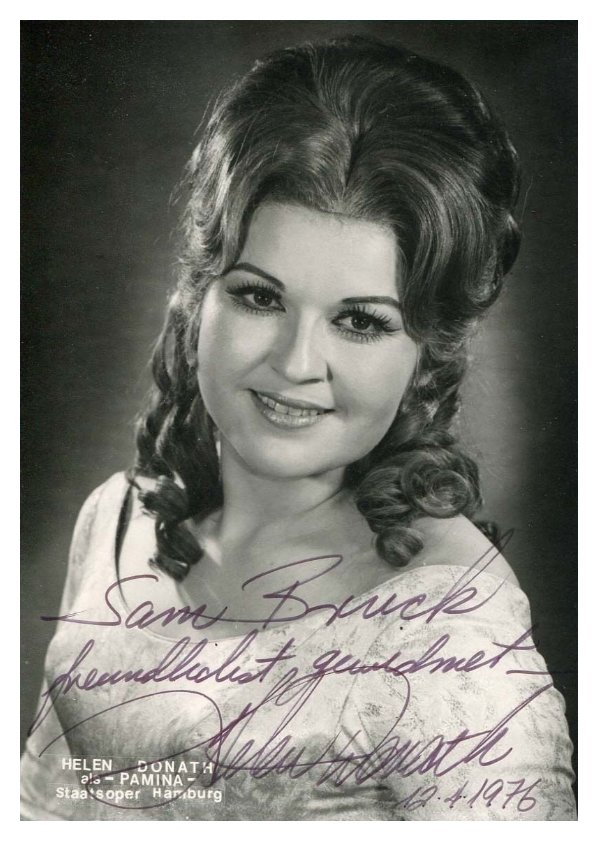

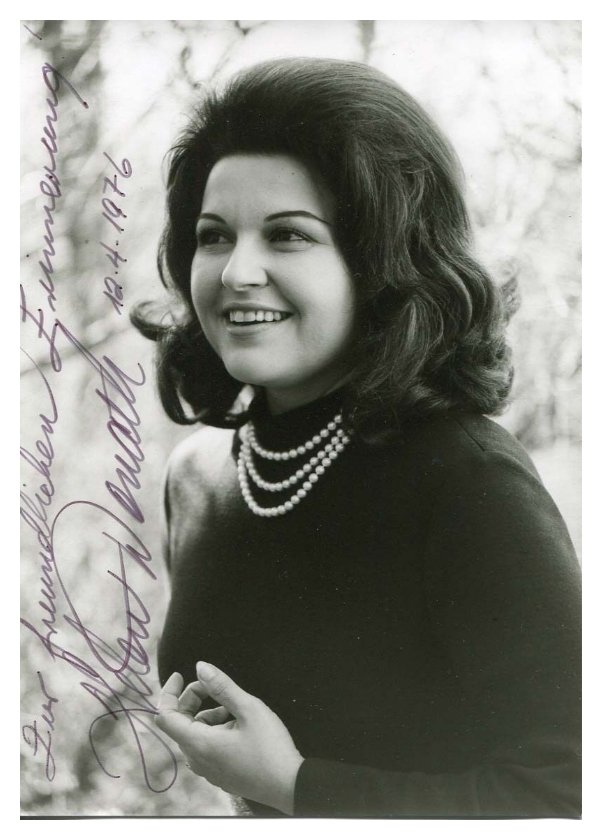

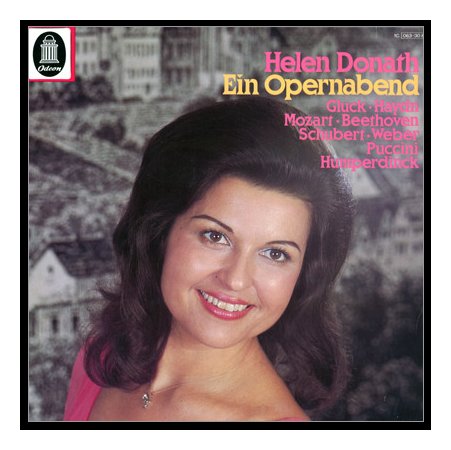

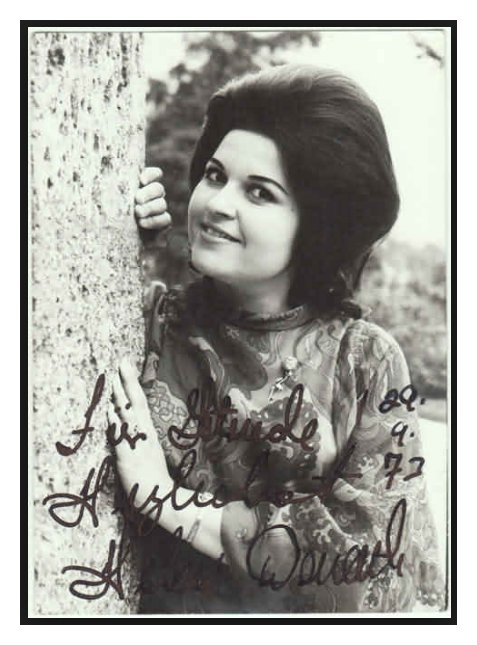

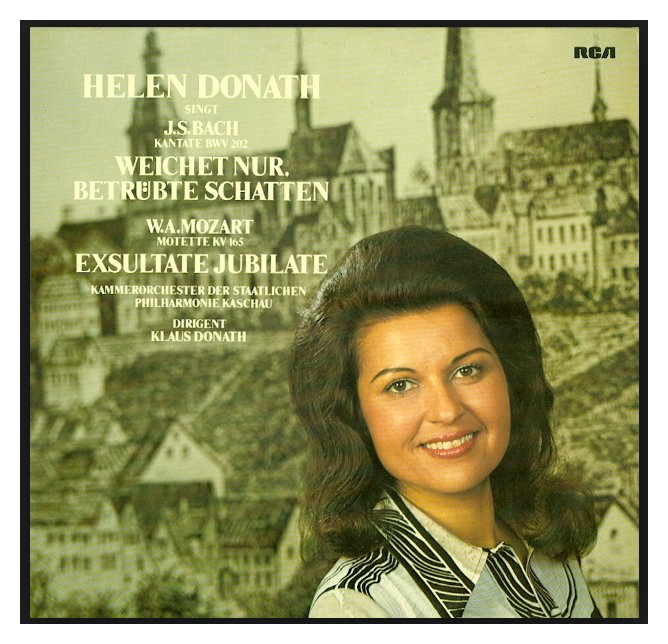

| Helen Donath (born July 10, 1940)

is one of the greatly admired lyric sopranos of her age, noted for her pure

timbre and interpretive powers, as well as her vocal longevity. She is equally

adept on the opera stage, in recital, and in oratorios. Like many singers

of her generation, she fell in love with opera through the Mario Lanza movie

The Great Caruso. She first

studied music at Del Mar College in her hometown of Corpus Christi at the

age of 14 and later in New York with Paola Novikova, where she made her

concert debut in 1958. After auditioning for an agent who sent her to the

Cologne Opera, she made her opera stage debut in 1962 in the comprimario

role of Inez in Verdi's Il Trovatore.

In 1966, she joined the Munich Staatsoper as a guest artist, beginning a

long association with that house. During the 1960s, she also briefly became

a protégé of Herbert von Karajan, but her persistent refusal

of his offers of roles she thought were too heavy brought that rapport to

an end. She was to have made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1968, but canceled

because of her later pregnancy; she didn't appear at the Met until 1991.

In 1970, she made her Salzburg Festival debut as Pamina in Mozart's The Magic Flute. Her United States opera

debut was in 1971 as Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier.

In 1979, she first appeared at Covent Garden as Anne in Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress. Until her return

to the United States in the early '90s, the majority of her career took

place in Germany and Austria, and she was awarded the title of Kammersaengerin.

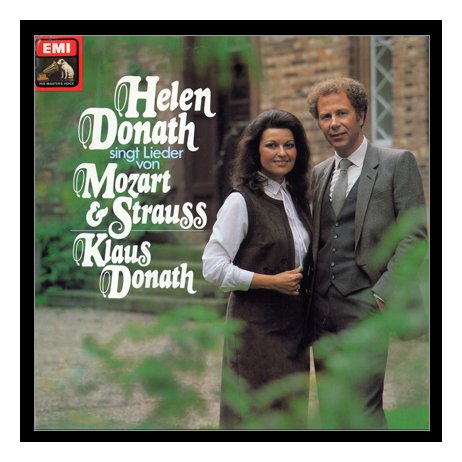

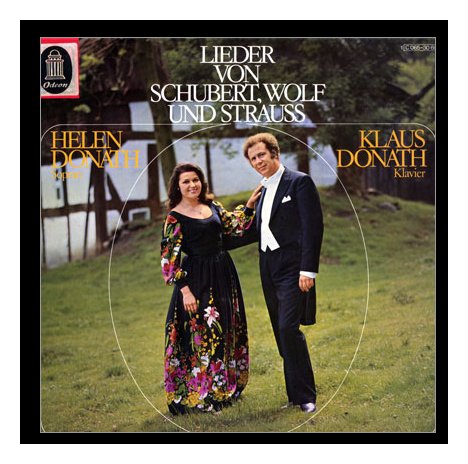

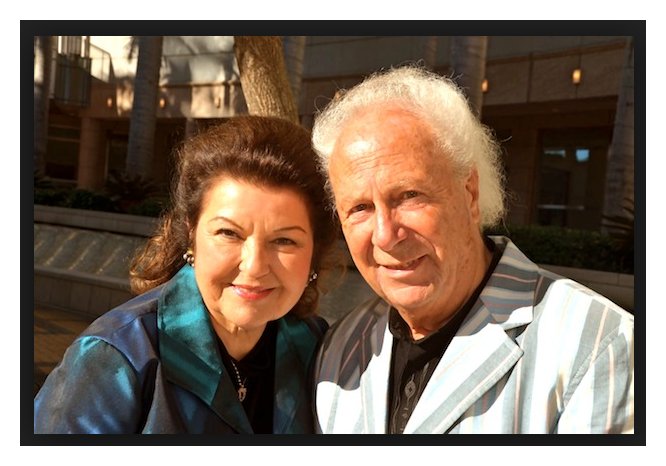

Her husband, who has also acted as her vocal advisor, is pianist, choir

director, and conductor Klaus Donath. Their son, Alexander, is a stage director.

|

Bruce Duffie: With so much singing all over the

world already, are you happy to still be going strong?

Bruce Duffie: With so much singing all over the

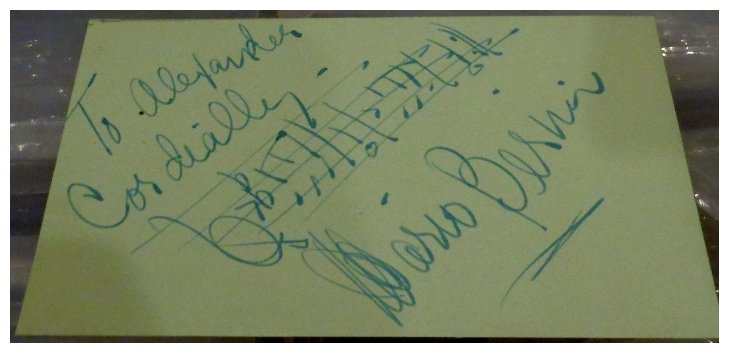

world already, are you happy to still be going strong? | [Obituary for Mario Berini, published

in The New York Times, March 11,

1993] Mario Berini, an opera singer known for his interpretation of dramatic tenor roles, died on Monday at Beth Israel Hospital. He was 80 and lived in Manhattan. His wife, Anna Lee, said he had been ill for some time. Mr. Berini sang Cavaradossi in "Tosca" in February 1944 in the first opera performance at City Center. Two years later he made his debut with the Metropolitan Opera, taking over the title role in "Faust" with just nine hours' notice when the scheduled tenor, Raoul Jobin, became ill. In his two seasons with the Met he appeared as Don Jose in "Carmen," Dimitri in "Boris Godunov" and other roles. He sang Rodolfo in "La Boheme" and the title role in "Tales of Hoffmann" with other companies, and also appeared on Broadway in 1946 in Ben Hecht's play "A Flag Is Born." Mr. Berini was born in Russia and grew up in California. He made his New York debut in 1940 with the San Carlo Opera Company and later sang with major opera companies and orchestras in the United States. He also sang at Radio City Music Hall and on radio and television. In the early 1950's, one of his vocal cords was severed during surgery for removal of a node. With his singing career over, he turned to teaching. Among his students were the soprano Helen Donath and the cabaret singer Pia Zadora. In addition to his wife, he is survived by a sister, Lynn Holzman of Los Angeles, and a brother, Alan Edwards of San Francisco.

|

HD: Oh, absolutely. In every respect, be

true to yourself. Try to be honest in all things, and also try to be

loving and giving. But the thing is to be honest, because if you lie,

you’re not comfortable with yourself. There are many things that I could

have done. I could have put on a show, I could have done this, I could

have done that. I could be a naughty person or I could be a very demanding

person, and if that were in my nature, then I would be true to myself.

But that’s not in my nature. Then I would have to lie to myself, and

I have to live with myself. It is so important that you like yourself.

That was perhaps the biggest trial for me because I always had inferiority

complexes, thinking everybody else is better and everybody else is more beautiful,

and I’m never going to get married because I’m not pretty enough for anybody,

and I will never have children because I’ll be a disastrous mother.

God was good to me and sent me this absolutely marvelous husband. Our

anniversary is on 10 July, my birthday, and we will be married twenty-seven

years. We already had our silver wedding anniversary behind us, and

we have an absolutely magnificent young son, who’s just had his twenty-fourth

birthday on 11 June. That’s Richard Strauss’s birthday. My birthday

is with Carl Orff, and Klaus’s birthday is two days before Beethoven.

So we’re a very musical family. Our son, Alexander, is a director!

He is the assistant director in East Berlin of Harry Kupfer. Alexander

had done Carmen and Così Fan Tutte...

HD: Oh, absolutely. In every respect, be

true to yourself. Try to be honest in all things, and also try to be

loving and giving. But the thing is to be honest, because if you lie,

you’re not comfortable with yourself. There are many things that I could

have done. I could have put on a show, I could have done this, I could

have done that. I could be a naughty person or I could be a very demanding

person, and if that were in my nature, then I would be true to myself.

But that’s not in my nature. Then I would have to lie to myself, and

I have to live with myself. It is so important that you like yourself.

That was perhaps the biggest trial for me because I always had inferiority

complexes, thinking everybody else is better and everybody else is more beautiful,

and I’m never going to get married because I’m not pretty enough for anybody,

and I will never have children because I’ll be a disastrous mother.

God was good to me and sent me this absolutely marvelous husband. Our

anniversary is on 10 July, my birthday, and we will be married twenty-seven

years. We already had our silver wedding anniversary behind us, and

we have an absolutely magnificent young son, who’s just had his twenty-fourth

birthday on 11 June. That’s Richard Strauss’s birthday. My birthday

is with Carl Orff, and Klaus’s birthday is two days before Beethoven.

So we’re a very musical family. Our son, Alexander, is a director!

He is the assistant director in East Berlin of Harry Kupfer. Alexander

had done Carmen and Così Fan Tutte... BD: Are there some solo recitals as well as major

works?

BD: Are there some solo recitals as well as major

works?

BD: So in all of these characters, you have

to do a lot of research into when they lived and how they would really react?

BD: So in all of these characters, you have

to do a lot of research into when they lived and how they would really react? HD: Absolutely, I become the character.

It’s very important for me to do so. There are things that I cannot

do because I cannot slip into the character. There are parts that I’ve

been asked to sing and then I look at them – for instance Pasquale. I cannot sing Pasquale because it doesn’t really ring

true for me. People say that she’s lying, and I don’t like to lie.

I can’t stand up on a stage and lie to people. For someone who is

actress enough to be able to slip into that and do it, that’s absolutely

correct and fine and wonderful. Strangely enough – though I’ve never

tried it – something like Salome would be easier for me to do than Pasquale. That girl was wacky,

but in Pasquale she’s mean to him,

and I don’t like to be mean. Salome is not very nice for chopping

Johannes’ head off. I mean, please don’t get me wrong. I think

she’s a psycho and that makes a different situation.

HD: Absolutely, I become the character.

It’s very important for me to do so. There are things that I cannot

do because I cannot slip into the character. There are parts that I’ve

been asked to sing and then I look at them – for instance Pasquale. I cannot sing Pasquale because it doesn’t really ring

true for me. People say that she’s lying, and I don’t like to lie.

I can’t stand up on a stage and lie to people. For someone who is

actress enough to be able to slip into that and do it, that’s absolutely

correct and fine and wonderful. Strangely enough – though I’ve never

tried it – something like Salome would be easier for me to do than Pasquale. That girl was wacky,

but in Pasquale she’s mean to him,

and I don’t like to be mean. Salome is not very nice for chopping

Johannes’ head off. I mean, please don’t get me wrong. I think

she’s a psycho and that makes a different situation. HD: That’s a little bit of a tricky question.

If your technique is really fundamental, your voice will always

adjust itself to the room. It has something to do with

the way that I have been taught. I had wonderful teachers ever since

I started voice lessons when I was fourteen. Then when I was

twenty, I had the teacher of my voice teacher, and he was a catastrophe.

But that was wonderful because at a very young age I learnt how not to sing.

Then I looked desperately and found Mario Berini, and he put me back on

the track within six or eight weeks. [Demonstrates a humming exercise

on three notes up and down] That’s all we did. At the beginning

it was not even functioning. The vocal cords were swollen and wouldn’t

close any more. It was terrible.

I thought really I had lost my voice, and he helped me get it back.

Then I went to Germany and met George London’s teacher, Paola Novikova.

[Novikova (1896-1967) was Russian-born

coloratura soprano who studied in Germany, and in Italy with Mattia Battistini.]

She was also the teacher of Nicolai Gedda, Kim Borg, Hilde Gueden, Hilde

Zadek, Erich Kunz... it’s a humungous list. She gave me the real mask,

and that was the technique I used for many years. Then about ten years

ago, a former colleague of mine was talking to me in Munich, and she said

there’s so much more I could do with my voice. I am always all ears

for everything, and she showed me exactly what to add to what Novikova had

taught me. With just that little zip, more has just opened up all sort

of dimensions for my musical and vocal career, which is wonderful.

People told me when I sang at the Met that it was astounding to hear my

voice through all of house. I don’t think I’d be able to pull that

off with because this is a really a humungous place. When I do Ännchen,

people say they hear my voice over the whole thing, over the whole shebang!

It’s not because I want it that way but it’s just because I try to reach

out and touch someone with it.

HD: That’s a little bit of a tricky question.

If your technique is really fundamental, your voice will always

adjust itself to the room. It has something to do with

the way that I have been taught. I had wonderful teachers ever since

I started voice lessons when I was fourteen. Then when I was

twenty, I had the teacher of my voice teacher, and he was a catastrophe.

But that was wonderful because at a very young age I learnt how not to sing.

Then I looked desperately and found Mario Berini, and he put me back on

the track within six or eight weeks. [Demonstrates a humming exercise

on three notes up and down] That’s all we did. At the beginning

it was not even functioning. The vocal cords were swollen and wouldn’t

close any more. It was terrible.

I thought really I had lost my voice, and he helped me get it back.

Then I went to Germany and met George London’s teacher, Paola Novikova.

[Novikova (1896-1967) was Russian-born

coloratura soprano who studied in Germany, and in Italy with Mattia Battistini.]

She was also the teacher of Nicolai Gedda, Kim Borg, Hilde Gueden, Hilde

Zadek, Erich Kunz... it’s a humungous list. She gave me the real mask,

and that was the technique I used for many years. Then about ten years

ago, a former colleague of mine was talking to me in Munich, and she said

there’s so much more I could do with my voice. I am always all ears

for everything, and she showed me exactly what to add to what Novikova had

taught me. With just that little zip, more has just opened up all sort

of dimensions for my musical and vocal career, which is wonderful.

People told me when I sang at the Met that it was astounding to hear my

voice through all of house. I don’t think I’d be able to pull that

off with because this is a really a humungous place. When I do Ännchen,

people say they hear my voice over the whole thing, over the whole shebang!

It’s not because I want it that way but it’s just because I try to reach

out and touch someone with it.

|

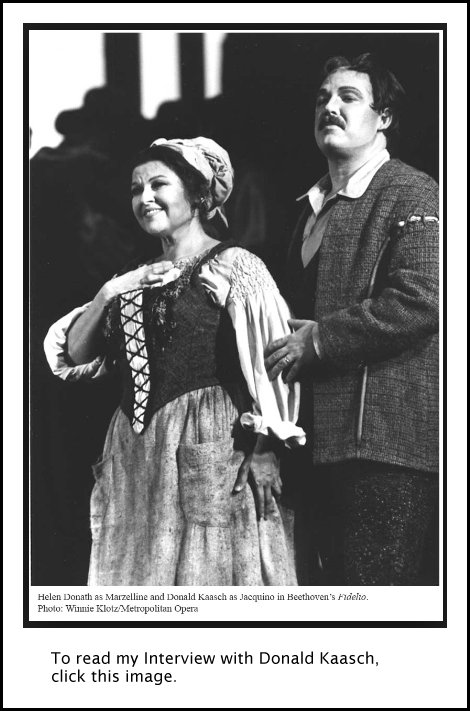

Besides the solo recitals and

the recordings she mentions in the interview,

here are some of the other recordings Donath has made over the years . . . . . [Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. They are only linked once - repeated appearances do not have the link. Those who are linked in the text above are also not linked in this chart.] Sancta

Susanna (Hindemith) Berlin Radio Symphony/Gerd Albrecht [Wergo]

Das Christelflein (Pfitzner) with Perry, Ahnsjö, Malta; Munich Radio Orchestra/Kurt Eichorn [Orfeo D'Or] Paulus (Mendelssohn) with Fischer-Dieskau, Schwarz, Hollweg; Dusseldorf Sym/Frübeck de Burgos [Angel] Merry Wives of Windsor (Nicolai) with Mathis, Schwarz, Moll, Schreier, Weikl; Berlin State Orch/Klee [DG] Königskinder (Humperdinck) with Schwarz, Dallapozza, Prey, Ridderbusch; Munich Radio Orch/Wallberg [EMI] Seasons (Haydn) with Adalbert Kraus, Widmer; Ludwigsburg Orch/Gönnenwein [Vox] Don Giovanni (Mozart) with Soyer, Evans, Harper, Sgourda, Alva; English Chamber Orch/Barenboim [EMI] Requiem (Mozart) with Minton, Davies, Nienstedt; BBC Sym/Davis [Phi] Land of Smiles (Lehar) with Jerusalem, Lindner, Finke, Hirte; Munich Radio Orch, Boskovsky [EMI] Meistersinger (Wagner) with Adam, Kollo, Hesse, Evans, Schreier, Ridderbusch, Kélémen; Drsden State Orch/Karajan [EMI] Hansel and Gretel (Humperdinck) with Moffo, Fischer-Dieskau, Berthold, Auger, Ludwig; Munich Radio Orch/Eichorn [Eurodisc] Mass in B Minor (Bach) with Fassbaender, Ahnsjö, Hermann, Holl; Bavarian Radio Orch/Jochum [EMI] Masked Ball (Verdi) with Tebaldi, Pavarotti, Milnes, Resnik, Van Dam; St. Cecilia Orch/Bartoletti [London] Alexander's Feast (Handel) with Tear, Allen, Burgess; English Chamber Orch /Ledger [Angel] Freischütz (Weber) with Behrens, Meven, Kollo, Moll, Brendel; Bavarian Radio Orch/Kubelik [London] Messiah (Handel) with Reynolds, Burrows, McIntyre; London Phil/Richter [DG] Evangelimann (Kienzl) with Jerusalem, Hermann, Wenkel, Moll; Munich Radio Orch/Zagrosek [EMI] Symphony #2 (Mendelssohn); with Hansmann, Kmentt; New Phil/Sawallisch [Phi] Magic Flute (Mozart) with Schreier, Geszty, Adam, Leib, Hoff, Neukirch; Dresden State Orch/Suitner [RCA] Turn of the Screw (Britten) with Harper, Tear, June; Covent Garden Orch/Davis [Decca] Merry Widow (Lehar) with Moser, Prey, Jereusalem, Kusche; Munich Radio Orch/Wallberg [EMI] Leonore (Beethoven) with Moser, Cassilly, Adam, Ridderbusch; Dresden State Orch/Blomstedt [EMI] Fidelio (Beethoven) with Dernesch, Vickers, Kélémmen, Ridderbusch, Van Dam; Berlin Phil/Karajan [EMI] Orfeo (Haydn) with Swensen, Greenberg, Quasthoff; Munich Radio Orch/Hager [Orfeo (!)] Rose Pilgerfahrt (Schumann) with Hamari, Altmeyer, Sotin; Dusseldorf Sym/Frübeck de Burgos [EMI] Christmas Oratorio (Bach) with Lipovšek, Schreier, Büchner, Holl; Dresden State Orch/Schreier [Phi] Creation (Haydn) with Tear, Van Dam; Philh/Frübeck de Burgos [EMI] Marriage of Figaro (Mozart) with Titus, Varady, Furlanetto, Schmiege, Zednik, Nimsgern; Bavarian Radio Sym/Davis [RCA] Missa Solemnis (Beethoven) with Soffel, Jerusalem, Sotin; London Phil/Solti [BBC] Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) with Horne, Lorengar; Covent Garden Orch/Solti [Decca] Palestrina (Pfitzner) with Gedda, Fischer-Dieskau, Weikl, Ridderbusch, Fassbaender; Bavarian Radio Orch/Kubelik [DG] Rosenkavalier (Strauss) with Crespin, Minton, Jungwirth, Wiener, Dickie, Howells, Pavarotti; Vienna Phil/Solti [Decca] Carmen (Bizet) with Moffo, Corelli, Cappuccilli, Auger, Van Dam; Berlin German Opera Orch/Maazel [RCA] Requiem (Mozart) with Ludwig, Tear, Lloyd; Philh/Giulini [EMI] Vera Costanza (Haydn) with Norman, Ahnsjö, Ganzarolli, Trimarchi; Lausanne Chamber Orch/Dorati [Phi] Gianni Schicchi (Puccini) with Panerai, Seiffert; Munich Radio Orch/Patané [Eurodisc] L'Incoronazione di Poppea (Monteverdi) with Söderström, Berberian, Equiluz, Esswood, Langridge; Vienna Concentus Musicus/Harnoncourt [Teldec] Gärtnerin aus Liebe (Mozart) with Norman, Troyanos, Cotrubas, Unger, Hollweg, Prey; North German Radio Orch/Schmidt-Isserstedt [Phi] Finta Semplice (Mozart) with Holl, Rolfe Johnson, Berganza, Ihloff, Thomas Moser, Lloyd; Salzburg Mozarteum Orch/Hager [Orfeo] Mass in A-Flat (Schubert) with Fassbaender, Araiza, Fischer-Dieskau; Bavarian Radio Orch/Sawallisch [EMI] Symphony #9 (Beethoven) with Soffel, Jerusalem, Lika; Munich Phil/Celibidache [EMI] Elijah (Mendelssohn) with Miles, van Nes, George, Klein; Israel Phil/Masur [Teldec] Apollo e Daphne (Handel) with Runge; Cappella Coloniensis/Wich [Phoenix] Symphony #9 (Beethoven) with Schmidt, König, Estes; Bavarian Radio Orch/Davis [Phi] Ludio Silla (Mozart) with Schreier, Auger, Varady, Mathis, Krenn; Salzburg Mozarteum Orch/Hager [Phi]

|

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel in Northbrook, IL (a suburb of Chicago, near the Ravinia Festival) on June 18, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995, 1997 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.