Leonard

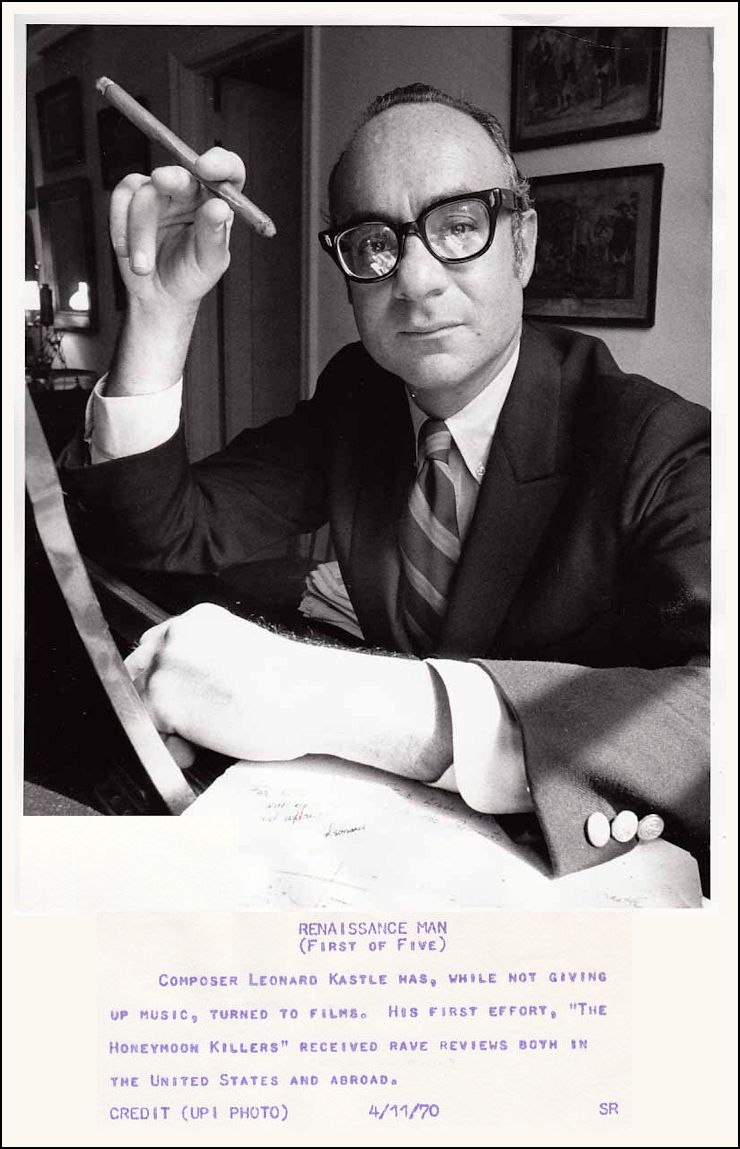

Kastle dies at 82; writer-director of 'The Honeymoon Killers'

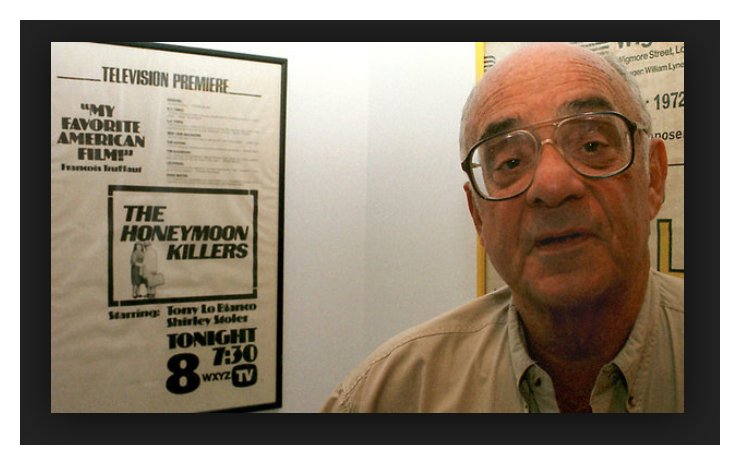

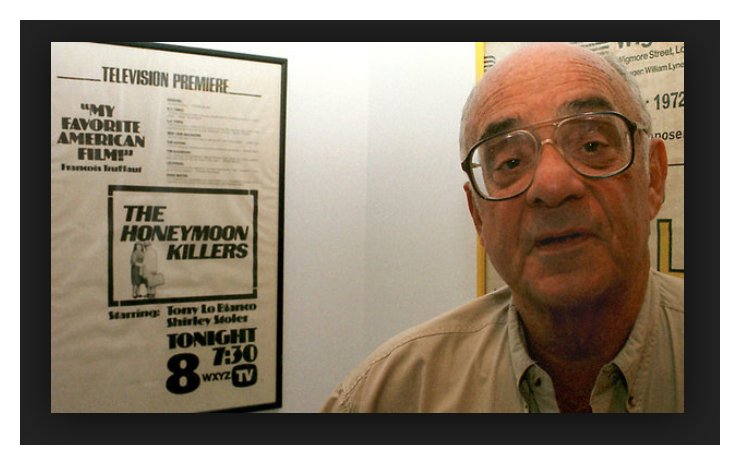

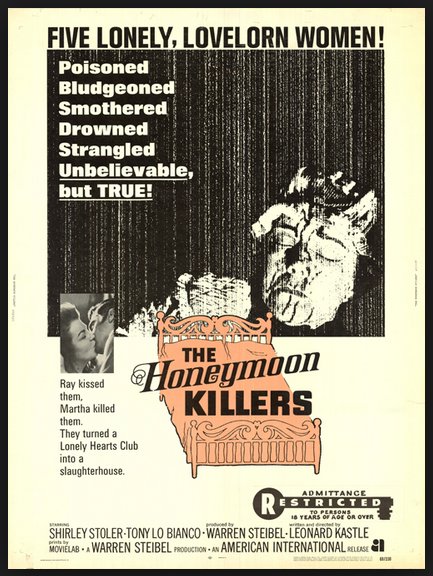

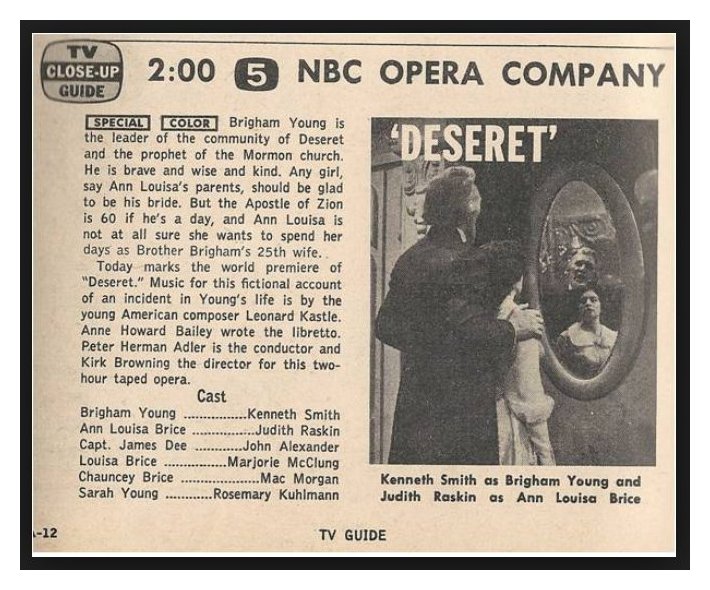

Leonard Kastle's only movie, released in 1970, was hailed for its pure, grim realism. He also wrote operas and other compositions and taught at the State University of New York in Albany. May 29, 2011 By Dennis McLellan, Los Angeles Times [text only - photo from another source] When Leonard Kastle's debut movie as a writer and director, "The Honeymoon Killers," was released in 1970, critics raved over the grimly realistic, low-budget, black-and-white crime drama about a lowlife lothario and his overweight nurse lover whose partnership in conning lonely women leads to murder. French director Francois Truffaut called it his "favorite American film." Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni considered it "one of the purest movies I've ever seen." Kastle, whose first film was destined to be his last, died May 18 at his home in Westerlo, N.Y., after a brief illness, said Tina Sisson, a friend. He was 82. Kastle is considered one of America's most intriguing one-shot movie directors. Neither he nor producer Warren Steibel had any filmmaking experience when they set out to make "The Honeymoon Killers," which gained cult status in America and Europe. Kastle was an opera composer whose work had aired on television, and Steibel was the producer of William F. Buckley Jr.'s TV series "Firing Line." But after a wealthy friend of Steibel's agreed to put up $150,000 to finance a low-budget movie, Steibel asked his friend Kastle to write the script. "The Honeymoon Killers" was based on the true-life story of Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez, the so-called Lonely Hearts Killers who were executed at New York's Sing Sing prison in 1951. The movie was shot on location in and near Albany, N.Y., in eight weeks, with Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco playing Beck and Fernandez. The film's original director was a young Martin Scorsese. But Scorsese's filmmaking pace was too slow and he was soon removed. Industrial filmmaker Donald Volkman then stepped in for a time before Kastle took over as the credited director. Like Steibel, Kastle envisioned the movie as a starkly realistic contrast to "Bonnie and Clyde," starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. "I was revolted by that movie," Kastle said in an interview on the 2003 Criterion Collection reissue of the film on DVD. "I didn't want to show beautiful shots of beautiful people."

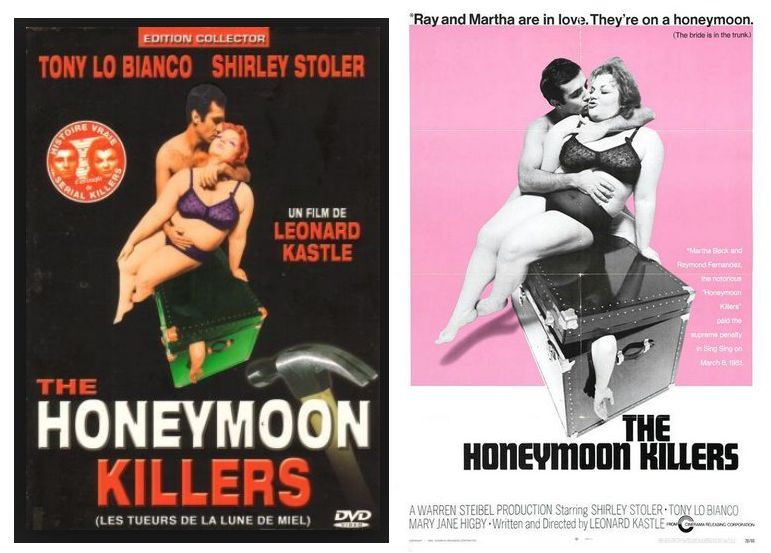

"'The Honeymoon Killers,'" The Times' Kevin Thomas wrote in his 1970 review, "is the kind of movie that restores your faith in the possibilities for the commercial American cinema." "This extraordinary little movie," Thomas wrote, "belongs to that long but now virtually extinct line of B movies that examines the dark side of American life with a perception and honesty traditionally lacking in our expensive escapist fare." In his review of the film in The New York Times, Roger Greenspun described Kastle as "the real star of the movie," saying that his direction placed him "among the important deliberate artists of his medium." But then Kastle vanished from the world of cinema, to the point that two decades later Daily Variety's Todd McCarthy was telling readers that Kastle was one of the directors about whom people most often asked him, "Whatever happened to?" "No one," McCarthy wrote when "The Honeymoon Killers" was re-released in theaters in 1992, "ever disappeared faster and more mysteriously than Kastle." After making the film, Kastle returned to composing and later began teaching — not that he didn't try to make a big-screen comeback. He wrote a number of screenplays over the years. And for decades, he tried to make "The Wedding at Cana," his story of corruption involving the Catholic Church and organized crime set in the 1970s. He came closest to making the film in 2001, but financing fell through. "It was a lot of almosts and near-misses," Kastle said of the failed project in a 2001 interview with the Albany Times-Union. "I felt like Sisyphus rolling the stone up the hill." But, as Kastle wryly pointed out in his interview for the Criterion DVD, he at least was always able to say, "I never made a bad film after 'Honeymoon Killers.' " The son of Russian immigrants, he was born in New York City on Feb. 11, 1929, and grew up in Mount Vernon, N.Y. A child prodigy, he began his musical training at the Juilliard School in 1938. After studying piano and composition at the Mannes Music School (now Mannes College) in Manhattan, he earned a bachelor's degree from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia in 1950. His early career included serving as assistant musical director and conductor for "NBC Television Opera Theater" from 1955 to 1959, during which he directed his own one-act opera, "The Swing." NBC also aired his three-act opera, "Deseret," in 1961. Other Kastle operas are "The Pariahs," "The Passion of Mother Ann: A Sacred Festival Play" (a trilogy), and a one-act children's opera, "Professor Lookalike and the Children." Kastle, who also wrote orchestral works and songs, taught composition and other classes at the State University of New York in Albany (now the University at Albany) from 1978 to 1989. He is survived by his sister, Norma Merker of San Francisco. |

| *Irving Kolodin (February 21, 1908 – April

29, 1988) was an American music critic and music historian. Kolodin was born in New York City. He wrote for the New York Sun from 1932 to 1950 and for the Saturday Review starting in 1947. He was best known for his popular Guide to Recorded Music. He also wrote program notes for the New York Philharmonic and Metropolitan Opera, and a 762 page "candid history" of the Met up to 1966. ================== **Winthrop Sargeant (December 10, 1903, San Francisco, California – August 15, 1986, Salisbury, Connecticut) was an American music critic, violinist, and writer. He studied the violin in his native city with Albert Elkus and with Felix Prohaska and Lucien Capet in Europe. In 1922, at the age of 18, he became the youngest member of the San Francisco Symphony. He left there for New York City in 1926 where he became a violinist with the New York Symphony (1926–28) and later the New York Philharmonic (1928–30). He abandoned his performance career in favour of pursuing a career as a journalist, critic, and writer in 1930. He wrote music criticism for Musical America, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and The New York American. He was notably a music editor for Time magazine from 1937–1945, and he served as a senior writer for Life magazine from 1945–1949. From 1949-1972 he wrote the column Musical Events for The New Yorker. He continued to write music criticism for that publication up until his death in 1986 at the age of 82. His books included Jazz: Hot and Hybrid (1938), Geniuses, goddesses, and people (1949), Listening to music (1958), Jazz: a history (1964), In spite of myself: a personal memoir (1970), Divas (1973). ================== Former Tribune Music Critic Albert

Goldberg

February 11, 1990|By John von Rhein, Chicago Tribune ***Albert Goldberg, a distinguished former music critic of the Chicago Tribune and a music critic for the Los Angeles Times since 1947, died Feb. 4 in Nashville, Tenn., where he had been hospitalized for a broken vertebra. He was 91. Born in Shenandoah, Iowa, Mr. Goldberg studied at Chicago`s Gunn School of Music and in 1935 became Illinois director of the Federal Music Project, a Depression-era program under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration. From 1935 to 1943, he and Izler Solomon were co-conductors of the federally sponsored Illinois Symphony, a 90-member orchestra that performed for audiences who paid 25 cents a seat at Chicago`s old Great Northern Theater. During its brief history the ensemble gave the first local performances of some 150 works. Mr. Goldberg and Solomon earned from $90 to $100 a month for their efforts. They rehearsed six times a week under federal guidelines that required the exclusive use of unemployed musicians. A pianist by training, Mr. Goldberg worked as a music critic at the old Chicago Herald and Examiner before joining the Tribune`s arts staff in 1943 at the invitation of chief critic Claudia Cassidy. He wrote reviews for the Tribune until he became chief music critic of the Los Angeles Times in 1947. ``We hated to lose him,`` Cassidy recalls. ``He was a dear friend, a valuable person to have at the paper, wonderful at getting the (critics) department established. His death removes someone very remarkable from our thinning ranks.`` A man of wide culture and discerning taste, Mr. Goldberg was known for the elegance, point and evenhanded nature of his criticism. He wrote witty and graceful reminiscences of some of the greatest musicians of his era, including Percy Grainger, Lauritz Melchior, Josef Hoffman, Arthur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz, whom he adored. He also was a staunch defender of conductor Georg Solti during the latter`s beleaguered, short-lived term as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the early 1960s. Mr. Goldberg was considered the first of the serious musical commentators in Los Angeles, drawing regular fire from the arts establishment but sticking to his critical guns. Although he retired as Times music critic in 1965, he continued to contribute reviews and feature articles until shortly before his death. Survivors include a niece, Sandy McSeveney, of Nashville, Tenn. = = = = = = =

Albert Goldberg: An Appreciation

February 06, 1990|MARTIN BERNHEIMER | LOS ANGELES TIMES MUSIC CRITIC Albert Goldberg, who died on Sunday, wasn't like other music critics. He served time, early in his distinguished career, as a pianist and conductor. He lived with music and for music, with a little time out for decent literature and fine food. Unlike some of us, he didn't like going to movies on a free night. He switched on his infernal, newfangled television set only under duress and then only with careful, often futile instruction. He couldn't stop learning about the things he deemed important. He considered a biography of Franz Liszt good bed-time reading. Only a few months ago, he called to chat about his excitement at rediscovering some ancient recordings by Enrico Caruso. Tenors today, he muttered, don't have that sort of dynamic finesse. He couldn't stop writing. He typed his last piece for this paper--a perceptive review of Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic--on March 21, 1989. That was three months before his 91st birthday. We didn't know at the time that this would be his critical swan song, but the subject turned out to be apt. He had been one of Mehta's earliest, staunchest and most persuasive supporters. Albert always attended concerts even when he didn't have to. He went eagerly. He went compulsively. That probably helped keep him young. He could remember Kreisler, but was curious about Anne Sophie Mutter. He grew up with Toscanini and, formatively, with Frederick Stock, but wanted to know all about Esa-Pekka Salonen. He recalled Paderewski and worshipped Horowitz, but mustered great interest in Jean-Yves Thibaudet. His aesthetic priorities were wonderfully quirky. A discerning romanticist from Shenandoah, Iowa, he tended to find Bach dry, Figaro long, modern music unpleasant. Yet he was always willing--and pleased--to be surprised. His sense of humor did not preclude occasional excursions into self-mockery. He was, essentially, a gentleman of the old school. He respected common courtesies, and uncommon ones too. No one confused him, however, with the traditional mild-mannered reporter. He once engaged none less than Igor Stravinsky in a feisty public battle of wits and priorities. In the distant past when the extramusical powers at The Times attacked Georg Solti--then the beleaguered and short-lived music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic--Albert refused to toe the line. He kept his integrity. He was a stylist. His deceptively gentle prose revealed elegance, balance, point. He was a scholar. He knew far more about the piano, about pianists and about the piano literature than most of us could ever hope to know. He also was a generous colleague. When in 1965 he reached official retirement age--actually he had exceeded it by a couple of years--he had to contend with a brash young writer from New York invading what had been his turf. Others in his position might have registered resentment. Others might have withdrawn and waited gleefully for the foolhardy newcomer to make an ass of himself. Albert Goldberg did nothing of the kind. He stepped aside, offered help and voiced encouragement. A quarter of a century later, the foolhardy newcomer still thanks him for that. |

BD: [With a gentle nudge]

Is Leonard Kastle an interesting person?

BD: [With a gentle nudge]

Is Leonard Kastle an interesting person? LK: Yes! It has to be. It’s a lot

of fun. It can be very, very frustrating. I generally march

around for a quite while being very unhappy and putting it off, and fighting

to keep away from it. When I’m starting something my house is so clean

you wouldn’t believe it. I’m vacuuming all day long. I’m sure

it applies to everything creative, whether it’s a book or a poem or a painting,

but there is an invasion of an unknown territory, and an invasion very often

doesn’t succeed. You make a beachhead with a little idea, perhaps,

and it’s a little tiny beachhead on this invasion to the unknown world of

creating something out of nothing. This is how you should compose,

and I wish a lot of composers, who don’t write that way, did. Then

sometimes it gets wiped out. Very often it gets wiped out and you tear

it up, or you never continue with it because for some reason the beachhead

wasn’t inspiring enough for you. At least this is how I compose, and

it always works out that way. That beachhead is like the landing when

Eisenhower invaded Europe and the supplies started coming. If that

beachhead is valid and inspiring, it’s amazing what can come out of

a little beachhead. A beautiful piece of music, or any great art, is

something God made. It’s like a tree which starts to grow and starts

to leaf out, and when it leafs out, everything starts to affect everything

that you began with. Then it really starts to grow, and then it has

life and it has shape and it has validity. But it’s very hard.

I think that’s the way you have to compose. You don’t just add measures

on. You have to have a real idea. Any great work of art is like

that. I’ve been teaching the Ring

lately. It’s one of the courses I like to add to the curriculum.

There were 106 students in my last class, which is rather incredible.

LK: Yes! It has to be. It’s a lot

of fun. It can be very, very frustrating. I generally march

around for a quite while being very unhappy and putting it off, and fighting

to keep away from it. When I’m starting something my house is so clean

you wouldn’t believe it. I’m vacuuming all day long. I’m sure

it applies to everything creative, whether it’s a book or a poem or a painting,

but there is an invasion of an unknown territory, and an invasion very often

doesn’t succeed. You make a beachhead with a little idea, perhaps,

and it’s a little tiny beachhead on this invasion to the unknown world of

creating something out of nothing. This is how you should compose,

and I wish a lot of composers, who don’t write that way, did. Then

sometimes it gets wiped out. Very often it gets wiped out and you tear

it up, or you never continue with it because for some reason the beachhead

wasn’t inspiring enough for you. At least this is how I compose, and

it always works out that way. That beachhead is like the landing when

Eisenhower invaded Europe and the supplies started coming. If that

beachhead is valid and inspiring, it’s amazing what can come out of

a little beachhead. A beautiful piece of music, or any great art, is

something God made. It’s like a tree which starts to grow and starts

to leaf out, and when it leafs out, everything starts to affect everything

that you began with. Then it really starts to grow, and then it has

life and it has shape and it has validity. But it’s very hard.

I think that’s the way you have to compose. You don’t just add measures

on. You have to have a real idea. Any great work of art is like

that. I’ve been teaching the Ring

lately. It’s one of the courses I like to add to the curriculum.

There were 106 students in my last class, which is rather incredible.  LK: Yes, I think it works... it could work.

It’s a big compromise, but I think it’s here especially if an opera is written

for television. I think it will work a lot. I’m writing a lot

of stuff! Nothing stops me! I got a commission last spring from

the New York Arts Council for the Albany School district, and I wrote children’s

opera. They asked me to write an opera about racial understanding.

We have a school here in Albany called Albany Hill, and it is a really marvelous

school that’s all minority. We have Afghanistan kids, we have black

kids, we have Puerto Rican kids, we have East Indian kids and Asian kids...

So they asked me if I’d work with them, and I wrote an opera called Professor Lookalike and the Children.

Professor Lookalike is a crazy professor — I’ve known

plenty of them — and he invents a pill. He’s

got all these pills, they’re called ‘lookalike pills’

and they’re kept under lock and key. The first

child takes the first pill, and then every other child who takes a pill

after that will look ethnically just like that first child. The whole

opera is really for television, and I’m hopeful I’m going to get it on television.

It’s really rather charming. There’s somebody

quite interested in doing it. The whole opera is a meeting of the

legislature. We set it in New York, and the Governor calls a special

session of the New York legislature to enact legislation about what that

first child should be. Professor Lookalike is one of the witnesses,

and he comes with all of his pills guarded by State troopers. Then

there’s an ethnologist who’s a witness, and an anthropologist is a witness,

and they debate. Of course, the black one says to make them all black

to make up for slavery, and the light one says, no make them all light.

They argue and get to a stalemate, and one of them keeps saying, “Why

not make them both Hispanic,” at which point the whole

orchestra starts playing a Habanera. They say, “We’re

at a stalemate! We’re in a muddle! We’re in a mishmash!

We’re in the wrong opera!” [Both laugh]

Then suddenly all these kids from this school come in and break up the meeting.

They have decided among themselves which child should take the first pill,

and they’ve elected five kids to speak to them. One is black, one

is Hispanic, one is Japanese, one is Arab, and one is white. So they

let the kids decide, and it’s really adorable what happens at the end.

That is really a TV opera. When I wrote it I knew it had to be done

on the stage, but it’s really for TV, like Amahl by Menotti. Amahl is marvelous on TV. I think

operas should be written for television. I worked for the NBC Opera

for several years before they did Deseret.

I was the vocal coach and translator for an assistant conductor, and we did

The Marriage of Figaro in two parts,

and we did Salome, and Macbeth by Verdi. I thought it

was very, very successful. One of the reasons why it’s very successful

is you can have people who look the part because they don’t have to sing

out into an enormous hall. So it can be much more realistic and dramatic.

We did everything in English, and of course if it’s on television you understand

every word. You don’t need titles.

LK: Yes, I think it works... it could work.

It’s a big compromise, but I think it’s here especially if an opera is written

for television. I think it will work a lot. I’m writing a lot

of stuff! Nothing stops me! I got a commission last spring from

the New York Arts Council for the Albany School district, and I wrote children’s

opera. They asked me to write an opera about racial understanding.

We have a school here in Albany called Albany Hill, and it is a really marvelous

school that’s all minority. We have Afghanistan kids, we have black

kids, we have Puerto Rican kids, we have East Indian kids and Asian kids...

So they asked me if I’d work with them, and I wrote an opera called Professor Lookalike and the Children.

Professor Lookalike is a crazy professor — I’ve known

plenty of them — and he invents a pill. He’s

got all these pills, they’re called ‘lookalike pills’

and they’re kept under lock and key. The first

child takes the first pill, and then every other child who takes a pill

after that will look ethnically just like that first child. The whole

opera is really for television, and I’m hopeful I’m going to get it on television.

It’s really rather charming. There’s somebody

quite interested in doing it. The whole opera is a meeting of the

legislature. We set it in New York, and the Governor calls a special

session of the New York legislature to enact legislation about what that

first child should be. Professor Lookalike is one of the witnesses,

and he comes with all of his pills guarded by State troopers. Then

there’s an ethnologist who’s a witness, and an anthropologist is a witness,

and they debate. Of course, the black one says to make them all black

to make up for slavery, and the light one says, no make them all light.

They argue and get to a stalemate, and one of them keeps saying, “Why

not make them both Hispanic,” at which point the whole

orchestra starts playing a Habanera. They say, “We’re

at a stalemate! We’re in a muddle! We’re in a mishmash!

We’re in the wrong opera!” [Both laugh]

Then suddenly all these kids from this school come in and break up the meeting.

They have decided among themselves which child should take the first pill,

and they’ve elected five kids to speak to them. One is black, one

is Hispanic, one is Japanese, one is Arab, and one is white. So they

let the kids decide, and it’s really adorable what happens at the end.

That is really a TV opera. When I wrote it I knew it had to be done

on the stage, but it’s really for TV, like Amahl by Menotti. Amahl is marvelous on TV. I think

operas should be written for television. I worked for the NBC Opera

for several years before they did Deseret.

I was the vocal coach and translator for an assistant conductor, and we did

The Marriage of Figaro in two parts,

and we did Salome, and Macbeth by Verdi. I thought it

was very, very successful. One of the reasons why it’s very successful

is you can have people who look the part because they don’t have to sing

out into an enormous hall. So it can be much more realistic and dramatic.

We did everything in English, and of course if it’s on television you understand

every word. You don’t need titles. BD:

This is great! You’re making converts to the cause!

BD:

This is great! You’re making converts to the cause!

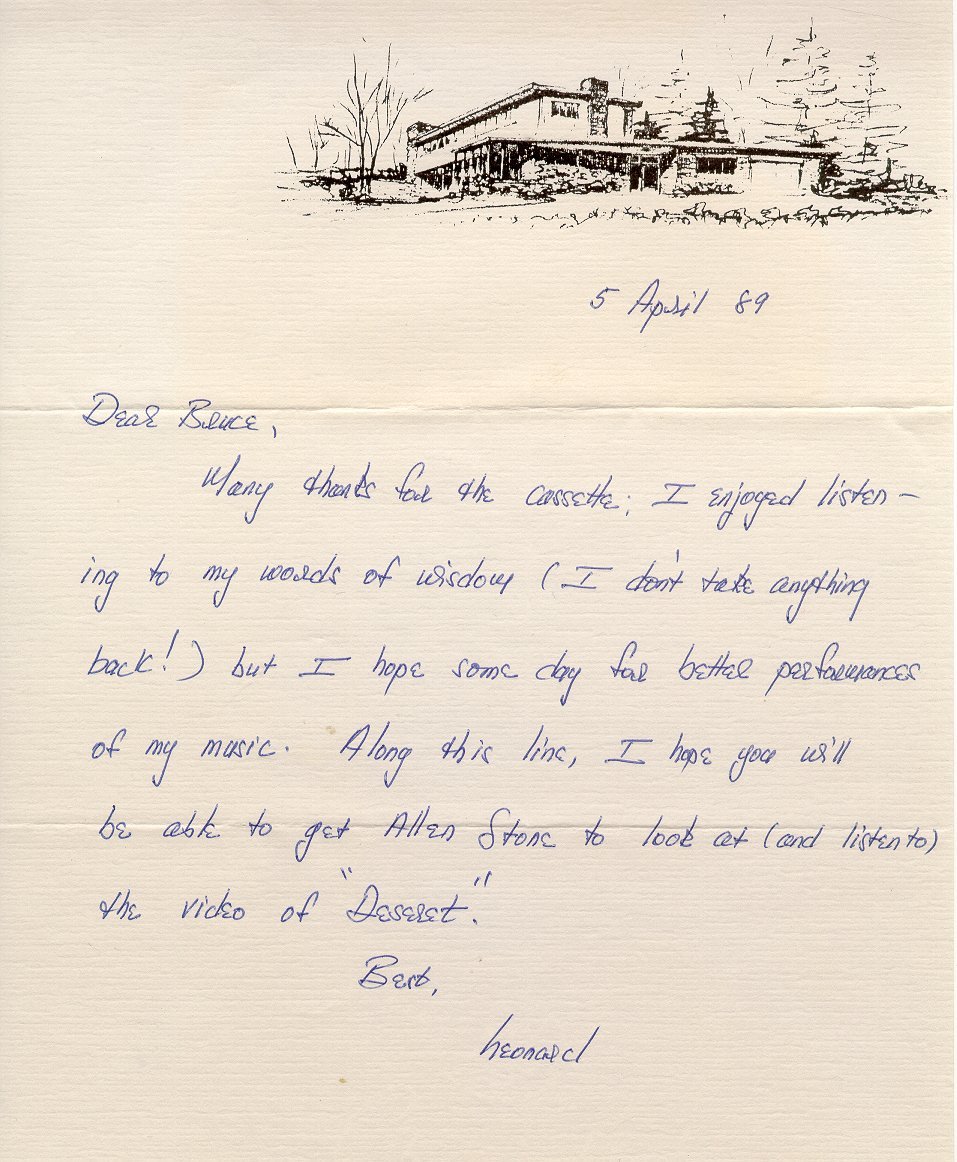

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on October 23, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB about four months later. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.