|

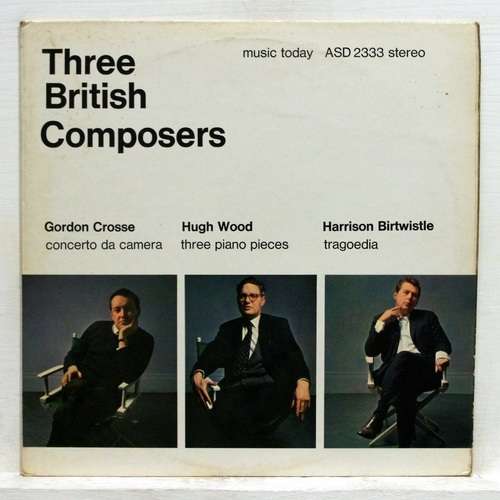

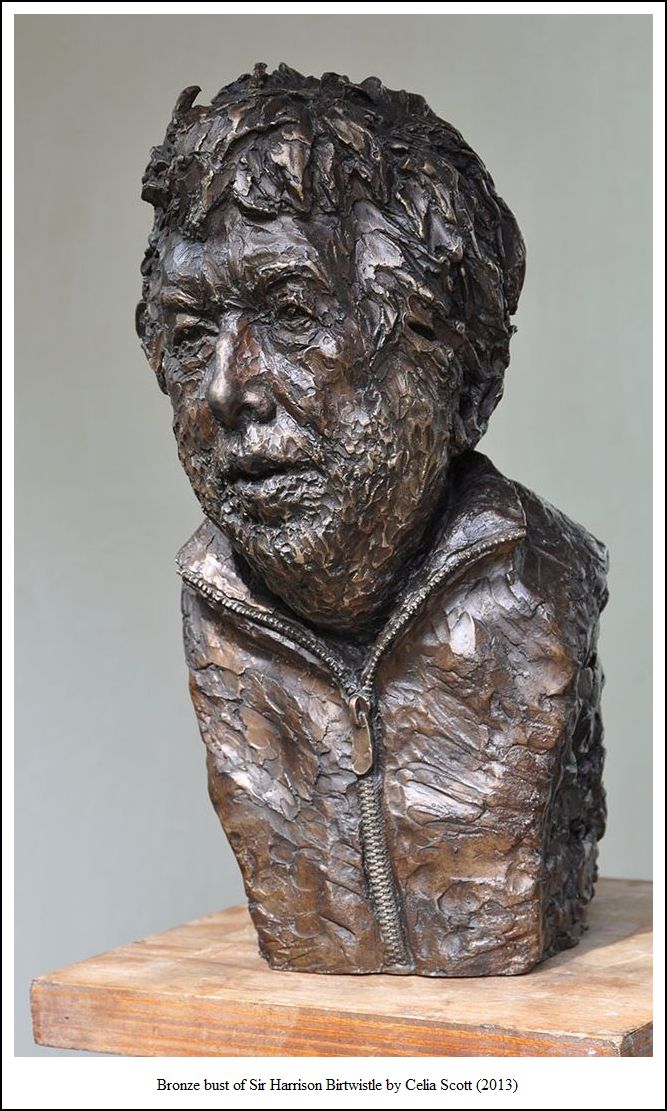

Sir Harrison Birtwistle was born in Accrington in the north of England

in 1934 and studied clarinet and composition at the Royal Manchester College

of Music, making contact with a highly talented group of contemporaries

including Peter Maxwell

Davies, Alexander Goehr, John Ogdon and Elgar Howarth. In 1965 he

sold his clarinets to devote all his efforts to composition, and travelled

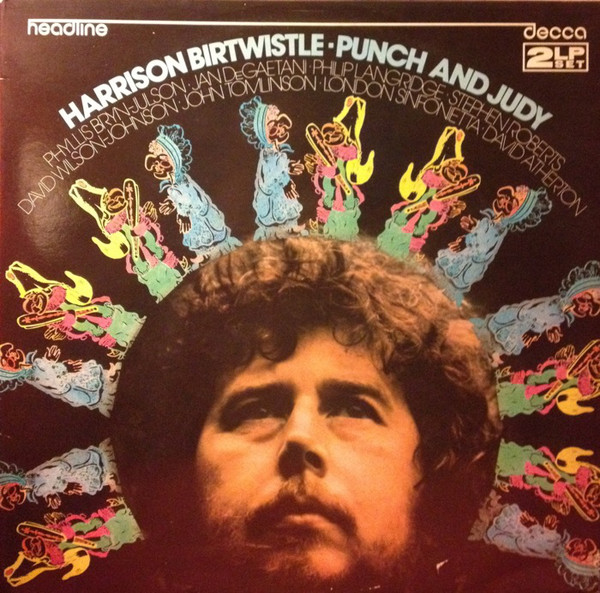

to Princeton as a Harkness Fellow where he completed the opera Punch

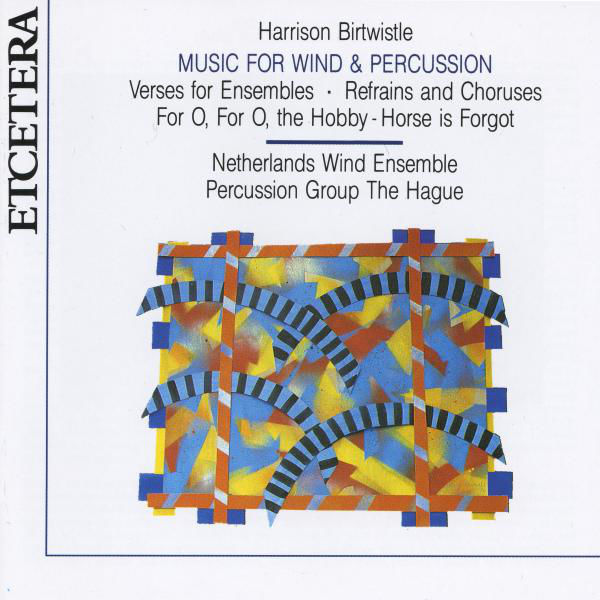

and Judy. This work, together with Verses for Ensembles and

The Triumph of Time, firmly established Birtwistle as a leading

voice in British music.

The decade from 1973 to 1984 was dominated by his monumental lyric tragedy The Mask of Orpheus, staged by English National Opera in 1986, and by the series of remarkable ensemble scores now performed by the world's leading new music groups: Secret Theatre, Silbury Air and Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum. Large-scale works in the following decade included the operas Gawain and The Second Mrs Kong, the concertos Endless Parade for trumpet and Antiphonies for piano, and the orchestral score Earth Dances. Birtwistle's orchestral works since 1995 include Exody, premiered

by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Daniel Barenboim, Panic

which received a high profile premiere at the Last Night of the 1995

BBC Proms with an estimated worldwide audience of 100 million, and The

Shadow of Night commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra

and Christoph von Dohnányi.

The Last Supper received its first performances at the Deutsche

Staatsoper in Berlin and at Glyndebourne in 2000. Pulse Shadows,

a meditation for soprano, string quartet and chamber ensemble on poetry

by Paul Celan, was released on disc by Teldec and won the 2002 Gramophone

Award for best contemporary recording. Theseus Game, co-commissioned

by RUHRtriennale, Ensemble Modern and the London Sinfonietta, was premiered

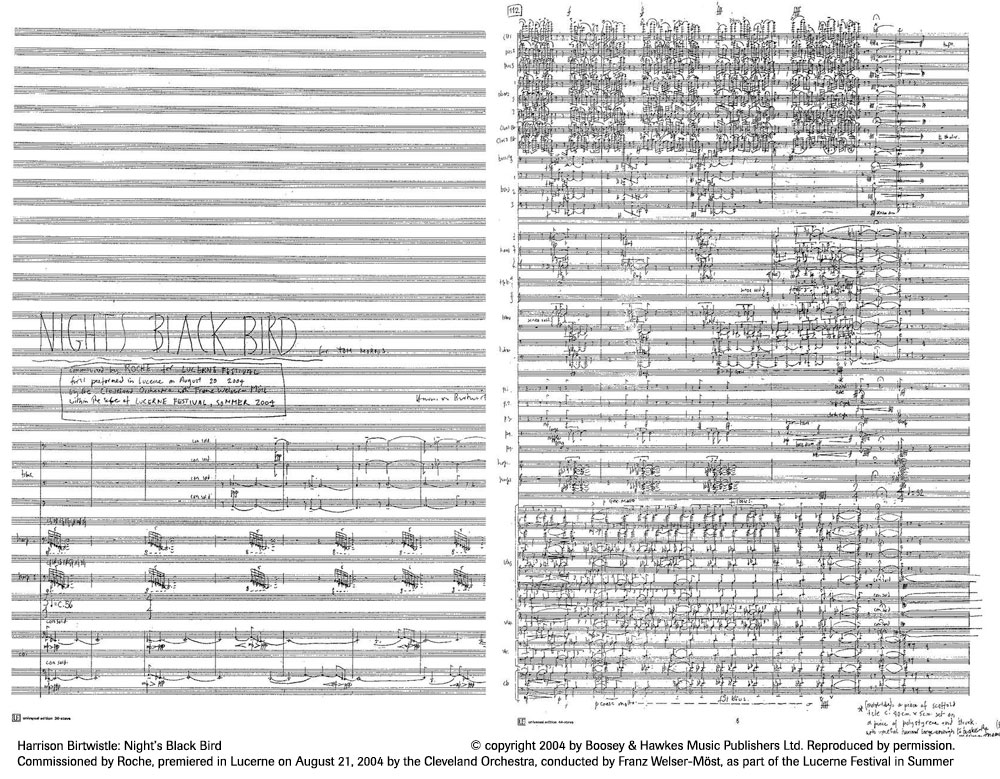

in 2003. The following year brought first performances of The Io

Passion for Aldeburgh Almeida Opera and Night's Black Bird

commissioned by Roche for the Lucerne Festival. His opera The Minotaur

received its premiere at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden in 2008 and

has been released on DVD by Opus Arte.

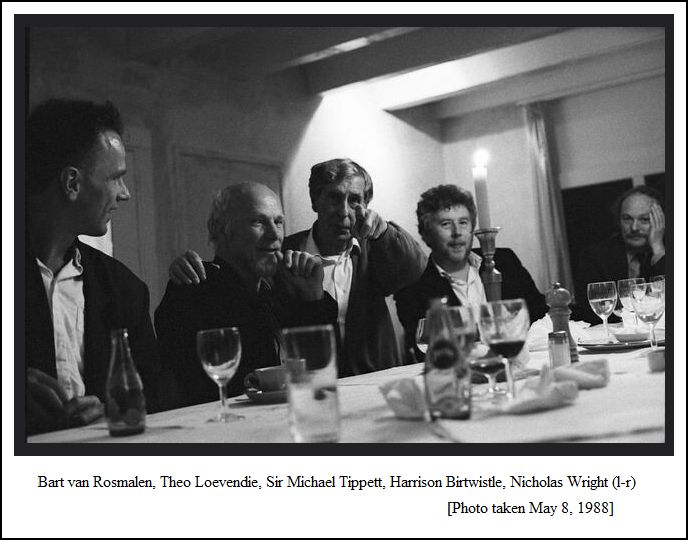

The music of Birtwistle continues to attract international conductors including Daniel Barenboim, Christoph von Dohnányi, Oliver Knussen, Sir Simon Rattle, Peter Eötvös, Franz Welser-Möst, Paul Daniel and Martyn Brabbins. He has received commissions from leading performing organisations and his music has been featured in major festivals and concert series including the BBC Proms, Salzburg Festival, Glyndebourne, Holland Festival, Lucerne Festival, Stockholm New Music, Wien Modern, Wittener Tage, the South Bank Centre in London, the Konzerthaus in Vienna, MiTo in Turin and Milan and Casa da Música in Porto. Birtwistle has received many honours, including the Grawemeyer Award in 1968 and the Siemens Prize in 1995; he was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1986, awarded a British knighthood in 1988 and made a Companion of Honour in 2001. He was Henry Purcell Professor of Music at King's College, University of London (1995-2001) and is currently a Visiting Professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Recordings of Birtwistle's music are available on the Decca, Philips, Deutsche Grammophon, Teldec, Black Box, NMC, CPO, Metronome and Soundcircus labels. Harrison Birtwistle is published by Boosey & Hawkes. December 2017. Reprinted by kind

permission of Boosey & Hawkes [Text only - photos from other sources]

|

Sir HB: I have a fairly sort of funny life

in my working arrangements. For instance, I haven’t done any

work for about eight months, but then previous to that, I’d worked every

day for three years. I’m not a person of habit or pattern.

Sir HB: I have a fairly sort of funny life

in my working arrangements. For instance, I haven’t done any

work for about eight months, but then previous to that, I’d worked every

day for three years. I’m not a person of habit or pattern. Sir HB: I don’t know. The history of English music is

strange.

Sir HB: I don’t know. The history of English music is

strange.

Sir HB: Interpretation is a funny thing,

especially for the great performers. I listened to Alfred Brendel playing

Beethoven the other day, and one thing about that was that it sounds

like Beethoven’s Beethoven, not Brendel’s Beethoven. It’s the sort

of performing that I really admire. Very often when we talk about

interpretation, you hear somebody’s version of the composer’s music,

and that is not the sort of thing that interests me. It becomes

a vehicle for them, rather than them being a vehicle for the music, and

it becomes, then, a version of what it is.

Sir HB: Interpretation is a funny thing,

especially for the great performers. I listened to Alfred Brendel playing

Beethoven the other day, and one thing about that was that it sounds

like Beethoven’s Beethoven, not Brendel’s Beethoven. It’s the sort

of performing that I really admire. Very often when we talk about

interpretation, you hear somebody’s version of the composer’s music,

and that is not the sort of thing that interests me. It becomes

a vehicle for them, rather than them being a vehicle for the music, and

it becomes, then, a version of what it is. Sir HB: [Thinks a moment, then remarks on the pause] Long

silence! [Continues his silent consideration, then verbalizes his

thoughts] For one thing, it’s unique, isn’t it? It expresses

things that you can’t express in any other way. I don’t know, maybe

it doesn’t have any purpose. Whatever purpose it has, it is in great

danger of being devalued in the way that sound is treated. It becomes

like the wallpaper to our lives. It’s on in restaurants. It’s

on wherever you turn, and has nothing to do with the quality of it, but

just the idea that there is some sort of music going on. You pick

up the telephone, there’s something. If you go through the airwaves,

it’s like garbage — it’s all up there, and

consequently there’s a result that music simply becomes wallpaper, and we

don’t listen to it. It’s something that we have on, and if you make

a complaint — for instance, in a restaurant

or something — they say that everybody

demands it. But people don’t demand it! However, as soon as

you turn it off, then they want it, but they didn’t even know it was on

in the first place. Consequently, look what happens if you write a

piece of music which is, to some extent, against that; a piece of music

like mine that they’re playing here in Chicago, which demands a concentration.

It’s to do with the drama, or having a beginning and an end.

It’s to do with many things, and people can’t accept it on that level. It

would be very easy to write the sort of music which would simply replace

that satiation in the way that we listen to classical music

— whether we really do, or perhaps we just become

familiar with it. Do we ever question whether a piece of music is

a good piece? I remember being in Cleveland where they were also

playing the Dvořák Cello Concerto. I was talking to

them about my piece, and I mentioned this point, and asked if they questioned

the fact that as to whether the Dvořák Cello Concerto is

a great piece of music. This was sort of arrogance, and I said,

“Consider the ending. I think that it’s an

absolute cop-out! Is this the right ending for the

piece, or could it have been something else?”

I happen to think it’s a cop-out, and it doesn’t work. What was

happening there was that nobody had ever considered that maybe Dvořák

was capable of doing anything wrong.

Sir HB: [Thinks a moment, then remarks on the pause] Long

silence! [Continues his silent consideration, then verbalizes his

thoughts] For one thing, it’s unique, isn’t it? It expresses

things that you can’t express in any other way. I don’t know, maybe

it doesn’t have any purpose. Whatever purpose it has, it is in great

danger of being devalued in the way that sound is treated. It becomes

like the wallpaper to our lives. It’s on in restaurants. It’s

on wherever you turn, and has nothing to do with the quality of it, but

just the idea that there is some sort of music going on. You pick

up the telephone, there’s something. If you go through the airwaves,

it’s like garbage — it’s all up there, and

consequently there’s a result that music simply becomes wallpaper, and we

don’t listen to it. It’s something that we have on, and if you make

a complaint — for instance, in a restaurant

or something — they say that everybody

demands it. But people don’t demand it! However, as soon as

you turn it off, then they want it, but they didn’t even know it was on

in the first place. Consequently, look what happens if you write a

piece of music which is, to some extent, against that; a piece of music

like mine that they’re playing here in Chicago, which demands a concentration.

It’s to do with the drama, or having a beginning and an end.

It’s to do with many things, and people can’t accept it on that level. It

would be very easy to write the sort of music which would simply replace

that satiation in the way that we listen to classical music

— whether we really do, or perhaps we just become

familiar with it. Do we ever question whether a piece of music is

a good piece? I remember being in Cleveland where they were also

playing the Dvořák Cello Concerto. I was talking to

them about my piece, and I mentioned this point, and asked if they questioned

the fact that as to whether the Dvořák Cello Concerto is

a great piece of music. This was sort of arrogance, and I said,

“Consider the ending. I think that it’s an

absolute cop-out! Is this the right ending for the

piece, or could it have been something else?”

I happen to think it’s a cop-out, and it doesn’t work. What was

happening there was that nobody had ever considered that maybe Dvořák

was capable of doing anything wrong. Sir HB: Yes, of course.

Sir HB: Yes, of course. BD: Usually composers find to make snips here and there.

BD: Usually composers find to make snips here and there. BD: Why?

BD: Why?

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 8, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.