A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

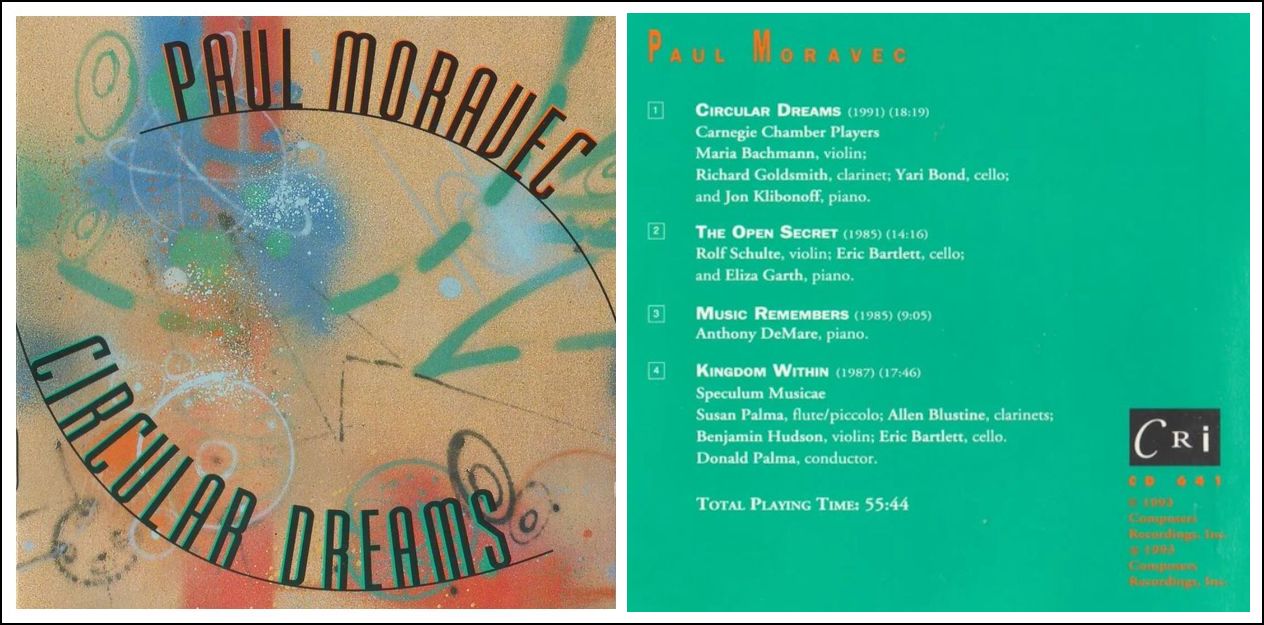

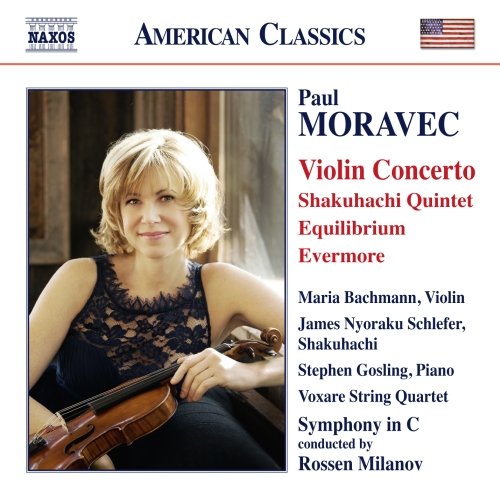

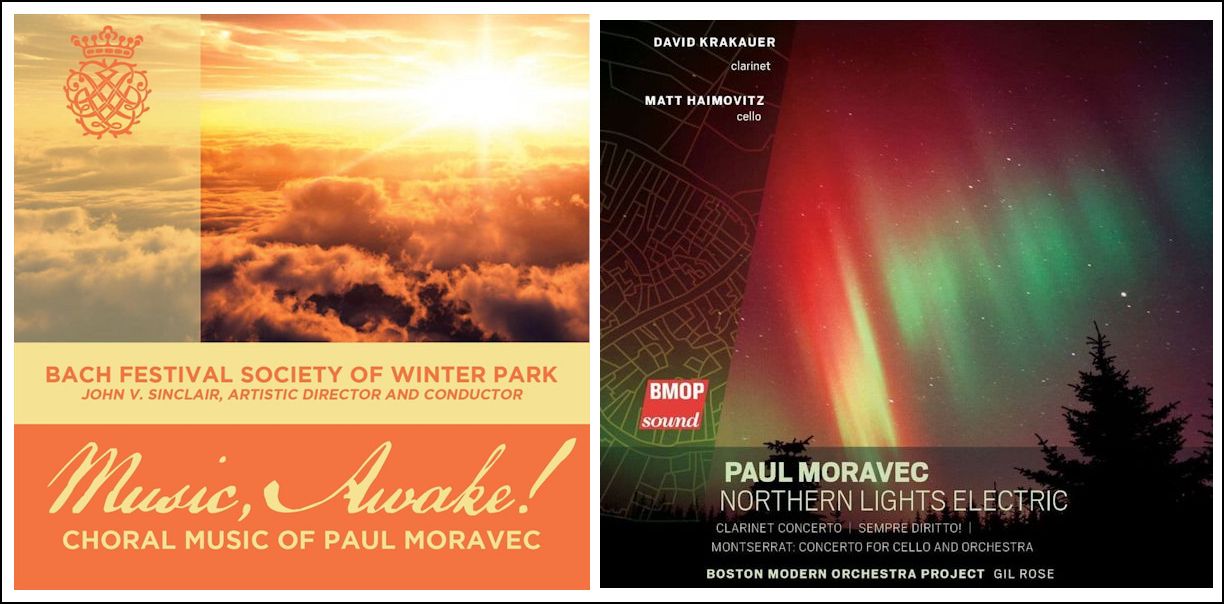

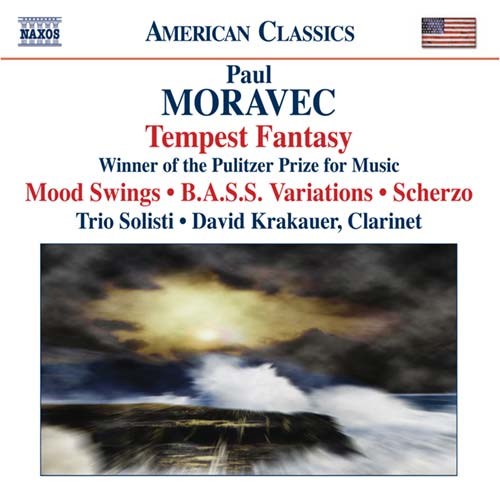

| Paul Moravec (born

November 2, 1957), recipient of the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in Music, is

the composer of numerous orchestral, chamber, choral, operatic, and lyric

pieces. His music has earned many distinctions, including the Rome Prize

Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, three awards from the American Academy

of Arts and Letters, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the

Arts and the Rockefeller Foundation. A graduate of Harvard College and

Columbia University, he has taught at Columbia, Dartmouth, and Hunter College

and currently holds the special position of University Professor

at Adelphi University. He was the 2013 Paul Fromm Composer-in-Residence

at the American Academy in Rome, served as Artist-in-Residence at the

Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ, and was also elected to

membership in the American Philosophical Society. |

Bruce Duffie: Does a sense of humor help in

the composition of music by showing up in the tones that you put down

on the page?

Bruce Duffie: Does a sense of humor help in

the composition of music by showing up in the tones that you put down

on the page? Moravec: Yes... a special deal.

[Laughs]

Moravec: Yes... a special deal.

[Laughs]| Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (born

29 September 1934) is a Hungarian-American psychologist. He recognised

and named the psychological concept of flow, a highly focused mental

state conducive to productivity. He is the Distinguished Professor of

Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. He is the

former head of the department of psychology at the University of Chicago

and of the department of sociology and anthropology at Lake Forest College. His family name derives from the village of Csíkszentmihály in Transylvania. He was the third son of a career diplomat at the Hungarian Consulate in Fiume. His two older half-brothers died when Csikszentmihalyi was still young; one was an engineering student who was killed in the Siege of Budapest, and the other was sent to labor camps in Siberia by the Soviets.

He is noted for his work in the study of happiness and creativity, but is best known as the architect of the notion of flow and for his years of research and writing on the topic. He is the author of many books and over 290 articles or book chapters. Martin Seligman, former president of the American Psychological Association, described Csikszentmihalyi as the world's leading researcher on positive psychology. In his seminal work, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Csíkszentmihályi outlines his theory that people are happiest when they are in a state of flow—a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation. It is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter. The idea of flow is identical to the feeling of being in the zone or in the groove. The flow state is an optimal state of intrinsic motivation, where the person is fully immersed in what they are doing. This is a feeling everyone has at times, characterized by a feeling of great absorption, engagement, fulfillment, and skill—and during which temporal concerns (time, food, ego-self, etc.) are typically ignored. In an interview with Wired magazine, Csíkszentmihályi described flow as "being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you're using your skills to the utmost." |

Moravec: Oh yes, and that can

go on for weeks. I try not to do anything twice. I’ve written

about ninety pieces, and I wonder, “What I haven’t

I done before?” It’s a test. Let

me see what I can do that I haven’t already done. Of course, I

have a certain signature that will come back

— certain chord progressions, or whatever

— but I’m always looking to just do something

I haven’t done before. Sometimes that can make me try to be too

clever, and when you’re trying to be too clever, sometimes the piece will

just snap back at you and say, “No, just relax.”

Moravec: Oh yes, and that can

go on for weeks. I try not to do anything twice. I’ve written

about ninety pieces, and I wonder, “What I haven’t

I done before?” It’s a test. Let

me see what I can do that I haven’t already done. Of course, I

have a certain signature that will come back

— certain chord progressions, or whatever

— but I’m always looking to just do something

I haven’t done before. Sometimes that can make me try to be too

clever, and when you’re trying to be too clever, sometimes the piece will

just snap back at you and say, “No, just relax.” BD: Have you ever really achieved

an ideal, or is this just the next step in terms of ‘good’

and ‘better’ of what you’re

doing?

BD: Have you ever really achieved

an ideal, or is this just the next step in terms of ‘good’

and ‘better’ of what you’re

doing?

BD: Are you part of the solution, or is this off

someplace else and you can’t do anything about it?

BD: Are you part of the solution, or is this off

someplace else and you can’t do anything about it?

BD: [Remembering the film] It’s

in the little statue!

BD: [Remembering the film] It’s

in the little statue! BD: I wish you lots of continued

success, and hope you continue thinking outside your box, so that your

box gets bigger and bigger and bigger.

BD: I wish you lots of continued

success, and hope you continue thinking outside your box, so that your

box gets bigger and bigger and bigger.© 2006 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 28, 2006. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following year, and again in 2018; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2007, and 2014. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.