BD: You say there are many ways to say the same

thing. Does your idea of how to say it change over the years?

BD: You say there are many ways to say the same

thing. Does your idea of how to say it change over the years?

BD: In the competition which bears your name, you

always insist that there be a new piece included.

BD: In the competition which bears your name, you

always insist that there be a new piece included.

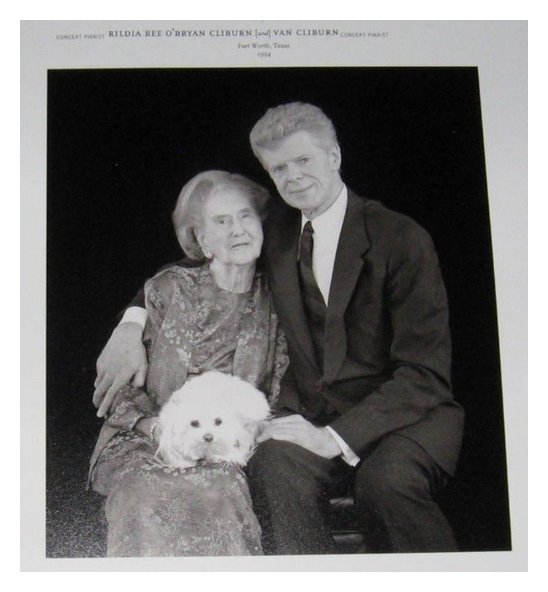

VC: This depends upon how long you have the opportunity

to practice on it. My mother [shown

with her son at left] was my only teacher until I was seventeen, and

she had wonderful experience with her teacher in New York, who was Arthur

Friedheim (1850-1932), who was a pupil of Liszt. One of the things that

she always said was, “When you go, it is your duty to make whatever instrument

is given you to work.”

VC: This depends upon how long you have the opportunity

to practice on it. My mother [shown

with her son at left] was my only teacher until I was seventeen, and

she had wonderful experience with her teacher in New York, who was Arthur

Friedheim (1850-1932), who was a pupil of Liszt. One of the things that

she always said was, “When you go, it is your duty to make whatever instrument

is given you to work.”

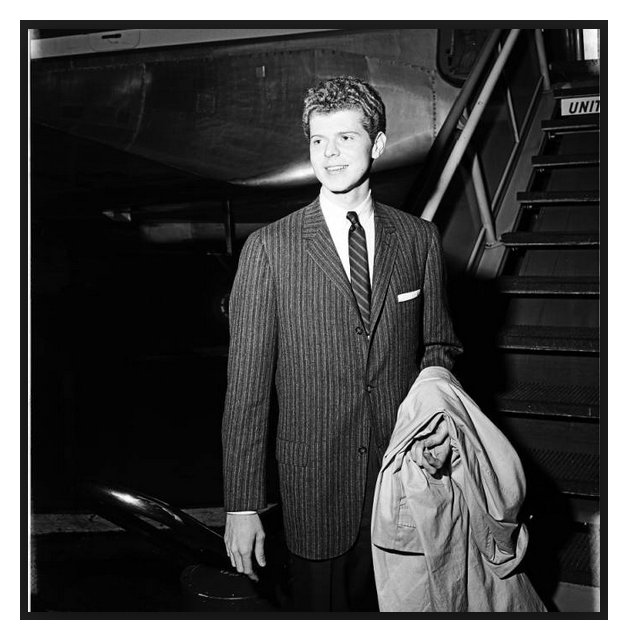

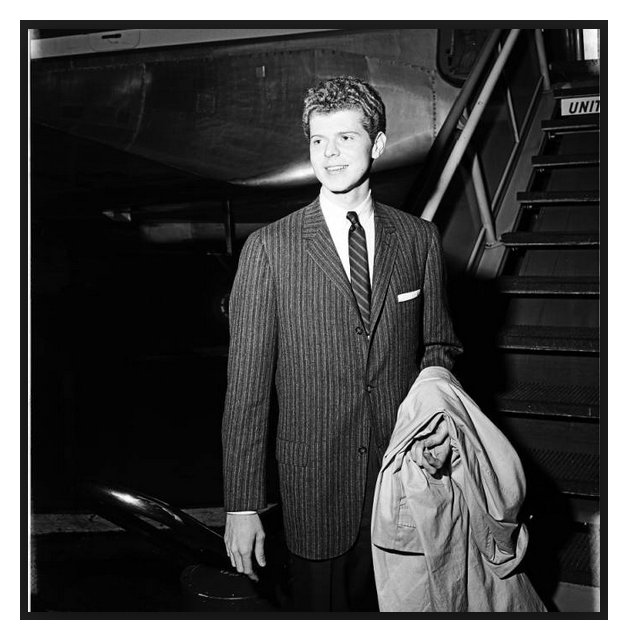

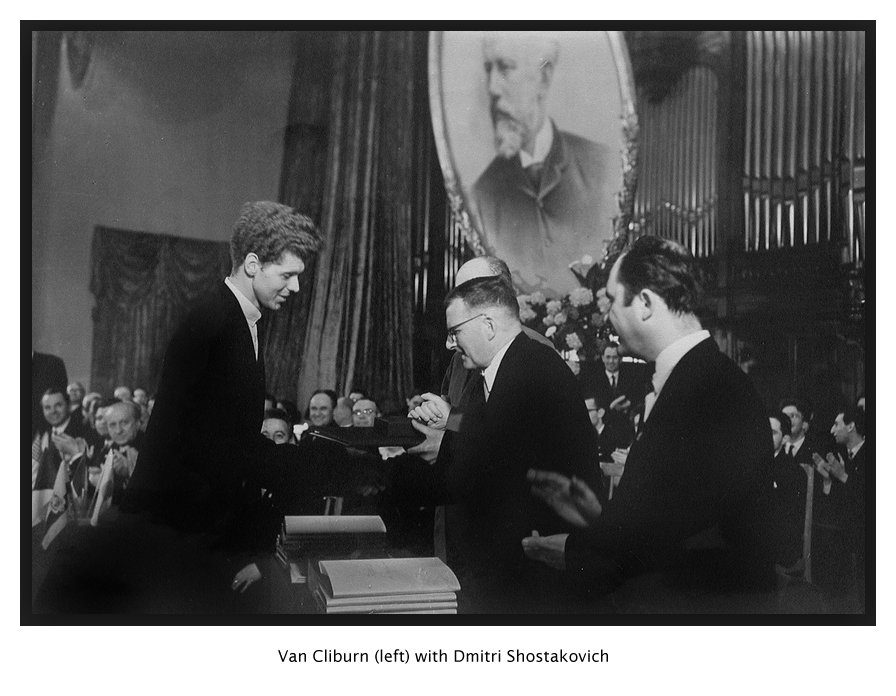

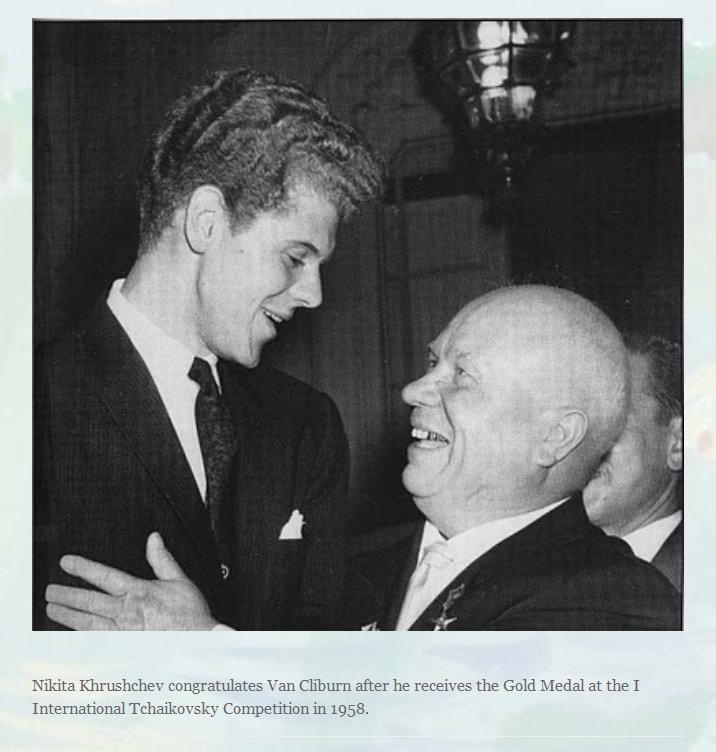

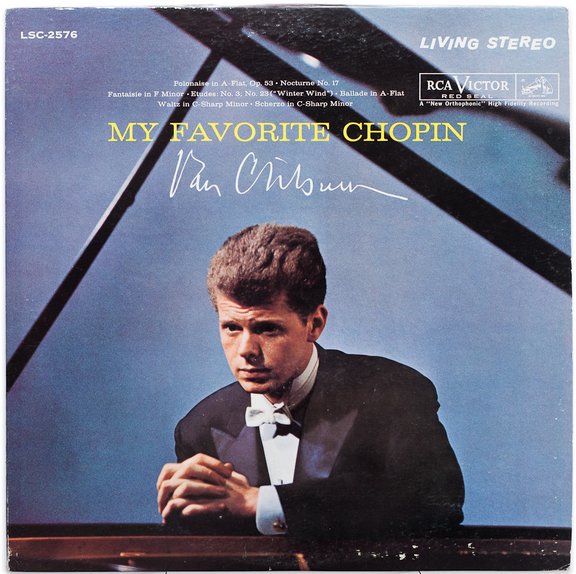

| Van Cliburn (July 12, 1934 – February

27, 2013) was born in Shreveport, Louisiana. His father, Harvey Lavan Cliburn,

was an executive with Magnolia Petroleum, now ExxonMobil. At the age of 3,

he began piano studies with his mother, Rildia Bee O’Bryan Cliburn, a talented

student of Arthur Friedheim, who was a pupil of Franz Liszt. He was 12 when

he made his orchestral debut with the Houston Symphony Orchestra. After graduating

from Kilgore High School in the spring of 1951, his mother wanted him to study

with Madame Rosina Lhevinne at the famed Juilliard School in New York City. In 1954, Van Cliburn won the Levintritt Competition, which had not awarded a first-place prize since 1949. The prestigious Levintritt Competition offered important appearances with such major orchestras as Cleveland, Denver, Indianapolis, and Pittsburgh, as well as a coveted New York Philharmonic debut with the great Dimitri Mitropoulos, which took place in Carnegie Hall on November 14, 1954. He was hailed as one of the most persuasive ambassadors of American culture, as well as one of the greatest pianists in the history of music. With his historic 1958 victory at the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, at the height of the Cold War, Van Cliburn tore down cultural barriers years ahead of glasnost and perestroika, transcending politics by demonstrating the universality of classical music.

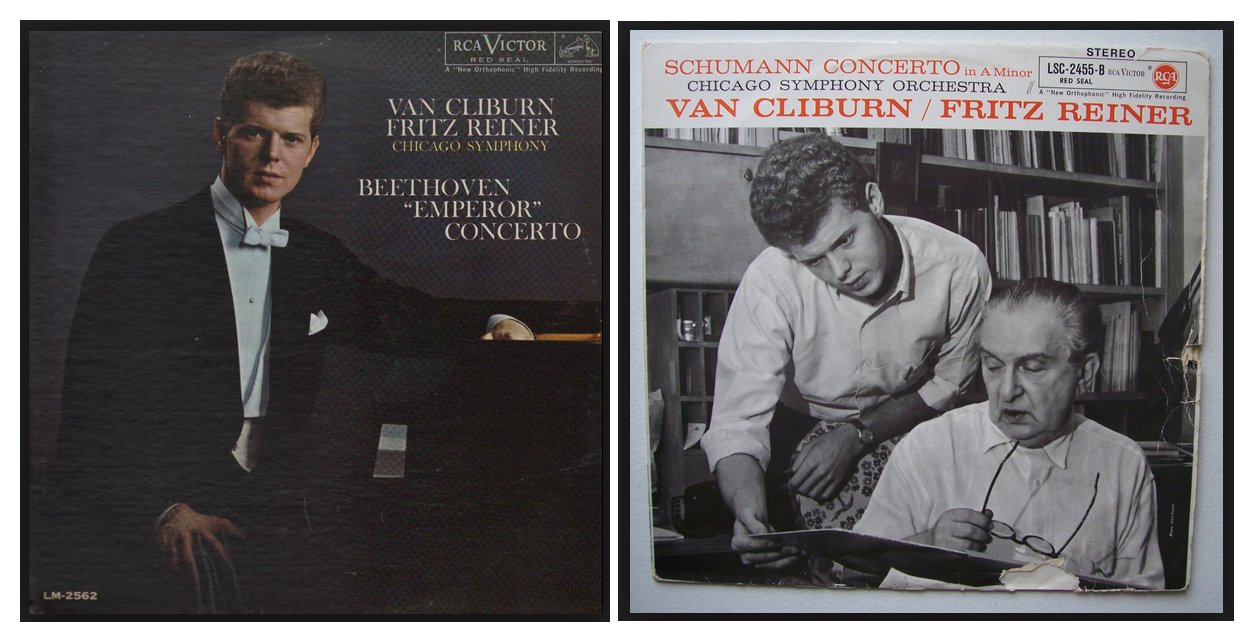

Returning home from Moscow, Mr. Cliburn received a ticker-tape parade in New York City, the only time a classical musician was ever honored with the highest tribute possible by the City of New York. Upon Mr. Cliburn’s invitation, Kiril Kondrashin, the conductor with whom the pianist had played his prizewinning performances, came from Moscow to repeat the celebrated concert program with Van Cliburn at Carnegie Hall in New York, at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, and in Washington, D.C. Their recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, made during Kondrashin’s visit, was the first classical recording ever to be awarded a platinum record and has now sold well over three million copies.

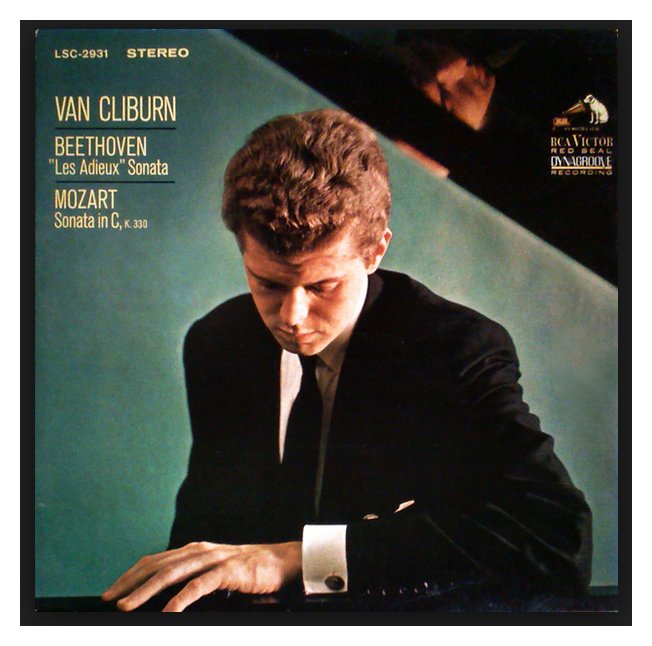

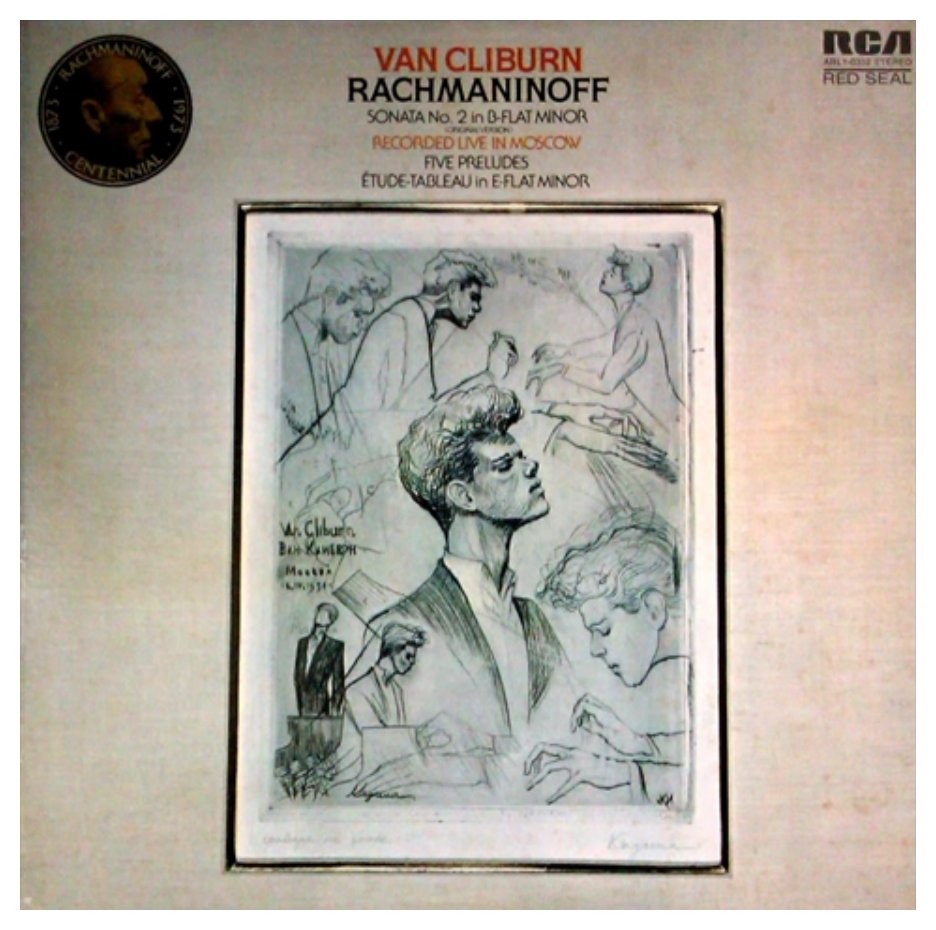

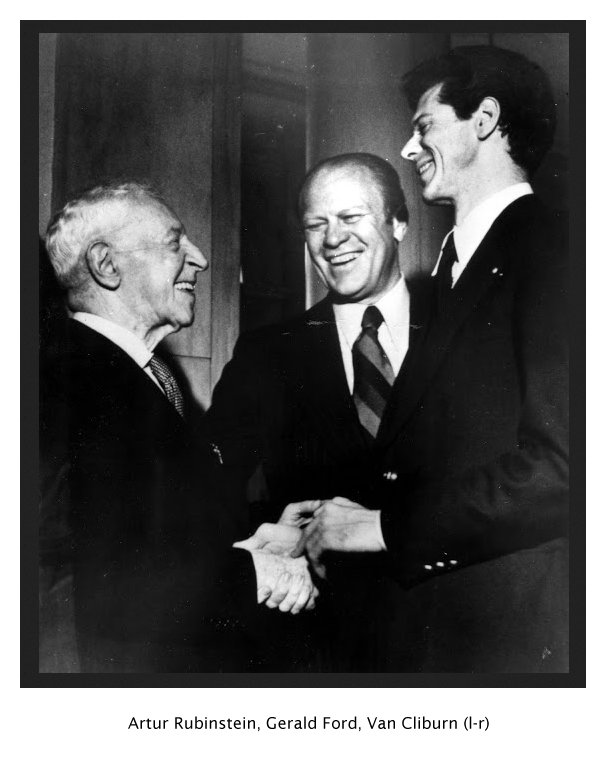

Following his triumph in Moscow, Mr. Cliburn played in several cities in the Soviet Union. From that time on, he toured widely and frequently with every important orchestra and conductor, in the most renowned international concert halls. Mr. Cliburn toured the Soviet Union many times between 1960 and 1972 for extended periods. He made numerous timeless and beloved recordings, including many major piano concerti and a wide variety of solo repertoire. Early in his career, a group of friends and admirers began the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition as a living legacy to Mr. Cliburn’s constant efforts to aid the development of young artists. The first competition was held in 1962. In 1987, at the invitation of President Ronald Reagan, Mr. Cliburn performed a formal recital in the East Room of the White House during the State Visit honoring Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s then general secretary [photo below]. Two years later, and thirty-one years after his triumph at the Tchaikovsky Competition, Mr. Cliburn returned to the Soviet Union to perform at the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory and in the Philharmonic Hall of Leningrad.

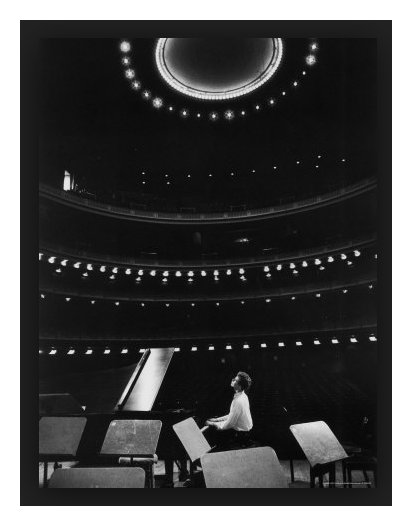

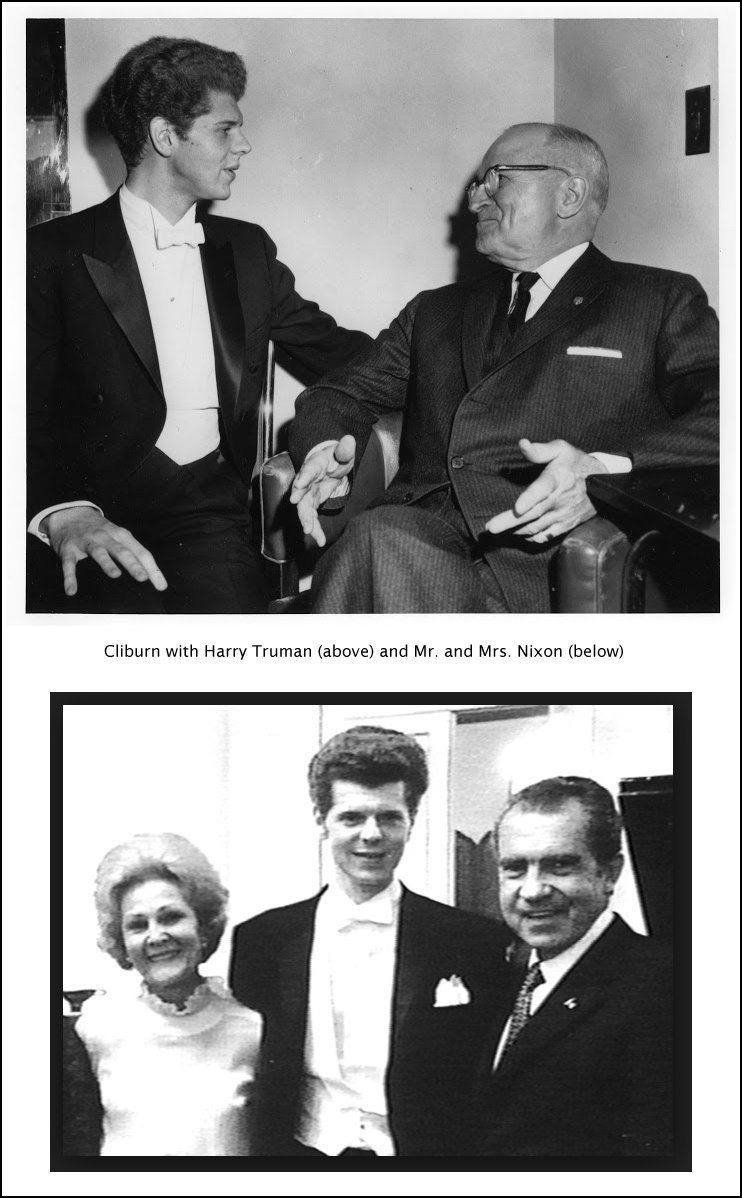

Carnegie Hall then requested that he play for its 100th anniversary season as soloist with the New York Philharmonic. Over the years, Mr. Cliburn has opened many U. S. concert halls, including the famous I. M. Pei Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas; the Lied Center for the Performing Arts in Lincoln, Nebraska; and the Bob Hope Cultural Center in Palm Springs, California. Mr. Cliburn was an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music in London. He received more than 20 honorary doctorate degrees. He provided scholarships at many schools, including Juilliard, the Cincinnati Conservatory, Texas Christian University, Louisiana State University, the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, the St. Petersburg Conservatory, and the Moscow Conservatory. Mr. Cliburn performed for every President of the United States since Harry Truman and for royalty and heads of state in Europe, Asia, and South America. He received Kennedy Center Honors and the Grammy® Lifetime Achievement Award. In a 2004 Kremlin ceremony he received the Order of Friendship from President Vladimir Putin, and in 2003, President George W. Bush bestowed upon him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. President Barack Obama honored Mr. Cliburn with the National Medal of Arts in a ceremony at the White House in 2011.

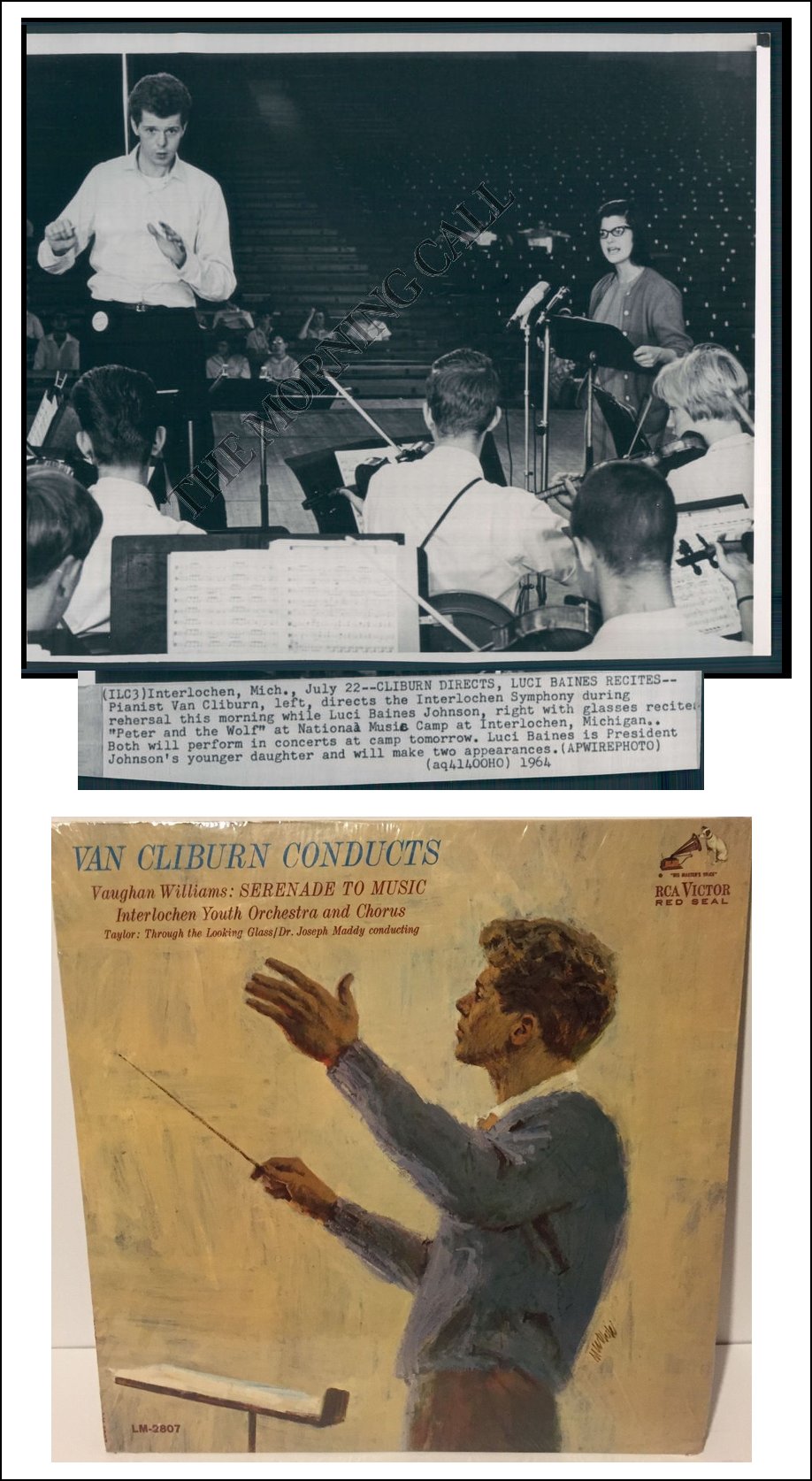

Here are a few of the highlights of his long and distinguished career . . . . . . . . .

-- Text from the Cliburn Website.

Photos from various sources.

|

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 16, 1994.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB four months later, and again in 1999.

This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that

time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.