|

Midori Goto (五嶋 みどり, Gotō Midori, born October 25, 1971) who performs under the mononym Midori, is a Japanese-born American violinist. She made her debut with the New York Philharmonic at age 11 as a surprise guest soloist at the New Year's Eve Gala in 1982. In 1986 her performance at the Tanglewood Music Festival with Leonard Bernstein conducting his own composition made the front-page headlines in The New York Times. Midori became a celebrated child prodigy, and one of the world's preeminent violinists as an adult. Midori has been honored as an educator and for her community engagement endeavors. When she was 21, she established her foundation Midori and Friends to bring music education to young people in underserved communities in New York City and Japan, which has evolved into four distinct organizations with worldwide impact. In 2007, Midori was appointed as a UN Messenger of Peace. In 2018 she joined the violin faculty at the Curtis Institute while remaining on the USC Thornton School Of Music Violin faculty holding the Judge Widney Professor of Music Chair. She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2012.

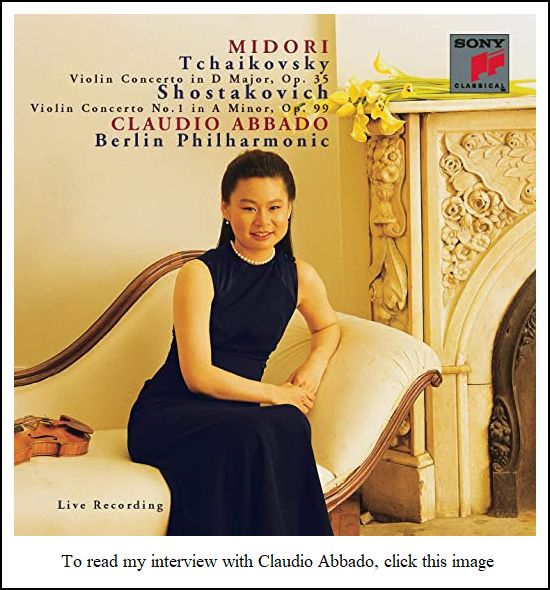

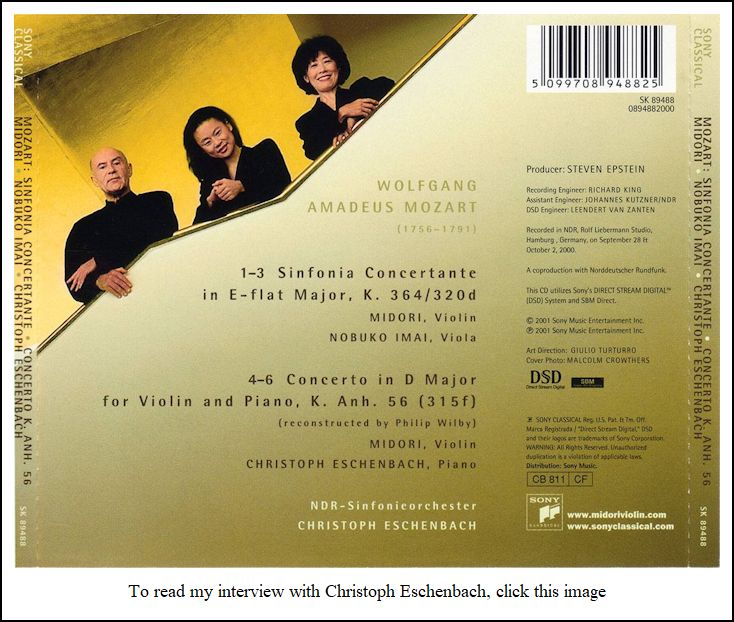

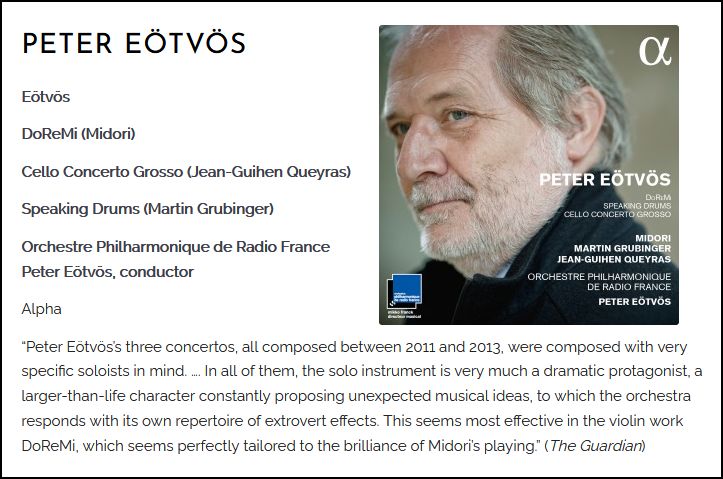

In 1986 came her legendary performance of Leonard Bernstein's Serenade at Tanglewood, conducted by Bernstein [shown together in the photo at right]. During the performance, she broke the E string on her violin, then again on the concertmaster's Stradivarius after she borrowed it. She finished the performance with the associate concertmaster's Guadagnini and received a standing ovation. The next day's The New York Times front page carried the headline, "Girl, 14, Conquers Tanglewood with 3 Violins". When Midori was 15, she left Juilliard Pre-College after four years and became a full-time professional violinist. In October 1989, she celebrated her 18th birthday with her Carnegie Hall orchestral debut, playing Bartok's Violin Concerto No. 2. She made her Carnegie Hall recital debut in 1990 four days before her 19th birthday. Both performances were critically acclaimed. In 1990, she also graduated from the Professional Children's School which she attended for academic subjects. In 1992, she formed Midori and Friends, a non-profit organization that aims to bring music education to children in New York City and in Japan after learning of severe cutbacks to music education in U.S. schools. Her organization Music Sharing began as the Tokyo branch-office of Midori and Friends, and was certified as an independent organization in 2002. Music Sharing focuses on education about Western classical music and traditional Japanese music for young people, including instrument instruction for the disabled. Its International Community Engagement Program is a training program for internationally chosen aspiring musicians that promotes cultural exchange and community engagement. In 2000, Midori graduated magna cum laude from the Gallatin School at New York University with a bachelor's degree in Psychology and Gender Studies, completing the degree in five years while also continuing to perform in concerts. She later earned a master's degree in psychology from NYU in 2005. Her master's thesis was about pain research. In 2001, Midori had returned to the stage and took a teaching position at the Manhattan School of Music. Also in 2001, with the money Midori received from winning the Avery Fisher Prize, she established the Partners in Performance program focusing on classical music organizations in smaller communities. In 2004, Midori launched the Orchestra Residencies program in the U.S. for youth orchestras, which was expanded to include collaborations with orchestras outside the U.S. in 2010. In 2004, Midori was named a professor at University of Southern California's Thornton School of Music where she is holder of the Jascha Heifetz Chair. She became a full-time resident of Los Angeles in 2006 after a period of bicoastal commuting, and was promoted to the chair of the Strings Department in 2007. In 2012 she was named distinguished professor at USC, elected to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and was awarded an honorary doctorate in music by Yale University. Midori was Humanitas Visiting Professor in Classical Music and Music Education at Oxford University 2013–2014. She joined the violin faculty of Philadelphia's Curtis Institute in the 2018–2019 academic year while remaining on the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music's violin faculty as a Judge Widney Professor of Music. In addition to being named Artist of the Year by the Japanese government (1988) and the recipient of the 25th Suntory Music Award (1993), Midori has won the Avery Fisher Prize (2001), Musical America’s Instrumentalist of the Year award (2002), the Avery Fisher PrizeDeutscher Schallplattenpreis (2002, 2003), the Kennedy Center Gold Medal in the Arts (2010), the Mellon Mentoring Award (2012). In 2007 Midori was named a United Nations Messenger of Peace. In 2012, she received the prestigious Crystal Award by the World Economic Forum in Davos for "20-year devotion to community engagement work worldwide". In May of 2021 she will be an honoree of the 43rd Kennedy Center Honors. |

BD: Something, or someone?

BD: Something, or someone? Midori: Yes. It also depends on

how you’re feeling. You feel different every day. Let’s say

that the music expresses something sad, but there’s different kinds of

sadness, and every day you have different kinds of sadness. Or, on

the contrary, you have different kinds of happiness. So, I’m always

looking at the score and trying to find out what the composer meant to do,

or what he really wanted to do. Or, just by looking carefully into

the score, sometimes it opens your eyes. So, in that sense I look

into the score and look for new things. But I don’t look at the score

saying, “Okay, what should I say here?” That comes very naturally

through the music.

Midori: Yes. It also depends on

how you’re feeling. You feel different every day. Let’s say

that the music expresses something sad, but there’s different kinds of

sadness, and every day you have different kinds of sadness. Or, on

the contrary, you have different kinds of happiness. So, I’m always

looking at the score and trying to find out what the composer meant to do,

or what he really wanted to do. Or, just by looking carefully into

the score, sometimes it opens your eyes. So, in that sense I look

into the score and look for new things. But I don’t look at the score

saying, “Okay, what should I say here?” That comes very naturally

through the music. BD: It just turns out to be five or

six hours?

BD: It just turns out to be five or

six hours? BD: How do you divide your career between

solo recitals and concertos?

BD: How do you divide your career between

solo recitals and concertos? BD: You say you’re going to be recording

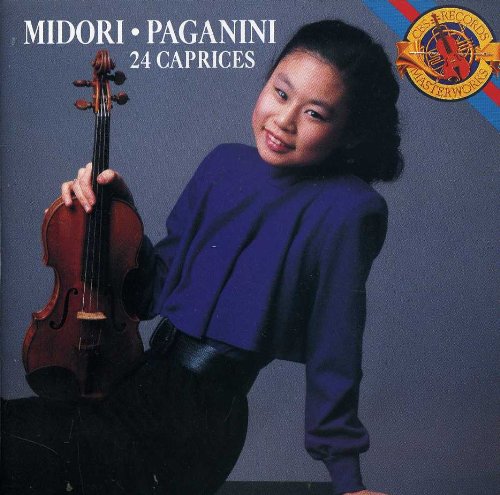

the Bach unaccompanied works. You’ve already recorded the Paganini

unaccompanied Caprices. Is there anything special about playing

unaccompanied?

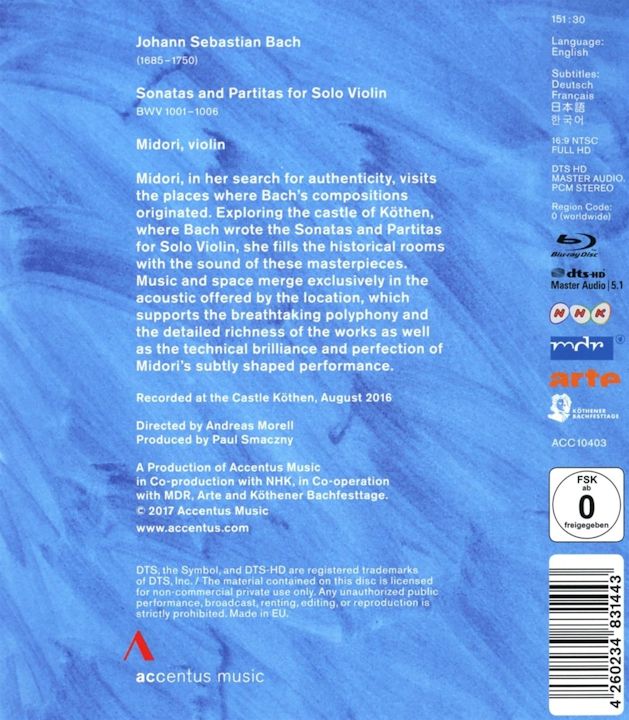

BD: You say you’re going to be recording

the Bach unaccompanied works. You’ve already recorded the Paganini

unaccompanied Caprices. Is there anything special about playing

unaccompanied? Midori:

I’m a permanent resident. I have a green card, which means that

I could become a citizen after a couple of years if I apply.

Midori:

I’m a permanent resident. I have a green card, which means that

I could become a citizen after a couple of years if I apply. BD: It responds well to you?

BD: It responds well to you?© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 6, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.