Composer Jennifer Higdon

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Born in Brooklyn, N.Y., but raised

in the South, Jennifer Higdon received a Bachelor of Music from Bowling

Green State University in Ohio, a Diploma from the Curtis Institute of Music

in 1988, and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. In addition

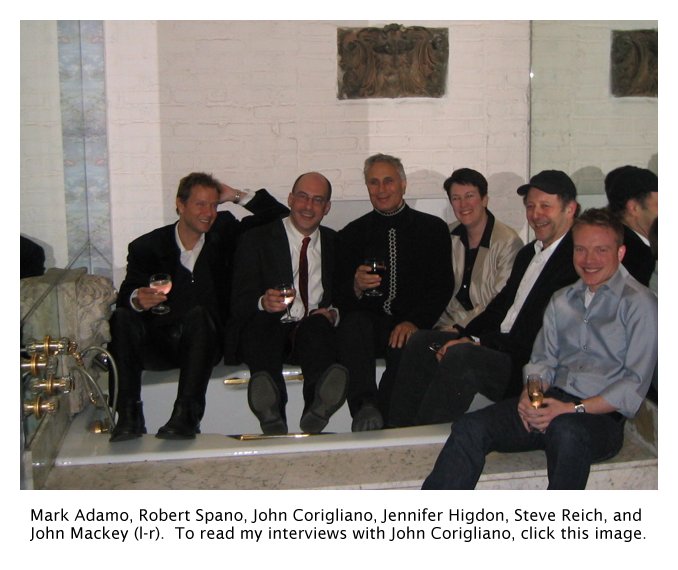

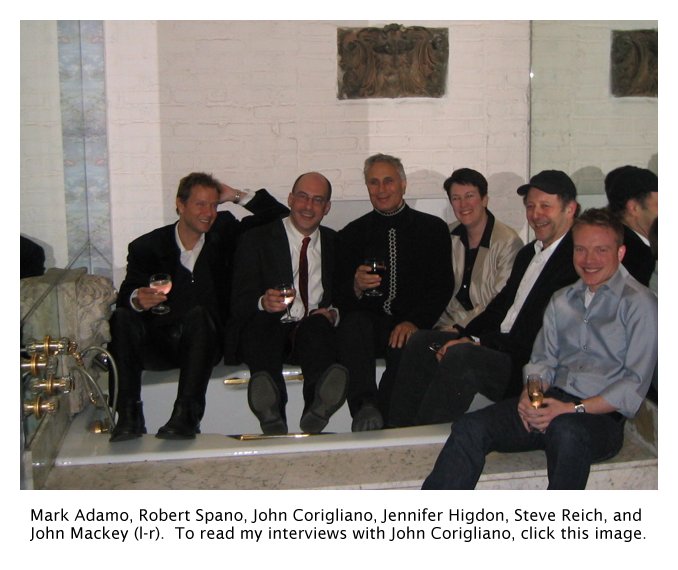

she has studied conducting with Robert Spano and flute

with Judith Bentley. She joined the faculty of the Curtis Institute in 1994.

She is the recipient of the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Music for her Violin Concerto, a 2009 Grammy Award

(Best New Contemporary Classical Recording) for her Percussion Concerto, a Guggenheim Fellowship,

Pew Fellowship, a Koussevitzky Fellowship, and awards from the American

Academy of Arts and Letters.

Her works are performed around the world, with commissions coming from

a variety of ensembles and individuals, such as the Philadelphia and Cleveland

orchestras; St. Paul Chamber Orchestra; Gary Graffman; Hilary Hahn; the

President's Own Marine Band; Tokyo String Quartet; Time for Three; Philadelphia

Singers; Mendelssohn Club; eighth blackbird; and Opera Philadelphia and

Santa Fe Opera.

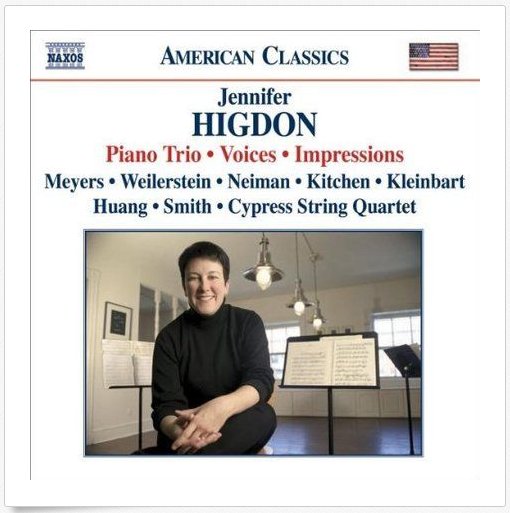

She has works on more than four dozen recordings, including the Grammy-winning

Higdon: Concerto for Orchestra/City

Scape.

-- Biography adapted from the

Curtis Institute website

-- Names which are links (both here and below) refer to my interviews

elsewhere on this website. BD

|

It is always interesting to catch someone early in their career, especially

when the promise of youth blossoms into full-blown success. I met

Jennifer Higdon on Valentine’s Day

of 2004, when she was in Chicago for a performance of one of her chamber

pieces on the MusicNOW series, which is an adjunct of the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra and includes some of their members along with a few guests.

Her career was well on its way even then, and it got an additional boost

in 2010 when she won the Pulitzer Prize. Since that time, she

has continued apace, with performances and recordings in significant numbers.

So this conversation reflects her as she begins to blossom, and shows,

perhaps, how she emerged to the success she is today.

Throughout our conversation, she was bubbling with enthusiasm and showed

a kind of self-amazement about the whole business.

Here is that encounter . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie:

You mentioned that you were starting to write something for junior high band.

Is it particularly difficult to write something interesting that is not

technically challenging?

Jennifer Higdon:

Actually it is much harder than writing for professional groups, I have to

say. I was just talking to Gusty [Augusta Read Thomas]

about how difficult that is; the limitations are extraordinary. The

kids only have very small ranges on their instruments, and moving into anything

with sixteenth notes is a problem. I’m sure they feel it’s interesting,

but when you compose a lot of music you’re always trying to make it sound

interesting. But what’s interesting to me and what’s interesting to

them are two different things! [Laughs]

BD: Is it your

responsibility to make it interesting to them, or is it your responsibility

to make something that will become interesting?

JH: Actually, probably both. That’s a good

question. It’s funny; the whole idea behind this Band Quest series

is that they’re trying to get established composers — people

like Chen Yi and Michael

Daugherty — who normally writes orchestra music to try writing something

for band, but something that will communicate to a much younger group.

It is really amazing how difficult it is because you write something, you

look at it, and you wonder if it is going to work, or if they can play it.

To me it looks simple, but I realize with all the training that we go through,

it’s a different prospect for a junior high group! [Laughs]

Oh, boy, is it!

JH: Actually, probably both. That’s a good

question. It’s funny; the whole idea behind this Band Quest series

is that they’re trying to get established composers — people

like Chen Yi and Michael

Daugherty — who normally writes orchestra music to try writing something

for band, but something that will communicate to a much younger group.

It is really amazing how difficult it is because you write something, you

look at it, and you wonder if it is going to work, or if they can play it.

To me it looks simple, but I realize with all the training that we go through,

it’s a different prospect for a junior high group! [Laughs]

Oh, boy, is it!

BD: In general

you get a lot of commissions. How do you decide, yes, I will to do

this one or no, I will turn that one aside.

JH: Totally

gut instinct. It actually is completely gut instinct; just what sounds

like it might be interesting to work on. It has no logic. I have

to say when a really good group — like the Philadelphia

Orchestra — comes to you and they say, “We want to

commission you,” of course your brain goes oh yeah! [Both laugh]

There’s not much thinking in that. But you do have to learn to balance

it, because this past year I went through eleven commissions, which is a

lot.

BD: That’s almost

one a month.

JH: That’s about

right, and that was a little too many. I said no to a lot of projects,

but things kept coming up that just sounded so interesting that I couldn’t

say no.

BD: I would

assume it takes you more than a month to do each commission?

JH: Yes, but

it depends on the piece. Some of the commissions were for shorter works.

I had this commission for the Gilmore Piano Festival, and I guess they were

little short snippets. It was based on the idea of the theme of the

Goldberg Variations by Bach, and

they wanted everyone to do a variation. So something like that is

very different than writing a full piece. I wrote two string quartets

and a piano trio this year. One of the string quartets was thirty

minutes, so that took a couple of months. In the month that I did

actually the Gilmore piece, I think I did two other short pieces.

So they kind of bunch up, but some of them take longer.

BD: You

work on more than one piece at a time?

JH: No, I don’t.

I’m always thinking ahead. That’s what it is. In the actual

writing process I’m only working on one, but my brain is processing the

next piece down the road.

BD: I would

think it would be good, though, to have the next piece in mind, so that

if you come up with an idea that doesn’t work in this piece it might go in

the next piece or the piece after that.

JH: Absolutely,

absolutely. I find my brain works out details while I’m working on

piece A that I know will be okay, for piece B. You start just thinking

of a piece down the road. And then I always keep notebooks for it,

because I generally know a couple of years in advance what I’m going to be

working on. I’m always keeping notes. I have insomnia or something.

I’ve noticed the past couple of nights I have not been able to sleep as well.

One of the pieces that’s two or three pieces down the road for me is for

bass-baritone and orchestra for the Brooklyn Phil. I’m not sure who’s

conducting, but Robert Spano is the one who had asked me to write it, and

I’ve been coming up with ideas in the insomniac hours... one a.m. [Laughs]

BD: As someone

who worked night for years, I’m glad to welcome you aboard!

JH: Yes.

It’s a good creative time.

BD: Absolutely,

and it’s very quiet.

JH: Absolutely,

yes. It’s pretty amazing.

BD: You don’t

have to mention the name, but do you know the singer?

JH: Yes, actually.

It’s Eric Owens.

BD: Is it better

to know which singer will be doing it?

JH: Yes.

I like to know the ensembles, the musicians I’m writing for, or if I can

get to know the individual musicians and the singer. I know Eric from

Curtis. He went to Curtis there, and I saw him last year doing John Adams’

El Nino in Atlanta. Eric and

I talk occasionally and I thought, wow, what a voice he has! Brooklyn

requested Whitman texts because it’s an anniversary, and Whitman has such

a connection to Brooklyn. So somehow Eric seemed very logical.

I don’t know, for Whitman it seemed just his voice type.

BD: When you

write for a specific voice, that doesn’t preclude it from other voices or

other artists?

JH: No.

I get that question a lot because my Concerto

for Orchestra, which was written for Philadelphia, was so tailored

for the orchestra. But nine other orchestras have done it. People

have been asking what it’s like hearing Dallas do

it, or Milwaukee, and it is different, but it works. It does work.

BD: So there’s

lots of right ways?

JH: Yes.

It’s kind of funny... A lot of composers feel there’s only one way

to do it, but I’m interested in hearing everyone’s interpretation.

I really am. I find them fascinating. Sometimes people do things

very differently than what I had written, but if they can do it in a convincing

way, I’m with them.

BD: Are there

ever times that you want to go back and revise the score, incorporating these

new little discoveries?

JH: Actually I have done that before, especially

with tempos. It’s interesting with tempos; it really changes from

ensemble to ensemble and from hall to hall. I’m amazed at how much

it changes. When I play my own pieces, I change the tempos, too, so

I don’t hold anyone to them strictly! [Laughs] I tell musicians

that, because they always ask. They ask if I mind, and I say, “Oh,

no. I’m changing my tempos all the time.”

JH: Actually I have done that before, especially

with tempos. It’s interesting with tempos; it really changes from

ensemble to ensemble and from hall to hall. I’m amazed at how much

it changes. When I play my own pieces, I change the tempos, too, so

I don’t hold anyone to them strictly! [Laughs] I tell musicians

that, because they always ask. They ask if I mind, and I say, “Oh,

no. I’m changing my tempos all the time.”

BD: How much

stretch is there before it gets to be too much and it’s no longer your piece?

JH: That’s a

good question. I have heard those moments where they stretch like rubber

into something else that I’m not recognizing. That usually happens

with less experienced musicians who actually need to take it more slowly

because my stuff actually looks deceptively easy on the page, but it’s pretty

hard. Some of the players were saying this won’t be hard at first,

but then they start putting it together. It’s got its own challenges.

BD: But you

don’t write it to be hard?

JH: No, I don’t.

I’m writing it to just be musical and interesting, whatever my quirky rhythm

thing might be. It sounds very natural to me, but I know for everybody

else — seeing so many people struggle with the pieces — I

always know where they’re going to have problems. There are certain

rhythmic things that occur that I think makes the pieces difficult.

BD: Do you ever

think about revising the rhythm a little bit, to get the same idea a little

technically easier?

JH: To me, when

it comes to the rhythm it feels like it would be compromised in the piece.

I know it sounds kind of weird, and believe me, I know. I’ve had to

play my own pieces, and I’ve thought, “Oh, my gosh!

What the heck was I thinking?” But people always

say, “You can’t complain. You’re the one who wrote it!” [Laughs]

And it is interesting to watch. I don’t have any pieces that haven’t

been played again. They all get done quite a bit, so it means I’m

able to follow kind of the history of a piece. It is interesting to

watch the different players take it up, and hear what they do with it.

I find it completely fascinating.

BD: Do you view

all of these pieces as little children that are out making their own way?

JH: Yes, and

the older the child is, the less it seems attached to me. Do you know

what I mean? I‘ve got a flute quartet from 1988 that gets done all the

time, and that was so long ago, it seems, I can’t even remember writing it.

It’s amazing.

BD: But you’re

pleased that it’s out there?

JH: Yes, oh

absolutely, yes. The piece works really well for four flutes, if you

can imagine that combination. It’s not your every day typical string

quartet situation, but...

BD: Is it four

C flutes, or four different flutes?

JH: Four C flutes.

BD: I would

assume it would be piccolo, C flute, alto flute and bass flute.

JH: Yes, I know.

That’s why I decided to do four C flutes. A lot of flute quartets

are mixed flutes, but I decided to write a really intense piece with very

close intervals, so the four C flutes work really well. That piece

gets done all the time. It sometimes shocks me how much that piece

is done.

BD: If it has

become a challenge, perhaps if you can do that piece then you’ve really

made it as a flute quartet.

JH: A lot of

college groups will do it, and there will be individual students who are doing

it for their junior or senior recital and want to play something with their

friends. The piece has a lot of bite to it. I’ve played three

of the four parts, and it is fun to play. I call it my atomic roller coaster

ride. It moves at a real serious clip and it has these really complex

rhythms. It’s only about four minutes long, but man, it’s a ride!

It’s a ride and a half. Yeah, it’s fun.

BD: A really

short ride and a really fast one?

JH: Very intense,

yes. It does have that feeling to it. Often I love watching

the audience, because they’re often like, “Oh, my gosh!” I’ve got

the flutes high up, playing minor seconds, which is just...

BD: Ooooooh!

JH: Yes, exactly.

[Both laugh] Exactly, Bruce! You got it.

* *

* * *

BD: You write

these pieces for specific people or even general people. What do you

expect of the audience that is listening to it for the first time?

JH: I’m often

thinking about the audience. For me music has to communicate.

That doesn’t mean hit has to be a certain tonal language, but I’m constantly

thinking if this is the most effective way to talk to the audience.

So they are in the back of my mind. I usually think first of the performers,

because I know that I’m going to have to go through them to convey the message

to the audience. Having been a player myself in a lot of situations

where I’ve done new music, I know how hard it is sometimes. You want

to make sure the players are getting something from all the work they’re

putting into the piece. We’ve all played pieces before that we said,

“Ugh, I just worked 16 hours on that, and boy, it didn’t feel like it was

worth it.” So I do my best to make sure it’s a worthwhile musical experience.

BD: What is it that makes a piece of music

— either your music or other music — worthwhile?

BD: What is it that makes a piece of music

— either your music or other music — worthwhile?

JH: I often

think about that because there’s something I do instinctively pondering

this, and I’m always trying to figure out what that is. What is that

quality that makes it worthwhile? I’m always aware that people like

interesting lines. I often think about what it’s like for the people

who play the off-beats in Sousa marches. I have a couple of friends

who played in the President’s Marine Band, so they are always doing things

like that.

BD: The French

horns are always off the beat.

JH: I know!

I was talking to a French horn player just the other day about this very

thing. I’m very aware that every line I write, whether it’s the solo

or it’s some principal line, or maybe it’s just the background line, every

line has to be shaped to be interesting. It doesn’t matter how utilitarian

it is.

BD: And it still

has to be within the general shape of the whole piece.

JH: Exactly.

So you got a couple levels of architecture going on, basically. You

want make interest on the level of the individual part, but also fitting

in the context of the piece. So that’s the biggest thing, and also

making sure it fits well in the instrument. In other words, it’s comfortable.

Even though I’m challenging people to push themselves technically, it shouldn’t

be unplayable on the instrument or off-chord on the instrument. So

I’m forever going to musicians and saying, “Can you play this? Can you

play this?” I’m forever cornering the kids at Curtis and asking them,

“How does this fit? Is there a better way to finger it? Does

it sound okay?”

BD: Is it better

to go to the kids at Curtis, or would it be better to go to the Philadelphia

Orchestra?

JH: It’s the

same thing. [Both laugh] It actually is the same thing, and I

do corner some of the people in the Philadelphia Orchestra. But because

I teach at Curtis, it’s much easier to corner the kids at Curtis.

BD: I understand,

but a professional player who has been doing it for twenty or thirty years

might know a trick or something.

JH: Right.

It’s interesting, though, because the Curtis kids tend to be more open.

They don’t bring to the experience the bias like the orchestra members,

so I guess there’s pros and cons both ways. But because most of these

kids study with Philadelphia Orchestra members, I figure I’ve got myself

covered. [Both laugh] And then a lot of times if I’m writing

something for a younger group, I’ll actually go to someone who’s less experienced

because I need to know. They’re perspective is going to be really

different; it really is. So I think a lot about who I’m writing for.

It’s important.

BD: You were

talking about shaping the lines and shaping the big picture. When you

start out writing the piece, do you know the shape of the whole thing, or

does it take shape as you are writing?

JH: I usually

know pretty much what the shape is, and then the details work themselves out

as I am writing. I often start in the middle of a piece. I don’t

always start out at the beginning.

BD: You simply

know that this section belongs in the piece?

JH: Yes.

I have done a lot of sketching, and I’ve also ended up not using ideas.

Some pieces come to me that are very clear, and some pieces I’m a little

more in a fog. When I was writing this Philadelphia Orchestra piece,

the piece was so big! It was a thirty five minute piece, and it took

a tremendous amount of sketching to get the details worked out. But

when I wrote a piano trio a year ago, it was a lot more clear. Maybe

that was because it’s a much smaller piece; it’s only three instruments.

So every piece is a different degree. I don’t actually don’t use a

regular form. It’s all through-composed. That would be the technical

term for it, but I sometimes want to draw out things and find what the shape

is dramatically and where are things going to happen. Then I listen

to the music to see if I’m achieving that. If it goes against what

I’ve first come up with as an idea, I go with the music. I don’t follow

the graph or the drawing that I’ve written.

BD: Fifty years

from now, will the theory text say this is the Higdon Form?

JH: Golly, that’s

a scary thought! [Laughs] I hadn’t thought about that!

I guess it could be. Or they’ll ask what was she thinking? [Laughs]

I studied with George Crumb

at the University of Pennsylvania, and he told me, “The answer really is

always finally what you’re hearing. The true test is what you hear with

your ear.” So I thought to myself if that’s the final test, why don’t

I just start at that point? So I tend to follow my ear. I write

instinctively, which is impossible to explain because how do you explain

instinct? It used to make my teachers a little crazy, because school

is geared in the other direction; it’s geared in a theoretical study of form.

BD: Do you feel

that you are a part of any kind of musical lineage?

JH: Yes I’m

sure I am, but I have such a bizarre background leading up to my career

in classical music that I’m not actually sure. It’s been funny to

watch the press reviews. Everyone is trying to figure out where to

put me. The lists of composers the people are saying I’m like cracks

me up, because they are not related. One guy in the Washington Post mentioned four different

composers in review — Messiaen, Steve Reich, Lutosławski,

and Stravinsky.

BD: Oh my!

[Laughs]

JH: I’m like,

my gosh! That’s basically okay; we got an entire array of the twentieth

century here. That’s a lot of different styles, a lot of different

languages, a lot of different rhythm.

BD: That’s not

a line, that’s four corners.

JH: Exactly!

So we’re talking a huge picture, and I wondered what is he trying to get

at, what is it that he’s trying to find, what it is he’s hearing?

BD: Do you want

to fit into a line, or do you just want to just be you?

JH: I just want

to be me. That’s probably the more accurate description. I didn’t

grow up around classical music, so for me line probably doesn’t have as

much meaning, or I don’t feel the context I’m working in as much.

Maybe because I write so much music I’m always thinking how I can make this

piece better. I’m always focused on the music, and I never think about

historically what is happening. Maybe it’s better that way, though.

The weight of history might be a little bit of a daunting experience.

BD: Then the

obvious question is how did you get into it? Where did you come from,

and how did you get into the classical side?

JH: I grew up

listening to rock and roll. We didn’t have classical music around my

household. My dad was a commercial artist who worked at home, so he

always had the music of the 60s and 70s playing. Simon and Garfunkel,

The Beatles, Kingston Trio, a lot of reggae. This was before reggae

was hot. He had lots of those sorts of recordings. So, it was

probably folk and rock and Rolling Stones.

BD: So why aren’t

you the next Joan Baez?

JH: That’s an

interesting question. I’m not sure what happened.

BD: Does your

father say, “Where did she go wrong?”

JH: I know!

Yes, I am the black sheep of the family. Because I went into classical

music, I am completely, totally, the black sheep of the family because my

parents have been to a lot of rock concerts — probably

more rock concerts than classical music concerts. There just wasn’t

much classical music around.

BD: So is this

your rejection of their ideas?

JH: It might

be. It actually might be! I know it sounds really funny.

BD: Perhaps

that means there is hope for classical music because all of these parents

are listening to rock, but everybody can reject them and come back over to

our side!

JH: It’s true!

Its very interesting because it occurred to me at some point that I actually

come more from the musical background than most. I don’t mean, necessarily,

classical listeners, but anyone who listens to just music in general.

I come more from that background than I do from people who just listen to

classical because I didn’t grow up on it. A lot of people say they

think my rhythm is influenced. I’m having to listen to what other people

are saying because I’m too close to music to be able tell what is happening

that people are responding to. A lot of people think that my sense

of pulse and rhythm is probably from the amount of Beatles I listened to

growing up. I would have to say that probably was the biggest influence

for me. Every day of my childhood I must have listened to some sort

of Beatles recording, and I think that probably did influence me. But

how the heck did I get into classical music is really a good question!

BD: Does that

help your music speak to others who grow up that way?

JH: I think

so. I’m guessing that’s what’s happening. I’m not really sure.

I bet in ten years I probably can give you a clearer answer. It’s really

kind of funny. It would be an interesting perspective. This is

weird... I recently found a box of stuff from my childhood...

BD: Writings

or toys?

JH: They’re

drawings. I used to draw a lot. My brother and I used to draw

all the time. We just drew and drew, more than most kids, even beyond

the age when most kids stop. I found I had actually written, at age

six or seven, a classical music tune with a staff and a treble clef and

a melody. The melody had shape and form. I didn’t know anything

about classical, nothing at all about reading music or anything, so it makes

me wonder where that came from. I totally forgot about it, and just

recently I ran into it again. I’m looking and I thought, “My God, I

wrote this!”

BD: Are you

going to use it?

JH: That’s a

good question.

BD: It could

become Variations on my Childhood.

JH: [Laughs]

I might have to do that. So I realized something must have been in my head.

When I discovered that, I thought there’s no way a kid would be writing

this at six or seven years old with no background.” We had a flute

laying around the house and I always was aware of the power of music, but

I was always doing other creative things. My brother and I used to

make 8mm animated films. My Dad had an 8mm camera, and we used to do

like little claymation things. And I used to write a lot, literary

stuff. He and I used to draw and paint, so I was always doing those

sorts of artistic expressive things, the kinds of things kids normally do.

At some point I picked up this flute and taught myself to play, which, now

that I think about it, was a late start. At Curtis where I teach, everyone

started at age two. Everyone was a baby when they started. I

started teaching myself to play at fifteen. So I didn’t really get

any kind of musical instruction, and when I started college, at the age of

eighteen, I didn’t know the Beethoven symphonies. How many people do

you know who work in classical music didn’t know the Beethoven symphonies

at eighteen? Now that I’m saying it, it sounds completely ridiculous.

BD: But it gives

you a different perspective on the whole thing.

JH: It does,

and what I used to think was a disadvantage, I now think might have been an

advantage. It was pretty hard going through school because they expect

you to know that stuff. You have to have it, especially at the doctoral

level. People were passing the ‘drop-the-needle’

exams quickly, and I was trying to learn the stuff. So it may have

slowed me a little bit, but now I think it might have been an advantage.

BD: I would

think approaching a symphony late like that, with all of that experience,

will give you a whole different outlook.

JH: Different,

totally, and I feel like I’m still discovering this stuff. I didn’t

know piano trios before I wrote the piano trio last spring. People

kept saying, “Oh you’ve got to check out the Brahms. You’ve got to

check out the Fauré.”

BD: For you

a trio is piano, bass and drums.

JH: That’s it,

exactly! So I’m going to Tower Records and I’m buying trios.

I didn’t know a single solitary piano trio. It’s kind of neat having

the knowledge I have now to actually be able to explore these things.

I get really excited that I know it’s got to be totally different than for

my colleagues who have known those pieces since they were teenagers.

BD: This will

make a wonderful doctoral dissertation sometime to look at your trios from

a fresh perspective.

JH: Yes.

There’s a student actually in Philadelphia who is doing a doctoral dissertation

right now on a couple of my flute works. When I start thinking about

these things or when I do the interviews with people, I’m like, “Yeah, why

does that happen that way?” I have to really think about it.

But it’s such a bizarre beginning, it probably has really affected my whole

approach.

BD: With students

doing doctoral dissertations, does that make you feel old?

JH: Yes, it

does. It’s really strange. I keep wanting to say, “Are you kidding?

[Laughs] Are you crazy?” I mean, it’s totally funny, because

I realized the other day that I just graduated with my doctorate ten years

ago. I didn’t realize the proximity of this occurring. I’ve only

had one other person do a doctoral dissertation on one of my other flute

pieces. The flute players were aware of me before, because that’s the

early stuff that I was writing and the instrument I play.

BD: So, have

you had a good decade?

JH: It’s been

an amazing decade. I have had the most amazing ride, and the trajectory

has been unreal. I have to admit, I’m still trying to adjust; it’s

been moving at such a clip.

BD: Too fast?

JH: I don’t

know. Is it possible for it to be too fast? Ask me that in ten

years! [Laughs] It seems like a pretty joyous ride right now,

and I have to say, the level of performances! This year alone I have

maybe forty orchestra performances, and I’m averaging around 120 performances

a year.

BD: Wow!

JH: It’s a staggering

number.

BD: You must

be doing something right.

JH: I guess

so. I know. Really.

* *

* * *

BD: When you

write a piece of music, do you feel it should be for everyone?

JH: Can it be

for everyone? I’m writing for some people, and I know it won’t be for

everyone. My parents were so involved in experimental arts stuff when

I was growing up, that I got a chance to see a lot of good stuff but also

a lot of junk. I also came to realize early on that there’s no way that

everyone’s going to like what you do. There’s just no way. There

are a lot of things that I hear that I don’t care for, but I respect that

the person did it. So usually when I’m writing, it’s always with the

realization that this will work for some people and it won’t for others, and

that’s okay. It’s a little less stressful, looking at it that way.

Maybe it’s being the child of hippies in the sixties and seventies, and seeing

so many of these bizarre arts happenings. We were living in Atlanta

at the time, and really there was a lot of strange stuff going on. But

I got all of my experimenting out of my system early on. I swear, I

did! [Both laugh] I saw so many bizarre things and heard so many

bizarre musical ensembles that went with these experimental animation and

film festivals, that it kind of satiated my soul for that. So rather

than thinking about creating a new sound, I’m often thinking about just what’s

interesting and what will make something good.

BD: With all of these commissions, are there still

some pieces that you just want to write and have to get out of your system?

BD: With all of these commissions, are there still

some pieces that you just want to write and have to get out of your system?

JH: Fortunately,

the commissions have fit with that. Somehow it’s all jiving in my

head. People often ask if I ever write something just for myself,

but I have to admit I’ve been so fascinated with the commissions I’ve been

given, that I find those challenging and engaging enough that I haven’t felt

like I’m missing anything. About two years ago someone approached me

about doing a piece for orchestra and juggler. They were saying, “This

guy can actually play rhythmically. He can throw things and bounce

things.” I thought about it, and there was actually nothing appealing

about it! So I decided to pass on that.

BD: The only

thing I think of which is close to that would be the Morton Gould Tap Dance Concerto.

JH: Yes, exactly.

I think there is a typewriter piece I heard once [The Typewriter by Leroy Anderson] and

maybe some day that juggler thing will appeal, but I have to admit right

now, it doesn’t appeal in the least.

BD: We’re kind

of dancing around it, so let me ask the easy question straight out.

What’s the purpose of music?

JH: I think

it’s to express the human condition and really to express the soul.

I really do. It expresses the human condition on so many levels because

there are those angst pieces and there are those pieces that sound like

ecstatic joy. There are the relaxed pieces and there are the uptight

pieces. It’s such a perfect reflection of life and the soul, and yet

the people who are listening don’t have to know a thing about it.

Usually while I’m writing, that’s one of the things I think about.

I know there’s been a lot of debate in the twentieth century about the fact

that maybe people don’t understand it because they don’t know about this

or that type of music, but I have to say my approach is I don’t think you

should have to know anything about my music, or anything about music in

general, to enjoy it. It should still be an enjoyable experience.

But I look at music as a mirror. It’s a mirror of everyone, everything,

our society, people. I often think of it as a mirror of people, though.

I know some people think of it in terms of objects. I know Ravel used

to talk about factories all the time, and clock-making, but I often think

of it as people.

BD: Is your

music a mirror of you, or is all music a mirror of everybody?

JH: I think

all music’s a mirror of everyone. I don’t know what my music’s a mirror

of. It’s probably of other people, but there’s probably certain pieces

that are more a mirror of me.

BD: You’re not

using music as self-analysis, are you?

JH: Sometimes

it feels like self-analysis. About five and half years ago I lost my

younger brother. He passed away, and to compose in the years after that

was the most therapeutic thing. You can tell that there is something

about those pieces, so, self-therapy? Absolutely. It was easier

for me to get through the grieving process having music to express it.

Blue Cathedral on that Rainbow Body disc was written for my

brother. I was writing a lot of those pieces at that time and they

helped me deal with it tremendously. So it is kind of a self-analysis,

kind of a working it out in a way, but certain pieces of mine seem completely

like reflections of other people. Then other pieces feel like they

have more of me in them. It changes from piece to piece. That

keeps it interesting, at least.

BD: A number

of your pieces of yours have been recorded, and more and more are coming all

the time. Are you pleased with the recordings that have been made of

your works so far?

JH: Oh, yes,

absolutely. I’ve been really pleased. I’ve been so lucky to work

with superb musicians. I’ve had more than the normal share of spectacular

performances, and I have to say working with the Atlanta Symphony and Robert

Spano has been just an incredible experience.

BD: Spano was

your teacher for a while?

JH: Yes, for

a year. This was so funny. It was his first year out of Curtis,

and we bumped into each other in Bowling Green, Ohio, of all places.

So I’ve known him since ‘85! I had Conducting with him for a year

and it was amazing! It was incredible. He’s one of the best

teachers I’ve ever had.

BD: Does that

help you in getting your music looked at by his eyes?

JH: I don’t

know if it’s because of that, but neither one of us did anything about it.

He just started conducting my music four or five years ago. I had

never really sent him anything. I’m real shy about imposing on people.

I don’t know what it is. It’s so hard for me to go up to him and ask

him to look at something. I know him really well, so you would think

I would be a little more comfortable.

BD: But don’t

you find it better if the music stands or falls on its own merit, rather

than you pushing it?

JH: Yes, that’s

it exactly. My whole philosophy has been that the music needs to sell

itself, and no matter how much I’m going to pester people about it, they

don’t have time to look and listen to this stuff. If they’re interested,

they’ll ask. Robert came to my music, actually, even after we’ve known

each other after all this time, by a weird fluky thing. Blue Cathedral was commissioned by Curtis,

and he happened to be the conductor who was engaged to conduct that specific

Curtis Symphony Orchestra concert. It was completely accidental.

I’m not even sure the people who had scheduled them realized that we had

known each other. That’s when he started doing my music, and that was

in 2000, so it’s actually fairly recently.

BD: Obviously

he likes it. He must think these are good pieces.

JH: Yes, and

he commissioned something, actually. The disc that’s coming out in March

has Concerto for Orchestra, which

the Atlanta Symphony did an amazing job with! Also included is a piece

that they commissioned which is like a full-length symphony. So the

disc is all my music. Wow! It’s all my orchestra music, and that’s

big. It’s amazing!

BD: When you

get through with that, then, do you want to go back to a flute sonata?

JH: No, no flute

stuff. I’ve done enough of the flute stuff for a while!

BD: Well, something

for a solo instrument.

JH: Yes.

Actually, I have to say, I enjoy alternating the different things.

I don’t like doing a lot of one kind of thing. I like doing a string

quartet, then an orchestra piece, then an organ piece. I like mixing

it up.

BD: Right now

you’re composer in residence with a vocal group?

JH: Yes, the

Philadelphia Singers.

BD: What’s it

like working with the human voice?

JH: It’s great.

It’s totally different. My music is pretty virtuosic for instruments,

but boy, you can’t be doing it with the voice. I must confess, I must

belong to the Sam Barber School of Choral Writing, or the Aaron Copland.

I like hearing the text, so I like a simpler texture, basically. There

is something very different about it because the text dictates the form,

that that makes it different

BD: Does that

help or hinder when you’re selecting text?

JH: I think

it helps, actually, although there have been a couple of occasions where

I’ve had to write the text. That was a little scary because I’ve had

a couple of commissions that were really specific. I had this one

commission where the couple wanted a piece that would honor — let me see

if I remember this correctly — the winter solstice, Christmas, Kwanzaa,

and Hanukkah. But finding a text that fits that kind of requirement?

So I figured maybe I better write something. So I wrote kind of a

spiritual text that kind of encompasses all of those things. It had

to be a general sort of thing. Occasionally I’ll get ideas for words

along with the music, though. A lot of times it’ll happen when I’m

writing an individual song, but I’ll tackle anything; I really will.

I’ll try it out. Last year I did something with Latin in it.

That was an interesting exercise in trying to figure out how to set things

syllabically.

BD: Does anyone

speak Latin anymore?

JH: No, but

there are a lot of sacred pieces that use Latin. So I had to go back

and look at how other composers do it, to try to figure it out and make sure

I was doing it correctly, putting it in the right place in the line.

It’s really tricky, but it’s worth trying. It came out all right, so

I can’t complain, thank goodness!

BD: When your

score is presented to an orchestra or a soloist, is it pretty clear so they

can work with it, or is it littered with lots of little directions?

JH: No, mine’s

pretty clear. I always try to imagine what it would be like if I were

at one end of the country and someone else was doing it at the other end,

and I couldn’t get to the premiere or I couldn’t coach it. That happens

on a fairly regular basis with me, so I try to make sure that everything

is there that they need, as if I weren’t going to be there. I probably

got that from George Crumb. He used to talk about that all the time,

notating very carefully so that you are conveying as much as you can.

Also, its good for the performers, because when they go in to practice these

things, they are very shy about calling the composers and saying, “What did

you mean by this?” So I try to give them as much information as I can

without overloading them, but enough that they can find their way and try

to answer their questions. I try to anticipate what it is they might

need.

BD: Is the internet

maybe throwing another joker into this because it might be a little easier

to email you, rather than pick up the phone and call you?

JH: They’re

shy; they won’t do it. It’s amazing. I often send notes with

pieces. I have said, “Now let me know if something doesn’t work, if

it feels awkward, if you have a question,” and I don’t hear from people.

Then if I go to wherever it is being done, I’ll say, “So how’s it going?”

and they’re like, “Well, I wanted to ask you about this one thing.”

“Why didn’t you ask me before?” because they are trying to practice something

that’s awkward. People are really shy.

BD: I assume,

though, that it does please you that a lot of people are taking up your music.

JH: Oh, yes!

I can’t tell you how thrilled I am. Actually I’m kind of amazed because

the music is hard. It’s impossible to take up my music without having

some serious commitment that you’re gong to have to work on it, because

there’s like no getting around that.

BD: Would it

surprise you if you heard it in the elevator of this hotel?

JH: It would.

That has happened to me before! [Laughs] I almost wrecked the

car in Atlanta when Blue Cathedral

came on the radio. I just had the radio on, and suddenly it was like,

my gosh, that’s my piece! It’s happened every once in a while and it

always surprises me. I usually run into the furniture or walls when

it’s happening, I get so distracted. It’s totally funny. That’s pretty

amazing, though. It’s a pretty privileged place to be, because there

are so many composers out there, and they’re good. They just haven’t

had the same kind of breaks I’ve had. Some of it has been just literally

being at the right place at the right time. That’s definitely part of

it.

* *

* * *

BD: You’re doing

some teaching at Curtis. Is this composition, or flute, or what?

JH: Just composition.

It’s not a lot. We have a pretty small studio there. I’ve got

three students so it’s a pretty miniscule amount.

BD: What kind

of general advice do you have for those, or other students?

JH: Every one of those students is different.

Composition is such a difficult thing to teach. It’s not like when

I was taking flute lessons and we are all taking the Prokofiev Sonata. There are just certain

ways to do things, to articulate, to observe the dynamics or marks.

But trying to get a student out of themselves from nothing is so difficult,

which means everyone has different creative blocks.

JH: Every one of those students is different.

Composition is such a difficult thing to teach. It’s not like when

I was taking flute lessons and we are all taking the Prokofiev Sonata. There are just certain

ways to do things, to articulate, to observe the dynamics or marks.

But trying to get a student out of themselves from nothing is so difficult,

which means everyone has different creative blocks.

BD: The Prokofiev

Flute Sonata you know is there.

In their own music, you don’t know whether it’s there.

JH: Is

the student thinking of all the possibilities of what they’ve started with?

It’s a game of detective work. Each student is different. Everyone

needs something different, but I try to give them as many different ways

of looking at something as I can, because that’s the problem they’re going

to have when they leave any kind of teaching studio. They need to know

how to solve their own problems. I vary it. If they’re the kind

of student who writes a lot of music real fast, I’ll try to get them to

slow down. I try to get them to try the opposite of what they are

used to, just so they can see what it feels like.

BD: [With a

slight nudge] You’d be a great one to say slow down, don’t do so much.

[Laughs]

JH: I know!

Just don’t pay attention to what I’m doing! It’s true, Bruce; you’re

absolutely right. Sometimes they look at me and think, “Who

are you to talk?”

BD: “You’re

trying to squash my creativity!”

JH: That’s it

exactly. It’s kind of funny.

BD: What advice

do you have for audiences who hear your music — just

come?

JH: Yes.

That’s it, exactly. You don’t need to have any preconceived idea about

my music. You don’t have to know a thing about classical music.

Just come and hear it; I think you’ll enjoy it. This I say after watching

audience reactions for years now. I’m starting to realize that the

music actually works, and you don’t have to know anything about classical

music. I’ve had an awful lot of people who’ve written me letters and

emails after concerts. This is really sweet. I get emails all

the time from people who are saying things like, “I only like Bach, but I

like your music.” That’s just like an incredible compliment if you

can speak to someone like that. Wow!

BD: That means

you’ve touched them in some way.

JH: Yes, which

is just the ultimate compliment. It really is. Sometimes people

come from the audience who can’t speak because they are teary. I’m

often amazed by that, too. That’s an amazing thing to have in a lifetime,

to be able to do some sort of art form that moves people.

BD: Is that

scary to know that some of these little dots and squiggles you put down

are really going to touch people?

JH: Yes, it

is scary, actually. Sometimes it’s kind of an awesome responsibility.

I’m aware of it. It’s true, but I’m always aware that I have a certain

responsibility in creating an art form. Because I have the opportunities,

I know that I need to make the most of them. I’m constantly going

through other composers works and trying to find things that I might be

able to pass along to somebody. I’m always doing that, and I find

it fascinating to hear what other people are doing. That’s the other

thing I love.

BD: You’re trying

to keep up.

JH: I’m always

in Tower Records buying things, and people send me CDs all the time.

So I’m always listening to those and seeing what people are doing.

Sometimes I’ll get calls from orchestras asking, “Do you know anything from

a young composer that’s seven minutes, that’s kind of fast?”

Because I judge competitions and things, I run across things. You

go through several hundred scores and recordings, and occasionally you’ll

run across a real gem. So usually I’ll contact the composer to see

if I can get a copy. Also, the kids at Curtis are having to apply

for competitions and things, and sometimes there are requirements; they’ll

need a violin piece that’s from 1995. So they’re looking for things

specifically, and sometimes I’m aware of a piece that I can pass on.

BD: Put it on

a page your website.

JH: That’s a

good idea. That’s a really good idea. I hadn’t thought about that.

[Laughs] I’ll have to talk to my website guy. That’s great, Bruce.

That’s actually a really good idea. I don’t maintain my website because

I just can’t. I don’t have enough time to do it, but I have a flute

friend who does, and it’s good having him. I’m amazed how any people

access that website to find information! It’s invaluable. Those

things are just invaluable! It’s incredible. It has changed music,

really, because now you don’t have to be with a publisher. You can

do it yourself because people can find you. That used to be one of

the battles, so I think it’s altering it a lot. It really is.

BD: Hopefully

for the better...

JH: Yes.

Well, I guess we won’t know for a while, will we? We must have another

conversation in ten years. Think about the decade between 1994 and

2004, the changes have been extraordinary. So what will it be

in 2014? [Purely coincidentally,

it is now 2014 when this conversation is being posted on my website.]

BD: I’ll meet

you back here then.

JH: That sounds

good.

BD: Just for

my records, may I ask your birth date?

JH: Yes...

New Year’s Eve, 1962. December 31st is kind of an odd time to have

a birthday. It means I’m always a year older. I look a year older

than I actually am because everyone always calculates by the year you were

born, ’62, so I just turned forty-one. But it’s kind of an interesting

time to have a birthday then. I don’t forget it.

BD: Plus it

gives you an extra tax deduction that year.

JH: That’s right.

That’s what my parents always tell me, “You were a tax deduction.”

[Both laugh] So I tell them, “Thanks, Mom and Dad. I’m glad I

could help out.”

BD: One last

question. Is composing fun?

JH: It’s both

fun and agonizing. Parts of it are joyous and parts of it are just agony!

It’s amazing how hard it is, and I don’t think it gets any easier.

It’s hard; you’re always worrying. You think this isn’t going to work!

This isn’t going to work! And sometimes I think it’s not going to

work right up to the performance. It’s amazing how often that happens.

I was really encouraged when I read something recently. John Adams

said that every time he hears a piece of his for the first time, he is always

horrified. Wow, that’s encouraging! I always considered John

Adams to be a real pro at handling things, but to hear him say that made

me feel a whole lot better.

BD: I would

think you would be relieved when your own piece worked!

JH: I am, but

my music is hard enough that I sometimes have a little bit of anxiety of what

I’m putting people through. I also know that my perspective of hearing

is not going to be what the rest of the audience is experiencing. I

know the spots that I’m worried about, and I swear I have some sort of reaction

when they are going through the music. I’m like, “Will this work?

Will this work?” and I’m sometimes really caught off guard by whether it

works or not. I’ll ask musicians, “Do you think this works? Does

it feel all right?” Sometimes it is a pleasant surprise though; it

really is. It’s a hard job, but I can’t live without it, so I’m not

exactly sure how to answer the question. I need it; I really need it.

I have no choice, but boy, sometimes it‘s real agony.

BD: As my old

teacher Tom Willis,

the Music Critic for the Chicago Tribune

used to say, we all work to support our habit.

JH: Isn’t that

the truth? It really is.

BD: I’ve got

some recordings of some of your compositions and also your flute playing.

Are there some recordings of your conducting?

JH: Actually

only on someone else’s recording. Robert Maggio, a composer from Philadelphia,

has a piece that came out on CRI. Probably if you typed me in on a

place like Amazon, I think it does pull me up as a conductor. But I’ve

actually curtailed my conducting stuff because Spano made me realize that

if you are going to get up on the podium, you have a real responsibility

to know what you are doing. It’s almost impossible to learn the scores

like you really should know them and still maintain the amount of composing

I’m doing. But I’m sure at some point I’ll probably get back to it.

I’m sure I will.

BD: Will you

keep up the flute playing?

JH: Yes, that’s

a little more consistent. I am also running my own publishing company.

It’s a lot of work. I’m still trying figure out how to balance that

with so many performances going on in a year.

BD: Do you get

enough time to compose?

JH: Yes, although

this year I am struggling a little more than I normally do. I carry

a laptop around so I can work in hotel rooms! I worked on the plane

all the way down here from Philly to Chicago. I actually spent the

whole time composing ‘til they told me I had to turn the computer off.

I’m trying to clear out a little more time so I’m not so squashed.

It’s maybe more healthy creatively.

BD: Maybe sometime

you’ll just have to take a few months off. Build it into your schedule.

JH: Yes, I think

that’s what I’m going to have to do. I think you’re absolutely right.

BD: Go sit

on a beach for a month.

JH: Oh that

sounds good. [Both laugh] That’s funny... I was dreaming about

Hawaii today. I was thinking I bet it’s 80 degrees there! What

are we doing on the mainland? [Note:

This interview took place in mid-February, so it was very cold in both Philadelphia

and Chicago.] [Both continue to laugh]

BD: Adjust your

commissions!

JH: I know.

Folks, I’ve got to do this in Hawaii! Oooh, that sounds good.

It does. Then I can go to the Caribbean............. [More laughter

as we said our good-byes.]

=======

======= =======

======= =======

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

--

======= =======

======= =======

=======

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel in Chicago on February

14, 2004. Portions were broadcast on WNUR later that year. This

transcription was made and posted on this website in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he

now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

JH: Actually, probably both. That’s a good

question. It’s funny; the whole idea behind this Band Quest series

is that they’re trying to get established composers — people

like Chen Yi and Michael

Daugherty — who normally writes orchestra music to try writing something

for band, but something that will communicate to a much younger group.

It is really amazing how difficult it is because you write something, you

look at it, and you wonder if it is going to work, or if they can play it.

To me it looks simple, but I realize with all the training that we go through,

it’s a different prospect for a junior high group! [Laughs]

Oh, boy, is it!

JH: Actually, probably both. That’s a good

question. It’s funny; the whole idea behind this Band Quest series

is that they’re trying to get established composers — people

like Chen Yi and Michael

Daugherty — who normally writes orchestra music to try writing something

for band, but something that will communicate to a much younger group.

It is really amazing how difficult it is because you write something, you

look at it, and you wonder if it is going to work, or if they can play it.

To me it looks simple, but I realize with all the training that we go through,

it’s a different prospect for a junior high group! [Laughs]

Oh, boy, is it! JH: Actually I have done that before, especially

with tempos. It’s interesting with tempos; it really changes from

ensemble to ensemble and from hall to hall. I’m amazed at how much

it changes. When I play my own pieces, I change the tempos, too, so

I don’t hold anyone to them strictly! [Laughs] I tell musicians

that, because they always ask. They ask if I mind, and I say, “Oh,

no. I’m changing my tempos all the time.”

JH: Actually I have done that before, especially

with tempos. It’s interesting with tempos; it really changes from

ensemble to ensemble and from hall to hall. I’m amazed at how much

it changes. When I play my own pieces, I change the tempos, too, so

I don’t hold anyone to them strictly! [Laughs] I tell musicians

that, because they always ask. They ask if I mind, and I say, “Oh,

no. I’m changing my tempos all the time.” BD: What is it that makes a piece of music

— either your music or other music — worthwhile?

BD: What is it that makes a piece of music

— either your music or other music — worthwhile? BD: With all of these commissions, are there still

some pieces that you just want to write and have to get out of your system?

BD: With all of these commissions, are there still

some pieces that you just want to write and have to get out of your system? JH: Every one of those students is different.

Composition is such a difficult thing to teach. It’s not like when

I was taking flute lessons and we are all taking the Prokofiev Sonata. There are just certain

ways to do things, to articulate, to observe the dynamics or marks.

But trying to get a student out of themselves from nothing is so difficult,

which means everyone has different creative blocks.

JH: Every one of those students is different.

Composition is such a difficult thing to teach. It’s not like when

I was taking flute lessons and we are all taking the Prokofiev Sonata. There are just certain

ways to do things, to articulate, to observe the dynamics or marks.

But trying to get a student out of themselves from nothing is so difficult,

which means everyone has different creative blocks.