| Donald Grantham was born November 9, 1947 in

Duncan, Oklahoma. After receiving a Bachelor of Music from the University

of Oklahoma, he went on to receive his MM and DMA from the University of

Southern California. For two summers he studied under famed French composer

and pedagogue, Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory in France. He

currently teaches music composition at the University of Texas at Austin

Butler School of Music, where he is the Frank C. Erwin, Jr. Centennial Professor

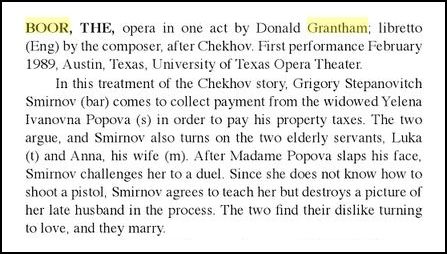

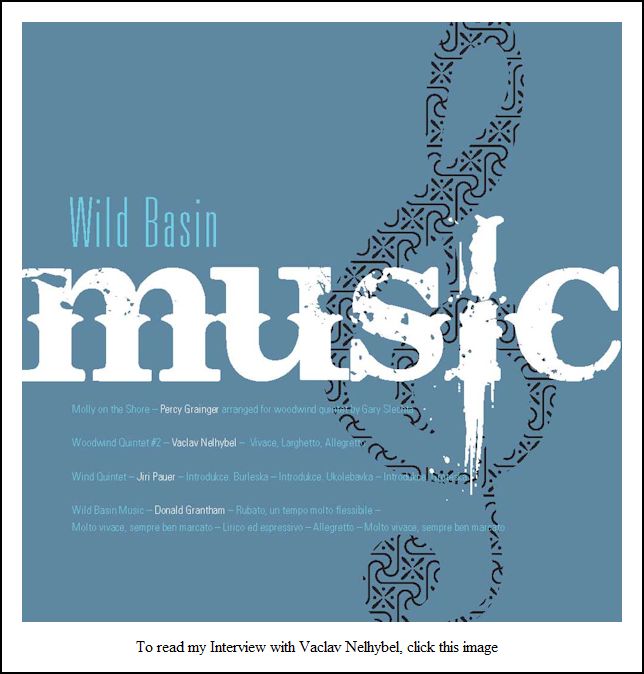

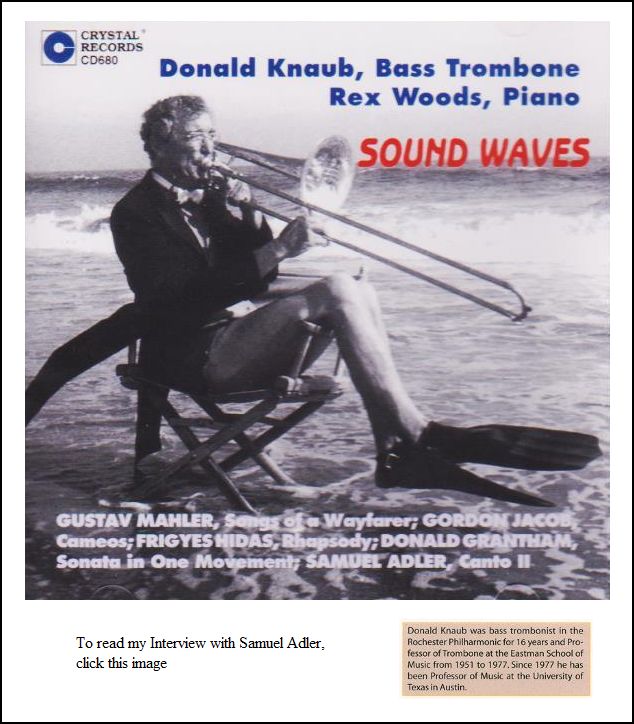

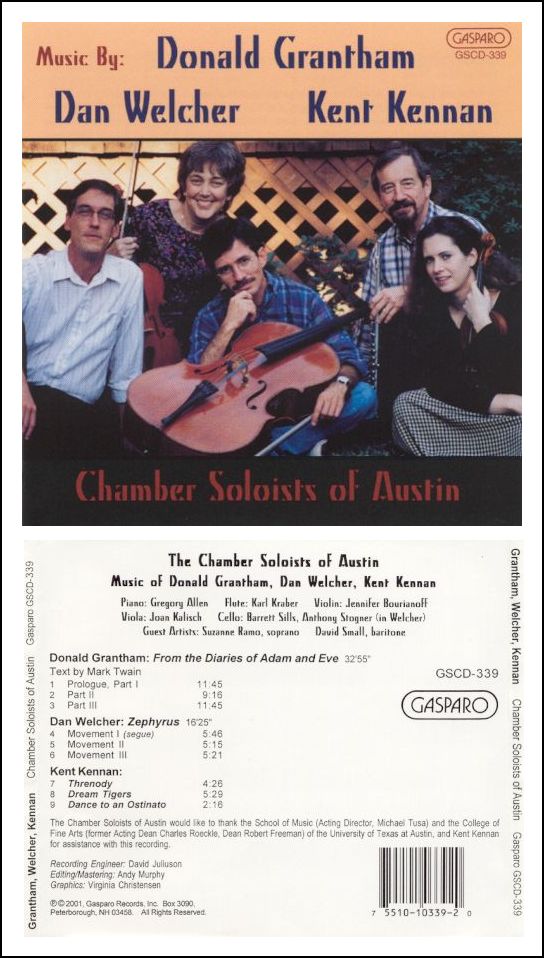

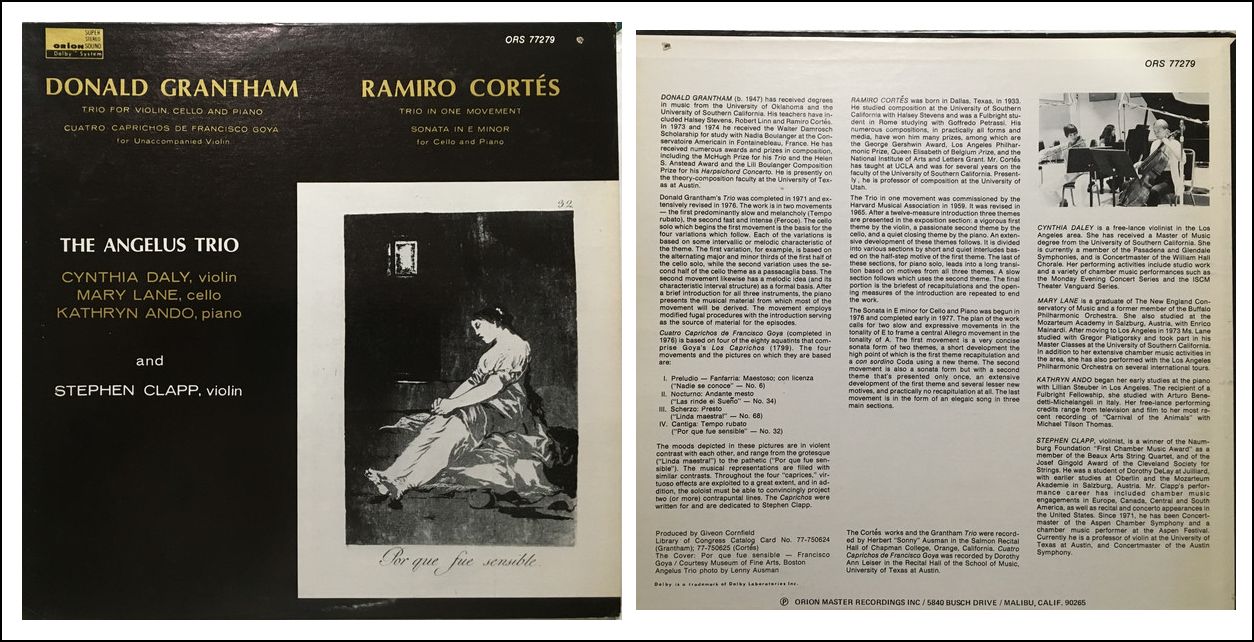

of Music. Grantham is the recipient of numerous awards and prizes in composition, including the Prix Lili Boulanger, the Nissim/ASCAP Orchestral Composition Prize, First Prize in the Concordia Chamber Symphony's Awards to American Composers, a Guggenheim Fellowship, three grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, three First Prizes in the NBA/William Revelli Competition, two First Prizes in the ABA/Ostwald Competition, and First Prize in the National Opera Association's Biennial Composition Competition. His music has been praised for its "elegance, sensitivity, lucidity of thought, clarity of expression and fine lyricism" in a Citation awarded by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In recent years his works have been performed by the orchestras of Cleveland, Dallas, Atlanta and the American Composers Orchestra among many others, and he has fulfilled commissions in media from solo instruments to opera. His music is published by Piquant Press, Peer-Southern, E. C. Schirmer and Mark Foster, and a number of his works have been commercially recorded. The composer resides in Austin, Texas and is Professor of Composition at the University of Texas at Austin. With Kent Kennan he is co-author of The Technique of Orchestration (Prentice-Hall). -- Throughout this page, names which are links

refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Here

is what was said at that time . . . . . . . . .

Here

is what was said at that time . . . . . . . . . BD: You don’t sing a sad song fast?

BD: You don’t sing a sad song fast?  DG: No, it

was it’s the fifth performance and second production.

DG: No, it

was it’s the fifth performance and second production.  DG: I’ve been very fortunate at the University of Texas.

I teach orchestration and composition, and then nine to twelve individual

students. I’ve been able to do all my teaching in the afternoons,

and have the mornings completely free for composition. So I manage

to get quite a bit written in that length of time. As matter of

fact, I don’t know that I would be able to spend a great deal more time

composing than the time I have available. I reach a point of diminishing

returns after a few hours and need to get away from it.

DG: I’ve been very fortunate at the University of Texas.

I teach orchestration and composition, and then nine to twelve individual

students. I’ve been able to do all my teaching in the afternoons,

and have the mornings completely free for composition. So I manage

to get quite a bit written in that length of time. As matter of

fact, I don’t know that I would be able to spend a great deal more time

composing than the time I have available. I reach a point of diminishing

returns after a few hours and need to get away from it.  BD: At about what time do you pick those works which

are the pieces you’ll keep in the catalogue?

BD: At about what time do you pick those works which

are the pieces you’ll keep in the catalogue?  BD: How do you make sure your pieces

don’t have worms in them?

BD: How do you make sure your pieces

don’t have worms in them?  BD: Is composing fun?

BD: Is composing fun? Also, see my interview with Robert Beaser

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 16, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1997. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.