Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879 – August 2, 1955) was an American modernist poet. He was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, educated at Harvard and then New York Law School, and he spent most of his life working as an executive for an insurance company in Hartford, Connecticut. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his Collected Poems in 1955. Stevens studied the art of poetic expression in many of his writings and poems including The Necessary Angel where he stated, "The imagination loses vitality as it ceases to adhere to what is real. When it adheres to the unreal and intensifies what is unreal, while its first effect may be extraordinary, that effect is the maximum effect that it will ever have." |

Jencks: It’s too complicated to say. It’s obviously

both. Different pieces are different. It depends what forced

you to do it. Some things are so powerful that you have hardly

any control. They come because they have to. You don’t have

any control, and you don’t have anything to do about the scene that you’re

in control of. It’s like when you give a concert. You’ve had

experiences in your life, and they’re strong

enough so it forces you to play a certain piece. Then when you’re

playing it, some of that memory may be on your mind. The tremendous

control comes because you had to work it, playing it 3,000 times before

you play it in public. That’s called control, but it isn’t because

it’s the slow emerging. There’s a wonderful

book on mathematics by Jacque Hadamard. It’s

called The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field.

It’s the description of how about a couple hundred European mathematicians

were interviewed, and where their ideas came from. This very problem

is stated quite clearly, that whether it’s

a discovery or an invention, nobody knows. These words are very subtle,

but whether you give yourself over to the thing, or whether it takes hold

of you, you don’t have much choice. You don’t have any mathematics,

of course, but the same thing is somewhat true in composition, and it comes

on a much deeper level because it comes from your emotional life. It’s

something that happens to you. I don’t

say that some of it wasn’t your fault, but when

it happens, experiences are very quick sometimes. I remember when

the Korean War was announced on a radio, I was with some friends. This

sudden knowledge that we were back like the Second World War again, which

everybody hoped we wouldn’t be, and there we were. That hits you

like a knife going through you. Any experience you have for the next

five years in regard to that war is subservient to that moment.

You can’t help that, and that’s the kind of thing

that produces a few notes, or a piece, or something. I’m

not interested in the music all by itself. It has to come from

something that is powerful enough to produce something, as far as I’m

concerned.

Jencks: It’s too complicated to say. It’s obviously

both. Different pieces are different. It depends what forced

you to do it. Some things are so powerful that you have hardly

any control. They come because they have to. You don’t have

any control, and you don’t have anything to do about the scene that you’re

in control of. It’s like when you give a concert. You’ve had

experiences in your life, and they’re strong

enough so it forces you to play a certain piece. Then when you’re

playing it, some of that memory may be on your mind. The tremendous

control comes because you had to work it, playing it 3,000 times before

you play it in public. That’s called control, but it isn’t because

it’s the slow emerging. There’s a wonderful

book on mathematics by Jacque Hadamard. It’s

called The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field.

It’s the description of how about a couple hundred European mathematicians

were interviewed, and where their ideas came from. This very problem

is stated quite clearly, that whether it’s

a discovery or an invention, nobody knows. These words are very subtle,

but whether you give yourself over to the thing, or whether it takes hold

of you, you don’t have much choice. You don’t have any mathematics,

of course, but the same thing is somewhat true in composition, and it comes

on a much deeper level because it comes from your emotional life. It’s

something that happens to you. I don’t

say that some of it wasn’t your fault, but when

it happens, experiences are very quick sometimes. I remember when

the Korean War was announced on a radio, I was with some friends. This

sudden knowledge that we were back like the Second World War again, which

everybody hoped we wouldn’t be, and there we were. That hits you

like a knife going through you. Any experience you have for the next

five years in regard to that war is subservient to that moment.

You can’t help that, and that’s the kind of thing

that produces a few notes, or a piece, or something. I’m

not interested in the music all by itself. It has to come from

something that is powerful enough to produce something, as far as I’m

concerned. Jencks: No. That is not what

I’m interested in. That’s probably pretty peculiar, but I just don’t

think in those terms. The fact is it always irritates me when

I read The New York Times, and it says ‘arts

and entertainment’. That’s crazy. I’ve

been reading Shaw recently. His whole attitude towards art is

very interesting. I don’t have to agree

with it. It’s certainly far away from that.

Oh, it’s entertaining, but that’s

different. It’s not ‘entertainment’.

There’s nobody more entertaining than Shaw, but he’s got something

to say. I don’t agree with what he has

to say about dictatorships. I’m not a great admirer of Stalin,

or Mussolini, or even Hitler, and Shaw liked dictatorships. But

aside from that little detail, he knows what he’s talking about. He

has something that he wants to say, and he says it very entertainingly,

which I’m afraid my music doesn’t go with.

Jencks: No. That is not what

I’m interested in. That’s probably pretty peculiar, but I just don’t

think in those terms. The fact is it always irritates me when

I read The New York Times, and it says ‘arts

and entertainment’. That’s crazy. I’ve

been reading Shaw recently. His whole attitude towards art is

very interesting. I don’t have to agree

with it. It’s certainly far away from that.

Oh, it’s entertaining, but that’s

different. It’s not ‘entertainment’.

There’s nobody more entertaining than Shaw, but he’s got something

to say. I don’t agree with what he has

to say about dictatorships. I’m not a great admirer of Stalin,

or Mussolini, or even Hitler, and Shaw liked dictatorships. But

aside from that little detail, he knows what he’s talking about. He

has something that he wants to say, and he says it very entertainingly,

which I’m afraid my music doesn’t go with.

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.;

October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar, born

in McAlester, Oklahoma. He was a major figure in American poetry in the

second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in the Confessional

school of poetry.

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.;

October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar, born

in McAlester, Oklahoma. He was a major figure in American poetry in the

second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in the Confessional

school of poetry.Berryman's great poetic breakthrough occurred with 77 Dream Songs (1964). It won the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for poetry and solidified Berryman's standing as one of the most important poets of the post-World War II generation. Soon thereafter, the press began to give Berryman a great deal of attention, as did arts organizations and even the White House, which sent him an invitation to dine with President Lyndon B. Johnson (though Berryman declined because he was in Ireland at the time). Berryman was raised in Oklahoma until the age of ten, when his father, John Smith, a banker, and his mother, Martha (also known as Peggy), a schoolteacher, moved to Florida. In 1926, in Clearwater, Florida, when Berryman was 11 years old, his father shot and killed himself. Berryman was haunted by his father's death for the rest of his life, and wrote about his struggle to come to terms with it in much of his poetry. Berryman taught or lectured at a number of universities, including the University of Iowa (at the Writer's Workshop), Harvard University, Princeton University, the University of Cincinnati, and the University of Minnesota, where he spent most of his career, except for his sabbatical year in 1962–3, when he taught at Brown University. According to the editors of The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, he lived turbulently. He abused alcohol and struggled with depression, and on the morning of January 7, 1972, he killed himself by jumping from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis onto the west bank of the Mississippi River. |

|

Landowska was born in Warsaw to Jewish parents. Her father was a lawyer, and her mother a linguist who translated Mark Twain into Polish. She began playing piano at the age of four, and studied at the Warsaw Conservatory with the senior Jan Kleczyński and Aleksander Michałowski. She was considered a child prodigy. She studied composition and counterpoint under Heinrich Urban in Berlin, and had lessons in Paris with Moritz Moszkowski. She began her performing career in Paris, where her recitals in that city and other European cities garnered praise from critics. She was interested in the music of J. S. Bach, whose works for harpsichord were included in her recitals by 1903, earning praise from Albert Schweitzer. She decided to devote her career to the harpsichord rather than the piano, against the wishes of her friends, who thought she had a promising future as a pianist. In 1908–09, she toured Russia with a Pleyel harpsichord, similar to the 1889 model that the firm displayed at the Paris Exposition. After eloping with and marrying Polish folklorist and ethnomusicologist Henry Lew in 1900 in Paris, she taught piano at the Schola Cantorum there (1900–1912). She later taught harpsichord at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (1912–1919). When World War I started in 1914, she was interned on the grounds that she was a foreign national. She had her American debut in 1923, touring major cities with four Pleyel Grand Modele de Concert harpsichords, which were huge seven-and-a-half foot long instruments with foot pedal-controlled registers. These were large, heavily built harpsichords with a 16-foot stop (a set of strings an octave below normal pitch) and owed much to piano construction. Deeply interested in musicology, and particularly in the works of Bach, Couperin and Rameau, she toured the museums of Europe looking at original keyboard instruments; she acquired old instruments and had new ones made at her request by Pleyel and Company. Responding to criticism by fellow Bach specialist Pablo Casals, she once said: "You play Bach your way, and I'll play him 'his' way." A number of important new works were written for her: Manuel de Falla's El retablo de maese Pedro (Master Peter's Puppet Show) marked the return of the harpsichord to the modern orchestra. Falla later wrote a harpsichord concerto for her, and Francis Poulenc composed his Concert champêtre for her. She taught at the Curtis Institute of Music from 1925 until 1928. She established the École de Musique Ancienne at Paris in 1925: from 1927, her home in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt became a center for the performance and study of old music.After World War II, she settled in Lakeville, Connecticut in 1949, and re-established herself as a performer and teacher in the United States, touring extensively. Her last public performance was in 1954. Landowska recorded extensively for the Victor Talking Machine Company/RCA Victor and The Gramophone Company/EMI. |

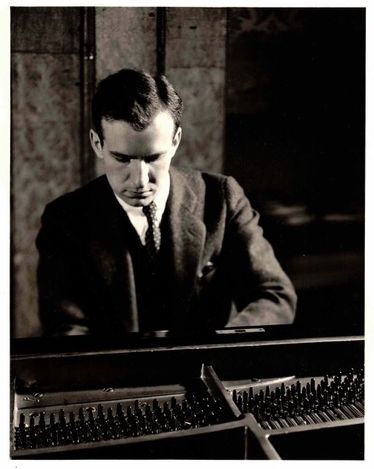

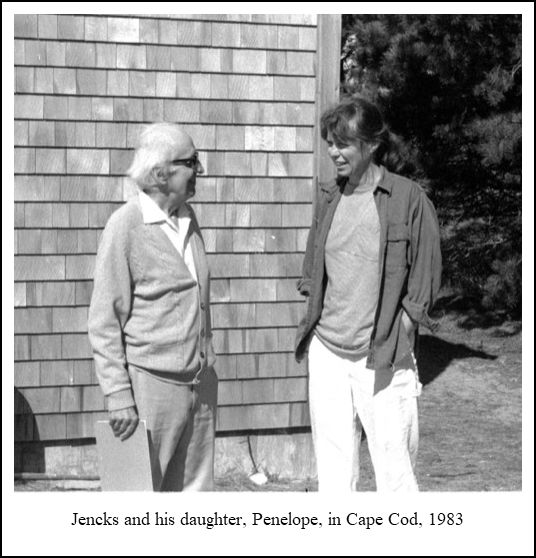

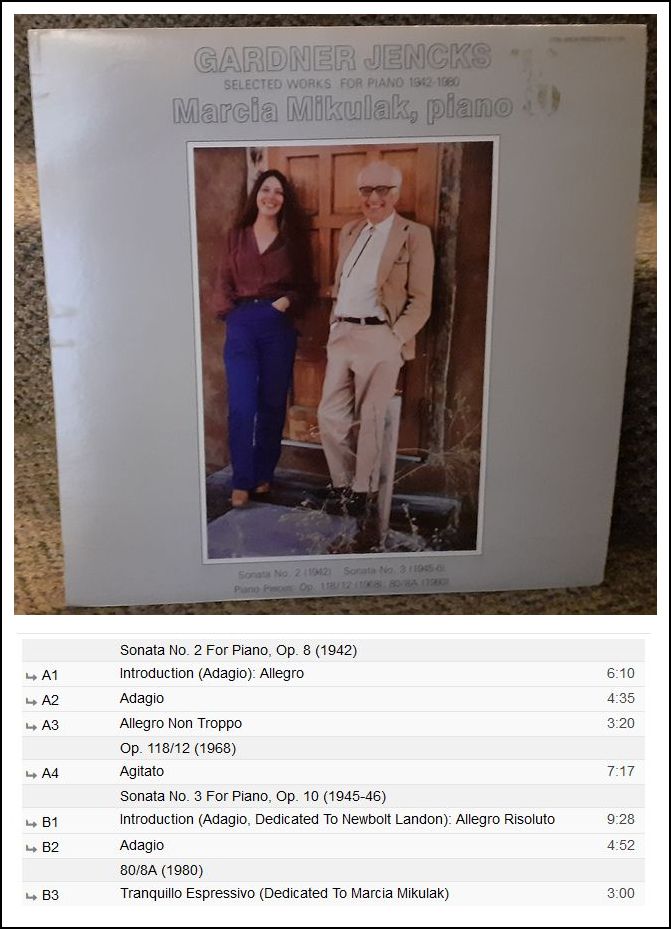

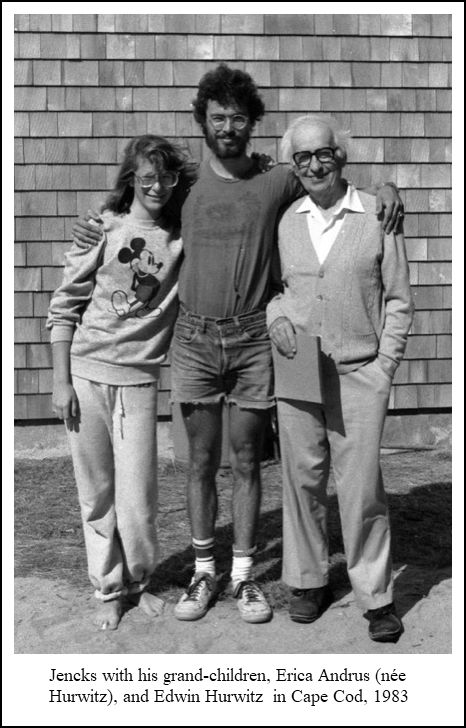

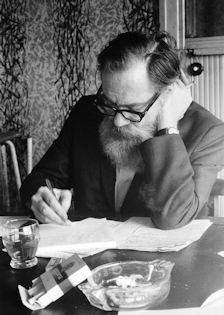

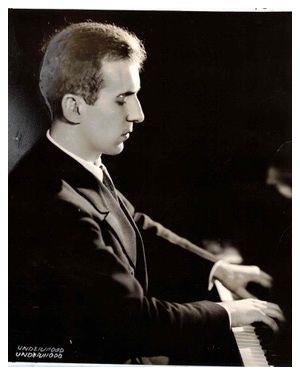

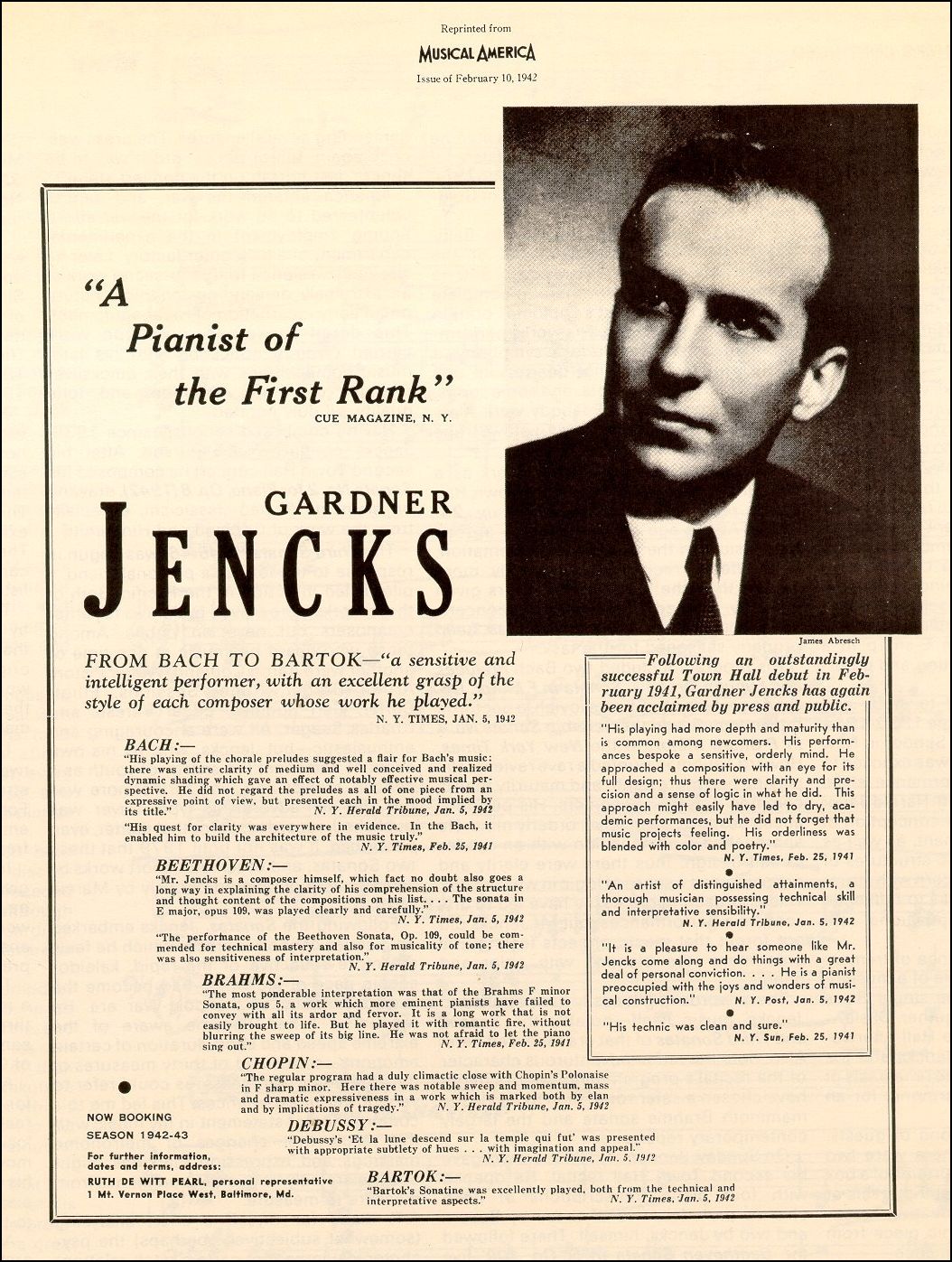

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on October 10, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1992 and 1997. This transcription

was made in 2020, and posted on this website

at that time. Family photos from the composer’s

grandson were added in 2024.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.