising violinist, Dylana Jenson. Seeing that such rare violins were very expensive and difficult to obtain, Galvin and Fushi designed the structure and name of the society after lending another violin when Dorothy DeLay of the Juilliard School asked Fushi for a violin for her most promising student, then ten-year-old Midori. Enjoying the experience of lending such beautiful violins to those who could use them to grow and launch their careers, a string of loans followed. Awardees include Joshua Bell, Gil Shaham, Paul Huang, Yi-Jia Susanne Hou, Leila Josefowicz, Philippe Quint, Sarah Chang, Janine Jansen, Vadim Repin, Kristóf Baráti, Hilary Hahn, Maxim Vengerov, and Paul Coletti, all of whom have enhanced their careers playing violins the Society arranged for them to borrow. The Society's two dozen patrons are each given tri-annual concerts by their sponsored musician during its three-year period. Each artist is responsible for insuring the instrument, and its delivery to The Society's curator, John Becker. Inspection and service is performed exclusively by Becker three times yearly, and cannot be done by any other luthier without permission. The instrument is often purchased by the artist from its patron, with The Society acting as liaison. |

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 25, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2000. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.