BD: So then, the conductor’s job really has metamorphosed

from being a dictator to being an interrogator?

BD: So then, the conductor’s job really has metamorphosed

from being a dictator to being an interrogator? BD: Is that still going on?

BD: Is that still going on? DA: I’d say in the last fifteen years, definitely.

In the beginning, it was hard, because, since I was, as Bob Dylan said in

his great song, “Like a rolling stone.” I was what they would call

a complete unknown! [Both laugh] Sometimes I noticed that I would

have the complete unknown amount of rehearsal time, which was for a fifteen-minute

piece they would spend sixteen minutes rehearsing it. [Both laugh]

They’d run through it once and then they’d say, “Well, we don’t have any

more time for this piece by Mr., ah, Ammanreenz, what’s your name there,

son?” But at any rate, at least the people were

kind enough to play it, so they would say to the orchestra, “Watch me in

the place here where we fell apart. Just remember that it gets slower

here and faster there,” and that would be it. Then they’d perform the

piece. I was lucky to even have anybody look at it and perform it,

but at the same time, it was what they very often would refer to as a perfunctory

reading. Then when I got a little better known, and after I became

the first composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, back twenty

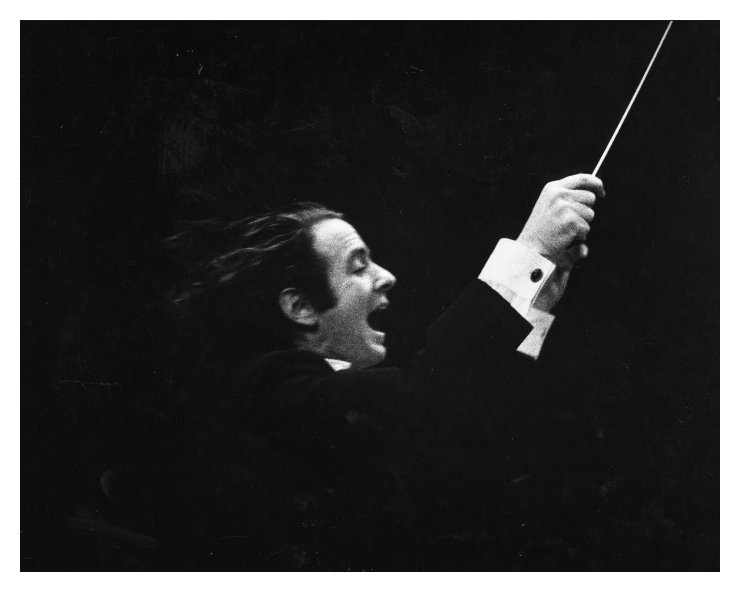

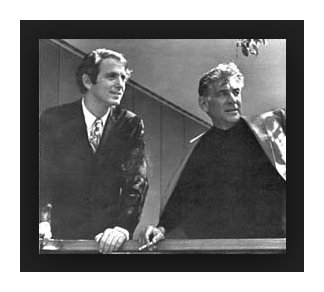

years ago now, in the1966-67 season [see

photo at left with Leonard Bernstein], then some other people, thank

heavens, began to look at some of my music. When they decided to perform

some of the pieces, they would actually study it a little beforehand, and

also have some rehearsal time so that the orchestra or the singers or the

performers would have a chance to rehearse it. One of the things that

we learn as composers is that in orchestral music, if you write a piece

that requires an enormous amount of rehearsal, the chances are that the piece

won’t get performed that much. So we have to learn how to achieve the

same interesting ideas without making impossible obstacles for performance.

The piece I wrote for the Philadelphia Orchestra, which was written in 1977,

although there’s a lot of very complicated music in that, I was able to figure

a way of writing so that it was simple enough in terms of the basic structure

that it didn’t require that much rehearsal time, thank heavens. Even

though it’s a long piece, I found that orchestras can rehearse a twenty-eight

minute piece, go through it twice and be ready to perform it. The piece

that I wrote for the Kansas City Symphony, an overture called Across the Wide Missouri, which they

commissioned and which is played a lot now — when we did it here at Grant

Park, we went through it twice and it was ready to perform. With the

Toronto Symphony, Montreal Symphony, other orchestras I’ve conducted, really

excellent orchestras, I’ve found if they can play through the piece twice,

I can make a few comments and they can do it. It has a lot of tricky,

complicated rhythms and things in it, but I was able to figure a way of doing

that and notating it and putting it in a simple, rhythmical context, so that

all the syncopations and counter-rhythms and poly-rhythms and things that

jump all over the place aren’t that hard for the individual players to figure

out how to fit together.

DA: I’d say in the last fifteen years, definitely.

In the beginning, it was hard, because, since I was, as Bob Dylan said in

his great song, “Like a rolling stone.” I was what they would call

a complete unknown! [Both laugh] Sometimes I noticed that I would

have the complete unknown amount of rehearsal time, which was for a fifteen-minute

piece they would spend sixteen minutes rehearsing it. [Both laugh]

They’d run through it once and then they’d say, “Well, we don’t have any

more time for this piece by Mr., ah, Ammanreenz, what’s your name there,

son?” But at any rate, at least the people were

kind enough to play it, so they would say to the orchestra, “Watch me in

the place here where we fell apart. Just remember that it gets slower

here and faster there,” and that would be it. Then they’d perform the

piece. I was lucky to even have anybody look at it and perform it,

but at the same time, it was what they very often would refer to as a perfunctory

reading. Then when I got a little better known, and after I became

the first composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, back twenty

years ago now, in the1966-67 season [see

photo at left with Leonard Bernstein], then some other people, thank

heavens, began to look at some of my music. When they decided to perform

some of the pieces, they would actually study it a little beforehand, and

also have some rehearsal time so that the orchestra or the singers or the

performers would have a chance to rehearse it. One of the things that

we learn as composers is that in orchestral music, if you write a piece

that requires an enormous amount of rehearsal, the chances are that the piece

won’t get performed that much. So we have to learn how to achieve the

same interesting ideas without making impossible obstacles for performance.

The piece I wrote for the Philadelphia Orchestra, which was written in 1977,

although there’s a lot of very complicated music in that, I was able to figure

a way of writing so that it was simple enough in terms of the basic structure

that it didn’t require that much rehearsal time, thank heavens. Even

though it’s a long piece, I found that orchestras can rehearse a twenty-eight

minute piece, go through it twice and be ready to perform it. The piece

that I wrote for the Kansas City Symphony, an overture called Across the Wide Missouri, which they

commissioned and which is played a lot now — when we did it here at Grant

Park, we went through it twice and it was ready to perform. With the

Toronto Symphony, Montreal Symphony, other orchestras I’ve conducted, really

excellent orchestras, I’ve found if they can play through the piece twice,

I can make a few comments and they can do it. It has a lot of tricky,

complicated rhythms and things in it, but I was able to figure a way of doing

that and notating it and putting it in a simple, rhythmical context, so that

all the syncopations and counter-rhythms and poly-rhythms and things that

jump all over the place aren’t that hard for the individual players to figure

out how to fit together. BD: From your point of view, what has been the impact

of this explosion of recordings?

BD: From your point of view, what has been the impact

of this explosion of recordings? BD: Now, what should be the other opera? Should

it be another one by David Amram? Should it be another contemporary

work? Or should it be, maybe, an old intermezzo or something like that?

BD: Now, what should be the other opera? Should

it be another one by David Amram? Should it be another contemporary

work? Or should it be, maybe, an old intermezzo or something like that?|

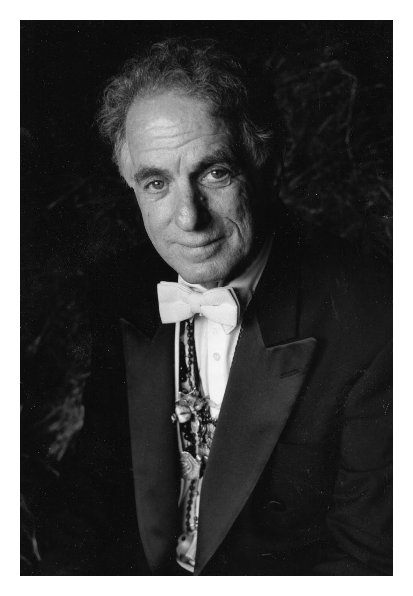

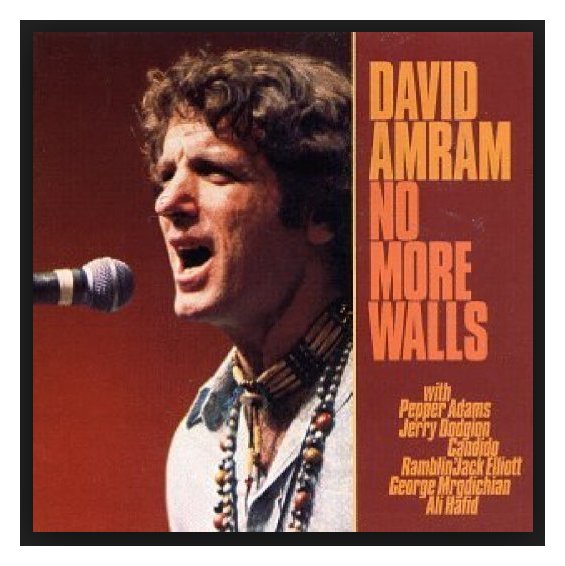

David Amram

“I can be high all the time on life...Anyone who expects me to be an introspective cosmic sourpuss to prove I’m a serious composer had better forget it!” warns the famously irreverent composer, conductor, and multi-instrumentalist David Amram. “I couldn’t care less if I’m gifted or not. I never tried to prove anything by writing music.” One of the most eclectic, versatile, and unpredictable American musicians of the 20th–21st centuries, Amram has given equal attention throughout his life thus far to contemporary classical art music, ethnic folk music, film and theater music, and jazz. The Boston Globe has saluted him as “the Renaissance man of American music,” and The New York Times noted that he was “multicultural before multiculturalism existed.” Yet Amram’s so-called multiculturalism has not been political—“correct” or otherwise—but rather a function of his genuine interest in a variety of musical traditions and practices. “Music is one world,” he has declared. Amram was born in Philadelphia, but he spent his childhood on the family farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where they moved shortly before his seventh birthday. His father had been a farmer before becoming a lawyer, and—like David Amram to this day—he continued to farm in addition to his professional pursuits. Since there was little Jewish population in that farming region, young David grew up without the benefit of a Jewish community, but his grandfather (David Werner Amram, for whom he was named), who had been active in early American Zionist circles and had spent considerable time on a kibbutz in Palestine, taught him basic Hebrew; and his father conducted Sabbath services in their home. His father also introduced him to recordings of cantorial music and to his own amateur piano renditions of European classical pieces. His uncle was a devotee of jazz, introducing David to recordings of such artists as Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong—and then taking him to hear some of those performers in person. Those three traditions—jazz, classical, and Jewish liturgical music—were thus somehow interrelated for him from childhood, in terms of both emotional and improvisational aspects. Amram began piano lessons at the age of seven. He experimented with trumpet and tuba before settling on the French horn as his principal instrument. By the age of sixteen he had also established a firm interest in composition. In 1948, he spent a year at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, but he temporarily abandoned formal musical education, earning his bachelor’s degree in European history from George Washington University in 1952. During those university years he was an extra horn player with the National Symphony, and he also studied privately with two orchestral members. He played for about a year in a chamber ensemble that performed both jazz and classical music—very unusual at that time—which contributed to his growing conviction that the two genres could reinforce each other. During his military service (1952–54) Amram was stationed in Europe and played with the Seventh Army Symphony, after which he toured for the State Department, playing chamber music. In Paris for a year, he devoted himself earnestly to composition and also played with jazz groups—including Lionel Hampton’s band—and he fraternized with Paris Review circles and such writers as George Plimpton and Terry Southern. In 1955, he returned to the United States, having resolved to focus more rigorously on fine-tuning his classical composition crafts. He attended the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied composition with Vittorio Giannini and Gunther Schuller and conducting with Dimitri Mitropoulos, and he also played in the Manhattan Woodwind Quintet. He supported himself by playing with such prominent jazz musicians as Charles Mingus at Café Bohemia and Oscar Pettiford at Birdland, and he led his own modern jazz group at the Five Spot Café on the Bowery. In 1956, Amram began a long association with producer Joseph Papp of the New York Shakespeare Festival, eventually composing scores for twenty-five of its Shakespeare productions. He and Papp collaborated on a comic opera, Twelfth Night, for which Papp adapted a libretto from the original play. Music for theater, film, and television has played a prominent role in Amram’s overall work. He wrote the incidental music for the Archibald MacLeish drama J.B., which won a Pulitzer Prize. He also wrote music for the American production of Camus’s Caligula; T.S. Eliot’s The Family Reunion; Eugene O’Neill’s Great God Brown; and Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. In 1959, he wrote music for—as well as acted in—Pull My Daisy, an experimental documentary film created and narrated by Jack Kerouac and featuring other Beat Generation writers, including Allen Ginsberg. He became even more widely known for his memorable scores for two of the most successful American films of the early 1960s, Splendor in the Grass and The Manchurian Candidate, and he also wrote the score for The Young Savages. His music for television includes a 1959 NBC dramatization of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, which starred Ingrid Bergman. That same year, his concert piece Autobiography for strings was presented under the auspices of New York University. During the 1966–67 season he was appointed by Leonard Bernstein as the first participant in the new composer-in-residence program at the New York Philharmonic. Amram has written more than one hundred orchestral and chamber works, a number of which have Judaically related themes. In a 2001 interview for Moment magazine, he expanded on his artistically driven concern for Jewish roots: I couldn’t be comfortable with people from every race and nationality if I didn’t have an innate sense of my own roots. If people ask you who you are and what your roots are, and you don’t have the same sense of wonder and desire to understand [being Jewish] as you do that of the people you’re with at the moment—if you don’t know and respect who you are, then others instinctively will doubt your ability to know and respect who they are. In addition to the music recorded by the Milken Archive, Amram’s Judaically related pieces include a movement of his Kokopelli symphony that is based on an old Hebraic chant; and his six-movement cantata, Let Us Remember (which he calls a “musical sermon”), to words of Langston Hughes, premiered at the 48th annual convention of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in San Francisco in 1965. Let Us Remember derives a universal message from the Jewish yizkor (memorial) liturgy, tying the American black freedom struggles to historical oppression of Jews and addressing the two peoples’ experience confronting hatred. In 1982, Amram became the director of the International Jewish Arts Festival, held annually on Long Island. Amram’s fascination with jazz was heightened when he first heard the voice of the famous cantor Yossele [Joseph] Rosenblatt on the soundtrack of Al Jolson’s film The Jazz Singer (generally cited as the first commercial “talking” picture). “When I heard that,” he recalled in a 1998 Milken Archive oral history interview on Ellis Island, “I was able to connect improvisation to that soulful, wailing sound.” When he was only twelve, he sat in as trumpeter with Luis Brown’s Negro Dixieland Band. He has always maintained that his earliest experiences with jazz changed his life. “It made me think of all composition as improvisation.” Later, his David Amram Jazz Quintet became a fixture in New York circles and clubs, and it appeared frequently at the Village Gate in Greenwich Village—one of the city’s most prestigious jazz, blues, and folk venues. He is fond of recalling that many of the great jazz musicians with whom he worked loved classical music and were fascinated by it. He was introduced to the music of Frederick Delius by Charlie Parker, who also transmitted his love of Bartók; and he remembers that Dizzie Gillespie’s favorite classical composers were Stravinsky and Bach. In 1970, he performed at the first International Jazz Festival in Dakar, Senegal, and, in 1977, he visited Cuba with Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, and Earl Hines. His piece, En Memoria de Chano Pozo, salutes the great Cuban drummer who played in Gillespie’s band in the late 1940s. Long before it was fashionable, Amram developed an interest in authentic ethnic music and native musical cultures. His visit to Brazil in 1969 left a profound stylistic mark on his subsequent compositions. His 1975 visit to Kenya with the World Council of Churches introduced him to African rhythms and sonorities that he incorporated in various pieces. He also began to address the folk materials of North American Indian cultures, and those elements were evident in the orchestral work he wrote for the Philadelphia Orchestra on the occasion of the United States Bicentennial in 1976. In Native American Portraits he included Cheyenne melodies, a Seneca ceremonial song, and Pueblo dances. His preoccupation with world musics and non-Western forms permeates nearly all of his music, as do rhythmic and improvisatory jazz features. Transparency of feeling and emotion, as well as the spiritual dimensions of music, are paramount for him. “I am concerned with making the music as true in feeling as I can,” he has said. Amram’s chamber and solo music includes Discussion for flute, cello, piano, and percussion; a sonata for unaccompanied violin; Fanfare and Processional; Three Songs for Marlboro; and The Wind and the Rain. Among his choral works are Songs from Shakespeare, Psalms, and various liturgical-biblical text settings. The World of David Amram—an hour-long documentary presented on National Educational Television networks in 1969—included the premiere of his Three Songs for America. In general, his music bespeaks a contemporary yet highly personal idiom. “It is untouched by the dictates of stylish fashion,” wrote New York Herald Tribune critic William Flanagan, “or, on the other hand, the opportunism that so often plagues the work of composers associated with the commercial theater and drama.” Amram has always valued spirit and emotional message over form, device, or technique. “For this reason I find the constant battle between style and content to be meaningless,” he has explained. “What is said is paramount”—i.e., not so much how it is said. He is moved most by music he considers to be timeless and “always contemporary,” and he finds the music of Machaut and Monteverdi as “modern” as Bartók and Stravinsky. For him, truly great contemporary music belongs as much to history as to the present or the future. And he is convinced that both jazz and world musics can deepen our appreciation of the classical canon—even of such composers as Beethoven, Mozart, and Brahms. “We can listen with a bigger heart.” Amram has always felt strongly about the importance of bringing music to people at an early age. For more than twenty-five years he was the music director of young people’s and family concert programs for the Brooklyn Philharmonic. At some of those programs he demonstrated and played on unusual and exotic instruments. “It is tremendously important for professional people to work with the young,” he claims. “That is the way a true music culture is created—not through merchandising, but through love.” Amram has been described as “continuously open to experience”—whether aesthetic, ethnic, or religious. Indeed, both he and his music defy categorization. He believes that music more closely approaches the heart of genuine religious experience than any other form of communication. At the conclusion of many of his own concerts, he involves the entire audience. “We must get back to the idea of music as something in which everyone can participate. It’s a way of getting back to our spiritual roots. I want to show that music can be shared...without losing high standards in any way.” —Neil W. Levin |

This interview was recorded at his hotel in Chicago on July 4, 1986.

Portions were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1988, 1990, 1995 and

2000. The transcript was made and posted on this website early in 2014.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.