A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

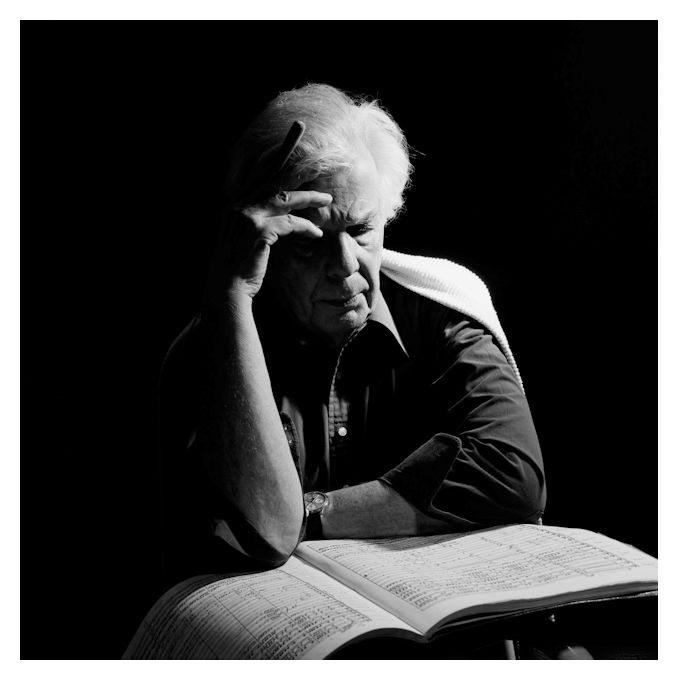

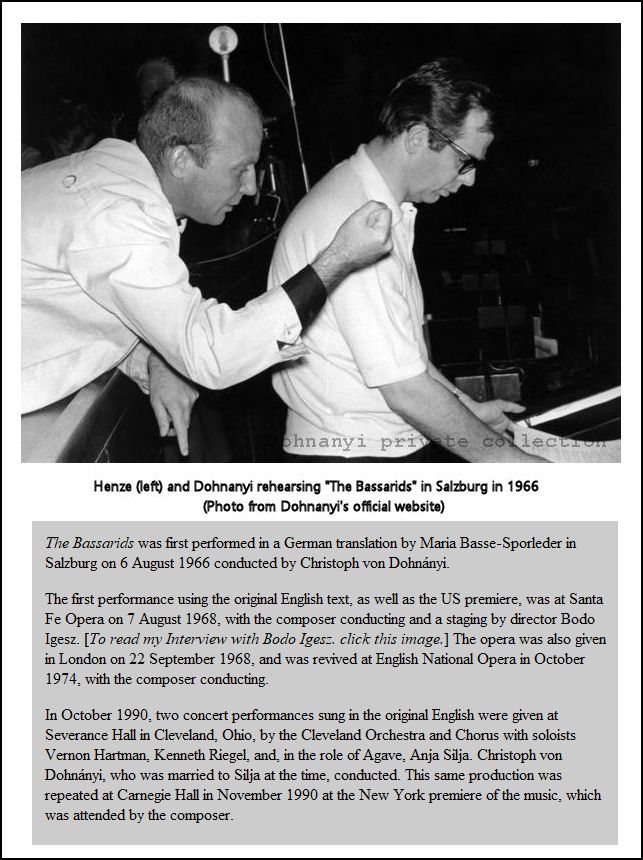

Christoph von Dohnányi was born in Berlin on September 8, 1929 to jurist Hans von Dohnányi and Christine Bonhoeffer. His uncle on his mother's side, and also his godfather, was Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran pastor and theologian/ethicist. His grandfather was the pianist and composer Ernő Dohnányi, also known as Ernst von Dohnányi. His father, uncle and other family members participated in the German Resistance movement against Nazism, and were arrested and detained in several Nazi concentration camps before being executed in 1945, when Christoph was 15 years old. Dohnányi's older brother is Klaus von Dohnányi, a German politician and former mayor of Hamburg. After World War II, Dohnányi studied law in Munich, but in 1948 he transferred to the Hochschule für Musik und Theater München to study composition, piano and conducting. At the opera in Munich, he was a stage extra, coached singers, and was a house pianist. He received the Richard Strauss Prize from the city of Munich, and then went to Florida State University to study with his grandfather.

As director of the Frankfurt Opera and with his team including Gerard Mortier (Director of Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels, Salzburg Festival, Opéra de Paris), Peter Mario Katona (Director of Casting at ROH Covent Garden) and Klaus Schultz, Dramaturg in Munich (Bayerische Staatsoper) and Berlin (Philharmonic Orchestra), then General Manager of the Stadttheater Aachen, Nationaltheater Mannheim, and Gärtnerplatztheater in Munich, the balance in programming of traditional opera performance and innovative Musiktheater, promoting the idea of Regietheater, established Frankfurt opera as a leading house at that time. He continued this concept in Hamburg. Dohnányi's fame stems largely from his relationship with the Cleveland Orchestra that spanned two decades. He made his conducting debut with the orchestra in December 1981, and soon after was appointed music director designate from 1982 to 1984 and consequently served as music director from the 1984-85 season until August 2002. At the time of Dohnányi's appointment, he was relatively unknown compared to previous musical directors Lorin Maazel and George Szell, with whom the Cleveland Orchestra "achieved what was probably the highest executant standard of any orchestra in the world" according to music critic Theodore Libbey. Dohnányi and Szell had a similar micro-managerial conducting style, and in Dohnányi's tenure with the Cleveland Orchestra, the orchestra pursued an active touring and recording schedule, being often described as the finest in the United States, "more or less on a par with the august philharmonics of Vienna and Berlin", according to The New York Times. In spite of such praise, Dohnányi's name was often mentioned only after Szell's in concert reviews. Dohnányi remarked in the late 1980s, "We give a great concert...and George Szell gets a great review." During the time when the city of Cleveland was in a dire financial condition, the joke went, "What's the difference between Cleveland and the Titanic? Cleveland has the better orchestra!" Dohnányi made many recordings with them, and was named the first ever "Music Director Laureate of the Cleveland Orchestra" upon his retirement in 2002. During his tenure, Severance Hall in Cleveland underwent a substantial extension and renovation, bringing back the Norton Memorial Organ that had been banned from stage during George Szell's tenure. As Music Director he initiated the foundation of The Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra. The Cleveland Orchestra Youth Chorus was founded as well, both organisations being active in Northeast Ohio for the education in and enhancement of symphonic music. From 1998 to 2000 Dohnányi was also Artistic Advisor of the Orchestre de Paris. In 1994, Dohnányi became the principal guest conductor of London's Philharmonia Orchestra, and in 1997 their Principal Conductor. In April 2007, Dohnányi was one of eight conductors of British orchestras to endorse the 10-year classical music outreach manifesto, "Building on Excellence: Orchestras for the 21st Century", to increase the presence of classical music in the UK, including giving free entry to all British schoolchildren to a classical music concert. In 2008, he stepped down from the Philharmonia principal conductorship and now holds the title with the orchestra of "Honorary Conductor for Life". After retiring as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra, Dohnányi has been a guest conductor with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Chicago Symphony and Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as the Cleveland Orchestra. He has performed frequently at the Tanglewood Music Festival with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. A regular collaboration has developed with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra since the 1990s. In 2004, Dohnányi returned to Hamburg, Germany where he maintained a residence for many years, to become chief conductor of the NDR Symphony Orchestra. He concluded his NDR tenure after the 2009-2010 season. He has been a frequent guest conductor in concert with the Vienna Philharmonic and at the Vienna State Opera. With the Philharmonia Orchestra, Dohnányi performed throughout Europe at such venues as the Musikverein in Vienna, the Salzburg Festival, Amsterdam's Concertgebouw, the Lucerne Festival, and Paris's Théâtre des Champs Elyseés. For several seasons, Dohnányi and the Philharmonia Orchestra were in residence at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, performing new productions of Richard Strauss's operas Arabella, Die Frau ohne Schatten and Die schweigsame Frau, Arnold Schoenberg's Moses und Aron, Igor Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex and Engelbert Humperdinck's Hänsel und Gretel. At the Opernhaus Zürich, Dohnányi led new productions of Moses and Aron, Oedipus Rex (with Béla Bartók's Bluebeard's Castle), Strauss's Die Schweigsame Frau, Ariadne auf Naxos, Salome, Elektra, and Die Frau ohne Schatten, Mozart's Idomeneo, Giuseppe Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera, and Richard Wagner's The Flying Dutchman. His conducting schedule permitting, Dohnányi also works with

student orchestras of institutions like the New England Conservatory in

Boston, Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, the Juilliard School in New York,

the Cleveland Institute of Music, and during the summer at the Tanglewood

Music Center. As a mentor to younger artists, Alan Gilbert, current music

director of the New York Philharmonic, was assistant conductor to Dohnányi

from 1995 to 1997 at the Cleveland Orchestra. Jens Georg Bachmann, music

director of the Crested Butte Music Festival in Colorado, had been in the

same position at the NDR Symphony Orchestra from 2007 to 2009. Among his many honors Christoph von Dohnányi has received honorary doctorates of Music from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, Oberlin College of Music, Cleveland Institute of Music, Kent State University and Case Western Reserve University, London's Royal Academy of Music, and an honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters from the Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion, and the Anti-Defamation League’s Torch of Freedom Award. He is the recipient of the Goethe plaque of the city of Frankfurt, the prize of Wissenschaft and Forschung of the city of Hamburg and the Bartok medal in Hungary. He is a member of the Order of Arts and Letters of France, and received the Verdienstkreuz of the Republic of Austria and the Bundesverdienstkreuz of the Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Dohnányi has been married three times. His first wife was

the German actress Renate Zillessen, and they had two children, Katja

and Justus. His second wife was the German soprano Anja Silja, with whom he

had three children: Julia, Benedikt and Olga. Dohnányi married

his third wife, violinist Barbara Koller, in 2004. -- Names which are links refer to my Interviews

elsewhere on my website. BD

|

CvD: Just the music in both of them. [Laughs]

Conducting, as a skill is far over-rated. Moving the hand

is not so difficult. Really hearing well and judging and balance,

and knowing the music is our profession.

CvD: Just the music in both of them. [Laughs]

Conducting, as a skill is far over-rated. Moving the hand

is not so difficult. Really hearing well and judging and balance,

and knowing the music is our profession.  BD: Is it right that some of the pieces come in and

go out, and come in and go out again over generations?

BD: Is it right that some of the pieces come in and

go out, and come in and go out again over generations?  BD: You’ve had a long and distinguished

career. Do you find that there are some surprises, such as pieces

you didn’t think excited you and all of a sudden they do?

BD: You’ve had a long and distinguished

career. Do you find that there are some surprises, such as pieces

you didn’t think excited you and all of a sudden they do? |

Don Juan in Hell is the long third act of the play Man and Superman (1903), which shows Don Juan himself having a conversation with several characters in Hell. This act is often cut. Charles A. Berst observes of Act III: Paradoxically, the act is both extraneous and central to the drama which surrounds it. It can be dispensed with, and usually is, on grounds that it is just too long to include in an already full-length play. More significantly, it is in some aspects a digression, operates in a different mode from the rest of the material, delays the immediate well-made story line, and much of its subject matter is already implicit in the rest of the play. The play performs well without it.Don Juan in Hell consists of a philosophical debate between Don Juan (played by the same actor who plays Jack Tanner), and the Devil, with Doña Ana (Ann) and the Statue of Don Gonzalo, Ana's father (Roebuck Ramsden) looking on. This third act is often performed separately as a play in its own right, most famously during the 1950s in a concert version, featuring Charles Boyer as Don Juan, Charles Laughton as the Devil, Cedric Hardwicke as the Commander and Agnes Moorehead as Doña Ana. |

Christoph von Dohnányi at Lyric

Opera of Chicago

1969 - Flying Dutchman with Silja, Stewart, Talvela, Cox; Ebermann, Wolf Siegfried

Wagner

1970 - Rosenkavalier with Ludwig, Minton, Berry, Garaventa, Zilio, Andreolli, Brooks; Neugebauer, Schneider-Siemssen 1971 - Salome with Silja, Ulfung, Cervena, Nienstedt, Little, Zilio, Andreolli, Drake; Lehmann/Darling, Pizzi 1972 - Masked Ball with Arroyo, Tagliavini, Milnes, Kozut, Baldani, Ferrin, Voketaitis; Gobbi, Darling Così Fan Tutte with Price, Howells, Davies, Krause, Kozut, Evans; Ponnelle (dir & des) 2004-05 - Fidelio with Mattila, Begley, Struckmann, Pape, Bayrakdarian, Davislim, Held; Lapinski, Israel, Schuler |

BD: Do you like jetting all over

the world?

BD: Do you like jetting all over

the world?  BD: So you want more control over it then?

BD: So you want more control over it then?

© 2005 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 9, 2005. Portions were broadcast on WNUR a few weeks later, and again in 2014; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2007 and 2009. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.