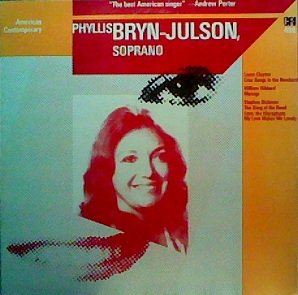

| Recognized as one of the most authoritative

interpreters of vocal music of the 20th century, Phyllis Bryn-Julson commands

a remarkable repertoire of literature spanning several centuries. Born in

North Dakota, she began studying the piano at age three. She enrolled in Concordia

College in Moorhead, Minnesota, studying piano, organ, voice and violin.

She received an Honorary Doctorate from Concordia in 1995. After attending

the Tanglewood summer music festival, she transferred to Syracuse University,

studying voice with Helen Boatwright, completing her BM and MM degrees. During

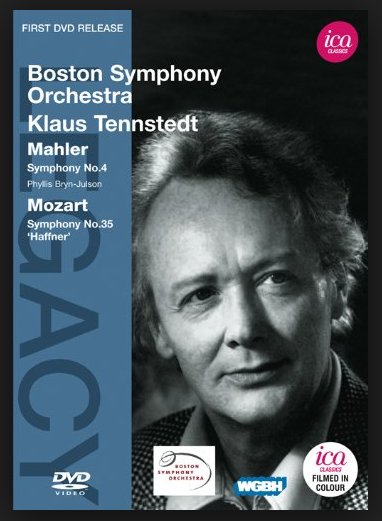

these college years, she made her debut with the Boston Symphony in Boston,

Providence, RI, and Carnegie Hall in New York. She ultimately sang with this

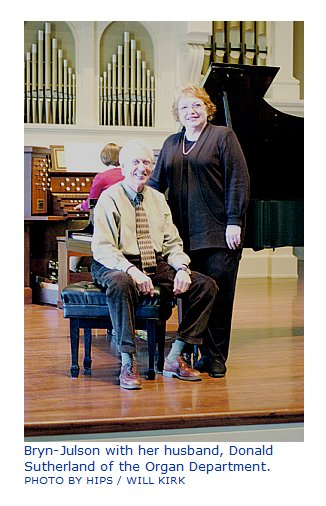

orchestra and the New York Philharmonic dozens of times. Ms. Bryn-Julson collaborated with Pierre Boulez and the Ensemble Intercontemporaine for much of her career, taking her to numerous festivals in Europe, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the former Soviet Union, and Japan. She has premiered works of many 20th century composers, some of which were written for her. Included in this list are Boulez, Messiaen, Goehr, Kurtag, Holliger, Tavener, Rochberg, Del Tredici, Rorem, Carter, Babbitt, Birtwistle, Boone, Cage, Felciano, Wuorinen, Aperghis, and Penderecki. In recent years, Ms. Bryn-Julson gave performances of Kurtag's Kafka Fragments in New York at the Guggenheim Museum with Violaine Melançon, violinist. She took part in the Radical Past series in Los Angeles, giving four performances of the great works of Milton Babbitt, John Cage, Cathy Berberian, and Luciano Berio. She toured with the Peabody Trio throughout the United States and Canada, and recorded works of Samuel Adler for the Milken Foundation in Barcelona. She also toured with the Montreal Symphony, performing the award winning opera Il Prigioniero by Dallapiccola. Performances occurred at Carnegie Hall, and in Montreal. Following this, she premiered the same work in Tokyo, Japan, where it was staged and televised. With Southwest Chamber Music Society, Ms. Bryn-Julson has performed and recorded the complete works of both Ernst Krenek and Mel Powell. Last season she premiered and recorded An American Decomeron by Richard Felciano, commissioned by the Koussevitsky Foundation, and written for her and the Southwest Chamber Music Society. With over 100 recordings and CD's to her credit, Ms. Bryn-Julson's performance of Erwartung by Schönberg (Simon Rattle conducting) won the 1995 best opera Grammaphone Award. Her recording of the opera Il Prigioniero by Dallapiccola won the Prix du Monde. She has been nominated twice for Grammy awards; one for best opera recording (Erwartung), and best vocalist (Ligeti Vocal Works). She has received the Amphoion Award, The Dickinson College Arts Award, The Paul Hume Award, and the Catherine Filene Shouse Award. She was inducted into the Scandinavian-American Hall of Fame in 2000. She was the first musician to receive the United States - United Kingdom Bicentennial Exchange Arts Fellowship. She received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Syracuse University, the Peabody Conservatory Faculty Award for excellence in teaching, and the Peabody Student Council Award for outstanding contribution to the Peabody Community. Ms. Bryn-Julson has appeared with every major European and North American Symphony Orchestras under many of the leading conductors such as Esa-Pekka Salonen, Simon Rattle, Pierre Boulez, Leonard Slatkin, Leonard Bernstein, Claudio Abbado, Seiji Ozawa, Zubin Mehta, Gunther Schuller, and Erich Leinsdorf. Ms. Bryn-Julson's students continue to win prizes and awards, and have made careers in some of the leading opera houses and orchestral venues. They have had contracts in opera houses in Zurich, Duesseldorf, Vienna, Paris, Lyons, London, and Sydney, and in America, the Metropolitan Opera, Houston, Minnesota, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Washington, D.C -- From the website of the Peabody Institute

of Johns Hopkins University, where she is Chair of Voice

[Note: Names which are links (both in this biography, and below in the conversation) refer to interviews with Bruce Duffie found elsewhere on this website.] |

PB-J: Not from that summer, no, not really.

I’ve certainly done a little bit of everybody, I suppose. I certainly

know the repertoire. Careers can go in many directions for whatever

reasons — some reasons I don’t even know. Managers manage my life, and

so sometimes I’m doing things that I really don’t know why or how it happened.

Usually I find out, but sometimes, however, I’m in a situation where I really

don’t know how it happened, or why, for instance, I have a whole season of

Mahler and no modern music whatsoever.

PB-J: Not from that summer, no, not really.

I’ve certainly done a little bit of everybody, I suppose. I certainly

know the repertoire. Careers can go in many directions for whatever

reasons — some reasons I don’t even know. Managers manage my life, and

so sometimes I’m doing things that I really don’t know why or how it happened.

Usually I find out, but sometimes, however, I’m in a situation where I really

don’t know how it happened, or why, for instance, I have a whole season of

Mahler and no modern music whatsoever.  PB-J: Each voice is unique because there are different

stress points. In general, a dramatic soprano is always going to be

Wagnerian or Verdian. In general, the lyric soprano is always going

to be able to do certain lyric roles, but in the end there still is one thing.

There could be one or two different notes or variations in the human voice

that would be different than anybody else’s, and those are things that one

must find out. I always say I’m in the practice of teaching like the

practice of medicine. You bring in a new student and you listen and

you look and you study and you try to observe, and it’s going to be a little

different from the other lyric soprano I had in the same room.

PB-J: Each voice is unique because there are different

stress points. In general, a dramatic soprano is always going to be

Wagnerian or Verdian. In general, the lyric soprano is always going

to be able to do certain lyric roles, but in the end there still is one thing.

There could be one or two different notes or variations in the human voice

that would be different than anybody else’s, and those are things that one

must find out. I always say I’m in the practice of teaching like the

practice of medicine. You bring in a new student and you listen and

you look and you study and you try to observe, and it’s going to be a little

different from the other lyric soprano I had in the same room. PB-J: Yes, I guess you are if one has listened

to it a great deal. But if one begins to tear apart the score to even

put together the complexities of the chordal progressions and so forth, this

is really outrageous, unbelievably difficult! But it is the cleanliness

of the singing of the Mozart. You can’t really sing Mozart with an enormous

wobble or a very dramatic voice, and get by with it for a very long time.

PB-J: Yes, I guess you are if one has listened

to it a great deal. But if one begins to tear apart the score to even

put together the complexities of the chordal progressions and so forth, this

is really outrageous, unbelievably difficult! But it is the cleanliness

of the singing of the Mozart. You can’t really sing Mozart with an enormous

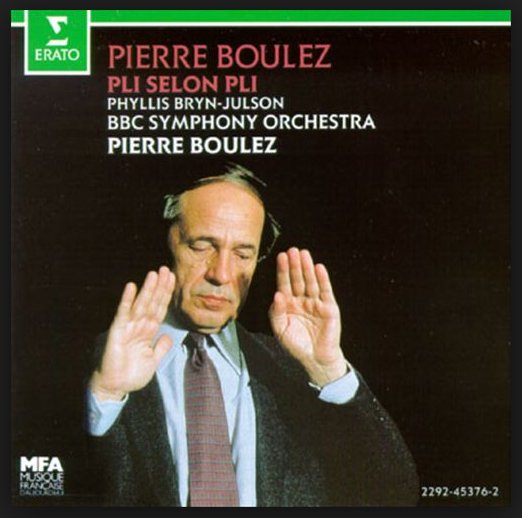

wobble or a very dramatic voice, and get by with it for a very long time. PB-J: Well, that’s probably not, but in the recordings

I do I’ve been really fortunate. It’s usually with people who like to

go through it and then cover the spots that were bad. I think piecing

together a piece is just tiring and you lose it; you don’t have a piece at

all. I’ve been so lucky with Boulez. It’s just a dream to record

with that man. It’s very clear. Of course I’m a little nervous,

and usually the first time through sounds nervous, but he knows that.

I know that. The orchestra knows that. So we’ll do it one time

through. You have to get the cobwebs out, and then the second time through

sparkles happen and so do mistakes. So we just cover those mistakes

and we’re done. It’s really wonderful. I think the hardest one

I did with him was the Pli selon pli

because all of us wanted to make this the most perfect recording of this

piece. We wanted everything lined up, everything in tune and yet very

beautiful. It took us forever! It was three long days of recording.

It was hard.

PB-J: Well, that’s probably not, but in the recordings

I do I’ve been really fortunate. It’s usually with people who like to

go through it and then cover the spots that were bad. I think piecing

together a piece is just tiring and you lose it; you don’t have a piece at

all. I’ve been so lucky with Boulez. It’s just a dream to record

with that man. It’s very clear. Of course I’m a little nervous,

and usually the first time through sounds nervous, but he knows that.

I know that. The orchestra knows that. So we’ll do it one time

through. You have to get the cobwebs out, and then the second time through

sparkles happen and so do mistakes. So we just cover those mistakes

and we’re done. It’s really wonderful. I think the hardest one

I did with him was the Pli selon pli

because all of us wanted to make this the most perfect recording of this

piece. We wanted everything lined up, everything in tune and yet very

beautiful. It took us forever! It was three long days of recording.

It was hard. PB-J: Most of the time — if

everything is going well, if my voice is working right, if I didn’t have to

blow up at anybody today, if I didn’t have to scream at anyone or have an

argument... It’s really peculiar — it’s not the

kind of life that is at all normal when you think about it. You go

off to a hotel. You can’t talk to too many people because then you’d

lose your voice for the concert. Somebody might say something wrong

that just irritates you the wrong way. Any little thing like that

can take away the special adrenaline or the moment, the sparkle that goes

into the performance. So that’s the hard part. Whether that’s

fun, I don’t know. Fun comes when you’re in the middle of the piece

and things are going well and everybody’s really doing their job and you

feel it in the room. You feel it with the audience; you feel it with

the conductor. That’s fun.

PB-J: Most of the time — if

everything is going well, if my voice is working right, if I didn’t have to

blow up at anybody today, if I didn’t have to scream at anyone or have an

argument... It’s really peculiar — it’s not the

kind of life that is at all normal when you think about it. You go

off to a hotel. You can’t talk to too many people because then you’d

lose your voice for the concert. Somebody might say something wrong

that just irritates you the wrong way. Any little thing like that

can take away the special adrenaline or the moment, the sparkle that goes

into the performance. So that’s the hard part. Whether that’s

fun, I don’t know. Fun comes when you’re in the middle of the piece

and things are going well and everybody’s really doing their job and you

feel it in the room. You feel it with the audience; you feel it with

the conductor. That’s fun. PB-J: No, certainly not. I have my favorites

like anybody else. When you’re looking at a style or a period or a type

of music, especially in the 20th century, one can go at it many ways.

One can take it just by itself and leave it there. You’ve just heard

this piece of Boulez and you just take it for what it is, or you can be a

little more broad-minded and put it in the context of the French evolution

of writing. Or you can even go so far as to compare it to someone like

Messiaen — one of the great French teachers

— or Boulanger to see where are the influences here and where

does Boulez fit in. He studied with Messiaen, but there is very little

Messiaen in the writing of Boulez, yet there is an overall French-ness about

everything. Boulez would hate that, however! But one can look

at it then with this programming, which was absolutely superb. Barenboim

should be congratulated for putting the Ravel at the end because that really

tied it all together. It’s the 20th century going backwards. Then

you begin to see. It’s like with paintings; it’s the same in the art

world. You can look at a progression in a country and you can almost

see, certainly, the social times. You can see what was happening politically

in many instances. I can’t say that about the Boulez work, but I just

think that if you can approach it in a way of looking at the music, it can

be done in many, many ways, not to just be single-minded and say this it’s

René Char and it’s Mallarmé or whoever, and it’s at this moment

and I must accept this now. Put it in the context with the program or

with the history. Then it becomes fun to really do a little digging.

Who were these poets? What were they all about? What were they

doing? They were sitting in cafés. What was happening at

the time? It must have been fascinating in Paris at that period.

It must have been wonderful.

PB-J: No, certainly not. I have my favorites

like anybody else. When you’re looking at a style or a period or a type

of music, especially in the 20th century, one can go at it many ways.

One can take it just by itself and leave it there. You’ve just heard

this piece of Boulez and you just take it for what it is, or you can be a

little more broad-minded and put it in the context of the French evolution

of writing. Or you can even go so far as to compare it to someone like

Messiaen — one of the great French teachers

— or Boulanger to see where are the influences here and where

does Boulez fit in. He studied with Messiaen, but there is very little

Messiaen in the writing of Boulez, yet there is an overall French-ness about

everything. Boulez would hate that, however! But one can look

at it then with this programming, which was absolutely superb. Barenboim

should be congratulated for putting the Ravel at the end because that really

tied it all together. It’s the 20th century going backwards. Then

you begin to see. It’s like with paintings; it’s the same in the art

world. You can look at a progression in a country and you can almost

see, certainly, the social times. You can see what was happening politically

in many instances. I can’t say that about the Boulez work, but I just

think that if you can approach it in a way of looking at the music, it can

be done in many, many ways, not to just be single-minded and say this it’s

René Char and it’s Mallarmé or whoever, and it’s at this moment

and I must accept this now. Put it in the context with the program or

with the history. Then it becomes fun to really do a little digging.

Who were these poets? What were they all about? What were they

doing? They were sitting in cafés. What was happening at

the time? It must have been fascinating in Paris at that period.

It must have been wonderful.This interview was recorded at her hotel following the Chicago Symphony

concert of May 9, 1991. Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB

in 1995 and 2000. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. The transcription

was made and posted on this website in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.