|

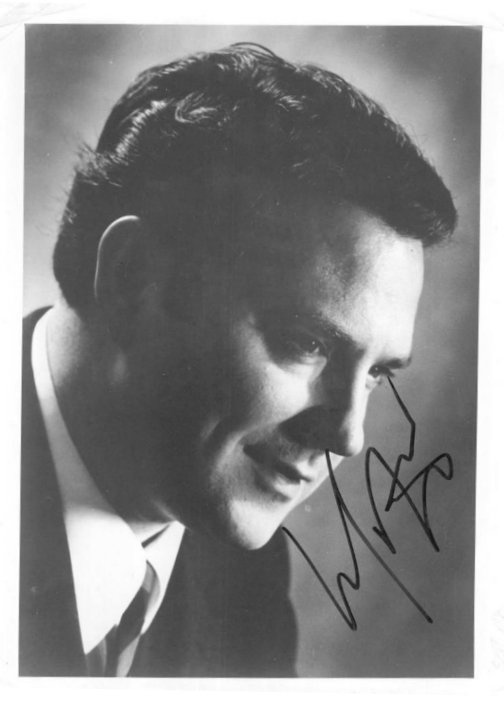

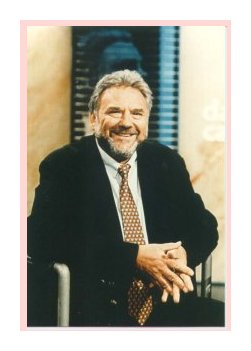

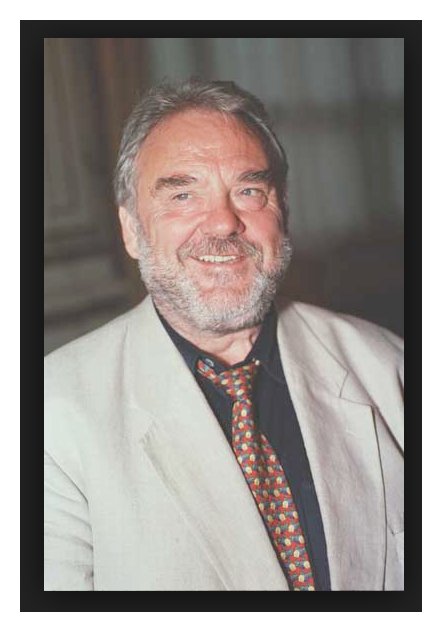

Hans Sotin

Born: September 10, 1939 - Dortmund, Germany He was a student of F.W. Hetzel and then of Dieter Jacob at the Dortmund Hochschule für Musik. In 1962 Hans Sotin made his operatic debut as the Police Commissioner in Der Rosenkavalier in Essen. After joining the Hamburg State Opera in 1964, he quickly became one of its principal members singing not only traditional roles by creating new roles in works by Blacher, Einem, Penderecki et al. His success led to his being made a Hamburg Kammersänger. In 1970 he made his appearance at the Glyndebourne Festival as Sarastro. He made his debut at the Chicago Lyric Opera as Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlos in 1971. That same year he sang for the first time at the Bayreuth Festival as the Landgrave where he subsequently returned with success in later years. In October 1972 he made his Metropolitan Opera debut in New York as Sarastro. From 1973 he sang at the Vienna State Opera. He made his debut at London’s Covent Garden as Hunding in 1974. In 1976 he sang for the first time at Milan’s La Scala as Baron Ochs. Hans Sotin also appeared as a soloist with the leading European orchestras. In addition to his varied operatic repertoire, Sotin has won distinction for his concert repertoire, most particularly of the music of J.S. Bach, Haydn, L.v. Beethoven, and Gustav Mahler. |

HS: [Smiles] It's a Roman style much more

than a German style. That was his idea, and I don't like it. It

looks good, but I don't like it.

HS: [Smiles] It's a Roman style much more

than a German style. That was his idea, and I don't like it. It

looks good, but I don't like it.|

Hans Sotin at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1971 - Don Carlo (Grand Inquisitor) with Lorengar, Cossutta, Cossotto, Milnes, Ghiaurov, Estes; Bartoletti, Mansouri Das Rheingold (Fafner) with Hofmann, Neidlinger, Holm, Hoffman; Leitner, Lehmann 1973 - Der Rosenkavalier (Baron Ochs) with Ludwig/Dernesch, Berthold, Blegen, Merighi, Zilio, Andreolli; Leitner, Schneider-Siemssen (Sets) 1979 - Tristan und Isolde (Marke) with Knie, Vickers, Dunn, Nimsgern, Versalle; Decker, Poettgen, Oswald 1980 - Boris Godunov [Opening Night] (Pimen) with Ghirurov, Baldani, Ochman, Trussel, Chookasian, Tyl, Gordon; Bartoletti, Everding, Lee, Hall Lohengrin (Henry) with Johns, Marton, Martin, Roar, Monk; Janowski, Oswald (Sets & Direction) 1982 - Tristan und Isolde (Marke) with Martin, Vickers, Denize, Nimsgern, Kunde, Negrini; Leitner, Poettgen, Oswald 1983 - Flying Dutchman (Daland [shared with Moll]) with Nimsgern, Carson, Schunk [Eric & Steersman]; Perick, Ponnelle 1986-87 - Parsifal (Gurnemanz) with Vickers, Troyanos, Nimsgern, Becht, Salminen/Kennedy, Kaasch; Perick, Pizzi, Tallchief Hans

Sotin with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

[Note: Rheingold and Fidelio were also performed at Carnegie Hall, and both Beethoven works were also recorded] 1971 - Das Rheingold (Fafner) with Ward, Kühne, Stolze, Dunn, Watts, Talvela, Lanigan, Paul, Altman; Solti 1979 - Fidelio (Rocco) with Behrens, Hofmann, Adam, Ghazarian, Kuebler, Howell; Solti [Interestingly, the previous year Sotin

had performed and recorded (both audio and video) the role of Pizarro with

Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic, and Janowitz, Kollo, Popp, Dallapozza,

Jungwirth, and Fischer-Dieskau.]

1986 - Beethoven Ninth Symphony [Opening Night] with Norman, Runkel, Schunk; Solti |

BD: Would you do Boris in German?

BD: Would you do Boris in German?

HS: It was a natural step for me. I was younger

when I sang the giant, Fafner. My voice was growing up to the high.

I think it is good when you sing Wotan with a darker register or color, and

not the more high timbre baritone.

HS: It was a natural step for me. I was younger

when I sang the giant, Fafner. My voice was growing up to the high.

I think it is good when you sing Wotan with a darker register or color, and

not the more high timbre baritone.

This interview was recorded in the studios of WNIB, Chicago, on October

25, 1980. Portions were used on WNIB (along with recordings)

in 1989, 1994, 1997 and 1999. A transcript was made and published

in Wagner News in July of 1981,

and in Opera Scene Magazine in October

of 1982. The transcript was re-edited and posted on this website in

2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.