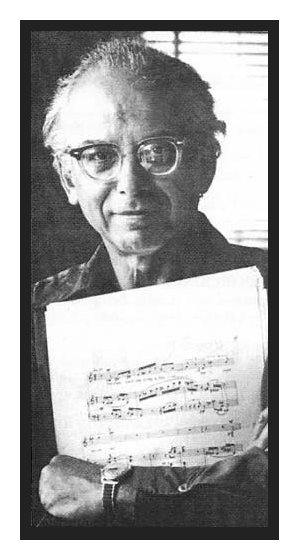

The recipient of a Pulitzer Prize,

a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, and an array of other major awards and

honors, George Perle occupies a commanding position among American composers

of our time. Born in Bayonne, NJ, May 6, 1915, he received his early musical

education in Chicago. After graduation from DePaul University, where he studied

composition with Wesley LaViolette, and subsequent private studies with Ernst Krenek, Perle served

in the US Army during World War II. After the War, he took post-graduate

work in musicology at New York University. His PhD thesis became his first

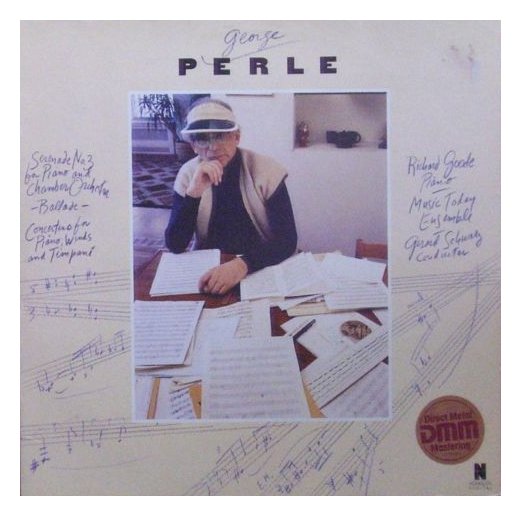

book, Serial Composition and Atonality, now in its sixth edition. Perle’s music has been widely performed in this country and abroad. Major

commissions have resulted in significant works, among them Serenade III (1983) for solo piano and

chamber orchestra, choreographed by American Ballet Theater and nominated

in a Nonesuch recording, for a Grammy Award (1986); Woodwind Quintet No.4 (Pulitzer Prize,

1986); Piano Concerto No.1 (1990),

commissioned for Richard

Goode during Perle’s residency with the San Francisco Symphony; Piano Concerto No.2 (1992), commissioned

by Michael Boriskin; Transcendental Modulations

for Orchestra, commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for its 150th

anniversary; and Thirteen Dickinson Songs

(1978) commissioned by Bethany Beardslee.

Recent works include Brief Encounters

(fourteen movements for string quartet), Nine Bagatelles for piano, Critical Moments and Critical Moments 2 for six players, and

Triptych for solo violin and

piano. A particularly notable portion of Perle’s catalog consists of pieces

for solo piano, many of which have been recorded by Michael Boriskin on New

World Records.

Perle’s music has been widely performed in this country and abroad. Major

commissions have resulted in significant works, among them Serenade III (1983) for solo piano and

chamber orchestra, choreographed by American Ballet Theater and nominated

in a Nonesuch recording, for a Grammy Award (1986); Woodwind Quintet No.4 (Pulitzer Prize,

1986); Piano Concerto No.1 (1990),

commissioned for Richard

Goode during Perle’s residency with the San Francisco Symphony; Piano Concerto No.2 (1992), commissioned

by Michael Boriskin; Transcendental Modulations

for Orchestra, commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for its 150th

anniversary; and Thirteen Dickinson Songs

(1978) commissioned by Bethany Beardslee.

Recent works include Brief Encounters

(fourteen movements for string quartet), Nine Bagatelles for piano, Critical Moments and Critical Moments 2 for six players, and

Triptych for solo violin and

piano. A particularly notable portion of Perle’s catalog consists of pieces

for solo piano, many of which have been recorded by Michael Boriskin on New

World Records.Perle's compositions have figured on the programs of Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, New York Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic, BBC, and other major orchestras in this country and abroad. Perle's works are recorded on Nonesuch, Harmonia Mundi, New World, Albany, CRI and other labels. He has been a frequent Visiting Composer at the Tanglewood Music Festival and Composer-in-Residence with the San Francisco Symphony. Though Perle is above all a composer, the breadth of his musical interests has led to significant contributions in theory and musicology as well. He has published numerous articles in scholarly journals and seven books, including the award-winning Operas of Alban Berg. He has been a guest professor at major universities and a much sought after lecturer and commentator on TV, here and abroad. He is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York. As music critic Andrew Porter has written, “Perle’s renown as an analyst and scholar may have diverted some of the attention that should be given to his merits as a composer…What matters to listeners is his achievement: the vividness of his melodic gestures, the lively rhythmic sense, the clarity and shapeliness of his discourse and, quite simply, the charm and grace of his utterance.” © 2007 George Perle. All rights reserved. -- This biography was taken from

the official George Perle website

-- Names which are links (both here and in the interview below) refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

BD: Do you find that performers or conductors discover

things in your music that even you did not know were there?

BD: Do you find that performers or conductors discover

things in your music that even you did not know were there? GP: There isn’t any conflict between the two things.

For example, the Serenade No. 3 for Piano

and Chamber Orchestra was commissioned. Here is how my conversation

with Frank Taplin, who commissioned the piece, worked. Taplin is a

pianist himself, but he’s also a very well-known and established businessman,

patron of the arts, and former president of the Metropolitan Opera Company.

He wasn’t commissioning these pieces for his own playing, it was just that

the piano is an instrument that he’s interested in. He likes to play

chamber music with the piano, so he was commissioning a number of American

composers to write chamber music for the piano. I had written my first

serenade in 1961, which was for solo viola plus ten-piece orchestra, and

then I’d written my Serenade No.2,

which Koussevitzky commissioned in 1968, which was no solo instrument, but

eleven instruments. So I had these two pieces, each of them with eleven

different instruments. There’s a saxophone included among the woodwinds

in each one of them, which is sort of unusual. Both of these pieces

have five movements, so they sort of participate in a certain musical concept,

really a kind of eighteenth century notion of something which is between

a suite and a symphony, like a divertimento, and I had been thinking ever

since the second one that I would like to write one with a piano solo.

It would also have five movements and be the same kind of scheme as the others.

There was something about the format that I found attractive. The instrumentation

is not exactly the same; it’s a little special in each one. This was

in my mind, that I’d like to write this, so what do you do? Well, you

wait until you have time to write it. You don’t necessarily wait for

a commission, because, I’ll tell you the truth, it’s only in recent years

I’ve been getting enough commissions to be kept busy. If I had depended

on commissions up until eight or ten years ago, I wouldn’t have written much

music.

GP: There isn’t any conflict between the two things.

For example, the Serenade No. 3 for Piano

and Chamber Orchestra was commissioned. Here is how my conversation

with Frank Taplin, who commissioned the piece, worked. Taplin is a

pianist himself, but he’s also a very well-known and established businessman,

patron of the arts, and former president of the Metropolitan Opera Company.

He wasn’t commissioning these pieces for his own playing, it was just that

the piano is an instrument that he’s interested in. He likes to play

chamber music with the piano, so he was commissioning a number of American

composers to write chamber music for the piano. I had written my first

serenade in 1961, which was for solo viola plus ten-piece orchestra, and

then I’d written my Serenade No.2,

which Koussevitzky commissioned in 1968, which was no solo instrument, but

eleven instruments. So I had these two pieces, each of them with eleven

different instruments. There’s a saxophone included among the woodwinds

in each one of them, which is sort of unusual. Both of these pieces

have five movements, so they sort of participate in a certain musical concept,

really a kind of eighteenth century notion of something which is between

a suite and a symphony, like a divertimento, and I had been thinking ever

since the second one that I would like to write one with a piano solo.

It would also have five movements and be the same kind of scheme as the others.

There was something about the format that I found attractive. The instrumentation

is not exactly the same; it’s a little special in each one. This was

in my mind, that I’d like to write this, so what do you do? Well, you

wait until you have time to write it. You don’t necessarily wait for

a commission, because, I’ll tell you the truth, it’s only in recent years

I’ve been getting enough commissions to be kept busy. If I had depended

on commissions up until eight or ten years ago, I wouldn’t have written much

music. BD: So you would dump the writing and keep the composing,

if you had the choice, if it was of necessity?

BD: So you would dump the writing and keep the composing,

if you had the choice, if it was of necessity? BD: This is not necessarily a good thing, then?

BD: This is not necessarily a good thing, then? GP: [Sighs] People have asked me that because

I’ve been so involved with opera, and because I read all the time and I’m

interested in literature. It’s my one great love next to music.

The reason is because an opera is not something I would write on my own.

[Laughs] In the days when I didn’t get commissions, I would write a

string quartet on my own. Now, if I get a commission I can twist it

around, turn it around into something I want to write, or I may get interested

in what’s proposed. That’s what it is with the bass trombone piece,

which I mentioned. I got interested in the combination. I hadn’t

thought of it. Then I converted it into the concept that I was interested

in, and when the bass trombonist said, “What about that piece I suggested

with the text and the baritone?” I said, “Well that’s not...” There

was a long silence, and then he said, “I know why. It’s because you

heard it that way,” which is what you said. I was very pleased that

the performer who was commissioning the piece should have responded in this

way. That piece is just about finished now. I also have a commission

from the Houston Symphony for a ten-minute first-piece-on-a-program.

I’m told that there’s hardly any music by American composers that is good

for opening a program. I hadn’t thought about that, but I always love

to write for orchestra. As a matter of fact, my Short Symphony has been used for that

kind of an opener. It’s had about a half a dozen performances, and

I think on almost every one of the performances, the conductor decided to

play it first.

GP: [Sighs] People have asked me that because

I’ve been so involved with opera, and because I read all the time and I’m

interested in literature. It’s my one great love next to music.

The reason is because an opera is not something I would write on my own.

[Laughs] In the days when I didn’t get commissions, I would write a

string quartet on my own. Now, if I get a commission I can twist it

around, turn it around into something I want to write, or I may get interested

in what’s proposed. That’s what it is with the bass trombone piece,

which I mentioned. I got interested in the combination. I hadn’t

thought of it. Then I converted it into the concept that I was interested

in, and when the bass trombonist said, “What about that piece I suggested

with the text and the baritone?” I said, “Well that’s not...” There

was a long silence, and then he said, “I know why. It’s because you

heard it that way,” which is what you said. I was very pleased that

the performer who was commissioning the piece should have responded in this

way. That piece is just about finished now. I also have a commission

from the Houston Symphony for a ten-minute first-piece-on-a-program.

I’m told that there’s hardly any music by American composers that is good

for opening a program. I hadn’t thought about that, but I always love

to write for orchestra. As a matter of fact, my Short Symphony has been used for that

kind of an opener. It’s had about a half a dozen performances, and

I think on almost every one of the performances, the conductor decided to

play it first.  GP: It is a pleasure.

GP: It is a pleasure.© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 20, 1986.

Portions (along with recordings) were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again

in 1995 and 2000. It was also used in programs on WNUR in 2007 and

2012, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2012. A copy

of the unedited audio was given to the Oral

History of American Music archive at Yale Univeristy. This transcription

was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.