[Note: This interview first appeared in Wagner News in May of 1988.

Most of the conversation was published there, but for this website

presentation, the portions which were omitted have been restored, and

the entire chat has been slightly re-edited. Photos and links

have also been added here.]

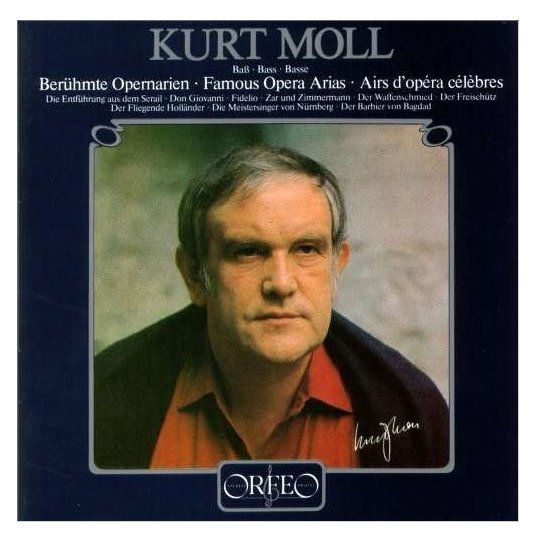

CELEBRATING THE 50th BIRTHDAY OF KURT MOLL

By Bruce Duffie

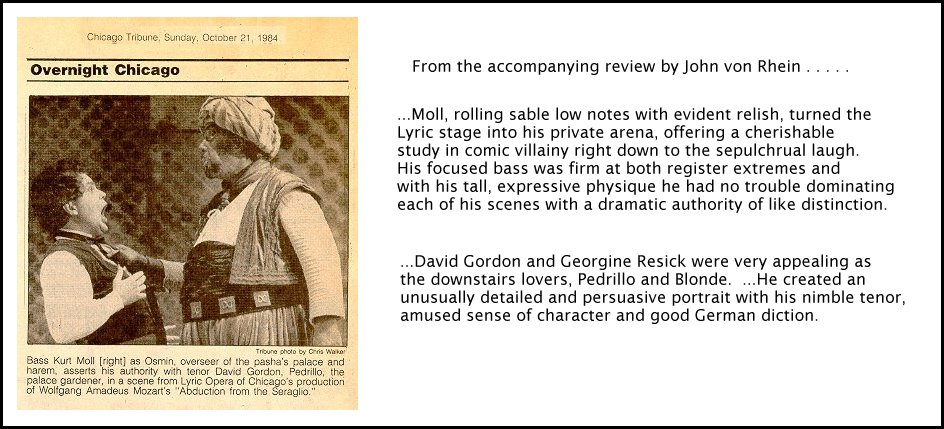

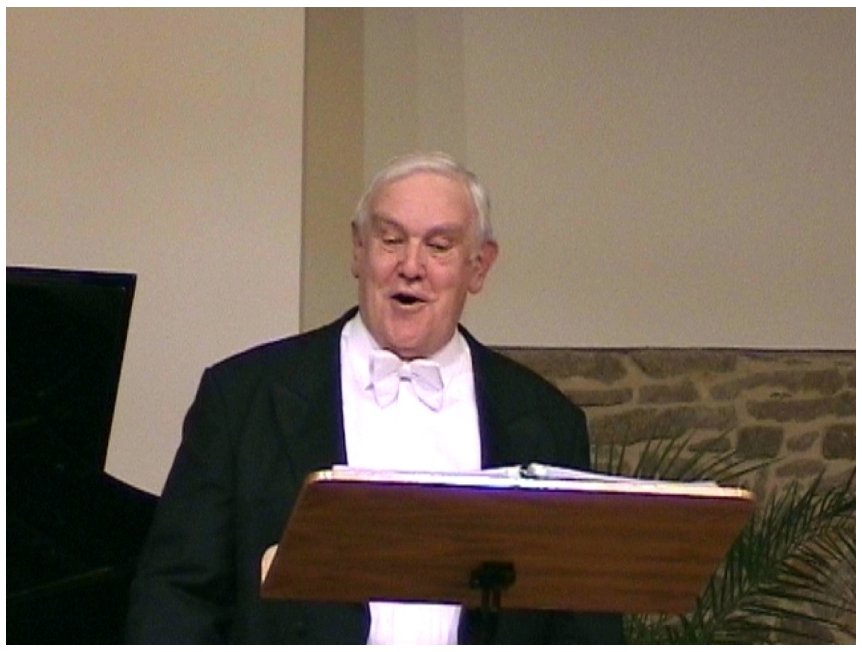

Most of the interviews that I have the privilege of

doing are fun, but some are very special for one reason or

another. Besides simply meeting this fine artist, the chat with

Kurt Moll was particularly memorable because of the translator

– David

Gordon. Readers of this journal will remember the

conversation

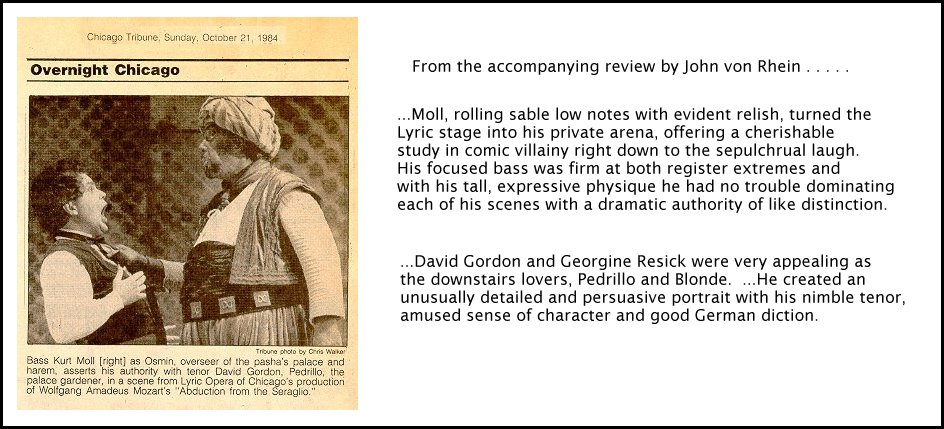

with him published back in May of 1982. When I met Moll in 1984,

he was in Chicago appearing as Osmin in Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem

Serail. The conductor was Ferdinand Leitner,

and the Pedrillo was none other than my friend, David

Gordon. So when Moll accepted my invitation for the interview and

indicated that while he would speak some English, it would be necessary

to have a translator, David immediately agreed to be there.

The speaking voice of Herr Moll is dark and rich and

deep, and I hope that some readers heard portions of the conversation

which were broadcast on WNIB on Easter of this year when we played his

recording of Parsifal to

celebrate not only the 50th birthday of the

bass, but also the 80th birthday of Herbert von Karajan. Besides

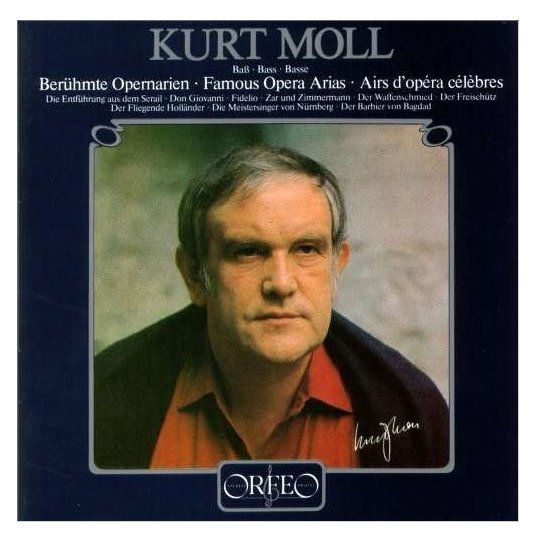

this last Wagner opus, Kurt Moll has sung and recorded all the great

bass parts with many of the world’s leading conductors. Among his

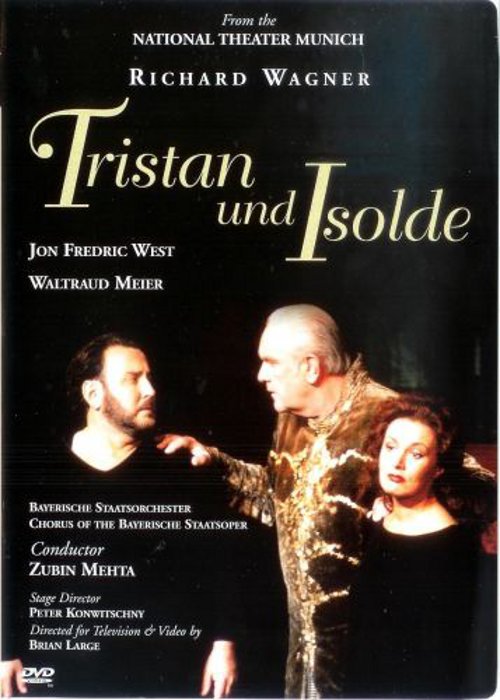

discography are Die Feen (!) (Sawallisch); Dutchman (Karajan);

Meistersinger (Solti); Tannhäuser (Haitink); Tristan (Kleiber); and

Walküre (Janowski).

He has also recorded Mozart’s Entführung

(Böhm); Zauberflöte

(Davis), and other works; Stauss’ Rosenkavalier

(Karajan); Weber’s Freischütz

(Kubelik); and discs of sacred works and

Lieder. [Names with links in these paragraphs indicate my

interviews with these musicians.]

This famous and admired singer celebrated his 50th

birthday in mid-April, and as a tribute to that milestone, Wagner News

is pleased to publish this conversation with Kurt Moll. We spent

about an hour and a half together talking about mostly Wagner, and here

is what was said…

Bruce Duffie:

Let’s start right in with Wagner. You’ve sung

many performances all over the world, as well as in Bayreuth. Do

the acoustics there cause you to sing any differently than in

other theaters?

Kurt Moll: Basically, no. It

doesn’t change the way that

you have to sing on the stage in Bayreuth. Although there is a

completely different acoustical feeling because the whole sound of the

orchestra comes first to the stage where it is mixed with the voice and

then goes out into auditorium where the public hears both sounds

together. This is dangerous because you hear so much orchestra

onstage that you tend to over-sing. If you know how much you must

give, it’s OK, but the first time is always strange. For the

conductors it’s very difficult because they must always be quicker than

normal in beating. But the acoustics in Bayreuth are phenomenal.

Kurt Moll: Basically, no. It

doesn’t change the way that

you have to sing on the stage in Bayreuth. Although there is a

completely different acoustical feeling because the whole sound of the

orchestra comes first to the stage where it is mixed with the voice and

then goes out into auditorium where the public hears both sounds

together. This is dangerous because you hear so much orchestra

onstage that you tend to over-sing. If you know how much you must

give, it’s OK, but the first time is always strange. For the

conductors it’s very difficult because they must always be quicker than

normal in beating. But the acoustics in Bayreuth are phenomenal.

BD: Are the

audiences in Bayreuth completely different from other cities?

KM: It’s different

because the audience consists mainly of people

who are Wagner specialists and they come from all over the world to

Bayreuth just to hear Wagner. It is a different audience from the

normal operatic audience. I know people who save all their money

all year and come to Bayreuth, and during the festival go to all 28

performances. The only place where only Wagner is played is

Bayreuth, and I don’t think they’ll ever play anything else there.

BD: Is there any

other composer who elicits such fanaticism?

KM: Apparently

not. The Salzburg Festival is allegedly a Mozart festival, but

they perform music of all different composers. The only place

where only Wagner is played is Bayreuth. I do not think they will

ever get the idea to play anything else there.

BD: Would it be

good to stage other operas either there, or in

another opera house of that design?

KM: Yes, I believe

so. The stage is very large, and it

would be very interesting to try music by another composer in that

space. They have tried to imitate the acoustic and build other

theaters like it, but have never succeeded.

BD: Do you read the

letters, etc., of composers whom you are singing?

KM: Sure, when I

first study the role I acquaint myself with the letters and so forth,

but when I perform the parts many times, with each new production I try

to find a new version, a new interpretation, a new way of looking at

each role. Sometimes with new stage directors and new conductors,

it is possible to see the role in a new light.

BD: Have the stage

directors today gone, perhaps, farther than Wagner would have wanted?

KM: Unfortunately,

yes. There is a whole lot of nonsense, especially with Wagner

while ignoring the enormous variety and complexity of the music and the

text. There is so much there that you really don’t

need to bring that much to it. You just need to perform the music

as it’s written and as the stage directions indicate.

It is truly gesamkunst, a

total art. The whole gestalt,

everything together – words, music, stage direction and

concept of the composer – is all so complex that you don’t

really need to bring much of yourself to it as a stage director.

You simply need to follow the directions that Wagner has left.

This is not to say that you have to look at these operas the way Wagner

looked at them through his own eyes in the Nineteenth Century. We

have new technical abilities involving stagecraft at our disposal and

we have new sensibilities which we should not ignore. But there

is a lot of foolishness done in the name of innovation.

BD: How much

alteration are we making, then, because we have lived another hundred

or more years?

KM: You must give

the audience members the opportunity to look at these operas through a

lens of the Twentieth Century. The art of interpretation, the

nature of interpretation has essentially changed during our

century. Today we see the works of Wagner as being

over-pathetic. Pathos is certainly written in, but today, in our

fast-paced life we look at these works differently from the time of

Wagner when people lived a slower and calmer existence. We should

honestly approach the pathos which Wagner intended without looking at

it through rose-colored glasses. We should look at the true

nature of Wagner’s music while not ignoring the Twentieth

Century’s sensibilities or stagecraft.

BD: Do these

characters that Wagner drew still speak to us today?

KM: I think so,

yes. Why not? In the book Wagner

Through the Eyes of a Jurist, it is funny. The writer

describes how many murders and robberies and other crimes are committed

in each opera, and he arrives at a figure of two hundred crimes which

would merit life in prison! [Laughter all around]

*

* *

* *

BD: Your voice

dictates that you sing these roles. Do you

like them, or do you have any latent desires to be a tenor?

KM: No, I don’t

want any other kind of voice. I’m very

happy with the voice that I have, and I’m very happy to be singing the

Wagner roles that I sing with a few exceptions. It’s not just the

voice, but a combination of the quality and your temperament.

BD: Let’s talk

about a few of these roles. You’ve

mentioned Gurnemanz. Is this the longest?

KM: This is the longest, and for me,

the most beautiful role, and

the one that I sing with the most pleasure. It’s a role in which

you find something new in every performance. You’re never done

with your development of the role. No matter how many times you

sing it, you never finish learning it. You always have to work on

it again and study it anew.

KM: This is the longest, and for me,

the most beautiful role, and

the one that I sing with the most pleasure. It’s a role in which

you find something new in every performance. You’re never done

with your development of the role. No matter how many times you

sing it, you never finish learning it. You always have to work on

it again and study it anew.

BD: I know this is

a dangerous question to ask, but is this your favorite role of all or

just your favorite Wagner?

KM: Just my

favorite Wagner. I am always engaged and involved with the one I

am doing at the moment. I also like Baron Ochs in Der

Rosenkavalier of Strauss and Osmin in Mozart’s Entführung. But

Gurnemanz is a special role because I identify somewhat with it

personally, with my temperament. I especially identity with him

in the third act.

BD: You feel old??

KM: Between Act

One and Act Three, Wagner states that he becomes three hundred years

older. It’s not a concrete literal aging, but a more figurative

and spiritual aging. The point of the 300 year gap is not

physical, but a matter of space and time, and most of all he is 300

years wiser. His character is transformed in

a transcendental way.

BD: Is Gurnemanz

completely overjoyed when Parsifal returns?

KM: I believe so,

yes. The difference in Gurnemanz between the

first and third acts is that in the first act, Parsifal has

to do something dramatic in order that Gurnemanz can recognize the

significance of Parsifal’s character. When he kills the swan,

Parsifal

demonstrates his guilt and feeling of pity and Gurnemanz recognizes

this. But by the third act, Gurnemanz has reached the

level of spiritual development that he would recognize Parsifal without

even actually seeing him. He would feel his presence. He

would be

so sensitive. This is what the 300 years of development

represents. The other difference is that while Gurnemanz

recognizes Parsifal in the first act, he doesn’t recognize

the significance of Parsifal’s character as being a Savior.

BD: Is Parsifal

not the first to have come into their midst and

create a stir?

KM: Parsifal is

not the first to have done such a thing, but he’s

a different type. He doesn’t know who his father is or where he’s

from. He doesn’t know anything of himself, but he feels that he’s

done something wrong and he feels some kind of pity or empathy with

another living creature. Gurnemanz sees all of this, but operates

during the whole first act without knowing the significance

of Parsifal’s character or really understanding who Parsifal is.

At the end of the act, when the alto sings the one line, he hears it

but is

still not sure. Something clicks in his mind, but he’s still

uncertain. I’ve experienced stage-directions where Gurnemanz

hears the voice and takes a few steps in Parsifal’s direction as though

he wanted to catch him, as though he had an intimation of who Parsifal

was.

BD: Then does

Gurnemanz simply wait three hundred years for Parsifal to return?

KM: I believe

so. At least one hundred and fifty years! [Much laughter

all around]

BD: Are

the intermissions at Bayreuth too long?

KM: No. It’s

exactly right because Bayreuth exists for the

audience to totally experience Wagner. So, when you have any act

that lasts maybe two hours, an intermission of an hour is not too

much. Remember, the public is there for no other purpose except

to hear this performance.

BD: OK, but from

the point of view of the singer, is that

interval too long?

KM: Yes.

When I do Gurnemanz, I have time to go to dinner

between the two acts that I sing.

BD: Is that like

doing two operas – having to come back and start

all over again for the third act?

KM: Yes. You

have to warm up again before the third act,

and the first act is so long that one is physically tired

already. Of that two hours, I spend an hour standing on the stage

with only a few phrases to sing, but I must be onstage.

BD: [With a sly

nudge] Do you get bored with it?

KM: Yes.

[Again, much laughter]

BD: If you were to

direct Parsifal, would you

ever think to have the same man do both Amfortas and Klingsor?

KM: No. They

are two different characters.

BD: Not two sides

of the same figure?

KM: You have to

look at the story rather than deal with some kind of philosophy.

Very often, a stage director’s philosophy will intrude on

the story that Wagner clearly sets forth. Klingsor has left

because he is searching for something that he has not found. He

really has wounded himself; in a sense he has emasculated

himself. Amfortas was wounded by Klingsor.

BD: One time at the

old Met, Hermann Uhde sang both roles in a single performance, thus

being his own worst enemy.

KM: [Ponders it a

moment, but is un-amused] Of course it is possible

that both parts could be sung by the

same singer, the same voice, but in the story these are two entirely

different figures. If you look at the premiere of Don Giovanni, the same singer sang

both Masetto and the Commendatore.

BD: Is it ever a

good idea to have the same singer do two parts in one opera

– perhaps a Norn and Gutrune?

KM: In the

ensemble, certainly it’s possible, but when you have leading

roles, it’s not a good idea. While you can

do them with the same voice, you should have two different

characters represented. For an Esquire and a Flower Maiden, that

is all right.

BD: Have you done

Monterone?

KM: Yes, and I have

done Sparafucile, but not in the same production.

BD: Would you do

them both if asked?

KM: No. They

are not onstage together, but the scene-change is so quick that it

would be virtually impossible to do it. The one scene ends with

Monterone and the next thing you know Sparafucile is there. There

isn’t time for one singer to do both. It might work in

an extremely small theater when they needed to save money...

*

* *

* *

BD: Are there any

Wagner roles you haven’t sung yet that you’d

like to?

KM: I’ve sung all

the Wagner roles except Hagen and I’m really

not interested in that one because it doesn’t seem to suit my nature

particularly well. You need a kind of a raw voice, one that’s

like a

knife. You need to almost yell more than sing. You must cry

out rather than sing in a bel canto

style.

BD: Is that the way

Wagner wrote it, or has it just come down to us that way today?

KM: It’s possible

that

we’ve come to the point today where Hagen is a role for someone who

really can’t sing other parts any more.

BD: Is it a

voice-killer?

KM: Yes, but there are certain

special voices that can stand the

punishment of this role. As a matter of fact, I was singing in a

production of the Ring in

Paris with Solti conducting, and we were

supposed to do all four operas, but the last two were dropped because

of difficulties with the stage-direction team. I was supposed to

sing Hagen, and despite the fact that they were dropped, I was paid

anyway, and I decided at that time that there was no way that I could

ever earn that much money again by not singing a part. [Laughter

all

around] I also find that Hagen is so rough on the voice that it

interferes with other parts of my career which I really enjoy, such as

Lieder recitals.

KM: Yes, but there are certain

special voices that can stand the

punishment of this role. As a matter of fact, I was singing in a

production of the Ring in

Paris with Solti conducting, and we were

supposed to do all four operas, but the last two were dropped because

of difficulties with the stage-direction team. I was supposed to

sing Hagen, and despite the fact that they were dropped, I was paid

anyway, and I decided at that time that there was no way that I could

ever earn that much money again by not singing a part. [Laughter

all

around] I also find that Hagen is so rough on the voice that it

interferes with other parts of my career which I really enjoy, such as

Lieder recitals.

BD: Tell me about

Hunding. Is he really a nasty fellow, or

just somebody who’s been betrayed?

KM: Hunding is not

just your everyday guy. He’s someone who

has gotten in over his head and has been betrayed. He’s gotten a

really raw deal. He’s not like Hagen. Hagen is, by his very

nature, an evil character. Hunding, on the other hand, is a

temperamental man. He is easily excited and quick to anger and

quick to violence. He’s not an evil person, but you can’t make

him into a nice guy. From his very first entrance, he finds

himself in a situation where he is provoked into evil action. He

is defending himself. He is provoked into this and becomes

evil. He is the man of the house. He is uncouth and he’s

kind

of a hooligan. He sees what’s going on, and he’s not

stupid. At the same time, he doesn’t react immediately. He

sees what Siegmund is doing, but he gives him some time to

explain. By saying that the fight will be tomorrow, he gives

Siegmund a chance to get out of the situation.

BD: Does Hunding

want Siegmund to escape?

KM: I cannot say

that, but he gives him the possibility to escape. A truly evil

man would demand the duel then

and there. He is a strong man. He tells Sieglinde to go to

the kitchen and work there. It is possible that Hunding wants to

avoid the

battle. He’s not a bad man, but the situation and circumstances

force him into unpleasant behavior.

BD: Is it a

grateful role to sing even though it is short?

KM: The role

itself is not a very long one and I like to sing it

very much. You can make a great deal out of it, although there

isn’t very much to sing. There is also the dramatic potential

that you have a lot of time to sit and listen and react to what others

say and

do. It is dramatically and theatrically, as well as vocally, a

very interesting

role.

BD: Is there any

way to successfully stage the end of the second

act?

KM: If you take

into account all the mystical aspects of Die Walküre, then it’s

not difficult to find this particular scene believable.

BD: Have you sung

one of the Giants?

KM: Yes, I’ve sung

both.

BD: Which one is

better?

KM: Fasolt is much

better to sing. It’s a very beautiful

role to sing, but Fafner is a much better role to make money with

because Fafner appears in two operas, and Fasolt only in one.

BD: Why is Fasolt a

more beautiful role to sing?

KM: He’s a more

simpatico fellow. He has a

heart. He is a nice fellow and must show during the entire opera

that he’s in love with Freia.

BD: Could he

actually have actually been happy if he could live with her?

KM: Yes of course,

if it hadn’t have been for his brother.

Fafner was the capitalist. He wants only the gold, and is capable

of murdering his own brother for it. The line is ironic – he

says, “The bigger half for me.” That is unrealistic, but he

would have gotten it!

BD: Would Fasolt

have been willing to take a smaller portion?

KM: Yes.

It’s all the same to Fasolt. He

feels here [gestures to his heart]. He looks for Freia as the

gold is piled up

and tries to see her through the tiniest hole, as though he doesn’t see

the gold. He only wants to see Freia. He is very sad when

he no longer sees Freia.

BD: So instead of

being concerned with the bargain and the amount

of gold, is he making sure his memory of Freia is gone completely?

KM: He doesn’t

care about the gold. He’s only concerned with the catching one

last glimpse of

Freia. In fact, it’s only when he hears Loge tell Wotan not to

worry about the gold as long as they keep the ring that he realizes

that it has do with anything materialistic. That’s the first

inkling that he has that this is more than the original bargain.

He literally lets the ring slip through his fingers. Fasolt has

no feeling for material things. He thinks with his

heart and Fafner thinks with his mind.

BD: Does Fasolt

have any home life, or is he looking to begin one with Freia?

KM: Maybe. I

don’t know.

BD: Is he a good

construction engineer:

KM: He

is an architect and

Fafner is the builder. Fafner, meanwhile, is totally obsessed

with the gold.

BD: Fasolt is the

brains and Fafner is the brawn.

KM: Yes!

BD: Ok, now from

the other side, is Fafner right in trying to get

all the gold?

KM: Yes. He

tries to get it all.

BD: So then why is

he later incapable of doing anything with it

except stand guard as a dragon?

KM: What else can

he do with the gold as a dragon – he can’t spend it. He can’t

do anything with it.

BD: So why does

Fafner turn into a dragon?

KM: It happens

during the interval between the operas, and Wagner

didn’t write down why. There is nothing to indicate this.

It’s not part of the tale of the

Niebelungen. Fasolt and Fafner are part of traditional North

German

mythology, the saga, but the dragon is just something that is suddenly

there in Wagner’s story. In Germany he’s

called “The

Wagner-Fafner”. Wagner just thought it

up.

BD: It seems like a

terrible waste. I always wonder why Fafner didn’t have

enough intelligence to do anything with the gold.

KM: I

did a

production once at La Scala where Fafner represented the figure of

Lenin, and I sat on a factory roof with about twenty or twenty-five

other Lennins

around me.

BD: I guess you

could call them Niebel-Lennins!

KM:

[Laughing] Fafner-lungen! When Siegfried came to slay me,

he took a red scarf

away from me, which represented the blood. Actually, you can

solve all this Fafner problem by doing it the way Wagner originally

wrote it. Fafner was to be sung from behind the scenes with a

megaphone, unseen by anyone. The megaphone created an unnatural

voice.

BD: Is it wrong to

actually see the person onstage?

KM: I think so, yes.

BD: Were you every

actually put inside the dragon onstage?

KM: No, I’ve never

actually functioned as a dragon onstage.

I’ve always been behind the scene except for that production where

instead of Fiddler on the Roof, I was Fafner on the Roof.

[Laughter]

BD: One last

question about the Ring – is

it one opera?

KM: What you

should do is what someone tried once. They used a large football

stadium and played all four operas together at the same time! But

it doesn’t work because Rheingold

is so much shorter than the others. [Laughter] Seriously, it

is not one opera, but one great single unified work.

You can’t play one opera alone because it is such a total musical

work. They all belong to each other

as a unit together.

*

* *

* *

BD: Let’s move on

to the Dutchman. Do you

like playing Daland?

KM: Oh yes.

BD: Is Daland a

smart

character?

KM: He’s very

naïve. He’s a typical seafaring man who

dreams constantly of some great material monetary windfall, and then

all of a sudden, he finds himself in a situation where it is laid at

his feet. He wants the

best for his daughter, and he has dreamed of this for so long.

BD: He has no

hesitation about handing over his daughter to this man just because he

has money?

KM: Just a little

bit, perhaps. He

is perhaps a little mistrustful of this Flying Dutchman, but he sees

the ability to have both – the wealth and the happiness for his

daughter. So he takes care of both of these things at once.

BD: Should the

opera be played in one piece or three?

KM: In one, I

think. The famous Ponnelle production which we did here in

Chicago last season

was very good because it was all played in a sort of mystical way like

a

fairy tale or Dickens. It brought out the magical qualities of

the opera, sort of unrealistic.

BD: Ponnelle made

it all the dream of the steersman. Is

this a good idea?

KM: No, I don’t

think it has to be a dream. The piece

itself is good as it stands. The Bayreuth production of Kupfer

makes it the

dream of Senta. Wagner was always so exact in his directions that

if he had

wanted it that way, he would have written, “This is the dream of the

Steersman” or “This is the dream of Senta,” but he didn't

write those things.

BD: Could it be

the dream of Daland?

KM: Maybe a stage

director will get that idea sometime. [Laughing] Why not?

BD: This is why I

asked earlier if stage directors have gone too far.

KM: Yes,

sure. Maybe too far. It’s very difficult to know

how far to go as a stage director. It’s always

possible to go as far as you can, artistically, and then take one step

too far. That makes the concept too much.

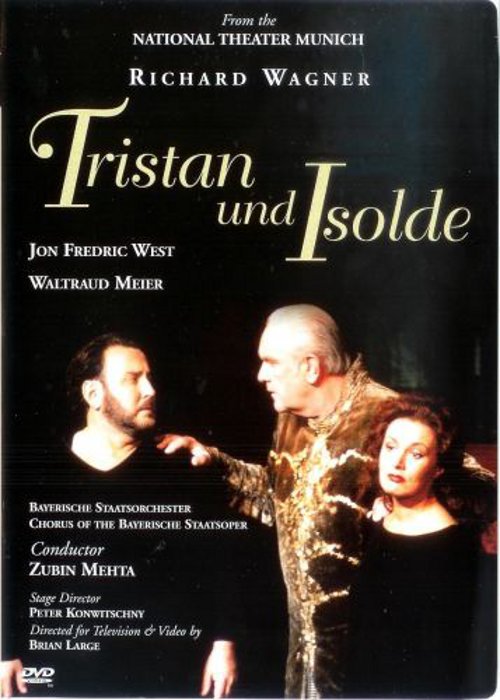

BD: What about

King Marke – is he a sympathetic character?

KM: You have to understand that not

looking at it from a musical standpoint, but in history he’s not

presented as

a very humane king. When you look at the operatic role, you must

see it through the music of Richard Wagner. The music is, for me,

the very intonation of humanity. Wagner makes King Marke much

more humane, and much more sympathetic than the general

history upon which Wagner drew for the opera. I’ll tell you of a

situation in Munich. The stage director wanted to

give me a bald head and a big mustache and a wolf-skin coat so that I

looked like Genghis Kahn. I came out for the first

orchestral rehearsal with this on and said, “I’m

sorry, I can’t do

this with me looking like that. I can’t sing it that

way.” I didn’t have voice at all. I

took off the mustache and the coat and the bald-head and

I just laid them on the prompter’s box and went back to the dressing

room. Within a few minutes the director came to me and said I

could look as

normal, and his entire concept was changed. My point is what

concept for Tristan could he

have had thought out so carefully and painstakingly if he could change

it in a matter

of two minutes?

KM: You have to understand that not

looking at it from a musical standpoint, but in history he’s not

presented as

a very humane king. When you look at the operatic role, you must

see it through the music of Richard Wagner. The music is, for me,

the very intonation of humanity. Wagner makes King Marke much

more humane, and much more sympathetic than the general

history upon which Wagner drew for the opera. I’ll tell you of a

situation in Munich. The stage director wanted to

give me a bald head and a big mustache and a wolf-skin coat so that I

looked like Genghis Kahn. I came out for the first

orchestral rehearsal with this on and said, “I’m

sorry, I can’t do

this with me looking like that. I can’t sing it that

way.” I didn’t have voice at all. I

took off the mustache and the coat and the bald-head and

I just laid them on the prompter’s box and went back to the dressing

room. Within a few minutes the director came to me and said I

could look as

normal, and his entire concept was changed. My point is what

concept for Tristan could he

have had thought out so carefully and painstakingly if he could change

it in a matter

of two minutes?

BD: Did he have

strange ideas for the other characters?

KM: No. He

didn’t have any kind of strange concept for the other

characters in the opera, only for King Marke because he

wanted to show that he knew some

of the history of King Marke and wanted to display that.

BD: Would King

Marke have been happy with Isolde if she had not

fallen in love with Tristan?

KM: In Wagner’s

representation of him, King Marke was remarkable

in that his heart was big enough that he could still love Isolde even

though she was, obviously to him, in love with Tristan. He could

accept this situation and live with it.

BD: So, is he

happy for them?

KM: No – “happy”

is not the right word. “Happy”

is something

else altogether. He is not unhappy. He is disappointed with

Tristan and forgives him. He understands.

BD: If Tristan had

not been wounded, it might have been a happy

ending?

KM: I think so,

perhaps.

BD: Could Tristan

and Isolde have been happy together?

KM: Not after the

first act, certainly not.

BD: Were they in

love anyway and the drink just pushed them toward it, or was it totally

the result of the potion?

KM: This is another

story that must be looked at in a more mystical and abstract way rather

than

a realistic and concrete representation of reality. The opera

represents a melding of their two souls. This is a very mystical

representation. In every Wagner opera,

there is some mystical aspect – even in Die Meistersinger.

BD: Do we try to

psychoanalyze Wagner too much?

KM: Yes, perhaps a

bit too much. By the same token, it’s

good to psychoanalyze Wagner because there are so many other pieces of

music that one cannot psychoanalyze at all.

BD: Is Die Meistersinger completely

different because the

characters are completely human?

KM: Yes, it’s

entirely different. It’s the only Wagner

opera where all the characters are just normal people taken out of

normal everyday life.

BD: Was Wagner

successful in writing about normal everyday people?

KM: Certainly.

BD: Your role is

Pogner, but do you ever want to sing Hans Sachs?

KM: Sure, but I

doubt that I ever will. The tessitura is

not right for the kind of voice that I have.

BD: Tell me about

Pogner. Do you like the man?

KM: No. I

like the role, but I don’t like the character

because he’s too quick. He doesn’t think about what he’s

saying. He makes a speech in the first act which begins

very poetically, about the beautiful festival. Then, in two

phrases at the end of the speech, he says he’ll give his own daughter

for the prize for the best singer.

BD: Doesn’t she

have any choice in the matter?

KM: No. She

has no possibility of any choice. He says

he will give her to the best singer. She can refuse, but if she

refuses, she can never marry anyone else.

BD: Is there any

connection between Pogner and Daland?

KM: Yes, there is

but Daland is more honest, I believe.

BD: This is too

bad... I always used to like Pogner! [Laughter all around]

KM: With Pogner,

everything is couched in this

“Biedermeier” or pompous bourgeoisie. He is not a likeable

character at all; he is not an honest character. He is the big

merchant, the big rich man. Everything is well-dressed and has a

good appearance and is pompous. There is toil and drudgery along

with a conceited, pompous

nature to him. Daland is only interested in the material side of

things because it’s to his advantage. Pogner wants material

things because it makes him look better in front of his peers.

BD: Doesn’t Pogner

care about Eva’s happiness?

KM: Pogner himself

doesn’t think about it. He makes a

decision in the first act and then in the second act he regrets

it. I think he would retract it if he could, but

he can’t. He expresses this clearly in the scene when he’s

walking with Eva towards Sachs’ house.

BD: Does Pogner

hope it will be Hans Sachs who wins the contest?

KM: No, I don’t

think so. He promised Beckmesser to put in

good words for him, and it’s possible that Pogner would be happy if

Beckmesser won. But by the same token it’s entirely possible

that he promised Sachs and maybe some other Meister the same

thing. We don’t know. In the finale, though, he thanks

Sachs. What else can he do?

BD: Is Pogner happy

in the end with how it turns out?

KM: Sure. He

has to appear to be happy

whether he is or not. We’re not sure, but he cannot show that he

is

unhappy with the outcome. He’s the type of guy who will put up a

front.

BD: Is there ever

any inkling of the relationship of Pogner and

his wife?

KM: There is no

mention in the opera of the wife, only the fact

that he is a widower. If he were married, he would surely bring

her to the festival scene.

David Gordon:

[Adding an observation of his own amongst the translating.

Remember, Gordan has sung the role of David in this opera.] I don’t

know about that. If Pogner would bring a wife, were they all

widowers? There’s not a single wife present among all

the Meisters. They’re all there without their wives.

KM: I doubt

that he would have made such a

crass decision about giving his daughter away if he had a wife.

BD: Does he need a

wife?

KM: He is too old

now.

BD: What kind of

decisions would the wife had made for Pogner?

KM: She would have

taken care of Eva.

David Gordon:

[Again an observation of his own] Another indication of this is

the presence of

Magdalena. She was probably a nanny hired to take care of things

when Pogner’s wife died.

KM: The wife

would have

probably also been a sort of go-between for Eva and Sachs when she

noticed there was an interest between them.

BD: Would she have

stopped it?

KM: Maybe.

But in any event, she never would have allowed the

father to say that tomorrow he was going to give the daughter away to

the highest bidder. She might have urged her husband to give a

very expensive gold watch to the winner as a gesture.

BD: Perhaps a date

with Eva?

KM: [Smiles, laughs

quietly, and ponders this a bit]

*

* *

* *

BD: What about

King Henry in Lohengrin? He seems to just

stand around and put in his two-cents worth every now and then.

KM: Henry is a character who is very

interesting because he

actually existed and you can view him. He was a real

person. He was the first king who built fortified castles in

Germany. Henry established provinces which were able to

defend themselves against vandals. These fortified castles gave

protection at night from roving bands of terrorists. He was a

good king and kind king. Wagner always used a lot of poetic

license in creating the characters such as Hans Sachs (who really

existed), but in the case of

Heinrich, he was very true to the actual figure. Tannhäuser or

Parsifal are examples of

historical situations into which Wagner put a

mystical figure.

KM: Henry is a character who is very

interesting because he

actually existed and you can view him. He was a real

person. He was the first king who built fortified castles in

Germany. Henry established provinces which were able to

defend themselves against vandals. These fortified castles gave

protection at night from roving bands of terrorists. He was a

good king and kind king. Wagner always used a lot of poetic

license in creating the characters such as Hans Sachs (who really

existed), but in the case of

Heinrich, he was very true to the actual figure. Tannhäuser or

Parsifal are examples of

historical situations into which Wagner put a

mystical figure.

BD: In the case of

Parsifal and Lohengrin, were they literal or spiritual father and son?

KM: It is a

spiritual relationship. It is all myth. There really was a

Tannhäuser, but Wagner

created the Venusberg. This is typical poetic license of

Wagner.

Perhaps the Venusberg scene was a daydream of Wagner himself.

BD: Do you think

that Wagner was writing a self-portrait in any

of these characters? Is Wagner Walther von Stoltzing or

Gurnemanz?

KM: Certainly not

Gurnemanz... perhaps Parsifal. That

opinion, however, is not shared by

many stage directors who let Wagner walk

onto the stage in the personage of Wotan or Hans Sachs. Maybe

Wagner thought about this, but you should do the piece the way Wagner

wrote it.

BD: Parsifal was written specifically

for the Bayreuth theater. Does it work in other opera houses?

KM: Sure.

BD: Wagner said the

piece was only to be performed at Bayreuth.

KM: I don’t

think he was that serious about it. He might have been thinking

materialistically of having a monopoly on the performance rights to the

work.

BD: Is there a

direct line from Wagner to Strauss?

KM: No. In

musical development, maybe, but Strauss is, in my opinion,

another book. Wagner, in his own mind, was always the poet and

musician together. Strauss usually

used another writer as librettist. The musical side is also

somewhat

different. In Strauss, it’s often a kind of dialogue, a

conversation, but in

Wagner it’s on a higher level where word and music become one thing

rather than the music expressing the words.

BD: For that

reason, are the Wagner operas are more unified, more

organic because he was his own librettist?

KM: Yes. The leitmotivs and things draw them

together.

BD: Would Wagner

work well in translation?

KM: I don’t

know. I think not.

BD: For instance,

we have a wonderful translation now by Andrew Porter of The Ring. [See my Interview with Andrew

Porter.]

KM: Probably

English is the best language to translate German

into. I don’t think it works as well in Italian or other Romance

languages. The flow of the language, the similarity between

English and German is very close, and that allows the sounds to be

translated easily from one to the other, but the similarity is not

there between German and other languages. I heard Lohengrin in

Italian and it sounded very good, but it was something entirely

different. It was a different piece.

David Gordon: I

heard a recording of Parsifal

in Japanese when I was in Japan. [Laughter]

BD: Wagner speaks

to the whole world.

KM: I believe you must

not have

to have a translation into another language to understand him because

he puts so

many helpful things into the music to help you understand the message

he is

trying to convey. If you spend a little time learning the musical

language, then you understand what he’s trying to say, and you don’t

necessarily need to understand every word of the German language.

I think that Wagner is, in a sense, computer music. If he’d

had a computer in his time, he absolutely would have used it to help

him write his operas. He would have put all the different

combinations of leitmotivs

into the computer in order to figure out ways to use them together and

to combine them.

BD: But the leitmotives are always changing as

the characters develop.

KM: He turns two motives into one and they

develop. He would use it as a pallette.

BD: Some people

would say the computer is too exact and is a tool which has no heart

and would take the soul out of the music.

KM: A painter who

goes to the store and buys the best paint in the world has the same

opportunity to paint just as good a picture as one who takes hours and

days to make his own paints from scratch. Maybe “computer”

is too limiting a word, but if he had some mechanism like a computer,

he certainly would have. Maybe he might have been

able to write ten more operas!

BD: Would Wagner have

also jumped at the chance to use television and recording techniques?

KM: Sure. It’s

difficult to say. He was very enthusiastic about all

sorts of new developments in stagecraft and stage technology. For

example, he used the apparatus which made the Rheinmaidens appear to be

swimming.

BD: Thank you for coming

to Chicago again. It’s been wonderful to speak with

you. Will you return to Lyric Opera?

KM: Yes. I don’t

exactly know yet, but I will come. After this I go to New York

for a recital in Carnegie Hall of Schubert, Brahms, Schumann and

Loewe.

BD: When you sing a

recital, do you have to tune your voice down a bit?

KM: Yes, but it’s

very good for the voice.

BD: Is it good for

the voice to balance your career with some Wagner and other operas and

some recitals?

KM: For me it’s

good. [And with that we said our good-byes.]

*

* *

* *

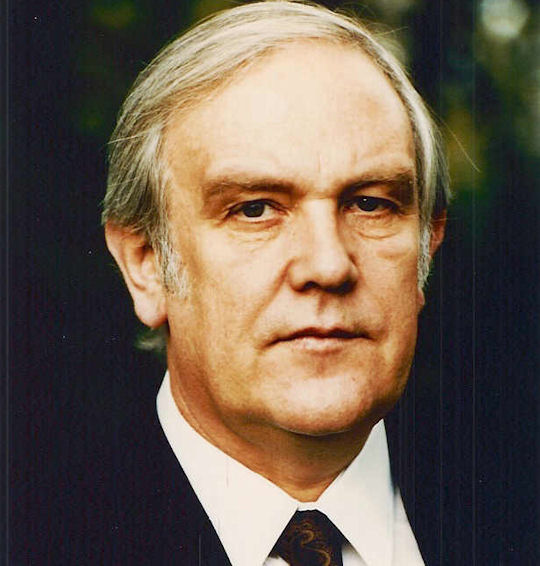

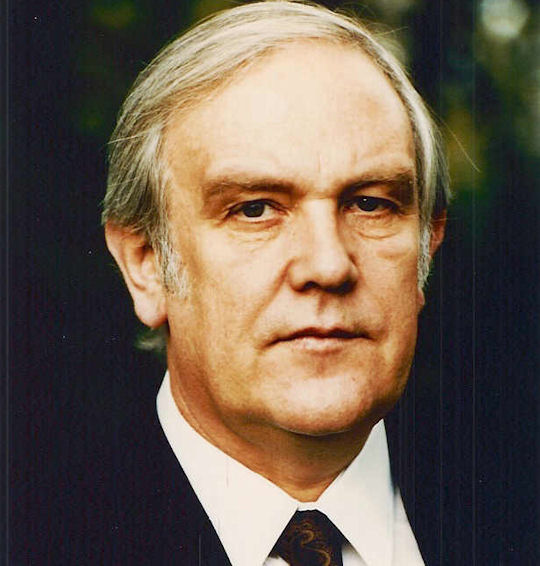

My special thanks go to David Gordon, the splendid lyric tenor who

translated for us during the conversation. For several years an

artist with the opera in Linz, Gordon did his first Wagner part there

in 1977 – the second nobleman of Brabant in Lohengrin, singing a total

of 27 performances. He has also performed David in Meistersinger

in San Francisco under Kurt Herbert Adler, with Karl Ridderbusch as

Sachs, and sang Mime in Rheingold

there in 1983, repeating the role in

Washington, D.C. Other operatic appearances in Chicago and the

world include Beppe in Pagliacci

(with Vickers as Canio) and the

Philistine Man in Handel’s Samson

(again with Vickers) – a role he has

sung at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. [See my Interview with Jon

Vickers.] In great demand in

oratorio, he has also performed major parts in Bach works with Karl

Richter, and is a specialist in contemporary music.

*

* *

* *

Bruce Duffie is a regular contributor to Wagner News, as well as the

semi-annual Journal of the Massenet

Society. He can be heard on

WNIB in Chicago, as well as on the Classical Collections program aboard

United Airlines. Coming this summer in these pages, a chat with

Christopher Keene, conductor of the Ring

at Artpark. [To read that interview, click here.]

=====

===== =====

===== =====

===== =====

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

-- -- -- -- --

===== =====

===== =====

===== ===== =====

© 1984 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his hotel on October 22,

1984. He spoke in both English and German, and portions were

translated by David Gordon. Segments were used (with recordings)

on WNIB in 1988, 1993, 1997 and 1998. It was transcribed and

published in Wagner News in

May, 1988. The

transcription was slightly re-edited and posted on this

website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago

from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

Kurt Moll: Basically, no. It

doesn’t change the way that

you have to sing on the stage in Bayreuth. Although there is a

completely different acoustical feeling because the whole sound of the

orchestra comes first to the stage where it is mixed with the voice and

then goes out into auditorium where the public hears both sounds

together. This is dangerous because you hear so much orchestra

onstage that you tend to over-sing. If you know how much you must

give, it’s OK, but the first time is always strange. For the

conductors it’s very difficult because they must always be quicker than

normal in beating. But the acoustics in Bayreuth are phenomenal.

Kurt Moll: Basically, no. It

doesn’t change the way that

you have to sing on the stage in Bayreuth. Although there is a

completely different acoustical feeling because the whole sound of the

orchestra comes first to the stage where it is mixed with the voice and

then goes out into auditorium where the public hears both sounds

together. This is dangerous because you hear so much orchestra

onstage that you tend to over-sing. If you know how much you must

give, it’s OK, but the first time is always strange. For the

conductors it’s very difficult because they must always be quicker than

normal in beating. But the acoustics in Bayreuth are phenomenal. KM: This is the longest, and for me,

the most beautiful role, and

the one that I sing with the most pleasure. It’s a role in which

you find something new in every performance. You’re never done

with your development of the role. No matter how many times you

sing it, you never finish learning it. You always have to work on

it again and study it anew.

KM: This is the longest, and for me,

the most beautiful role, and

the one that I sing with the most pleasure. It’s a role in which

you find something new in every performance. You’re never done

with your development of the role. No matter how many times you

sing it, you never finish learning it. You always have to work on

it again and study it anew.  KM: Yes, but there are certain

special voices that can stand the

punishment of this role. As a matter of fact, I was singing in a

production of the Ring in

Paris with Solti conducting, and we were

supposed to do all four operas, but the last two were dropped because

of difficulties with the stage-direction team. I was supposed to

sing Hagen, and despite the fact that they were dropped, I was paid

anyway, and I decided at that time that there was no way that I could

ever earn that much money again by not singing a part. [Laughter

all

around] I also find that Hagen is so rough on the voice that it

interferes with other parts of my career which I really enjoy, such as

Lieder recitals.

KM: Yes, but there are certain

special voices that can stand the

punishment of this role. As a matter of fact, I was singing in a

production of the Ring in

Paris with Solti conducting, and we were

supposed to do all four operas, but the last two were dropped because

of difficulties with the stage-direction team. I was supposed to

sing Hagen, and despite the fact that they were dropped, I was paid

anyway, and I decided at that time that there was no way that I could

ever earn that much money again by not singing a part. [Laughter

all

around] I also find that Hagen is so rough on the voice that it

interferes with other parts of my career which I really enjoy, such as

Lieder recitals. KM: You have to understand that not

looking at it from a musical standpoint, but in history he’s not

presented as

a very humane king. When you look at the operatic role, you must

see it through the music of Richard Wagner. The music is, for me,

the very intonation of humanity. Wagner makes King Marke much

more humane, and much more sympathetic than the general

history upon which Wagner drew for the opera. I’ll tell you of a

situation in Munich. The stage director wanted to

give me a bald head and a big mustache and a wolf-skin coat so that I

looked like Genghis Kahn. I came out for the first

orchestral rehearsal with this on and said, “I’m

sorry, I can’t do

this with me looking like that. I can’t sing it that

way.” I didn’t have voice at all. I

took off the mustache and the coat and the bald-head and

I just laid them on the prompter’s box and went back to the dressing

room. Within a few minutes the director came to me and said I

could look as

normal, and his entire concept was changed. My point is what

concept for Tristan could he

have had thought out so carefully and painstakingly if he could change

it in a matter

of two minutes?

KM: You have to understand that not

looking at it from a musical standpoint, but in history he’s not

presented as

a very humane king. When you look at the operatic role, you must

see it through the music of Richard Wagner. The music is, for me,

the very intonation of humanity. Wagner makes King Marke much

more humane, and much more sympathetic than the general

history upon which Wagner drew for the opera. I’ll tell you of a

situation in Munich. The stage director wanted to

give me a bald head and a big mustache and a wolf-skin coat so that I

looked like Genghis Kahn. I came out for the first

orchestral rehearsal with this on and said, “I’m

sorry, I can’t do

this with me looking like that. I can’t sing it that

way.” I didn’t have voice at all. I

took off the mustache and the coat and the bald-head and

I just laid them on the prompter’s box and went back to the dressing

room. Within a few minutes the director came to me and said I

could look as

normal, and his entire concept was changed. My point is what

concept for Tristan could he

have had thought out so carefully and painstakingly if he could change

it in a matter

of two minutes?  KM: Henry is a character who is very

interesting because he

actually existed and you can view him. He was a real

person. He was the first king who built fortified castles in

Germany. Henry established provinces which were able to

defend themselves against vandals. These fortified castles gave

protection at night from roving bands of terrorists. He was a

good king and kind king. Wagner always used a lot of poetic

license in creating the characters such as Hans Sachs (who really

existed), but in the case of

Heinrich, he was very true to the actual figure. Tannhäuser or

Parsifal are examples of

historical situations into which Wagner put a

mystical figure.

KM: Henry is a character who is very

interesting because he

actually existed and you can view him. He was a real

person. He was the first king who built fortified castles in

Germany. Henry established provinces which were able to

defend themselves against vandals. These fortified castles gave

protection at night from roving bands of terrorists. He was a

good king and kind king. Wagner always used a lot of poetic

license in creating the characters such as Hans Sachs (who really

existed), but in the case of

Heinrich, he was very true to the actual figure. Tannhäuser or

Parsifal are examples of

historical situations into which Wagner put a

mystical figure.