|

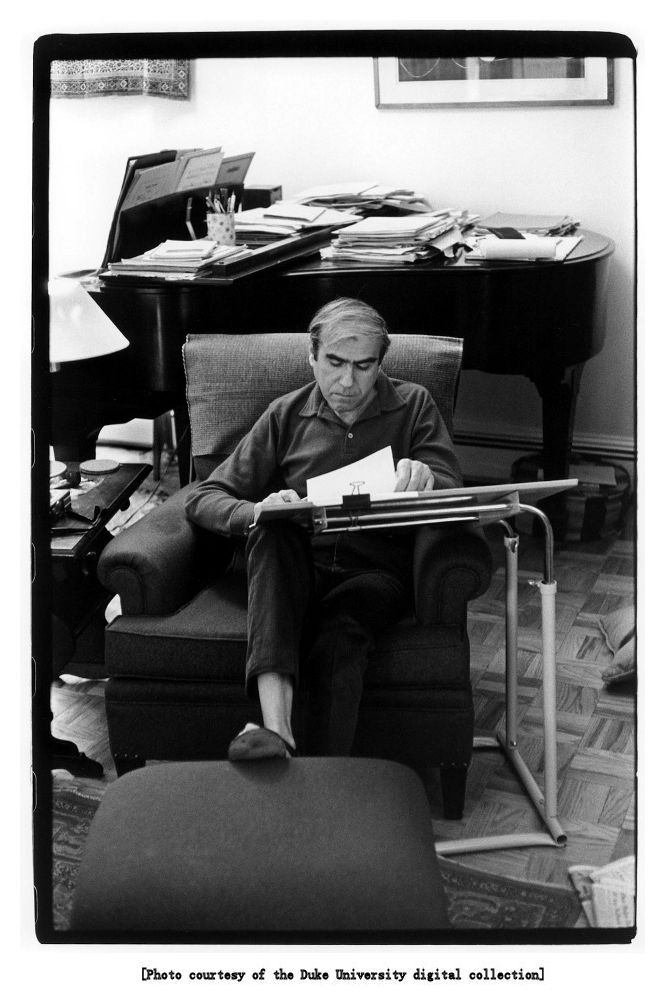

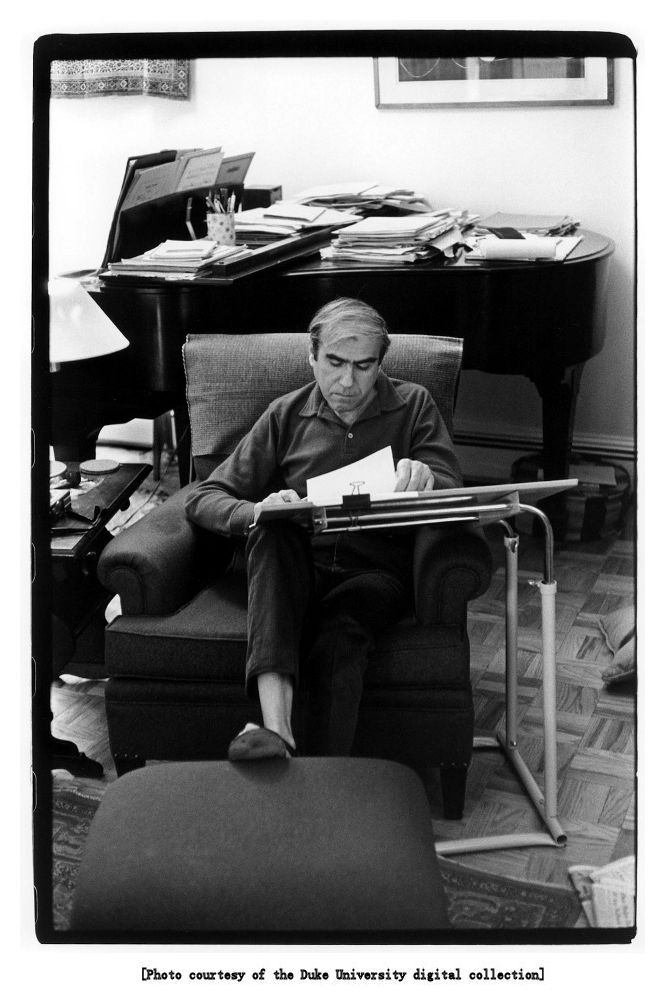

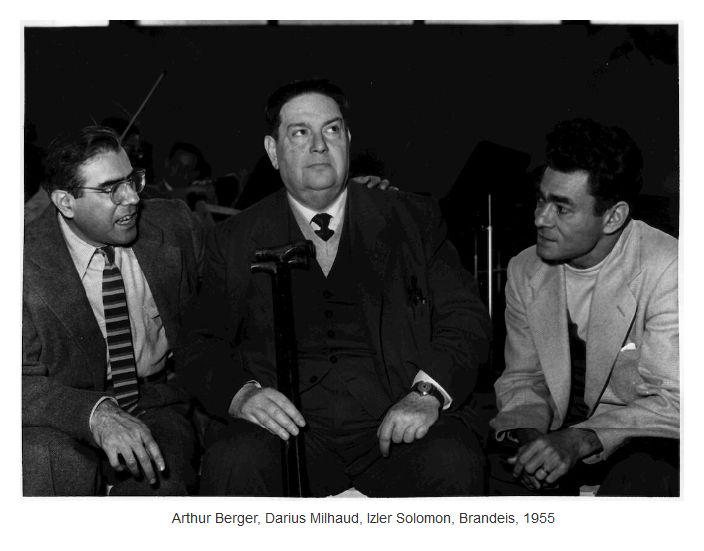

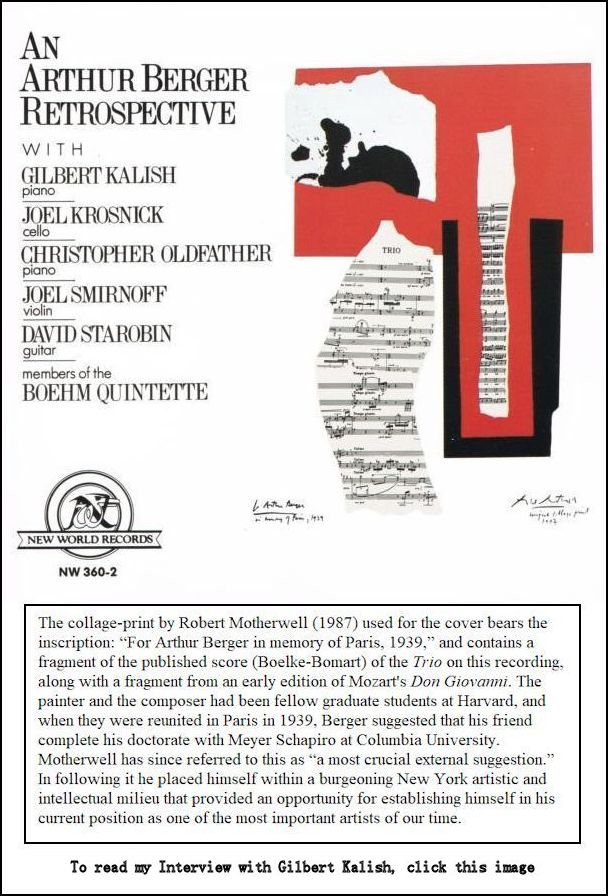

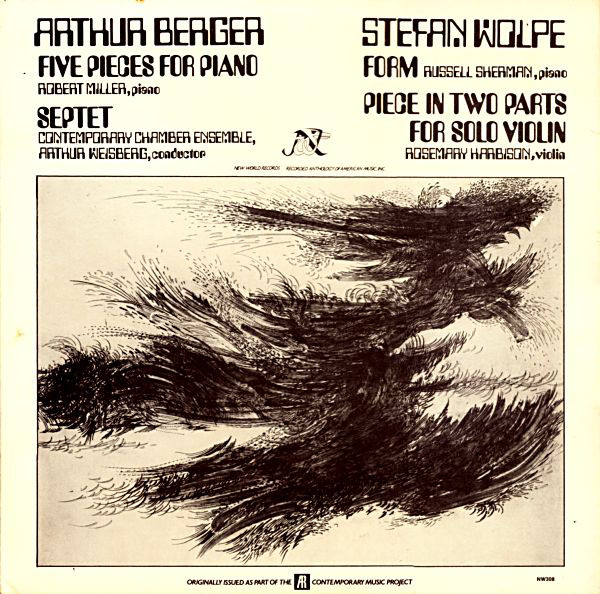

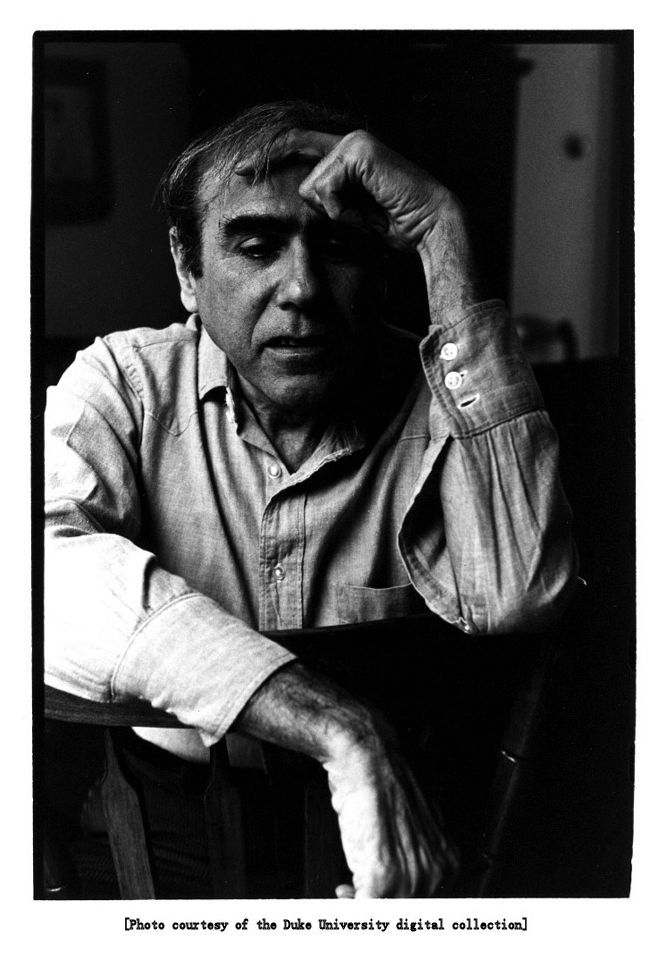

Born in 1912 in New York City, Berger received his musical education at New York and Harvard Universities, pursuing further studies in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and at the Sorbonne. In his early twenties he was a member of the Young Composers Group that revolved around Aaron Copland as its mentor. In his capacity as critic, Berger became one of the principal spokesmen of music from the United States for that period. He wrote numerous critical and analytical articles on such composers as Igor Stravinsky, Charles Ives, and Aaron Copland. Berger received a number of awards and honors, including those from the Guggenheim, Fromm, Coolidge, Naumburg and Fulbright Foundations, the NEA, League of Composers, and Massachusetts Council on the Arts & Humanities. He was a fellow of both the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Berger began his teaching career in 1939 at Mills College in Oakland, California. In 1943 he became a music critic for the New York Sun and in 1946 accepted Virgil Thomson's invitation to join the New York Herald Tribune. After a decade as a full-time music reviewer in New York City, he resumed teaching in 1953 at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts during the formation of its graduate music program. After retiring from Brandeis in 1980, Berger taught at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston until 1999. His music is recorded on the CRI and New World labels, and his book Reflections of an American Composer (2002) was recently published by the University of California Press. |

BD: How much of that is a myth?

BD: How much of that is a myth? AB: You really ask difficult questions! [Both

laugh] One develops a kind of peer group, and the recognition of your

peer group is very important to you because it’s some confirmation.

When I write, in a sense I write simply for myself. That sounds very

curious and elitist, but I want to sit there as an audience. I want

to say, “Is that something that I’m going to listen

to, and listen to many times?” and if I ask some of

my peers to verify my judgment, it helps me to think that I have achieved

my goal. Once ten people or twenty people can get a lot out of a work,

then a hundred people might. Then if a hundred people, a thousand

people ought to get it. Now if a thousand people, why not tens of

thousands? The works really start in a small group, just as Mozart

did. He had this very elite and aristocratic group of people who were

called amateurs of music, but they all played, and they realized what he

was doing was very important. They were up on it and kept abreast

of what he was doing. They weren’t behind the times, and this music

now has become very popular. Opera started at around the year 1600

by a group of sophisticated people. Scientists and aristocrats gathered

in a small group to discuss where they were going and how they would revive

Greek drama. They wrote articles which were inscrutable then, and

now those kinds of pieces appear in the music magazines in which twelve-tone

composers write. This became a very popular idiom. When you

write initially, it seems to me you write on the best level, and you don’t

think of it going to people who aren’t at the level of what you’re doing.

There’s no reason why everybody should like music, just as I’m not into

sports. I just don’t see the necessity for assuming that everyone

is going to listen to music, and then when you write music you are not

thinking of everyone. You are thinking of an audience which is at

the level of what you are doing.

AB: You really ask difficult questions! [Both

laugh] One develops a kind of peer group, and the recognition of your

peer group is very important to you because it’s some confirmation.

When I write, in a sense I write simply for myself. That sounds very

curious and elitist, but I want to sit there as an audience. I want

to say, “Is that something that I’m going to listen

to, and listen to many times?” and if I ask some of

my peers to verify my judgment, it helps me to think that I have achieved

my goal. Once ten people or twenty people can get a lot out of a work,

then a hundred people might. Then if a hundred people, a thousand

people ought to get it. Now if a thousand people, why not tens of

thousands? The works really start in a small group, just as Mozart

did. He had this very elite and aristocratic group of people who were

called amateurs of music, but they all played, and they realized what he

was doing was very important. They were up on it and kept abreast

of what he was doing. They weren’t behind the times, and this music

now has become very popular. Opera started at around the year 1600

by a group of sophisticated people. Scientists and aristocrats gathered

in a small group to discuss where they were going and how they would revive

Greek drama. They wrote articles which were inscrutable then, and

now those kinds of pieces appear in the music magazines in which twelve-tone

composers write. This became a very popular idiom. When you

write initially, it seems to me you write on the best level, and you don’t

think of it going to people who aren’t at the level of what you’re doing.

There’s no reason why everybody should like music, just as I’m not into

sports. I just don’t see the necessity for assuming that everyone

is going to listen to music, and then when you write music you are not

thinking of everyone. You are thinking of an audience which is at

the level of what you are doing. BD: [Gently protesting] But that statement presupposes

that you’ll know beforehand what’s going to be a good concert and what’s

not going to be a good concert.

BD: [Gently protesting] But that statement presupposes

that you’ll know beforehand what’s going to be a good concert and what’s

not going to be a good concert. AB: Oh, I think it’s marvelous. Recording has

been a very great thing. The unfortunate thing about recording

is that pieces don’t get recorded until they’ve made a success in concert,

and for a composer who wants to get something recorded, it’s not likely

that they can record a work that’s never been played. But it’s

good to be able to have the music where you can listen to it all the time.

I don’t mean just as background

— though I guess there’s nothing we can do about that

— but the idea that you can get close to it. The idea

that there’s a performance that presumably has been passed by the people

who let it out is a very valuable thing. I don’t know if this is quite

your question, but for students in the university it’s good and it’s bad

that they can get to know music. But it’s not to stop them from learning

how to read music, just as these new digital watches don’t show you the

point on a dial. So when you say this is quarter after twelve it doesn’t

describe something. It’s going out of fashion,

like knowing arithmetic while having a calculator. But I do think

the inventions are tremendous. Now we feel we’re more like a painter

who does something. The painting’s on the wall, rather than one concert

which, as you were saying before, is so evanescent. In the days when

you weren’t able to record our music at a concert, we had a new piece played

and all the time and the money went into a performance, and it goes in one

night. Then a composer was left with nothing to show to anybody.

I don’t know what the bad aspects of recording could be.

AB: Oh, I think it’s marvelous. Recording has

been a very great thing. The unfortunate thing about recording

is that pieces don’t get recorded until they’ve made a success in concert,

and for a composer who wants to get something recorded, it’s not likely

that they can record a work that’s never been played. But it’s

good to be able to have the music where you can listen to it all the time.

I don’t mean just as background

— though I guess there’s nothing we can do about that

— but the idea that you can get close to it. The idea

that there’s a performance that presumably has been passed by the people

who let it out is a very valuable thing. I don’t know if this is quite

your question, but for students in the university it’s good and it’s bad

that they can get to know music. But it’s not to stop them from learning

how to read music, just as these new digital watches don’t show you the

point on a dial. So when you say this is quarter after twelve it doesn’t

describe something. It’s going out of fashion,

like knowing arithmetic while having a calculator. But I do think

the inventions are tremendous. Now we feel we’re more like a painter

who does something. The painting’s on the wall, rather than one concert

which, as you were saying before, is so evanescent. In the days when

you weren’t able to record our music at a concert, we had a new piece played

and all the time and the money went into a performance, and it goes in one

night. Then a composer was left with nothing to show to anybody.

I don’t know what the bad aspects of recording could be.  AB: I think it was the poet Paul Valery

(1871-1945) who said that you just come to a point and you stop.

[An artist never really finishes his work, he merely abandons it.]

You set out with the idea that you want to accomplish a certain

number of things in the course of the piece. Right now you don’t

have the form that at one time would have given us the place to stop.

Now we do — or at least I do, and a lot of us do

— what is more like a variation form. So you’re going around

and around in dealing with the same material, and you come to a point where

you feel you’ve exhausted the number of transformations that you have for

this particular piece. You also have the feeling that it’s properly

balanced, and that it’s long enough in terms of being tired of what you’ve

been hearing. It comes to a point when indeed it rounds up to something

that’s been there before. I’m very, very careful about beginnings

and endings. The feeling at a beginning is that the audience is immediately

taken into a piece; it really has your attention. Then the end is

convincing in terms that it really does wind down. Or, if you want

them to have a really big ending, maybe a ‘bravura’ ending, there it does

have the vision of an ending. I must say that it is a very valid question

because the notion of where a thing should stop is not what it used to be

right now. Very often in a lot of music right now one could say you’re

just stopping it. If you take John Cage, it’s like wallpaper.

If a piece goes on for twenty-four hours, you can come in and go out.

So there are tendencies right now where music is additive and continuous

in that way. I’m not religious about this idea that you have to perform

four movements of a work, for example. In the old days the composers

did not object to having one or two movements of their work. The four

movements gave a certain completeness, like in a concert, but that doesn’t

mean you’re destroying it by not performing the whole. I’m not so crazed

if the work is continuous and the movement doesn’t end, but I don’t think

it’s a terribly serious thing as far as where a work goes. I don’t

know whether it’s organic like a human being, and I may be quite insane saying

that.

AB: I think it was the poet Paul Valery

(1871-1945) who said that you just come to a point and you stop.

[An artist never really finishes his work, he merely abandons it.]

You set out with the idea that you want to accomplish a certain

number of things in the course of the piece. Right now you don’t

have the form that at one time would have given us the place to stop.

Now we do — or at least I do, and a lot of us do

— what is more like a variation form. So you’re going around

and around in dealing with the same material, and you come to a point where

you feel you’ve exhausted the number of transformations that you have for

this particular piece. You also have the feeling that it’s properly

balanced, and that it’s long enough in terms of being tired of what you’ve

been hearing. It comes to a point when indeed it rounds up to something

that’s been there before. I’m very, very careful about beginnings

and endings. The feeling at a beginning is that the audience is immediately

taken into a piece; it really has your attention. Then the end is

convincing in terms that it really does wind down. Or, if you want

them to have a really big ending, maybe a ‘bravura’ ending, there it does

have the vision of an ending. I must say that it is a very valid question

because the notion of where a thing should stop is not what it used to be

right now. Very often in a lot of music right now one could say you’re

just stopping it. If you take John Cage, it’s like wallpaper.

If a piece goes on for twenty-four hours, you can come in and go out.

So there are tendencies right now where music is additive and continuous

in that way. I’m not religious about this idea that you have to perform

four movements of a work, for example. In the old days the composers

did not object to having one or two movements of their work. The four

movements gave a certain completeness, like in a concert, but that doesn’t

mean you’re destroying it by not performing the whole. I’m not so crazed

if the work is continuous and the movement doesn’t end, but I don’t think

it’s a terribly serious thing as far as where a work goes. I don’t

know whether it’s organic like a human being, and I may be quite insane saying

that.

|

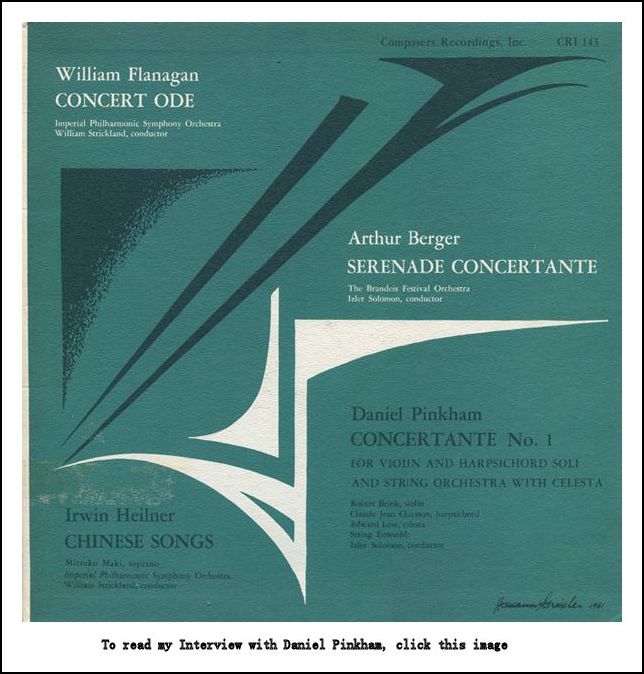

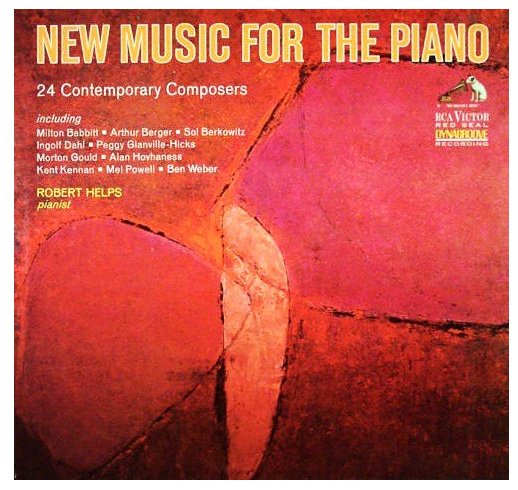

Robert Helps in a 20th

Century compendium "New Music for the Piano: 24 Contemporary Composers,"

Ingolf Dahl's Fanfares (1958), Arthur

Berger's Two Episodes (1933),

Kent Kennan's

Two Preludes (1951), Samuel Adler's Capriccio (1954), Hall Overton's Polarities No. 1 (1958), Milton Babbit's

Partitions (1957), Miriam Gideon's Piano Suite No. 3 (1951), Sol Berkowitz's

Syncopations (1958), Ben

Weber's Humoreske op. 49

(1958), Leo Kraft's

Allegro Giocoso (1957), Paul A. Pisk's Nocturnal Interlude (undated), Mel Powell's Etude (1957), Morton Gould's Rag-Blues-Rag (undated), Vivian Fine's Sinfonia and Fugato (undated), Alan Hovhaness' Allegro on a Pakistan Little Tune op. 104 No.

6 (1952), George

Perle's Six Preludes op. 20B

(1946), Norman Cazden's Sonata op. 53

No.3 (1950), Joseph Prostakoff's Two Bagatelles (undated), Ernst Bacon's The Pig Town Fling (undated), Helps's

Image (1957), Mark Brunswick's

Six Bagatelles (1958), Earl Kim's Two Bagatelles (1950/1948), and Josef Alexander's Incantation (1964). Underwritten by The Abbey Whiteside Foundation. Cover art is by Sid Maurer. Glossy full-size 10-page booklet with extensive notes on all composers and works featured herein, written by Joseph Prostakoff. The RCA LP was originally issued in 1966, and later re-issued on CRI in 1971. When it was re-mastered and issued on a CRI CD in 2001, the works by Berger, Kraft, and Fine were omitted. |

AB: No! It’s a very difficult time now. [Pauses

a moment] I really don’t know. There was an article by John

Rockwell in The New York Times, putting forward the theory that the

intellectual-modernist view of music was over. He said that Serialism

is at an end, Modern Music is at an end, and the New Romanticism is here.

We’ve got to write music which sounds like Berlioz or Rachmaninoff

or Brahms now. So I wrote an article [published in the Boston Review,

February, 1987] called Is There a Post-Modern Music? I tried

to make the case, first of all, that these romantic revivals happen from

time to time over the period, and it isn’t new in any case. What’s

the use of a work in which you appropriate the music you already have? We

have enough romantic works that we have no time to listen to. Who needs

more of them? Insofar as Serialism is concerned, I compare it what

happened around 1900 and the first decade of this century. In 1600,

when monody first came in after polyphony, monody took a century and a

half to develop into Haydn and Mozart. Serialism might take another

century or so before it develops into something. It is something that

we have to nurture, but there are signs that people don’t want to nurture

it. They want something new. So the reason I’m not optimistic

is I’m worried about what will happen if they’re so impatient that they can’t

wait for something new. They will destroy something, and just destroy

the whole thing to bring it to an end. After all, music doesn’t have

to be an art where Serialist music goes on forever. Perhaps it won’t.

There wasn’t much music before, let’s say, 1200 AD, or 1500 AD.

Maybe our new style isn’t for all times.

AB: No! It’s a very difficult time now. [Pauses

a moment] I really don’t know. There was an article by John

Rockwell in The New York Times, putting forward the theory that the

intellectual-modernist view of music was over. He said that Serialism

is at an end, Modern Music is at an end, and the New Romanticism is here.

We’ve got to write music which sounds like Berlioz or Rachmaninoff

or Brahms now. So I wrote an article [published in the Boston Review,

February, 1987] called Is There a Post-Modern Music? I tried

to make the case, first of all, that these romantic revivals happen from

time to time over the period, and it isn’t new in any case. What’s

the use of a work in which you appropriate the music you already have? We

have enough romantic works that we have no time to listen to. Who needs

more of them? Insofar as Serialism is concerned, I compare it what

happened around 1900 and the first decade of this century. In 1600,

when monody first came in after polyphony, monody took a century and a

half to develop into Haydn and Mozart. Serialism might take another

century or so before it develops into something. It is something that

we have to nurture, but there are signs that people don’t want to nurture

it. They want something new. So the reason I’m not optimistic

is I’m worried about what will happen if they’re so impatient that they can’t

wait for something new. They will destroy something, and just destroy

the whole thing to bring it to an end. After all, music doesn’t have

to be an art where Serialist music goes on forever. Perhaps it won’t.

There wasn’t much music before, let’s say, 1200 AD, or 1500 AD.

Maybe our new style isn’t for all times.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on March 28, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB about six weeks later, and again in 1992 and 1997. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.