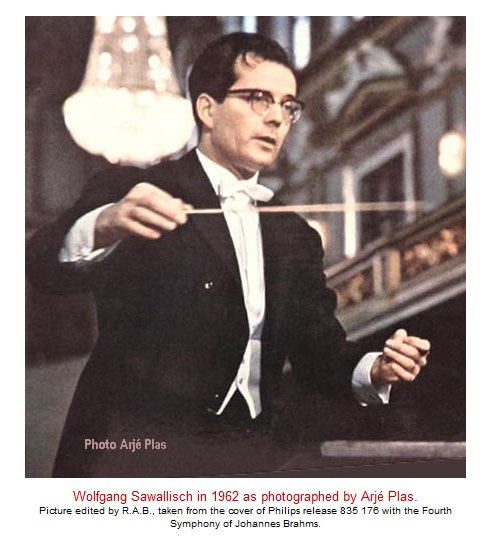

Wolfgang Sawallisch began to learn

the piano at the age of five, studying theory and composition while still

at school and subsequently becoming a pupil of Ruoff, Haas, and Sache in

Munich, prior to joining the German army in 1942. Following the end of World

War II he completed his musical studies at the Munich High School for Music.

He then joined the Augsburg Opera in 1947 as a répétiteur,

and with the violinist Gerhard Seitz won the first prize for duo performances

at the Geneva International Music Competition in 1949. Having made his début

as a conductor with Humperdinck’s Hänsel

und Gretel in 1950 at Augsburg, he shortly afterwards became first

conductor there. He was Germany’s youngest general music director on his

appointment to head the Aachen Opera in 1953, and was later recruited to

the same post at Wiesbaden in 1958 and at Cologne in 1960. He also taught

conducting at the Cologne Conservatory. Sawallisch conducted annually at

the Bayreuth Festival from 1957 to 1961, opening the 1957 Festival with Tristan und Isolde. In the same year

he made his English débuts as both an accompanist, with the soprano

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, and as a conductor, with her husband Walter Legge’s

Philharmonia Orchestra. Legge also engaged him to make several important

recordings, notably the first commercial release of Richard Strauss’s final

opera, Capriccio.

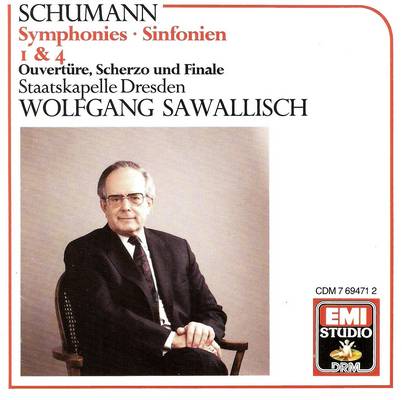

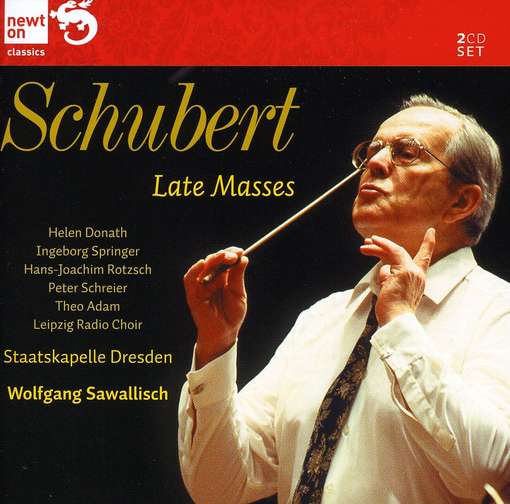

In 1960, in addition to his appointment at Cologne, Sawallisch became chief conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, and in 1961 of the Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra, retaining both positions until 1970 and touring America successfully with the Vienna Symphony in 1964. He succeeded Paul Kletzki as chief conductor of the Suisse Romande Orchestra in 1972, having been appointed the previous year as chief conductor of the Bavarian State Opera. He led this company on another successful tour, to London in 1972, and remained at its head until 1992, making numerous recordings, notably of lesser-known works by Wagner and Richard Strauss. Sawallisch is also a gifted pianist and has given recitals with many of the leading instrumentalists and singers of our time, including Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. In 1990, Sawallisch was named as the chief conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra in succession to Riccardo Muti, taking up this appointment in 1993. He relinquished the position in 2003 following the death of his wife, but continued to appear with the orchestra as a most-welcome guest. In addition to his permanent posts, Sawallisch has had an active career as a guest conductor with the world’s leading orchestras, including the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, London Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, and the Orchestre National de Radio France in Paris, and has conducted regularly at La Scala, Milan. He is especially popular in Japan, where he has appeared regularly with the NHK Symphony Orchestra. Sawallisch is a conservative, ‘no-nonsense’ conductor whose platform style is economical and clear. His interpretations are grounded firmly on a complete understanding of the Austro-German school of composers, of which he is a pre-eminent interpreter. His discography is large and distinguished, and includes recordings of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Wagner, Bruckner, Dvořák, Richard Strauss and Hindemith in both studio and live incarnations. |

Most of the interviews that I have done in the course of my radio career

were of my own selection. I would seek out various composers and performers

that interested me and present their words along with their music.

Sometimes, however, the desire for publicity on the part of venues or organizations

would cause them to ask for my time and effort. Usually I would jump

at the chance to meet another world-class musician, and this is one of those

happy occasions.

Most of the interviews that I have done in the course of my radio career

were of my own selection. I would seek out various composers and performers

that interested me and present their words along with their music.

Sometimes, however, the desire for publicity on the part of venues or organizations

would cause them to ask for my time and effort. Usually I would jump

at the chance to meet another world-class musician, and this is one of those

happy occasions. WS: Ja.

[Both laugh] I do it, but with greatest pleasure because it is such

a great orchestra. I love this orchestra and all the members.

They are so involved in music and they like to play music, and it makes every

hour together with this orchestra really a great, great satisfaction.

WS: Ja.

[Both laugh] I do it, but with greatest pleasure because it is such

a great orchestra. I love this orchestra and all the members.

They are so involved in music and they like to play music, and it makes every

hour together with this orchestra really a great, great satisfaction. BD: You don’t want it to be too mathematical?

BD: You don’t want it to be too mathematical? BD: Is it right to assume that even a virtuoso orchestra

should be capable of Mozart and Debussy and Bruckner and contemporary works?

BD: Is it right to assume that even a virtuoso orchestra

should be capable of Mozart and Debussy and Bruckner and contemporary works? WS: Yes! Next season, the ’94-’95 season,

I asked all my guest conductors to include Haydn symphonies in their programs,

and they did it with great pleasure! We will have between twelve and

fifteen different Haydn symphonies, from the very first one until the last

one. In the opening week I will conduct The Seasons, the great oratorio by Haydn,

for the first time in the history of the Philadelphia Orchestra! It’s

never been performed here. It also makes me very happy to have a cello

concerto, a piano concerto, and small symphonies, bigger symphonies and so

on. It gives a great advantage for the orchestra to work with different

conductors. Each conductor is certainly willing to bring a special

sound, and a special feeling and playing for the music of Haydn.

WS: Yes! Next season, the ’94-’95 season,

I asked all my guest conductors to include Haydn symphonies in their programs,

and they did it with great pleasure! We will have between twelve and

fifteen different Haydn symphonies, from the very first one until the last

one. In the opening week I will conduct The Seasons, the great oratorio by Haydn,

for the first time in the history of the Philadelphia Orchestra! It’s

never been performed here. It also makes me very happy to have a cello

concerto, a piano concerto, and small symphonies, bigger symphonies and so

on. It gives a great advantage for the orchestra to work with different

conductors. Each conductor is certainly willing to bring a special

sound, and a special feeling and playing for the music of Haydn. WS: Of course each of these conductors has his own

feeling about interpretation and styles. After a long experience, I

have some connections to great late conductors. I was always a great

admirer of Bruno Walter, of Klemperer, and for both opera and concert performances

of Wilhelm Furtwängler. I adored Hans Knappertsbusch in Munich

when I was a young boy, and I listened to all the performances Hans Knappertsbusch

conducted in Munich. I was a great admirer of Clemens Krauss, and I

learned a lot of Strauss interpretation from him and from Karl Böhm.

All these great examples of the past have influenced my own feeling about

music and interpretations, especially the direction of operas by Wagner, Mozart,

and Strauss, and even in the interpretation of the great symphonic music

by Schubert, Schumann, Beethoven and Brahms, and so on.

WS: Of course each of these conductors has his own

feeling about interpretation and styles. After a long experience, I

have some connections to great late conductors. I was always a great

admirer of Bruno Walter, of Klemperer, and for both opera and concert performances

of Wilhelm Furtwängler. I adored Hans Knappertsbusch in Munich

when I was a young boy, and I listened to all the performances Hans Knappertsbusch

conducted in Munich. I was a great admirer of Clemens Krauss, and I

learned a lot of Strauss interpretation from him and from Karl Böhm.

All these great examples of the past have influenced my own feeling about

music and interpretations, especially the direction of operas by Wagner, Mozart,

and Strauss, and even in the interpretation of the great symphonic music

by Schubert, Schumann, Beethoven and Brahms, and so on.

This interview was recorded on the telephone on May 2,

1994. Sections were used (along with recordings) on

WNIB five days later, and again in 1998. It was transcribed

and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.