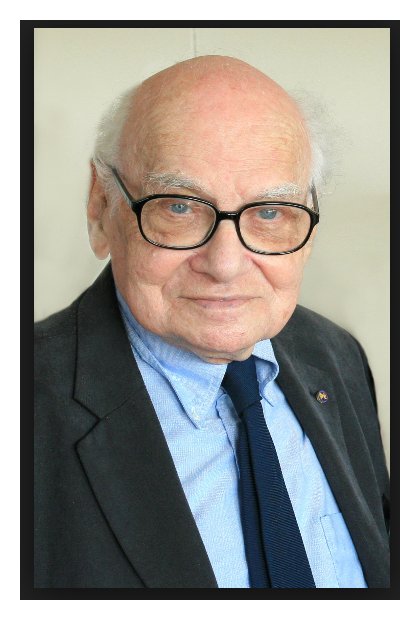

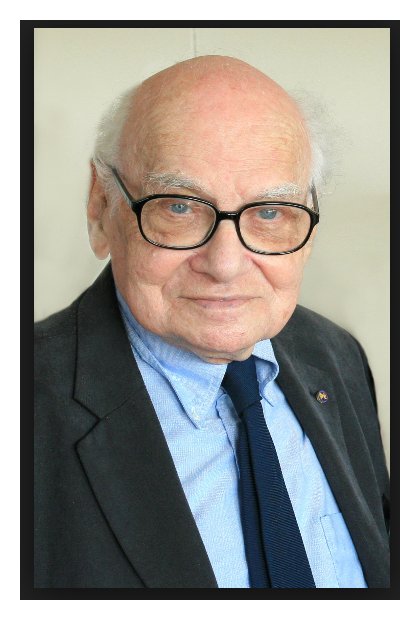

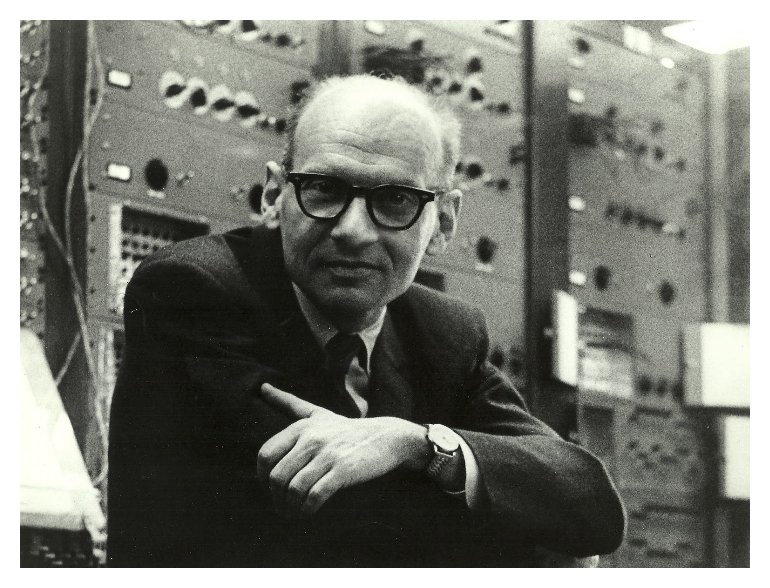

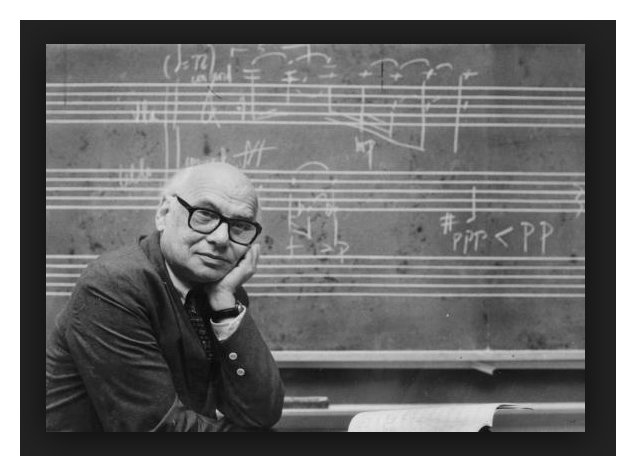

| The compositional and intellectual

wisdom of Milton Babbitt has influenced a wide range of contemporary musicians.

A broad array of distinguished musical achievements in the dodecaphonic system

and important writings on the subject have generated increased understanding

and integration of serialist language into the eclectic musical styles of

the late 20th century. Babbitt is also renowned for his great talent and

instinct for jazz and his astonishing command of American popular music.

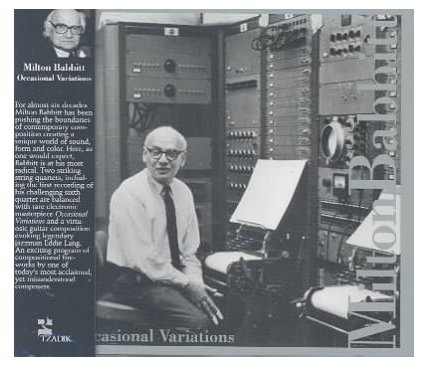

Babbitt was born on 10 May 1916 in Philadelphia and studied composition privately with Roger Sessions. He earned degrees from New York and Princeton Universities and has been awarded honorary degrees from Middlebury College, Swarthmore College, New York University, the New England Conservatory, University of Glasgow, and Northwestern University. He taught at Princeton and The Juilliard School. He died in Princeton, NJ, on 29 January 2011. An extensive catalogue of works for multiple combinations of instruments and voice along with his pioneering achievements in synthesized sound have made Babbitt one of the most celebrated of 20th-century composers. He is a founder and member of the Committee of Direction for the Electronic Music Center of Columbia-Princeton Universities and a member of the Editorial Board of Perspectives of New Music. The recipient of numerous honors, commissions, and awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship and a Pulitzer Prize Citation for his "life's work as a distinguished and seminal American composer." Babbitt is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. |

BD: [Genuinely surprised] Really???

Someone who’s been involved in electronic music for so long???

BD: [Genuinely surprised] Really???

Someone who’s been involved in electronic music for so long??? BD: What advice do you have, then, for the young

composers coming along?

BD: What advice do you have, then, for the young

composers coming along? MB: I would say both. It would be very hard

to discriminate because people who are really going to get deeply involved

in your piece want to see it, and they want to see whether that recording

really represents the piece, and how much is not on that recording.

I have to tell you something else that I hope won’t disappoint you.

For all electronic composer that I have been, and perhaps may be again

— though that’s a purely practical matter — for all of my involvement

allegedly in technology and, God be with us, mathematics, which of course

is totally, totally misunderstood, I don’t like recordings that much!

There’s no substitute for a really good live performance. Just the

dimensionality of it; just the separation; just the possibility of being

able to differentiate and hear things that simply cannot be conveyed by even

the best recording. Nevertheless, that’s not the important issue.

Of course one wants recordings, but one has to have the publication.

How can one sit down and look at a piece, think about a piece, talk about

a piece with a student, if you don’t have publication? But publication

has become almost an impracticality. It’s just about disappeared.

People say, “What about computers for the printing of music?” First

of all, it’s not a matter of just the printing of music. If you sell

one copy, everybody Xeroxes every other copy. You still have to punch

the stuff in for a computer, and that’s expensive. From the standpoint

of printing parts, computers are still not acceptable to many performers.

You can criticize them about that, but the fact remains that there’s a reaction

to it, and it’s going to have an effect on the piece. So we have the

problem of just communicating with our colleagues. People say to me,

“Why don’t you reach out to the masses with your music?” Beyond the

fact that I question the morality that it’s a greater virtue to stoop to

attempt to conquer the masses rather than set a standard to which they might

aspire, I tell them I can’t reach out to my colleagues. I can’t send

them my music and they can’t send me theirs. I don’t know what they’re

doing. I don’t know what a friend of mine at Berkeley is writing these

days. I don’t dare ask him for a score! If he sends me a copy

of his manuscript, it’ll still cost him a hundred and fifty dollars to reproduce

it, and if I get it, I probably will find it very hard to read because it’s

in his handwriting. The poet, after all, can sit with his word processor

— or if he still uses a typewriter or even long hand

— and communicate with his fellows. And there are still

publishers who will publish poetry as a matter of principal. Not that

there aren’t music publishers who wouldn’t publish it as a matter of principal,

but principal is not enough. They don’t have any money. They

can’t sell the music of the past anymore. They can’t sell the music

of the past, which used to make the money for them. Then obviously,

they have no money to spend on the music of the present.

MB: I would say both. It would be very hard

to discriminate because people who are really going to get deeply involved

in your piece want to see it, and they want to see whether that recording

really represents the piece, and how much is not on that recording.

I have to tell you something else that I hope won’t disappoint you.

For all electronic composer that I have been, and perhaps may be again

— though that’s a purely practical matter — for all of my involvement

allegedly in technology and, God be with us, mathematics, which of course

is totally, totally misunderstood, I don’t like recordings that much!

There’s no substitute for a really good live performance. Just the

dimensionality of it; just the separation; just the possibility of being

able to differentiate and hear things that simply cannot be conveyed by even

the best recording. Nevertheless, that’s not the important issue.

Of course one wants recordings, but one has to have the publication.

How can one sit down and look at a piece, think about a piece, talk about

a piece with a student, if you don’t have publication? But publication

has become almost an impracticality. It’s just about disappeared.

People say, “What about computers for the printing of music?” First

of all, it’s not a matter of just the printing of music. If you sell

one copy, everybody Xeroxes every other copy. You still have to punch

the stuff in for a computer, and that’s expensive. From the standpoint

of printing parts, computers are still not acceptable to many performers.

You can criticize them about that, but the fact remains that there’s a reaction

to it, and it’s going to have an effect on the piece. So we have the

problem of just communicating with our colleagues. People say to me,

“Why don’t you reach out to the masses with your music?” Beyond the

fact that I question the morality that it’s a greater virtue to stoop to

attempt to conquer the masses rather than set a standard to which they might

aspire, I tell them I can’t reach out to my colleagues. I can’t send

them my music and they can’t send me theirs. I don’t know what they’re

doing. I don’t know what a friend of mine at Berkeley is writing these

days. I don’t dare ask him for a score! If he sends me a copy

of his manuscript, it’ll still cost him a hundred and fifty dollars to reproduce

it, and if I get it, I probably will find it very hard to read because it’s

in his handwriting. The poet, after all, can sit with his word processor

— or if he still uses a typewriter or even long hand

— and communicate with his fellows. And there are still

publishers who will publish poetry as a matter of principal. Not that

there aren’t music publishers who wouldn’t publish it as a matter of principal,

but principal is not enough. They don’t have any money. They

can’t sell the music of the past anymore. They can’t sell the music

of the past, which used to make the money for them. Then obviously,

they have no money to spend on the music of the present. MB: I know. See that’s what concerns them!

What concerns us is let ‘em copy! I think that more and more students

are going to have to turn to them. Somebody says, “Why do you have

to turn these people into technicians?” Well, why did you have to turn

them into pianists at one time? Why did you have to turn them into instrumentalists?

We all grew up as instrumentalists. This is their instrument, and I

think most of them are going to feel that way. Those who want to play

the piano and those who want to play the violin will continue to do so.

We’re not interested in supplanting any performers. We’re interested

in supplementing the resources of music.

MB: I know. See that’s what concerns them!

What concerns us is let ‘em copy! I think that more and more students

are going to have to turn to them. Somebody says, “Why do you have

to turn these people into technicians?” Well, why did you have to turn

them into pianists at one time? Why did you have to turn them into instrumentalists?

We all grew up as instrumentalists. This is their instrument, and I

think most of them are going to feel that way. Those who want to play

the piano and those who want to play the violin will continue to do so.

We’re not interested in supplanting any performers. We’re interested

in supplementing the resources of music. MB: One of the things that’s concerned me the most

is our position in the university community and therefore our position in

the community at large is why music, virtually alone, has been subjected

to such arrogant, cavalier presumption on the part of people in other fields?

I have a quotation here. I don’t usually quote people positively;

I usually quote them negatively. I’ve collected these over

the years, but for a positive one, here’s this by Nelson Goodman apropos

of the question of music as amusement. He says, “My argument, that

the arts must be taken not less seriously and no less seriously than the

sciences, is not that the arts enrich us or contribute something warmer or

more human, but that the sciences, as distinguished from technology, and

the arts, as distinguished from fun, have as their common function the advancement

of understanding.” That’s how we mean understanding. Understanding

of what? Certainly not some understanding about some banal mundanities

or understanding of some human emotions, no. What I think he means about

understanding music is what music can be, what musical relationships can

do, and that, certainly, is a form of amusement. It is! I think

one could also say they’re categories. Let’s not confuse categories.

To confuse categories is immediately to inhibit serious discussion, to vitiate

any kind of real understanding of the problems of the states of our art at

this time. I would hope that people would be seriously amused, seriously

entertained by the wonderful stuff that music can be, by the rich ramifications

of musical relationships. It’s hard to describe, because after all,

what is one hearing in the Brahms Third

Symphony? For some of us, one is hearing the most extraordinary

use of musical materials that one can possibly imagine. I sing a lot

about the Brahms Third only because

it might seem to many people by now a war horse, and to some of us will never

be a war horse because that horse keeps running and running and running.

But it’s certainly a problem. What you’re really asking is even a more

difficult problem to answer, and that is where does my music and the music

of some of my colleagues fit into all of this? Obviously there is a

music which is an entertainment, a music which is in the elevators.

I’m not belittling any of this. It doesn’t interest me to say this

is trivial pop music. There is sort of simplistic, so-called serious

music, which derives from pop. They’re all music, and what happens

to interest me is not the only music that I would suggest should be interesting

because lots of music interests me. However, it’s ridiculous for us

to be unrealistic about this, and not recognize the fact that for most people,

our music doesn’t mean a thing! They don’t buy the records. They

don’t go to hear it. We have these small audiences that are interested

in our music. They’re mainly fellow professionals. That doesn’t

concern me that they’re fellow professionals, but it’s ridiculous not to

face the fact that music has changed, and changed in fundamental ways that

should not be minimized by those who would invoke their superior historical

conception, their historical sense of what has happened to music. I’ll

invoke my age at this point. I’m going to be realistic about this.

About fifty years ago or maybe even a little more, we were constantly being

told by our elders and sometimes not even by our elders, “You’re dramatizing

yourself.” Music hasn’t really changed this much. We were told

about the Schoenberg Orchestral Variations,

which at that time was perhaps just a decade old, to just wait and see.

It will either become standard repertory and be part of every orchestra’s

repertory, or it will just disappear. Neither has happened. It

is not standard repertory. The Chicago Symphony once played it under

Martinon, and I have not heard it in New York more than once or twice in

the past fifteen years. However, here is a work which every young composer

would take for granted belongs to the tradition of music. It might

even belong to the past for him. It’s one of those classics that you

turn to, that you study in school as certainly as you study the Eroica Symphony. That is the beginning

of what was once a dichotomy and now a multi-chotomy. We have to face

the fact that music has changed in fundamental ways that we cannot minimize!

Ralph Shapey has just called the orchestra a musical museum. Okay.

That’s fair. After all, one does not depreciate museums. We go

to museums; we enjoy them; they have a very well defined function, educationally,

societally. Once music leaves the museums, once it leaves these citadels

of show biz, the public salons, and moves to the university it’s for this

reason. There’s no other place it can be accommodated. After

all, Ralph has a performance group here that does contemporary music at the

University of Chicago. In New York, even when the groups are not officially

associated with the university, as the Speculum is with Columbia, we have

others that are. They are basically people who themselves have university

associations, but it’s true that the groups are diminishing in there.

They’re having more and more and more trouble because the support isn’t there.

If one wants to talk about nitty-gritty, the Ford Foundation, which once

subsidized recording and publication is out of the business. The Rockefeller,

which once did that very crucial, but from a publicity

point of view, not very rewarding task of paying for extra rehearsal time

for orchestras, is out of the business. The Martha Baird Rockefeller

Foundation, which once paid for subsidized recordings and also work by music

historians has closed shop.

MB: One of the things that’s concerned me the most

is our position in the university community and therefore our position in

the community at large is why music, virtually alone, has been subjected

to such arrogant, cavalier presumption on the part of people in other fields?

I have a quotation here. I don’t usually quote people positively;

I usually quote them negatively. I’ve collected these over

the years, but for a positive one, here’s this by Nelson Goodman apropos

of the question of music as amusement. He says, “My argument, that

the arts must be taken not less seriously and no less seriously than the

sciences, is not that the arts enrich us or contribute something warmer or

more human, but that the sciences, as distinguished from technology, and

the arts, as distinguished from fun, have as their common function the advancement

of understanding.” That’s how we mean understanding. Understanding

of what? Certainly not some understanding about some banal mundanities

or understanding of some human emotions, no. What I think he means about

understanding music is what music can be, what musical relationships can

do, and that, certainly, is a form of amusement. It is! I think

one could also say they’re categories. Let’s not confuse categories.

To confuse categories is immediately to inhibit serious discussion, to vitiate

any kind of real understanding of the problems of the states of our art at

this time. I would hope that people would be seriously amused, seriously

entertained by the wonderful stuff that music can be, by the rich ramifications

of musical relationships. It’s hard to describe, because after all,

what is one hearing in the Brahms Third

Symphony? For some of us, one is hearing the most extraordinary

use of musical materials that one can possibly imagine. I sing a lot

about the Brahms Third only because

it might seem to many people by now a war horse, and to some of us will never

be a war horse because that horse keeps running and running and running.

But it’s certainly a problem. What you’re really asking is even a more

difficult problem to answer, and that is where does my music and the music

of some of my colleagues fit into all of this? Obviously there is a

music which is an entertainment, a music which is in the elevators.

I’m not belittling any of this. It doesn’t interest me to say this

is trivial pop music. There is sort of simplistic, so-called serious

music, which derives from pop. They’re all music, and what happens

to interest me is not the only music that I would suggest should be interesting

because lots of music interests me. However, it’s ridiculous for us

to be unrealistic about this, and not recognize the fact that for most people,

our music doesn’t mean a thing! They don’t buy the records. They

don’t go to hear it. We have these small audiences that are interested

in our music. They’re mainly fellow professionals. That doesn’t

concern me that they’re fellow professionals, but it’s ridiculous not to

face the fact that music has changed, and changed in fundamental ways that

should not be minimized by those who would invoke their superior historical

conception, their historical sense of what has happened to music. I’ll

invoke my age at this point. I’m going to be realistic about this.

About fifty years ago or maybe even a little more, we were constantly being

told by our elders and sometimes not even by our elders, “You’re dramatizing

yourself.” Music hasn’t really changed this much. We were told

about the Schoenberg Orchestral Variations,

which at that time was perhaps just a decade old, to just wait and see.

It will either become standard repertory and be part of every orchestra’s

repertory, or it will just disappear. Neither has happened. It

is not standard repertory. The Chicago Symphony once played it under

Martinon, and I have not heard it in New York more than once or twice in

the past fifteen years. However, here is a work which every young composer

would take for granted belongs to the tradition of music. It might

even belong to the past for him. It’s one of those classics that you

turn to, that you study in school as certainly as you study the Eroica Symphony. That is the beginning

of what was once a dichotomy and now a multi-chotomy. We have to face

the fact that music has changed in fundamental ways that we cannot minimize!

Ralph Shapey has just called the orchestra a musical museum. Okay.

That’s fair. After all, one does not depreciate museums. We go

to museums; we enjoy them; they have a very well defined function, educationally,

societally. Once music leaves the museums, once it leaves these citadels

of show biz, the public salons, and moves to the university it’s for this

reason. There’s no other place it can be accommodated. After

all, Ralph has a performance group here that does contemporary music at the

University of Chicago. In New York, even when the groups are not officially

associated with the university, as the Speculum is with Columbia, we have

others that are. They are basically people who themselves have university

associations, but it’s true that the groups are diminishing in there.

They’re having more and more and more trouble because the support isn’t there.

If one wants to talk about nitty-gritty, the Ford Foundation, which once

subsidized recording and publication is out of the business. The Rockefeller,

which once did that very crucial, but from a publicity

point of view, not very rewarding task of paying for extra rehearsal time

for orchestras, is out of the business. The Martha Baird Rockefeller

Foundation, which once paid for subsidized recordings and also work by music

historians has closed shop. MB: You know about this very well! He kept

more than an eye on it. You’re absolutely right and the answer is I

don’t know, and I don’t know that anybody else does. I’ve asked that

question as recently as yesterday, and I don’t think the answer is yet clear.

The Fromm Foundation was a remarkable phenomenon.

MB: You know about this very well! He kept

more than an eye on it. You’re absolutely right and the answer is I

don’t know, and I don’t know that anybody else does. I’ve asked that

question as recently as yesterday, and I don’t think the answer is yet clear.

The Fromm Foundation was a remarkable phenomenon.  MB: You’re thinking to the next piece, yes.

It’s not just a matter of moving on, though of course, you’re right.

It’s rather a matter of thinking I have ideas for another piece. I

don’t want to be influenced by my last piece. As I sit there imagining

this music in my mind, I don’t want to think is this okay because it was

once okay? Is this something that worked in my last piece or something

that sounded right? I don’t care what terms you use, is that why I’m

accepting it here? I want to think within this piece. That’s

another reason why I — and I think most of my colleagues

— can only work on only one piece at a time, because that is the

one piece in our mind. We don’t want any other piece to influence it,

even another one of our own pieces. It’s a true fact of contemporary

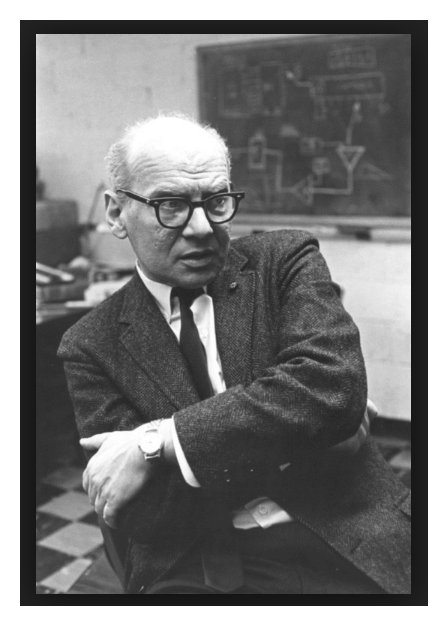

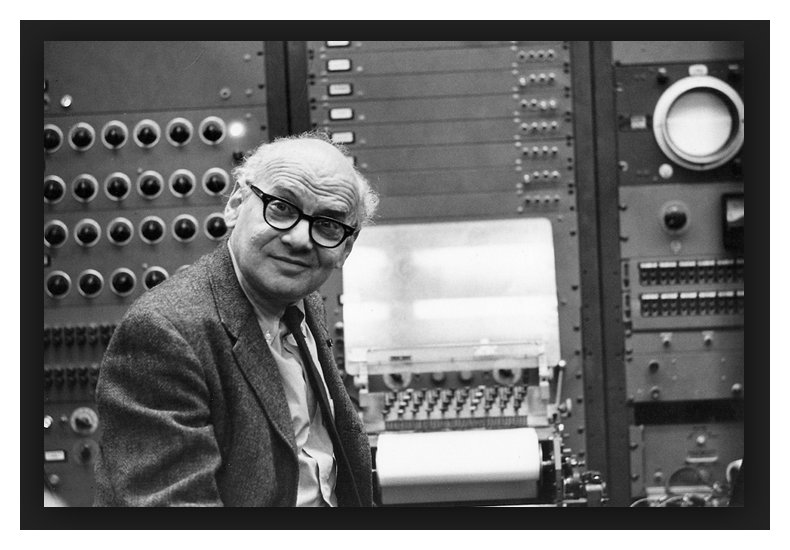

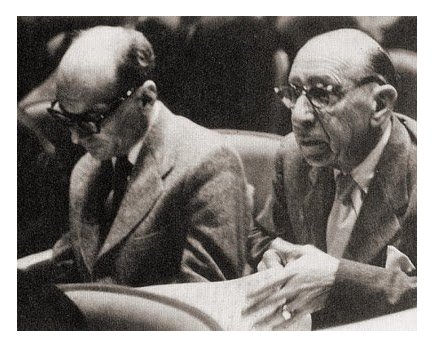

music. It was true of late Stravinsky [with Babbitt in photo at right] as much

as any of our music — and I say this only because one

will regard Stravinsky as being in a far grander tradition — that each of

our works is really singular. I’m not using ‘singular’

in an evaluative, normative sense. I simply mean that each work is

much more self-contained, much more autonomous. I like to use a word

that, unfortunately, sounds too mathematical. We use the word ‘contextual’

to talk about the fact that the music is self-referential. Automorphic

is a word that I love. It has nothing to do with mathematics.

I mean automorphic in the sense of creating its own forms. This is

a relative term. Pieces do not start from nothing, but the lack of

communality that Schoenberg thought he was returning to music with the twelve-tone

idea, has simply not returned to music. So as you come to a piece as

a composer, you’re really thinking much more about this piece than anything

this piece shares with any other piece, be it written by you or by anyone

else. You haven’t internalized such a degree of communality that you

know how the piece is going to go. You’re thinking about it in the

large and in the small at the same time. The local fits into the global.

I know it sounds terribly pretentious, but until you see how the detail is

going to fit into that whole or generate the whole, or how the whole is going

to accommodate that detail, you’re not satisfied to start that piece, to

get it going. At the same time, you don’t want the previous piece to

too strongly suggest, if at all, how you’re going to do it.

MB: You’re thinking to the next piece, yes.

It’s not just a matter of moving on, though of course, you’re right.

It’s rather a matter of thinking I have ideas for another piece. I

don’t want to be influenced by my last piece. As I sit there imagining

this music in my mind, I don’t want to think is this okay because it was

once okay? Is this something that worked in my last piece or something

that sounded right? I don’t care what terms you use, is that why I’m

accepting it here? I want to think within this piece. That’s

another reason why I — and I think most of my colleagues

— can only work on only one piece at a time, because that is the

one piece in our mind. We don’t want any other piece to influence it,

even another one of our own pieces. It’s a true fact of contemporary

music. It was true of late Stravinsky [with Babbitt in photo at right] as much

as any of our music — and I say this only because one

will regard Stravinsky as being in a far grander tradition — that each of

our works is really singular. I’m not using ‘singular’

in an evaluative, normative sense. I simply mean that each work is

much more self-contained, much more autonomous. I like to use a word

that, unfortunately, sounds too mathematical. We use the word ‘contextual’

to talk about the fact that the music is self-referential. Automorphic

is a word that I love. It has nothing to do with mathematics.

I mean automorphic in the sense of creating its own forms. This is

a relative term. Pieces do not start from nothing, but the lack of

communality that Schoenberg thought he was returning to music with the twelve-tone

idea, has simply not returned to music. So as you come to a piece as

a composer, you’re really thinking much more about this piece than anything

this piece shares with any other piece, be it written by you or by anyone

else. You haven’t internalized such a degree of communality that you

know how the piece is going to go. You’re thinking about it in the

large and in the small at the same time. The local fits into the global.

I know it sounds terribly pretentious, but until you see how the detail is

going to fit into that whole or generate the whole, or how the whole is going

to accommodate that detail, you’re not satisfied to start that piece, to

get it going. At the same time, you don’t want the previous piece to

too strongly suggest, if at all, how you’re going to do it. BD: Have you been really pleased with some of the

recent students you’ve had?

BD: Have you been really pleased with some of the

recent students you’ve had?Milton Babbitt

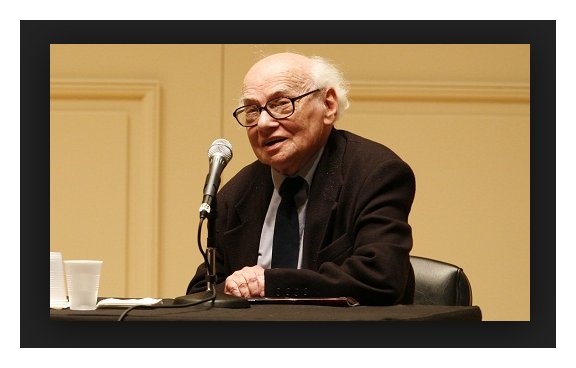

Milton Babbitt, who has died aged 94, was one of the most impenetrable, inaccessible and influential of American composers and theorists; an article he wrote in 1958 headlined "Who cares if you listen" set the tone, reinforcing the view that contemporary music was for an elite cognoscenti. Orchestras rejected his output, critics sneered at its complexity and academics rejected his doctoral thesis. Myths surrounding his wartime background in secret intelligence work did him no favours, with the cultural commentator Alex Ross describing him as an "emblematic Cold War composer" producing music "so Byzantine in construction that one practically needed a security clearance to understand it". Yet Babbitt the serialist composer had his champions, Stephen Sondheim among them, while in the 1960s and 1970s his 12-tone theories, cerebral though they may have been, took root on university campuses, if not in concert halls, across the United States. His supporters, and there were many, argued that his complex music simply required greater involvement and commitment from the listener than had hitherto been the case. In 1951 RCA invited him to be the first composer to work on their Mark II synthesizer at Columbia-Princeton University, exploring new sound worlds in works such as Composition for Synthesizer (1961), Vision and Prayer, for soprano and synthesizer (1961) and Ensembles for Synthesizer (1964). He revelled in distorting musical sounds, seeing how far he could push the boundaries. The resultant tapes would then be used in the concert hall, either alone or with live instrumentalists or singers. Much of his output was for small-scale forces (partly out of necessity, as few orchestras could stomach his works either musically or financially). However, James Levine and the Boston Symphony Orchestra did give the premiere of his Concerto for Orchestra in January 2005. Despite the severity of his music, Babbitt had a mischievous sense of humour, as titles such as Sheer Pluck (1984, for solo guitar) would suggest. While he opened up many fascinating ideas, critics said that Babbitt – who described himself as a maximalist to differentiate from the minimalists – found himself in a musical cul-de-sac. As John Adams wrote: "Atonality, rather than being the promised land, proved to be nothing of the kind. After a heady first planting, the terrain [its] composers discovered was unable to reproduce its initial harvest." Milton Byron Babbitt was born in Philadelphia on May 10 1916, the son of a wealthy actuary who demonstrated to his son the deep pleasure of mathematics. He grew up in Jackson, Mississippi, in the Deep South ("You can't get much deeper, he once noted") where he knew the future author Eudora Welty. At the age of four he was given a violin but, wanting a better social life, turned to clarinet and, later, saxophone as well as writing his own pop songs. He recalled being shown Schönberg's Three Piano Pieces (Op 11) at the age of ten and being fascinated with this "absolutely different world". He read Maths at the University of Pennsylvania, but abandoned that to study Music at New York University with Marion Bauer, seizing any opportunity to experience the music of Schoenberg, and meeting the composer on a couple of occasions. He also studied privately with Roger Sessions, a central figure for supporters of the anti-populism ideal in American music, and later followed Sessions to Princeton. During the early years of the Second World War he was involved in secret military intelligence in Washington before returning to Princeton to teach mathematics. There his PhD, entitled The Function of the Said Structure in the 12-Tone System, was rejected in 1946; it was finally awarded in 1992 with the university uneasily explaining that his work had been "too far ahead of its time". The headline on his infamous 1958 paper (published in High Fidelity magazine) haunted him for the rest of his life. It was, he insisted, not of his choosing. Nevertheless, it bore a true resemblance to its contents and Adams suspects that it was always Babbitt's "puckish intention" to offend the larger classical music community. Enthusiasts of Serialism in Europe championed his cause and British critics turned out to see what all the noise was about. Yet even Stanley Sadie, who advocated the creation of a national electronic studio, considered Ensembles for Synthesizer, performed at the Festival Hall in 1969, to be a "busy, garrulous piece [which] seemed unshapely, unclearly organised and its ending duly unpredictable". Recently the musicologist Harold Rosenbaum arranged for the publication and performance of a Mass that Babbitt had written many years ago. When the parts arrived he found the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus and Agnus Dei, but no Credo. Fearing it lost he telephoned the composer in embarrassment, only to be told: "My boy, I don't believe in Credos. I didn't write one." Among many US honours, Babbitt received a Pulitzer citation in 1982. Despite his prowess in electronic music, Babbitt shied away from later technology. "I don't have email; I'm not online in any respect. I am totally offline," he told an interviewer in 2001. His wife Sylvia, whom he married before the war, predeceased him in 2005. He is survived by a daughter. --The Telegraph Feb 1, 2011

|

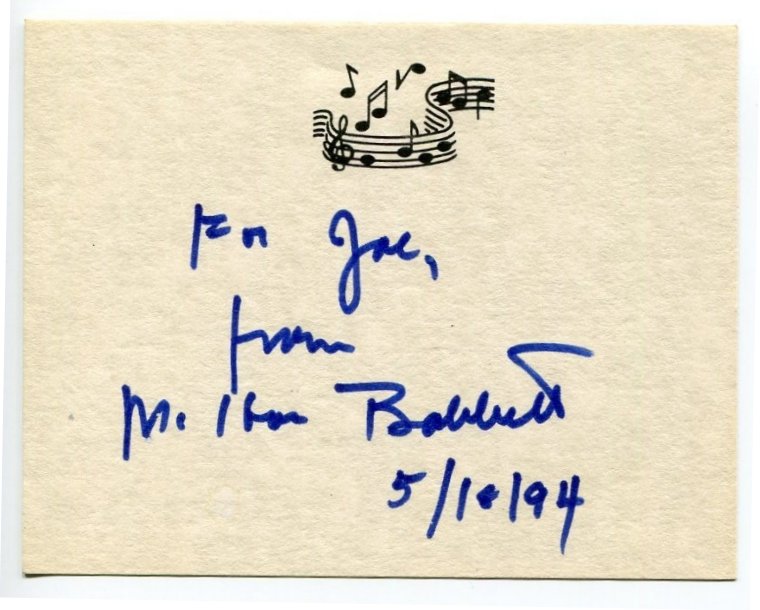

This interview was recorded in Chicago on November 6, 1987.

Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1991 and 1996. The transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.