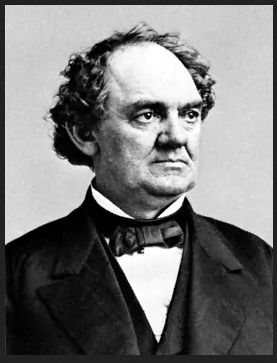

P.T. Barnum, in full Phineas Taylor Barnum,

(born July 5, 1810, Bethel, Connecticut, U.S.—died April 7, 1891, Bridgeport,

Connecticut), American showman who employed sensational forms of presentation

and publicity to popularize such amusements as the public museum, the musical

concert, and the three-ring circus. In partnership

with James A. Bailey, he made the American circus a popular and gigantic

spectacle, the so-called Greatest Show on Earth.

P.T. Barnum, in full Phineas Taylor Barnum,

(born July 5, 1810, Bethel, Connecticut, U.S.—died April 7, 1891, Bridgeport,

Connecticut), American showman who employed sensational forms of presentation

and publicity to popularize such amusements as the public museum, the musical

concert, and the three-ring circus. In partnership

with James A. Bailey, he made the American circus a popular and gigantic

spectacle, the so-called Greatest Show on Earth.

Playing upon the public’s interest in the unusual and bizarre (part of the “human curiosities” movement of the 19th century that saw the exploitation of African slave Sarah Baartman and the rise of carnival freak shows), Barnum scoured the world for curiosities, living or dead, genuine or fake. By means of outrageous stunts, repetitive advertising, and exaggerated publicity, Barnum excited international attention and made his showcase of wonders a landmark. Eager to change his image from promoter of human curiosities to impresario of artistic attractions, Barnum risked his entire fortune by importing Jenny Lind, a Swedish soprano whom he had never seen or heard and who was almost unknown in the United States. Dubbing Lind “The Swedish Nightingale,” Barnum mounted the most massive publicity campaign he had ever attempted. Lind’s opening night in New York City, before a capacity audience of 5,000, and her nine months of concerts across the United States earned immense sums. The Times of London echoed the world press in its final tribute: “He created the métier of showman on a grandiose scale.…He early realized that essential feature of a modern democracy, its readiness to be led to what will amuse and instruct it.…His name is a proverb already, and a proverb it will continue.” |

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 31, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB five days later. Permission was also granted to Carl Ratner for use in the dissertation Chicago Opera Theater: Sandard Bearer for American Opera 1976-2001. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.