Shulamit Ran, (שולמית רן), born October 21, 1949

in Tel Aviv, Israel, began setting Hebrew poetry to music at the

age of seven. By nine she was studying composition and piano with some

of Israel’s most noted musicians, including composers Alexander Boskovich

and Paul Ben-Haim, and within a few years she was having her works

performed by professional musicians and orchestras. As the recipient

of scholarships from both the Mannes College of Music in New York and

the America Israel Cultural Foundation, Ran continued her composition

studies in the United States with Norman Dello-Joio. In

1973 she joined the faculty of University of Chicago, where she is now the

Andrew MacLeish Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Music.

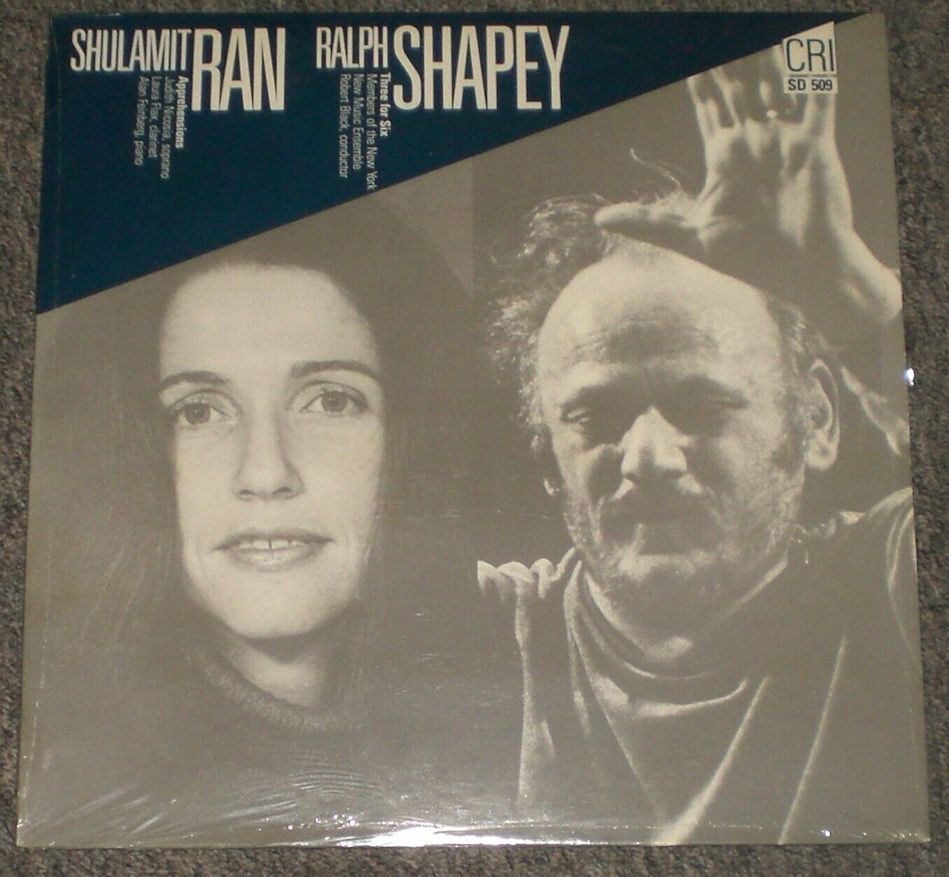

She lists her late colleague and friend Ralph Shapey, with whom

she also studied in 1977, as an important mentor.

In addition to receiving the Pulitzer Prize in 1991, Ran has been awarded most major honors given to composers in the U.S., including two fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, grants and commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation at the Library of Congress, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Fromm Music Foundation, Chamber Music America, the American Academy and Institute for Arts and Letters, first prize in the Kennedy Center-Friedheim Awards competition for orchestral music, and many more.

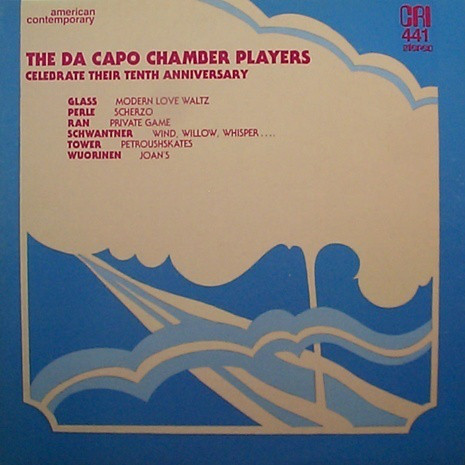

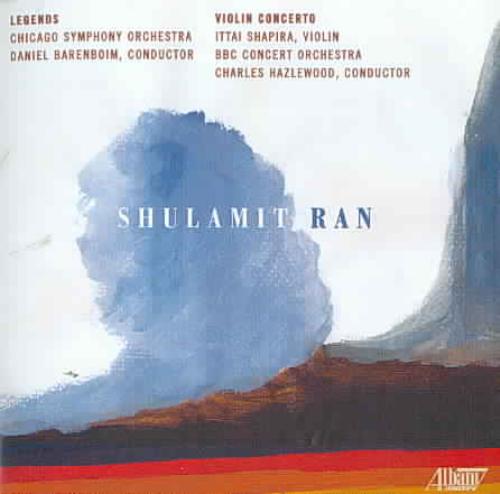

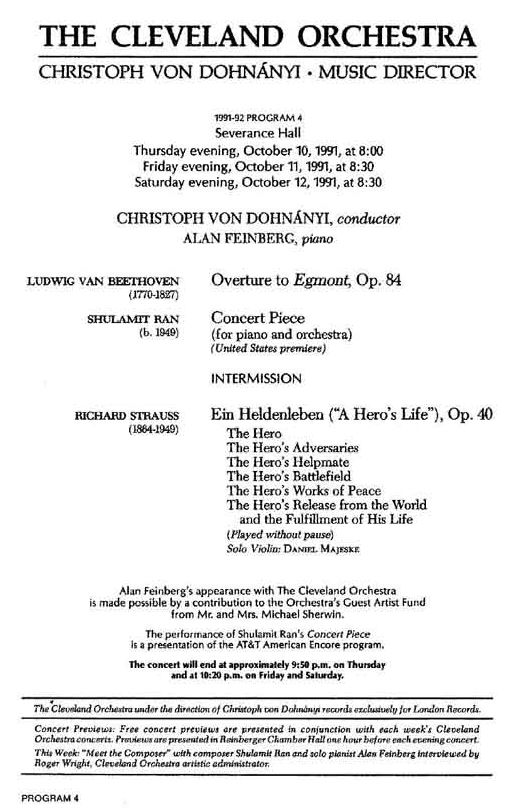

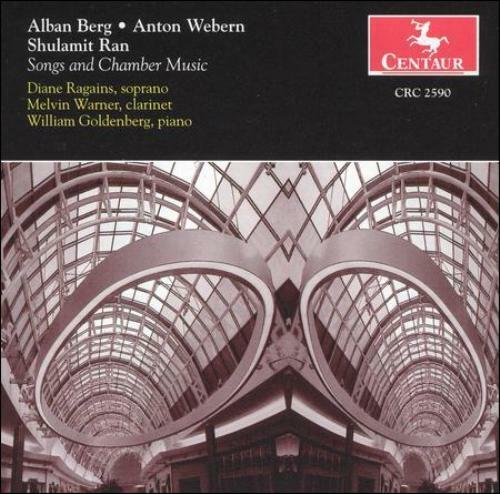

Her music has been played by leading performing organizations including the Chicago Symphony under both Daniel Barenboim and Pierre Boulez, the Cleveland Orchestra under Christoph Von Dohnányi in two U.S. tours, the Philadelphia Orchestra under Gary Bertini, the Israel Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta and Gustavo Dudamel, the New York Philharmonic, the American Composers Orchestra, The Orchestra of St. Luke’s under Yehudi Menuhin, the Baltimore Symphony, the National Symphony (in Washington D.C.), Contempo (the Contemporary Chamber Players) at the University of Chicago under both Ralph Shapey and Cliff Colnot, the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, the Jerusalem Orchestra, the vocal ensemble Chanticleer, and various others. Chamber and solo works are regularly performed by leading ensembles in the U.S. and elsewhere, and recent vocal and choral ensemble works have been receiving performances internationally.

Between 1990 and 1997 she was Composer-in-Residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, having been appointed for that position by Maestro Daniel Barenboim as part of the Meet-The-Composer Orchestra Residencies Program. Between 1994 and 1997 she was also the fifth Brena and Lee Freeman Sr. Composer-in-Residence with the Lyric Opera of Chicago, where her residency culminated in the performance of her first opera, “Between Two Worlds (The Dybbuk)." She was the Paul Fromm Composer in Residence at the American Academy in Rome, September-December 2011.

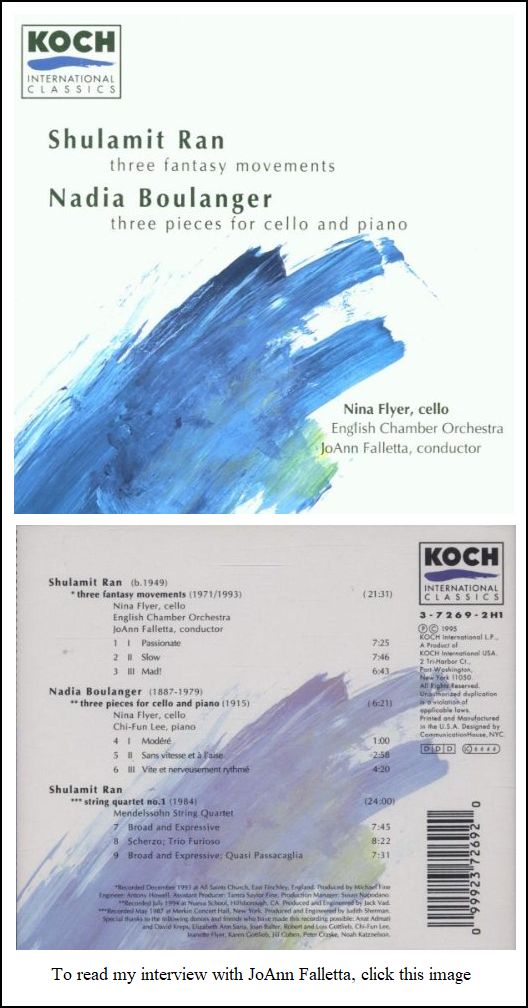

Ran served as Music Director of “Tempus Fugit," the International Biennial for Contemporary Music in Israel in 1996, 1998 and 2000. Since 2002 she is Artistic Director of Contempo (Contemporary Chamber Players of the University of Chicago). In 2010 she was the Howard Hanson Visiting Professor of Composition at Eastman School of Music. Shulamit Ran is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, where she was Vice President for Music for a 3-year term, and of the American Academy of Arts and Science. The recipient of five honorary doctorates, her works are published by Theodore Presser Company and by the Israeli Music Institute, and recorded on more than a dozen different labels.

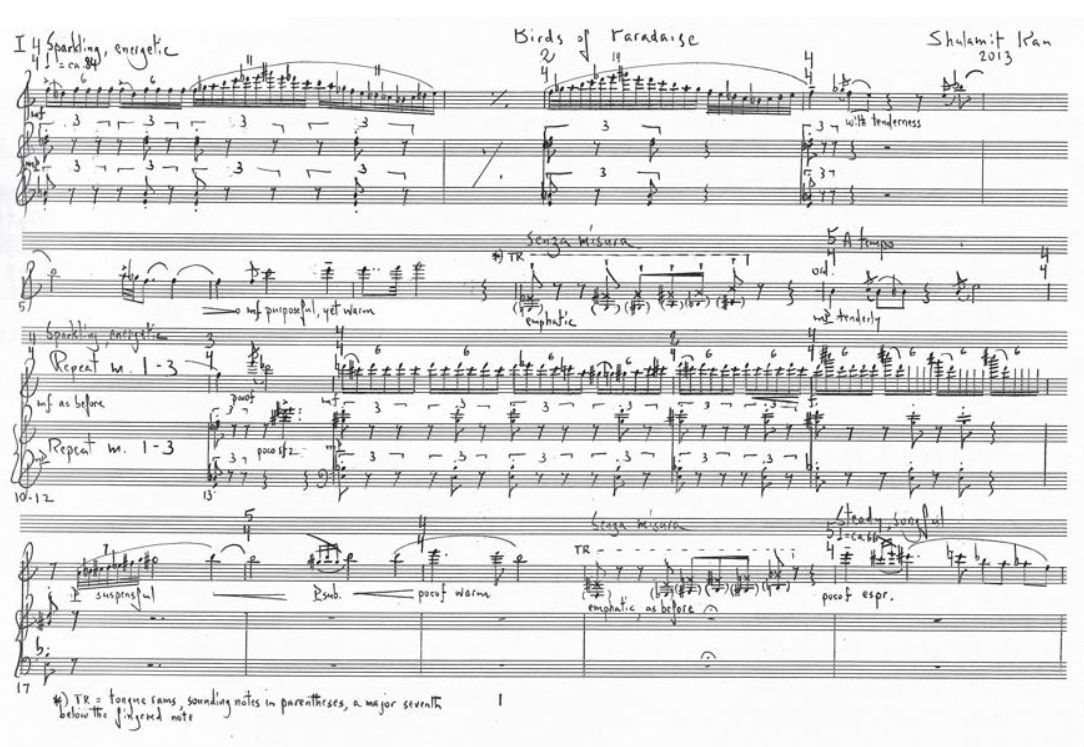

Glitter, Doom, Shards, Memory, String Quartet

No. 3, was commissioned by Music Accord, a consortium of concert presenters

in the U.S. and abroad, for Pacifica Quartet, and received its first

performance in June 2014 in Tokyo.

Born in Israel and trained in New York, she

has spent most of her creative life in Chicago, both at the University

of Chicago, and with our two world-class performing entities

— the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Lyric Opera

of Chicago. It has been my great pleasure to have heard her music

performed by both of these groups. It has also been my privilege

to have interviewed her twice — at the

end of 1994, and in the middle of 1997. The first was a general conversation,

the usual one that I did with most composers. The second was designed

specifically to promote her just-completed opera Between Two Worlds

(The Dybbuk).

Born in Israel and trained in New York, she

has spent most of her creative life in Chicago, both at the University

of Chicago, and with our two world-class performing entities

— the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Lyric Opera

of Chicago. It has been my great pleasure to have heard her music

performed by both of these groups. It has also been my privilege

to have interviewed her twice — at the

end of 1994, and in the middle of 1997. The first was a general conversation,

the usual one that I did with most composers. The second was designed

specifically to promote her just-completed opera Between Two Worlds

(The Dybbuk). BD: When you are starting a piece, are you aware of

how long it will take to perform it once it’s finished?

BD: When you are starting a piece, are you aware of

how long it will take to perform it once it’s finished?

BD: [Still being ever hopeful] But

I would think those problems would pale in comparison to just getting

the piece experienced.

BD: [Still being ever hopeful] But

I would think those problems would pale in comparison to just getting

the piece experienced. BD: Do you purposely hide things

in there, or is that just the way it comes out?

BD: Do you purposely hide things

in there, or is that just the way it comes out? BD: Sure!

BD: Sure!  BD: When you’re recommending pieces

for the Symphony to play, how do you decide which kinds of things you’re

going to recommend? What kinds of things

do you look for in those pieces?

BD: When you’re recommending pieces

for the Symphony to play, how do you decide which kinds of things you’re

going to recommend? What kinds of things

do you look for in those pieces? SR: There were several things that

I had had in my mind, several possibilities that I was playing with,

and the particular situation with the Lyric, and their Center for American

Artists, made it possible for me to actually decide, which was good.

It was healthy to be put in a position that I had to really make

up my mind and get going. But you asked about the matter of commissions.

There have been things in my life that were good, and probably the most

interesting case was ten years ago, when I was approached by the Eastman

School of Music for a commission for Jan DeGaetani, the great, great

singer whom we all miss so terribly. She really was such a great

singer, a great human being. She was somebody at the time I did

not know personally, but I loved her singing. There were certain

pieces, for example, George

Crumb’s Ancient Voices for Children, and various other

works that were written for her, which she premiered, which, to me, were

really the epitome of what gorgeous vocal music of our time should be.

I always felt there was one person that I would want to write for,

and of all the performers, no matter what instrument, it would be Jan DeGaetani.

So, when I was approached by Eastman, where she was on the faculty, and

was asked if I would write for her, of course I leapt at the opportunity.

The commission was for Jan De Gaetani, oboe alternating with English Horn,

viola da gamba, and harpsichord... [looking intently at the interviewer]

and you’re making a face!

SR: There were several things that

I had had in my mind, several possibilities that I was playing with,

and the particular situation with the Lyric, and their Center for American

Artists, made it possible for me to actually decide, which was good.

It was healthy to be put in a position that I had to really make

up my mind and get going. But you asked about the matter of commissions.

There have been things in my life that were good, and probably the most

interesting case was ten years ago, when I was approached by the Eastman

School of Music for a commission for Jan DeGaetani, the great, great

singer whom we all miss so terribly. She really was such a great

singer, a great human being. She was somebody at the time I did

not know personally, but I loved her singing. There were certain

pieces, for example, George

Crumb’s Ancient Voices for Children, and various other

works that were written for her, which she premiered, which, to me, were

really the epitome of what gorgeous vocal music of our time should be.

I always felt there was one person that I would want to write for,

and of all the performers, no matter what instrument, it would be Jan DeGaetani.

So, when I was approached by Eastman, where she was on the faculty, and

was asked if I would write for her, of course I leapt at the opportunity.

The commission was for Jan De Gaetani, oboe alternating with English Horn,

viola da gamba, and harpsichord... [looking intently at the interviewer]

and you’re making a face! SR: That’s so hard to answer.

I really don’t know. I am a firm believer that the music one

writes is ultimately a reflection of one’s life, and one’s existence...

even though I don’t really believe in a one-to-one relationship in

the sense that if I get up in the morning and I’m in a bad mood, or

somebody’s called me up and said something that I wasn’t looking forward

to hearing, then I’m going to be writing angry music. No, I

don’t believe that’s the way it actually happens. A piece has

its own life, so to speak, and you can dream it particularly well if

the stimuli that happens at the time you are composing is helpful.

But in a much broader sense, everything that you are, everything

that happens to you, everything that your life is about does make its

way into your music. So, I suspect that my life would be very

different if I was not involved with the University. It’s not

just teaching, it’s the involvement with people, with students, with

colleagues, and an institution. There are so many facets to it.

Life would be different, and probably ultimately that would show itself

in my music. I don’t know in which way, but I’m sure it would have

some effect.

SR: That’s so hard to answer.

I really don’t know. I am a firm believer that the music one

writes is ultimately a reflection of one’s life, and one’s existence...

even though I don’t really believe in a one-to-one relationship in

the sense that if I get up in the morning and I’m in a bad mood, or

somebody’s called me up and said something that I wasn’t looking forward

to hearing, then I’m going to be writing angry music. No, I

don’t believe that’s the way it actually happens. A piece has

its own life, so to speak, and you can dream it particularly well if

the stimuli that happens at the time you are composing is helpful.

But in a much broader sense, everything that you are, everything

that happens to you, everything that your life is about does make its

way into your music. So, I suspect that my life would be very

different if I was not involved with the University. It’s not

just teaching, it’s the involvement with people, with students, with

colleagues, and an institution. There are so many facets to it.

Life would be different, and probably ultimately that would show itself

in my music. I don’t know in which way, but I’m sure it would have

some effect.

BD: Your opera is called Between

Two Worlds (The Dybbuk). What are ‘the two worlds’ we are between?

BD: Your opera is called Between

Two Worlds (The Dybbuk). What are ‘the two worlds’ we are between? SR: When dealing with text, but

not in an operatic sense, my feeling was that if you want to understand

each and every word, the time to acquaint yourself with the poetry is

before or after. During the performance, you should just try to

embrace the total result, and try to take in the emotional impact that

the work is leaving, regardless of whether you catch each and every word.

However, it’s a little different when you’re dealing with a plot,

and you’re observing one scene moving into the next, where one might be

engulfed by the proceedings as they occur.

SR: When dealing with text, but

not in an operatic sense, my feeling was that if you want to understand

each and every word, the time to acquaint yourself with the poetry is

before or after. During the performance, you should just try to

embrace the total result, and try to take in the emotional impact that

the work is leaving, regardless of whether you catch each and every word.

However, it’s a little different when you’re dealing with a plot,

and you’re observing one scene moving into the next, where one might be

engulfed by the proceedings as they occur.