PRINCIPAL HARP SARAH BULLEN TO RETIRE AFTER

24 YEARS OF SERVICE TO THE CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

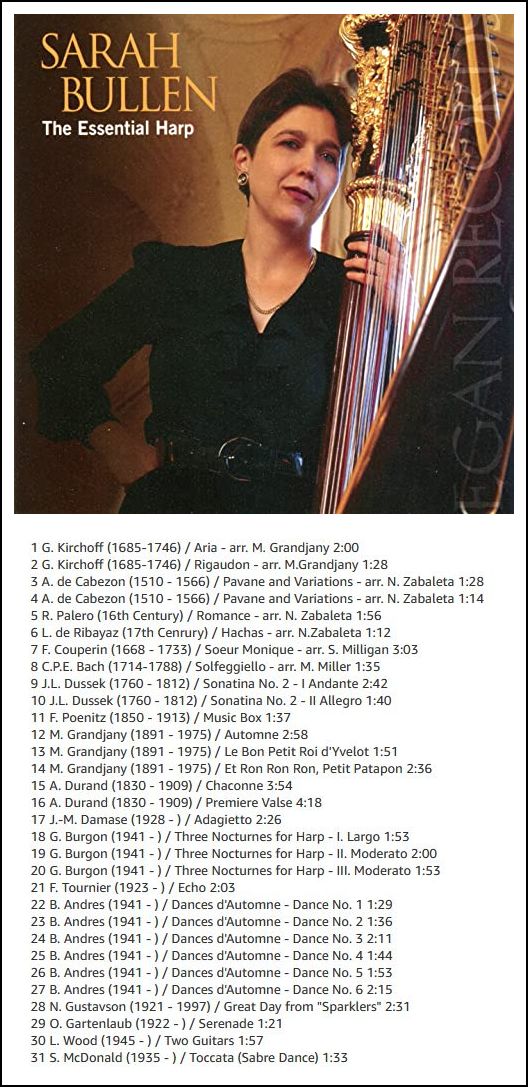

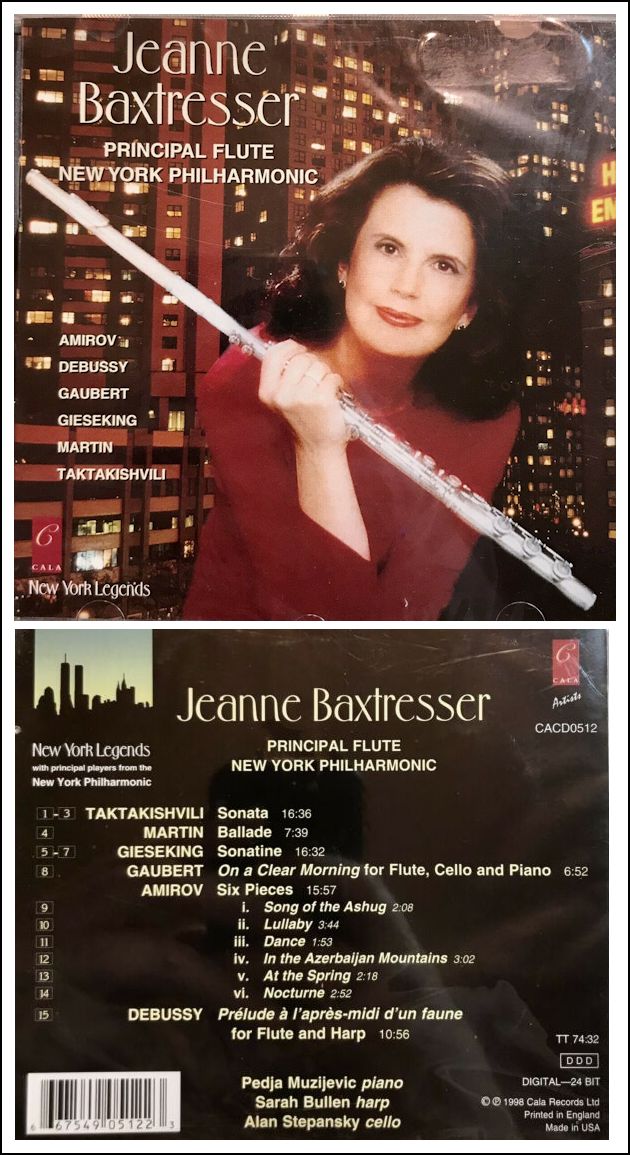

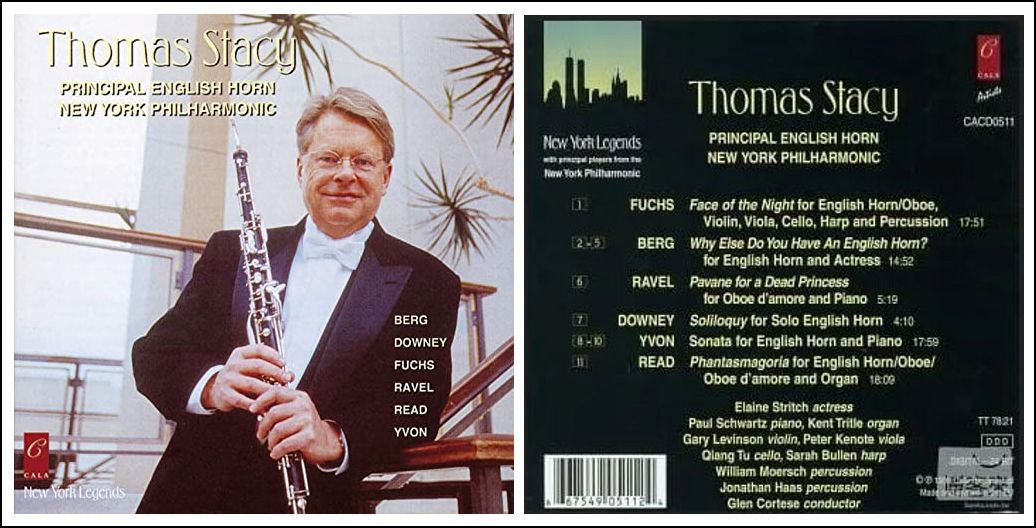

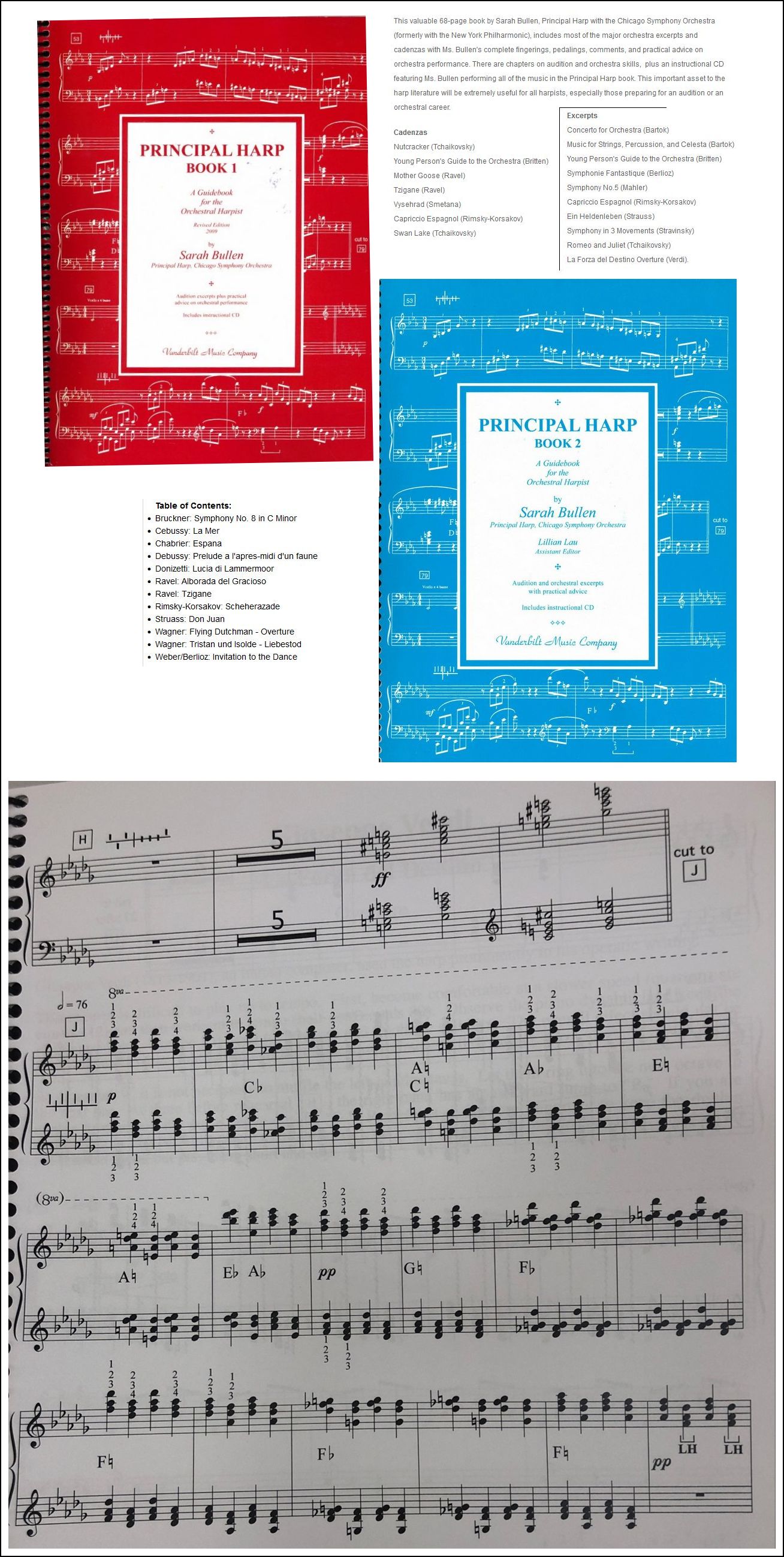

(...) In 1997, Bullen was appointed to the position of principal harp by then-Music Director Daniel Barenboim. Prior to the CSO, Bullen was principal harp of the New York Philharmonic from 1987 to 1997, having been appointed to the position by then-Music Director Zubin Mehta. She began her orchestral career 40 years ago in 1981 as principal harp of the Utah Symphony. During her CSO tenure, Bullen has performed on more than 20 international tours with the Orchestra and appeared as a soloist with the CSO multiple times including appearances with Daniel Barenboim in Ginastera’s Harp Concerto, and with Pierre Boulez in Debussy’s Sacred and Profane Dances, a work she also performed with Riccardo Muti in her most recent solo appearance in 2018. Throughout her career, Bullen has won critical acclaim in more than 50 concerto appearances, including those with the New York Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta and Erich Leinsdorf and orchestras around the world. Bullen has also served as a soloist, chamber musician, lecturer and judge at numerous American Harp Society conferences and at the World Harp Congress and the USA International Harp Competition. For her achievements in the field, she was also recognized as one of the foremost harpists of the 20th century in Harp Column magazine. As a leading educator, Bullen has taught master classes throughout the world. During her tenure in New York, she served as chairperson of the harp department of the Manhattan School of Music. In Chicago, she was a professor of harp at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts for several years through 2016 and continues to maintain a private studio. Several of Bullen’s students have gone on to enjoy major professional careers. She is the author of the best-selling book Principal Harp: A Guidebook for the Orchestral Harpist, in two volumes. Bullen is also the co-author of Anthology of Harp Duets, Volume One, published in 2016 by Lyon & Healy. Her solo and chamber music recordings include The Essential Harp and Lyon & Healy Hall’s Inaugural Concert with the latter featuring performances by Bullen along with fellow CSO musicians Louise Dixon (flute) and Max Raimi (viola). Originally from Long Island, New York, Bullen was a student of Marcel Grandjany, Mildred Dilling and Susann McDonald. As a Naumburg Award recipient, she graduated from the Juilliard School with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music. == From a CSO press release (with minor corrections)

announcing Bullen’s retirement from the orchestra effective in September,

2021

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewheree on my website. BD |

© 2003 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded backstage at Orchestra Hall in Chicago on October 5, 2003. Portions were broadcast on WNUR the following week, and again in 2014. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.