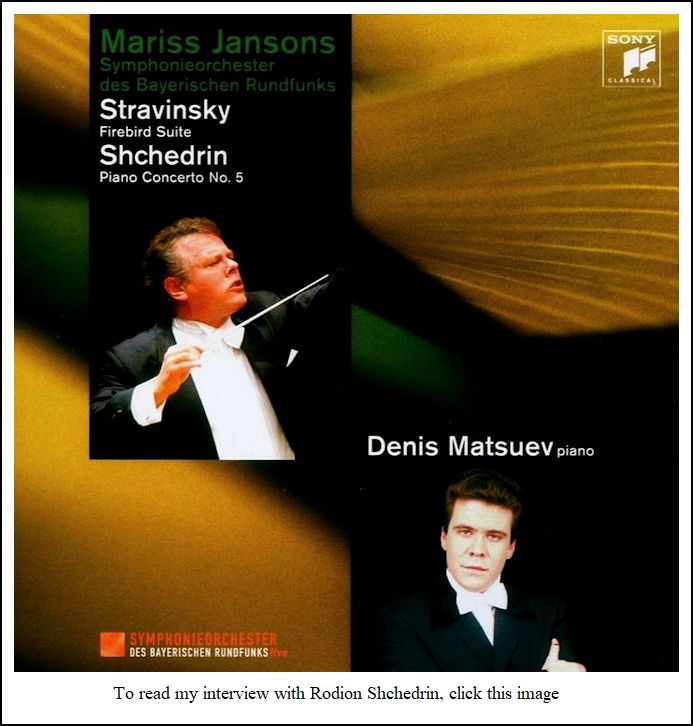

| Born January 14, 1943 in the Latvian

capital of Riga, Mariss Jansons grew up in the Soviet Union as the son

of conductor Arvid Jansons, studying violin, viola and piano and completing

his musical education in conducting with high honors at the Leningrad

Conservatory. Further studies followed with Hans Swarowsky in Vienna

and Herbert von Karajan in Salzburg. In 1971 he won the conducting competition

sponsored by the Karajan Foundation in Berlin. His work was also significantly

influenced by the legendary Russian conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky, who

engaged Jansons as his assistant at the Leningrad Philharmonic in 1972.

Over the succeeding years, Jansons remained loyal to this orchestra, today

re-named the St. Petersburg Philharmonic, as a regular conductor until

1999, conducting the orchestra during that period on tours throughout

the world. From 1971 to 2000 he was also professor of conducting at the

St. Petersburg Conservatoire. In 1979 he was appointed Music Director of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, with which ensemble he performed, recorded and toured extensively. It was in 1996, whilst in Oslo, that Jansons had a serious heart attack whilst on the podium. He was subsequently fitted with a defibrillator. (Earlier, Jansons's father had died while conducting the Halle Orchestra in Manchester). Jansons remained with the Oslo orchestra until 2000. In 1992, he became principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and in March, 1997, he was appointed music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Since 2003 Jansons has been Chief Conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. After two exceptionally successful seasons his contract was extended in June of 2005 for three additional years until 2009. Jansons follows Eugen Jochum, Rafael Kubelík, Sir Colin Davis and Lorin Maazel as the fifth Chief Conductor of these two renowned Bavarian Broadcasting ensembles. In 2004 Jansons assumed the position of Chief Conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. Jansons places special emphasis on his work with young musicians. He has conducted the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra on a European tour and worked with the Attersee Institute Orchestra, with which he appeared at the Salzburg Festival. In Munich he gives regular concerts with various Bavarian Youth Orchestras and the Academy of the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks. He is also Artistic Director of the Masterprize Composing Competition. Jansons’s discography includes many recordings for EMI, some of which have received prestigious international prizes. The recording of Shostakovich’s Symphony No.7 with the Leningrad Philharmonic won the 1989 Edison Prize and his recordings of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Dvorák’s Fifth Symphony were awarded, respectively, the Dutch Luister Prize and the Penguin Award. In 2005 Jansons concluded recording his cycle of all the Shostakovich Symphonies, an EMI project in which a number of major orchestras participated. On January 1, 2006, Jansons was, for the first time, conductor at the annual New Year’s Concert of the Vienna Philharmonic, which was telecast by 60 different stations on every continent, and seen by more than fifty million viewers.

-- Biography from Warner Classics [Text

only; photo from the Bavarian Radio Orchestra webpage]

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

MJ: Symphonic music, no, unfortunately it is not.

It would be nice if symphonic music could be for everybody. It

must be for everybody, but not all people know what symphonic music is

because now, especially now in our times in the twentieth-century, we

have many concerts, and sometimes the public relations for symphonic music

is not enough. So, it means we always have a special group of people

who know this symphonic music, and understand and follow, and our responsibility

as musicians is finding out how to build a new generation to understand

and like this music. I know so many people who would like to hear

and understand symphonic music, but they are afraid. They think

it’s something so difficult, and when they are afraid, they don’t listen

to this music. They follow the way which is much easier, to listen

to pop music and light music. But everybody must know many kinds

of music, and they must try to listen to decide perhaps it’s very nice.

This is especially important for young people. The real problem now

is that we don’t have enough propaganda.

MJ: Symphonic music, no, unfortunately it is not.

It would be nice if symphonic music could be for everybody. It

must be for everybody, but not all people know what symphonic music is

because now, especially now in our times in the twentieth-century, we

have many concerts, and sometimes the public relations for symphonic music

is not enough. So, it means we always have a special group of people

who know this symphonic music, and understand and follow, and our responsibility

as musicians is finding out how to build a new generation to understand

and like this music. I know so many people who would like to hear

and understand symphonic music, but they are afraid. They think

it’s something so difficult, and when they are afraid, they don’t listen

to this music. They follow the way which is much easier, to listen

to pop music and light music. But everybody must know many kinds

of music, and they must try to listen to decide perhaps it’s very nice.

This is especially important for young people. The real problem now

is that we don’t have enough propaganda.|

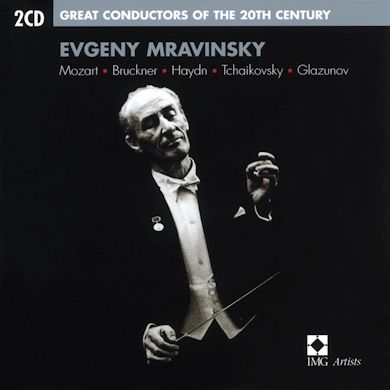

The eminent Russian conductor, Yevgeny [Evgeny] Aleksandrovich

Mravinsky (Russian: Евге́ний Алекса́ндрович Мрави́нский), was born in Saint

Petersburg on June 4, 1903. The soprano Yevgeniya Mravina was his aunt.

His father, Alexandr Konstantinovich Mravinsky, died in 1918, and in that

same year, Yevgeny began to work backstage at the Mariinsky Theatre. He

first studied biology at the university in Leningrad, before going to the

Leningrad Conservatory in 1924 to study music (conducting with Aleksandr

Gauk and Nikolai Malko), graduating in 1931. He also had courses in composition

with Scherbachev.

Mravinsky served as a pantomimist and rehearsal pianist (repetiteur)

at the Imperial Ballet from 1923 to 1931. His first public conducting appearance

was in 1929. He was conductor of of the Leningrad Theater of Opera and Ballet

from 1932 to 1938 (Kirov Ballet and Bolshoi Opera). In September 1938,

he won the All-Union Conductors Competition in Moscow.

Mravinsky served as a pantomimist and rehearsal pianist (repetiteur)

at the Imperial Ballet from 1923 to 1931. His first public conducting appearance

was in 1929. He was conductor of of the Leningrad Theater of Opera and Ballet

from 1932 to 1938 (Kirov Ballet and Bolshoi Opera). In September 1938,

he won the All-Union Conductors Competition in Moscow.In October 1938, Mravinsky took up the post that he was to hold for 50 years, until 1988: Principal Conductor of the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, with whom he had made his debut as a conductor in 1931. Under Mravinsky, the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra gained a legendary reputation, particularly in Russian music such as Tchaikovsky and Dmitri Shostakovich. During World War II, Mravinsky and the orchestra were evacuated to Siberia. He gave world premieres of six symphonies by Shostakovich: Nos. 5, 6, 8 (which is dedicated to Mravinsky), 9, 10 and finally 12 in 1961. His refusal to conduct the premiere of Symphony No. 13 in 1962 caused a permanent rupture in their friendship. He premiered Sergei Prokofiev's Symphony No. 6 in Leningrad the year of its composition (1947). He also conducted works by Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky. Mravinsky made commercial studio recordings from 1938 to 1961. His issued recordings from after 1961 were taken from live concerts. He first went on tour abroad in 1946, including performances in Finland and in Czechoslovakia (at the Prague Spring Festival). Later tours with orchestra included a June 1956 itinerary to West Germany, East Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Their only tour to Great Britain was in September 1960 to the Edinburgh Festival and the Royal Festival Hall, London. Their first tour to Japan was in May 1973. Their last foreign tour was in 1984, to West Germany. His last concert was on March 6, 1987. In 1973, he was awarded the Order of Hero of Socialist Labor. Mravinsky died in Leningrad on January 19, 1988, aged 84. He represented the best of the Soviet school of conducting, in which technical precision and fidelity to the music were combined with individual and even Romantic interpretations. He was especially noted for his fine performances of Tchaikovsky’s operas, ballets, and symphonies. Recordings reveal Mravinsky to have an extraordinary technical control over the orchestra, especially over dynamics. He was also a very exciting conductor, frequently changing tempo in order to heighten the musical effect for which he was striving, often making prominent use of brass instrumentation. Surviving videos show that Mravinsky had a sober appearance at the podium, making simple but very clear gestures, often without a baton. |

MJ: Oh, yes, of course. We must play contemporary

music. For example, in Leningrad we must play the works of Leningrad

composers. Otherwise, they write the music and couldn’t get it

played. If we in Leningrad will not play this music, who will

play it? But if it’s a very good piece, later everybody can play

this work. It started the same with great composers. I remember,

when I was a small child in the ’50s, not everybody

understood Shostakovich. Now it’s not a problem, but seventy years

ago, not all people in the public understood Shostakovich.

MJ: Oh, yes, of course. We must play contemporary

music. For example, in Leningrad we must play the works of Leningrad

composers. Otherwise, they write the music and couldn’t get it

played. If we in Leningrad will not play this music, who will

play it? But if it’s a very good piece, later everybody can play

this work. It started the same with great composers. I remember,

when I was a small child in the ’50s, not everybody

understood Shostakovich. Now it’s not a problem, but seventy years

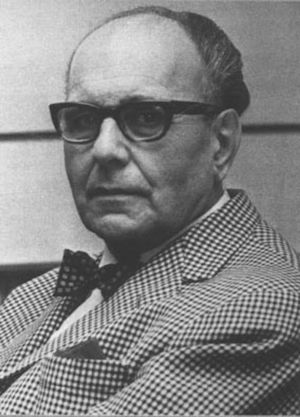

ago, not all people in the public understood Shostakovich.  Hans Swarowsky (September 16, 1899 in Budapest - September 10, 1975 in

Vienna) was celebrated as both a conductor and as a teacher. He studied composition

in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern and conducting with Richard

Strauss, Felix Weingartner and Clemens Krauss.

Hans Swarowsky (September 16, 1899 in Budapest - September 10, 1975 in

Vienna) was celebrated as both a conductor and as a teacher. He studied composition

in Vienna with Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern and conducting with Richard

Strauss, Felix Weingartner and Clemens Krauss.He held positions in Stuttgart, Gera, Hamburg (1932), Berlin (1934), Zürich (1937-1940), Krakow (1944-1946), Graz (1947-1950) and at the Vienna State Opera (1957). He was chief conductor of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, from 1957 to 1959. From 1959 he was chief conductor of Vienna Symphony Orchestra, and appeared also as guest conductor of the Vienna State Opera. Perhaps Swarowsky's fame rests most with his reputation as a teacher. For many years Professor Swarowsky held master classes in conducting at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, where he was head of conducting from 1946. Famous students of Swarowsky's include Claudio Abbado, Albert Rosen, Jesús López-Cobos, Bruno Weil, Mariss Jansons, Giuseppe Sinopoli and Zubin Mehta. Many aspiring young conductors compete in the Hans Swarowsky International Conductors Competition, held in Vienna. Swarowsky's lectures and essays were collected into the publication Wahrung der Gestalt (Keeping Shape), which today serves as an encyclopaedia for performance and conducting. Swarowsky made many recordings with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and the Vienna State Opera Orchestra. His recordings appear on the Supraphon, Concert Hall, Nonesuch, Erato, Preiser, Vox and Vanguard labels. He also recorded a complete Der Ring des Nibelungen with the Prague National Theatre Orchestra. |

MJ: Yes. I have had very good relationships with

many soloists. I like very much accompaniment, and I give attention

to accompaniment. I always try to give, if possible, more time

to rehearse accompaniments. I never play concertos with just one

rehearsal. I’ll always have at least two rehearsals for accompaniment.

It’s the same, even if it’s a very, very popular concerto, like Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto, or Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto. I always

would like to have two rehearsals because I think it’s necessary.

It’s not that we need the extra time. I know the piece very well;

the orchestra knows it; the soloist, of course, but it’s the ensemble playing,

the preparation. You need time so that in the evening you can be very

free and follow the soloist. You know very well how his pulse is

going, and you can only know it when you rehearse with him. I like

very much when we have enough time for accompaniment.

MJ: Yes. I have had very good relationships with

many soloists. I like very much accompaniment, and I give attention

to accompaniment. I always try to give, if possible, more time

to rehearse accompaniments. I never play concertos with just one

rehearsal. I’ll always have at least two rehearsals for accompaniment.

It’s the same, even if it’s a very, very popular concerto, like Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto, or Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto. I always

would like to have two rehearsals because I think it’s necessary.

It’s not that we need the extra time. I know the piece very well;

the orchestra knows it; the soloist, of course, but it’s the ensemble playing,

the preparation. You need time so that in the evening you can be very

free and follow the soloist. You know very well how his pulse is

going, and you can only know it when you rehearse with him. I like

very much when we have enough time for accompaniment.

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 2, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in March and November of 1990, and again in January of 1993. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.