|

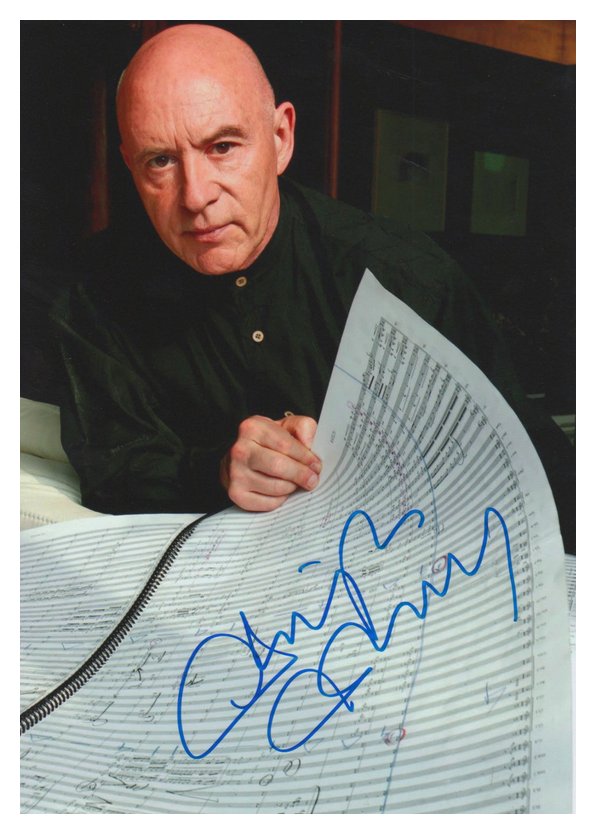

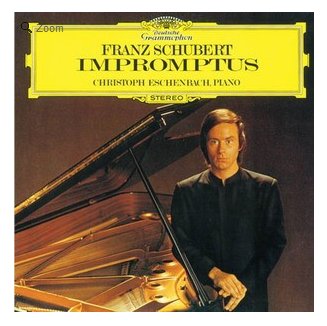

Christoph Eschenbach (Piano, Conductor)

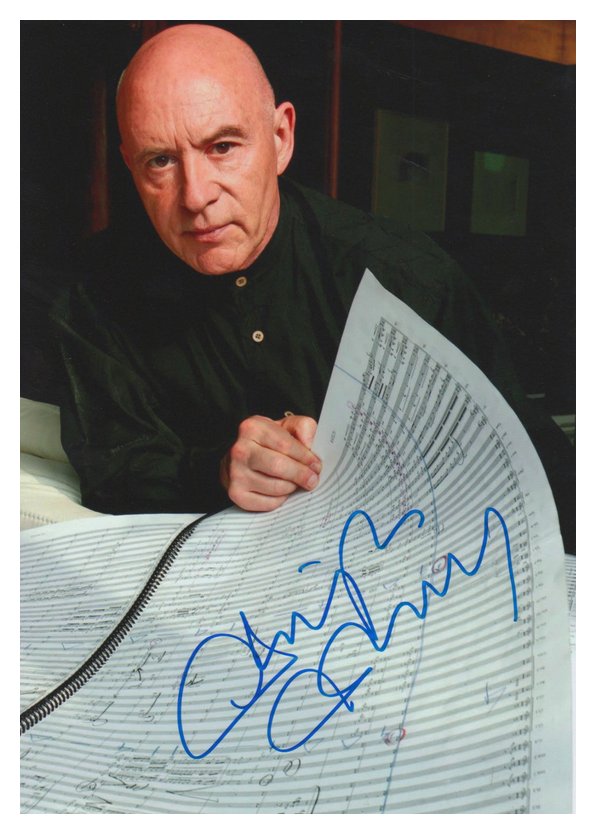

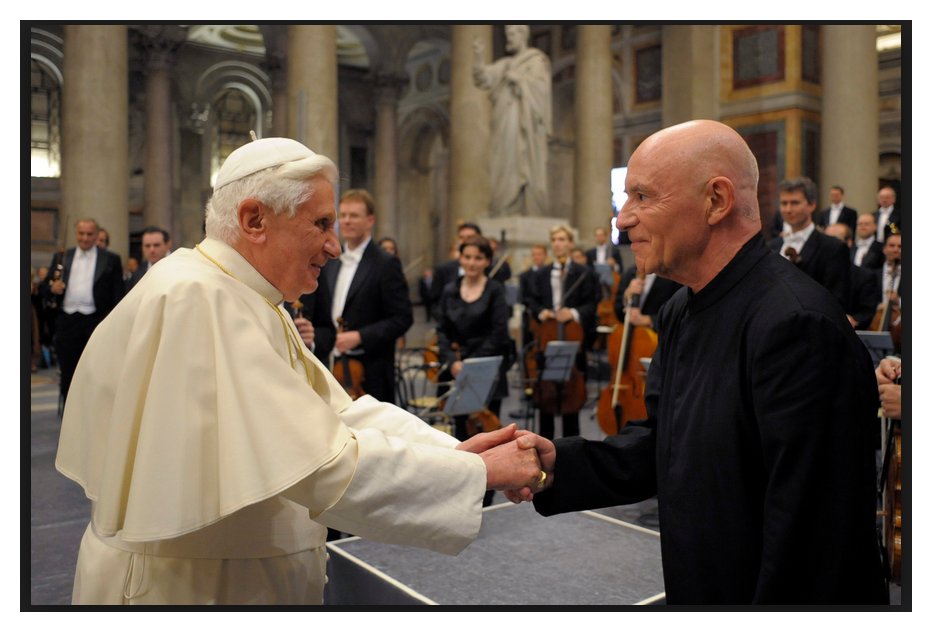

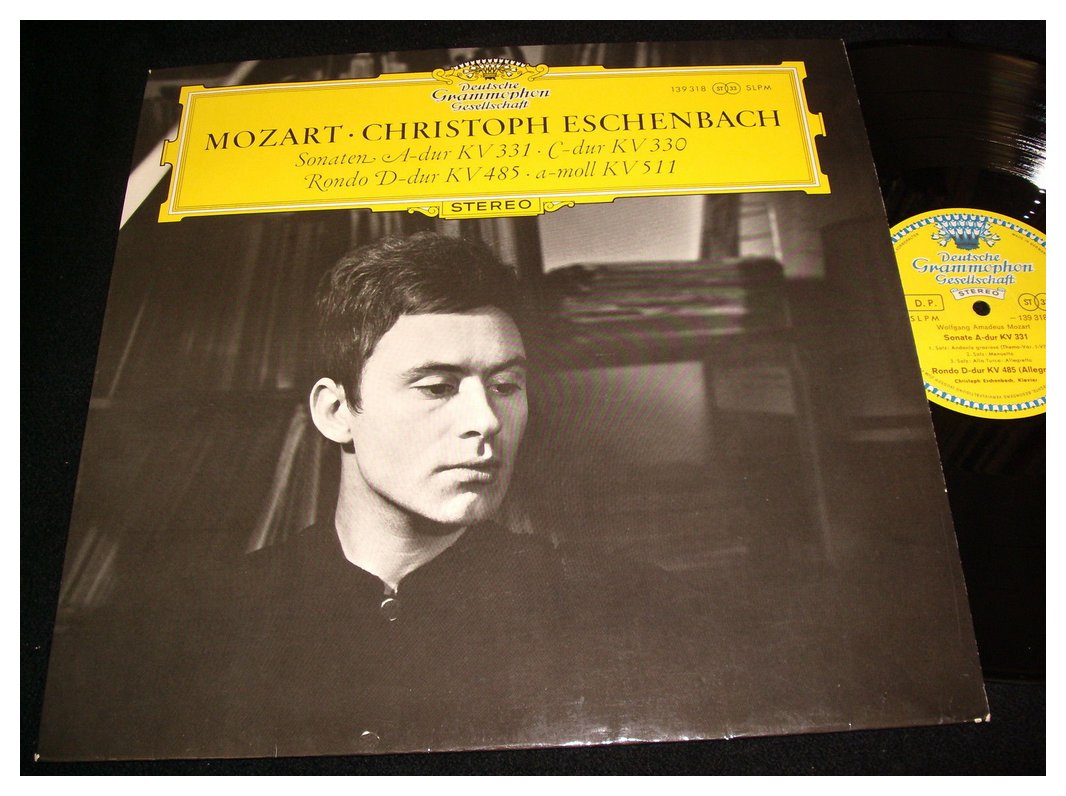

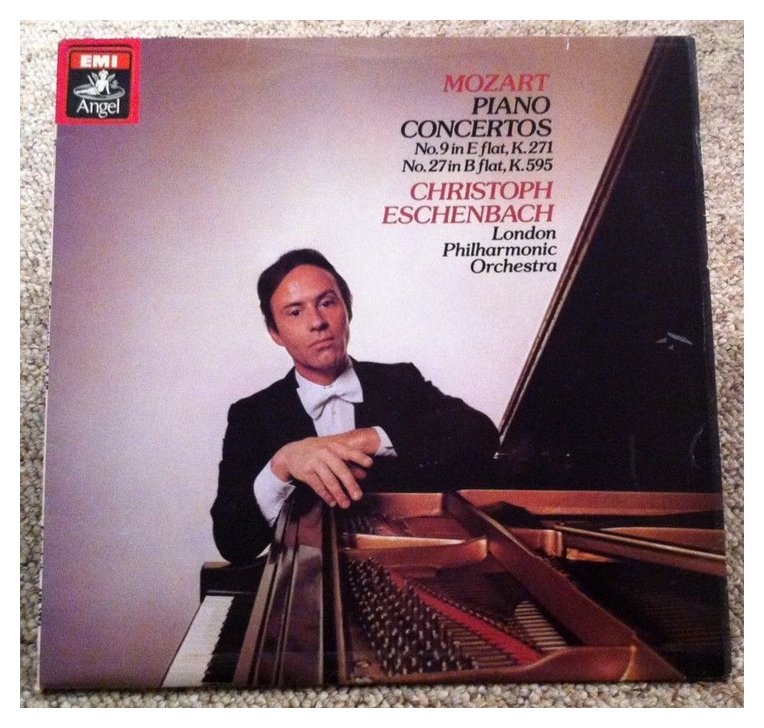

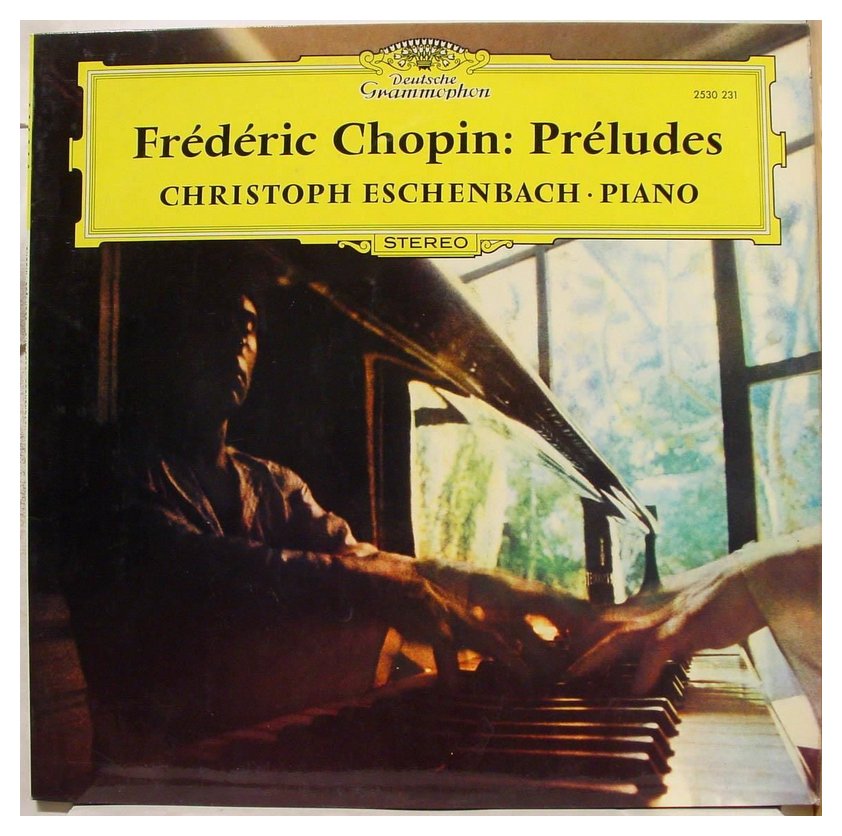

Born: February 20, 1940 - Breslau, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland) Christoph Eschenbach (real name Ringmann) is a German pianist and conductor. His parents were Margarethe (née Jaross) and the musicologist Heribert Ringmann. He was orphaned during World War II. His mother died giving birth to him; his father was sent to the war front to be slaughtered in a Nazi punishment battalion. His adoptive grandmother was then killed while trying to extract him and herself from the path of the Allied armies. As a result of the trauma, he did not speak for a year, until he was asked if he wanted to play music. Fortunately for the young boy, his mother's cousin, Wallydore Eschenbach (née Jaross), tracked him down after the war (1946) and adopted him from the refugee camp that would likely have claimed his life. It is from her side of the family that he eventually took his better-known surname. Eschenbach began studying piano at the age of eight, taught by his adoptive mother. She quickly realized his talents and enrolled him in the Hamburg Hochschule für Musik, where he studied both piano and conducting. At age 11 he witnessed Wilhelm Furtwängler conduct, which had a great impact on him. He later studied piano with Eliza Hansen in Hamburg. As a boy he won First Prize in the 1952 Steinway Piano Competition. In 1955 he enrolled at the Musikhochschule in Cologne, studying with Hans-Otto Schmidt-Neuhaus, and in 1959, he started studying conducting with Wilhelm Brückner-Rüggeberg. In 1962 he took second prize in the Munich International competition. However, it was with his first prize at the Clara Haskil Competition in Montreux, France, in 1965, that he finally made his mark. This new notoriety led to a London concert debut in 1966, and a prestigious debut with the Cleveland Orchestra and George Szell in 1969. Szell was impressed with his musicianship and gave him lessons in conducting, starting a close relationship that lasted until Szell's death in 1970.  He was soon essaying a wide repertory in concert tours throughout Europe

and America. Notable in his programs were a large number of works from 20th

century composers, such as Béla Bartók, Henze, Rihm, Reimann, Blacher, and

Ruzicka. His performances of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert were considered

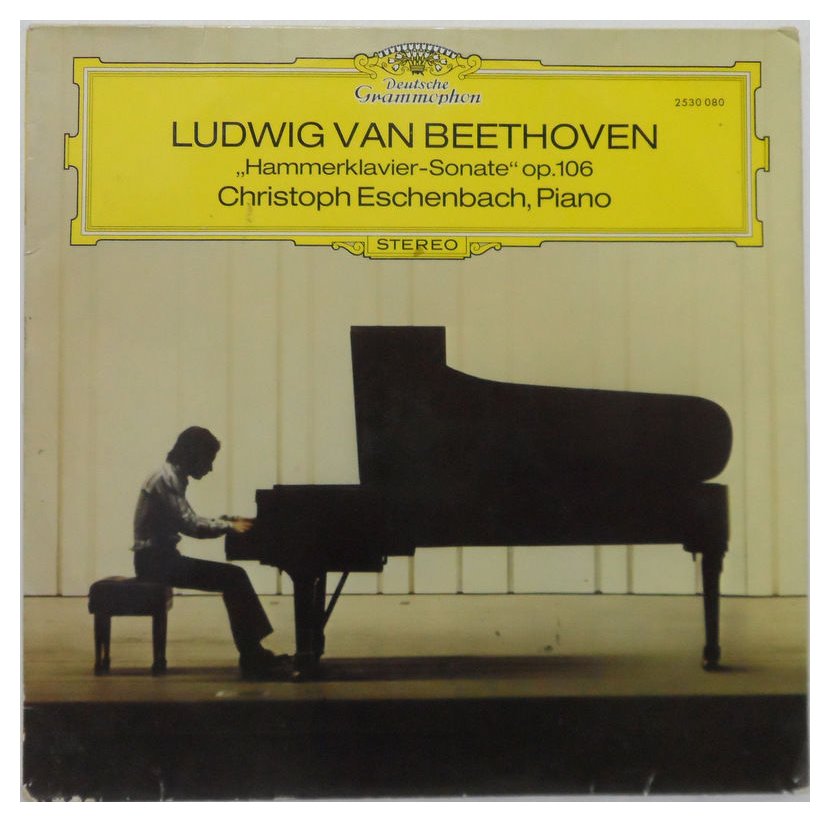

revelatory. In 1964, he made his first recording for Deutsche Grammophon and

signed a contract with the label.

He was soon essaying a wide repertory in concert tours throughout Europe

and America. Notable in his programs were a large number of works from 20th

century composers, such as Béla Bartók, Henze, Rihm, Reimann, Blacher, and

Ruzicka. His performances of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert were considered

revelatory. In 1964, he made his first recording for Deutsche Grammophon and

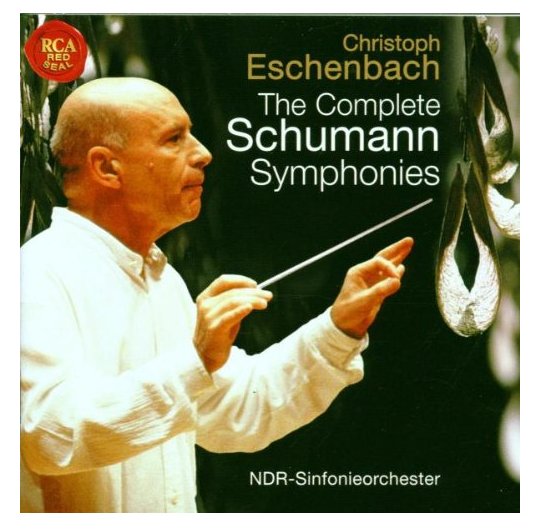

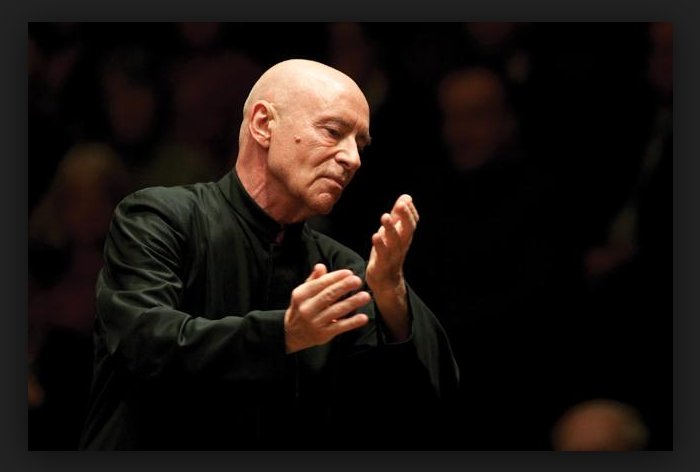

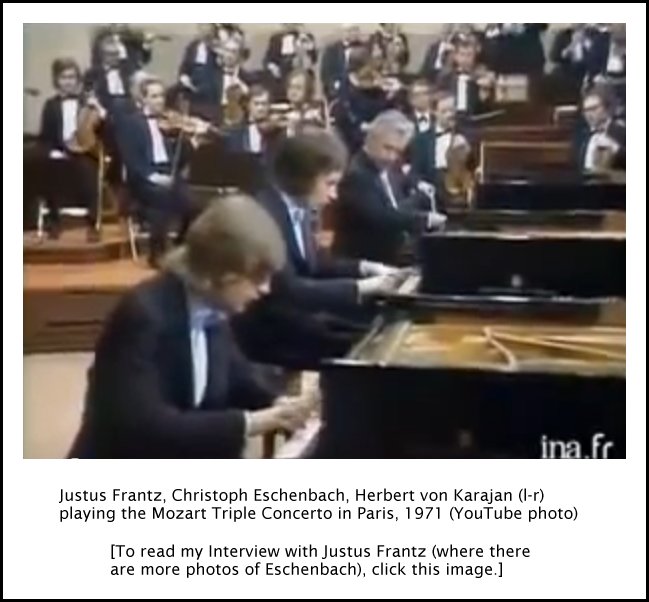

signed a contract with the label.Herbert von Karajan was his mentor for nearly twenty-five years. Eschenbach made his conducting debut in 1972 with a performance of Bruckner's Symphony No. 3, soon followed by Verdi's La Traviata at Darmstadt in 1978. In 1979 he was named general music director of the Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic. In 1981, he became principal guest conductor of the Tonhalle Orchestra Zürich, and from 1982 to 1986 held the posts of Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Orchestra. In 1988 Eschenbach began his association as Music Director of the Houston Symphony Orchestra, where he remained until 1999. Although the Orchestra was already established as one of America's finer major symphonies, Eschenbach improved its musical quality, heightened its national and international reputation, and broadened its repertory. He also formed the Houston Symphony Chamber Players from its ranks. The Houston Symphony Orchestra toured Japan and Europe under his tenure as well made several recordings with Koch International Classics, Virgin, RCA Red Seal, Telarc, and Carlton labels. These included standard fare including all of the major Mozart wind concertos with the orchestra's own soloists. They also recorded Kurt Weill's The Rise and Fall of the City Mahagonny suite, Tobias Picker's Les Encantadoras, and the violin concertos of John Adams and Philip Glass. Eschenbach's era was marked by a strong relationship with the musicians, who admired him on and off the stage. In honor of his many achievements and tenure with the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the City of Houston placed a bronze commemorative star with his name in front of Jones Hall, the performance home of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. Eschenbach now holds the title of Conductor Laureate of the Houston Symphony Orchestra. Other posts have included Chief Conductor of the NDR Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg from 1998 to 2004; Music Director of the Ravinia Festival, summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from 1994 to 2003; and Artistic Director of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival from 1999 to 2002; and Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris from 2000-2010. Christoph Eschenbach was named the 7th Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, effective as of 2003. Some considered this a controversial appointment because, at the time of the announcement, Eschenbach had not conducted the orchestra in over 4 years and there was a perceived lack of personal chemistry between him and the musicians prior to the appointment. Partway into his tenure, his initial 3-year contract was renewed to 2008. In August 2007, the orchestra announced extended guest-conducting periods for Eschenbach with the ensemble in the 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 seasons, after the scheduled conclusion of his tenure as Music Director. In the 2008-2009 season, Christoph Eschenbach took the Orchestre de Paris to the Berlin Festival, the BBC Proms, and on a tour of Scandinavia, and he led the Philadelphia Orchestra on a 3-week European tour. Other highlights included return engagements with the Wiener Philharmoniker (both in Vienna and on tour throughout Europe), New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Dresden Staatskapelle, London Philharmonic Orchestra, and Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as well as his concerts with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam. In the 2009-2010 season, Eschenbach returned to the Wiener Philharmoniker at the Mozartwoche in Salzburg, where he played and conducted, and to the Philadelphia Orchestra to lead two programs, one of which included Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in Carnegie Hall - completing his Mahler cycle with the orchestra. Eschenbach also conducted two programs at Royal Festival Hall with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and took the orchestra on a tour of China. He also returned to the Dresden Staatskapelle, conducting its annual nationally televised Advent Concert, subscription concerts in Dresden, and a tour throughout Germany and in Abu Dhabi.

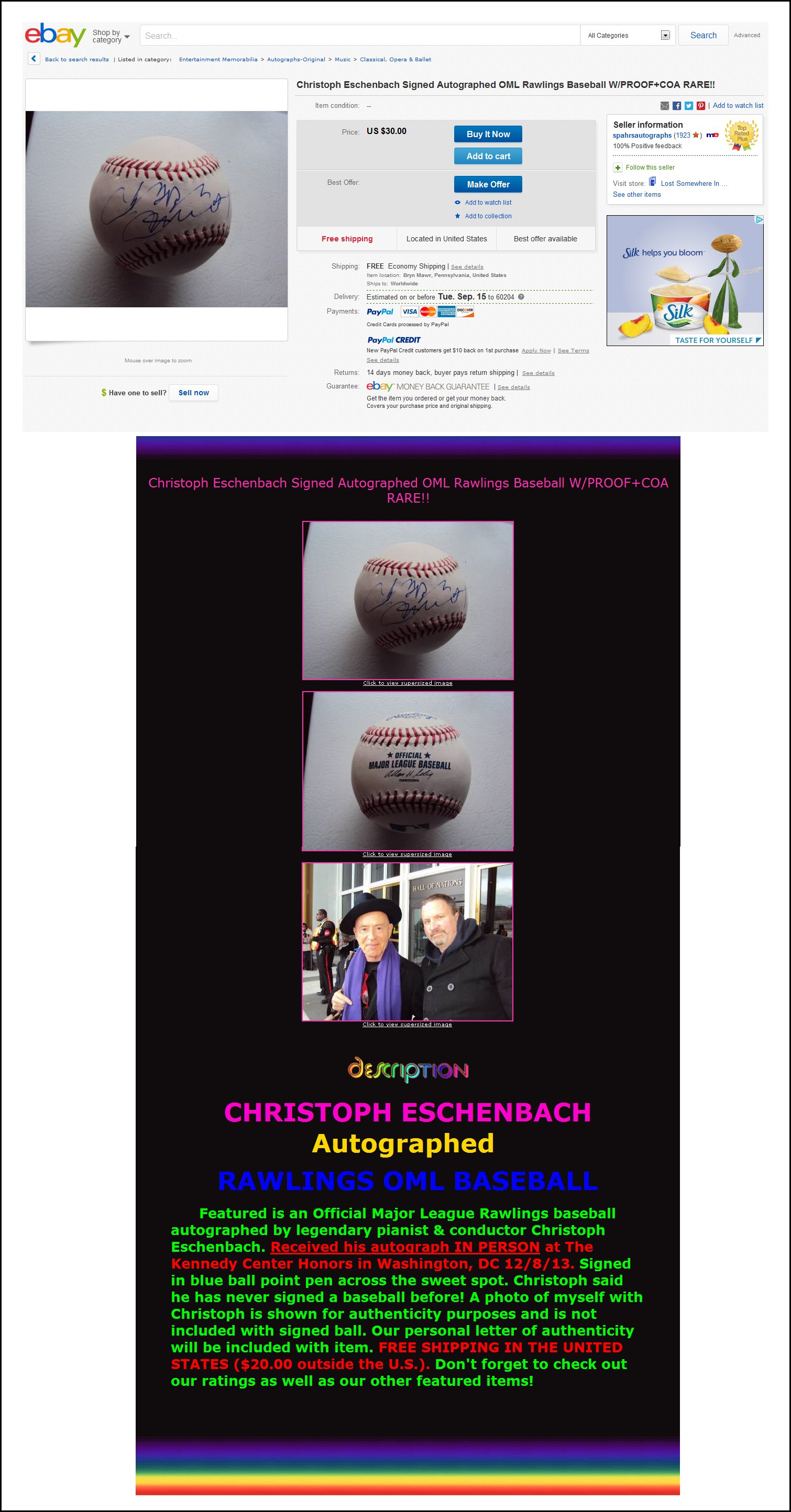

In demand as a distinguished guest conductor with the finest orchestras and opera houses throughout the world, Eschenbach is Music Director of the National Symphony Orchestra, as well as Music Director of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in Washington, D.C. He assumed these posts beginning with the 2010-2011 season. A prolific recording artist over five decades, Eschenbach has an impressive discography (over 80 recordings) as both a conductor and a pianist on a number of prominent labels. His recordings include works ranging from J.S. Bach to music of our time, and reflect his commitment to not just canonical works but the music of the late-20th and early-21st century as well, a number of which have received prestigious honors including BBC Magazine’s “Disc of the Month,” Gramophone’s “Editor’s Choice,” and the German Record Critics’ Award, among others. His recent Ondine recording of the music of Kaija Saariaho with the Orchestre de Paris and soprano Karita Mattila won the 2009 MIDEM Classical Award in Contemporary Music. Eschenbach has also appeared in several television documentaries, and has made many concert broadcasts for different European, Japanese and USA networks. Eschenbach is credited with helping and supporting talented young musicians in their career development, including soprano Renée Fleming, pianists Tzimon Barto and Lang Lang, cellist Claudio Bohórquez, and soprano Marisol Montalvo. He was made a Chevalier (knight) of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, presented by French Culture Minister Renaud Donnedieu de Vabres in June 2006; in October 2002, he was present with the Legion d'honneur by French President Jacques Chirac; and in August 2002, the Officer's Cross with Star and Ribbon of the Verdienstorden der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (German Order of Merit), and the Commander's Cross of the German Order of Merit in 1993 for outstanding achievements as pianist and conductor. He also received the Leonard Bernstein Award from the Pacific Music Festival, where he was co-artistic director from 1992 to 1998, along with Michael Tilson Thomas. -- Names which are links refer

to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

BD: With something new that you find tonight, will

you then incorporate that into all your further performances, or will it be

just something for the moment?

BD: With something new that you find tonight, will

you then incorporate that into all your further performances, or will it be

just something for the moment? BD: What about new works? What do you

look for in a new work, to decide if you will try it out on the public?

BD: What about new works? What do you

look for in a new work, to decide if you will try it out on the public?

BD: For some reason we have avoided the name Mozart

in this conversation so far. Tell me the secret of performing Mozart.

BD: For some reason we have avoided the name Mozart

in this conversation so far. Tell me the secret of performing Mozart. CE: No.

CE: No. BD: So it’s an instinctive and a dramatic thing,

rather than a purely word-oriented thing?

BD: So it’s an instinctive and a dramatic thing,

rather than a purely word-oriented thing?

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the Ravinia Festival on August 10,

1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in

1995 and 2000; and on WNUR in 2004 and 2009. This transcription

was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.