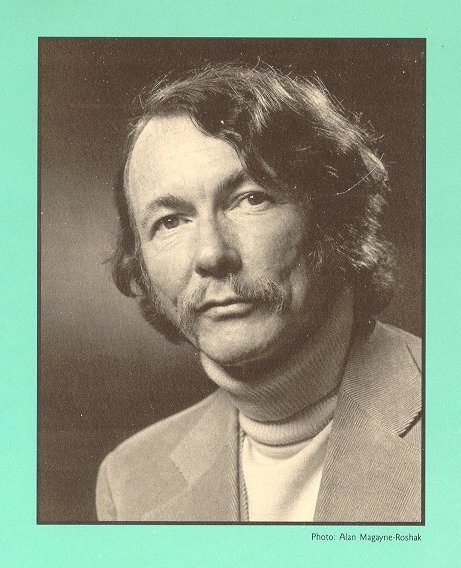

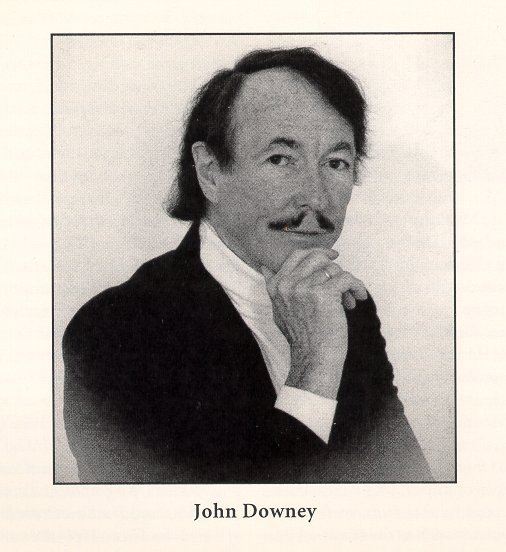

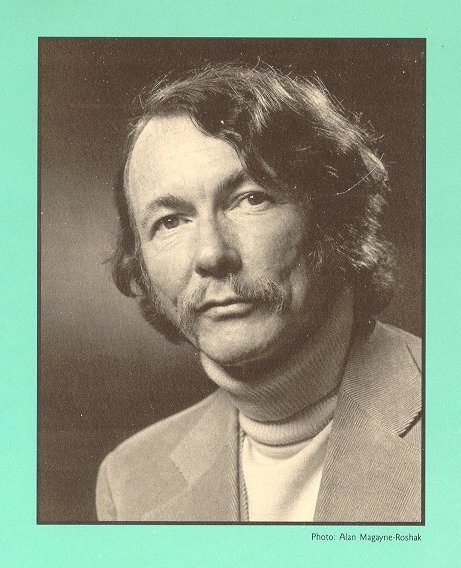

Composer John Downey

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

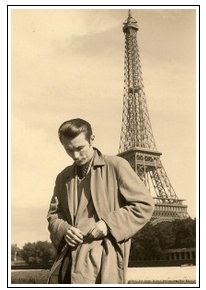

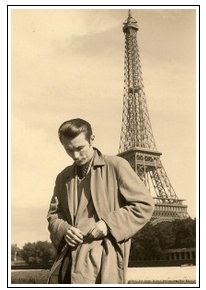

A native of Chicago, John Downey

[October 5, 1927 - December 18, 2004] earned a Bachelor of Music degree

from DePaul University and a Master of Music from the Chicago Musical College

of Roosevelt University, while working at night as a jazz pianist. Downey

was later awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study with his mentors Honegger,

Milhaud and Boulanger in Paris, where he earned a Prix de Composition from

the Paris Conservatoire National de Musique, and a Ph.D.(Docteur des Lettres)

from the University of Paris Sorbonne. Given the title of “Chevalier

de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres” for his scholarly achievements, Downey

was knighted by the French government in 1980.

|

There are several of my guests with whom I have remained close over the

years, but John Downey is the only who has written a piece about the neighborhood

in which I live! It’s called

Eastlake Terrace, and my home is

just a few blocks from this very short street. I actually use it often

when driving home from Evanston or other places to the north. Indeed,

one time, when I was doing an interview with a pianist who played works of

Downey, I made sure that when we were in the car we drove along this very

thoroughfare just so he would have traversed it. He was duly impressed...

In anticipation of his 60th birthday, I arranged to interview John Downey.

I drove up to his home in suburban Milwaukee, and we spent a nice bit of

time exploring his world. Several times he waxed philosophically about

nature or circumstance, and I have included most of these verbal fantasies

in this transcription. Names which are links refer to my Interviews

elsewhere on this website.

While I was setting up to record our conversation, we chatted a bit about

some of his recordings, and that is where we pick up the thread

. . . . . . . . .

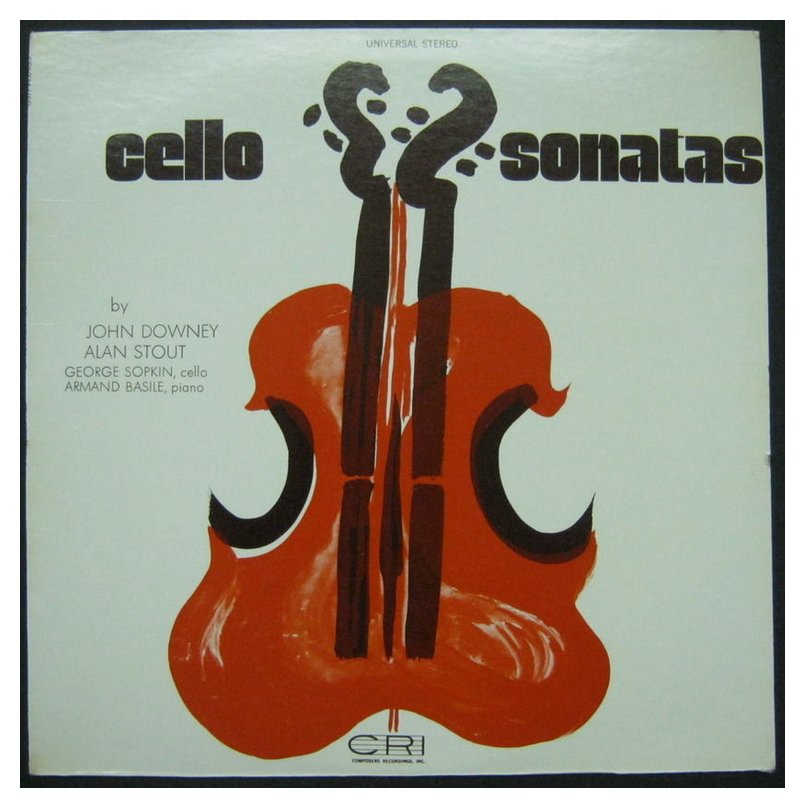

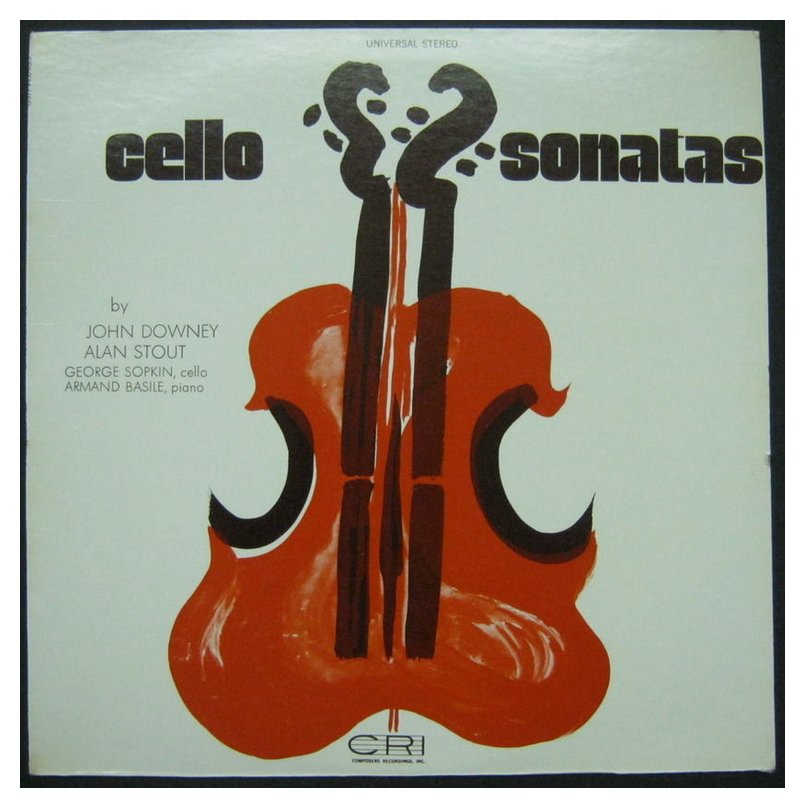

John Downey:

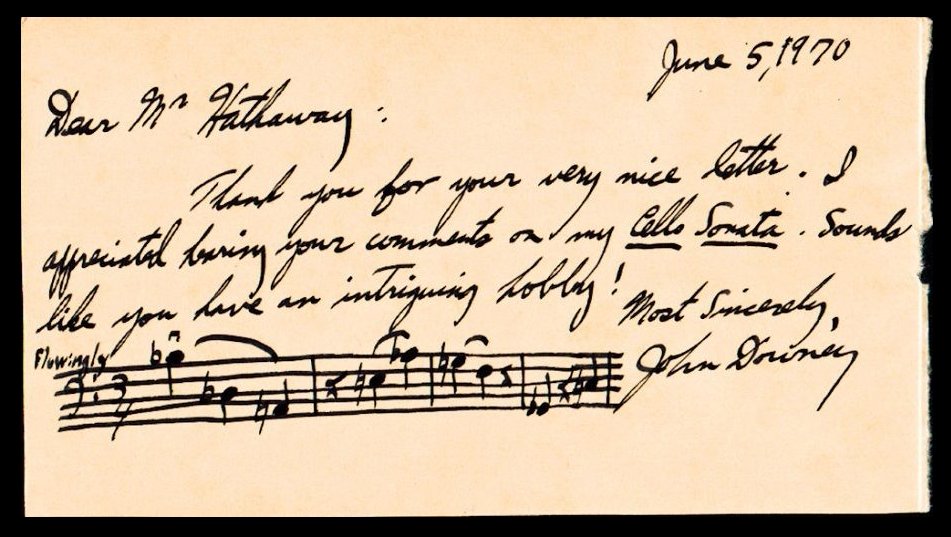

That CRI record is my Cello Sonata,

with that of another Chicago composer, Alan Stout. He teaches

at Northwestern, and we were both to receive commissions to write a work

for cellist George Sopkin of the Fine Arts String Quartet. It was interesting

to me because before that I didn’t know about Alan — except

that he was at Northwestern — and he didn’t know

anything about me. So we both wrote these works. Mine dates

from 1966 and I think his probably dates from the same time because it was

being premiered in the spring of the following of the following year.

I started mine in the fall of 1965 and finished a few months later, and

then Sopkin played it in April. We both used some similar techniques

on the cello. and seemed manic at times, and yet the pieces are totally

different in spirit. But there are certain mean points where you could

say these two guys really were of the same place and same time.

Bruce Duffie:

Is there a certain quality in the air? Are there certain nuances that

all composers, or many composers, who were working in the same time would

pick out?

JD: I suppose

so. The most notorious example of that is between Debussy and Ravel,

I suppose. Ravel was younger and obviously he didn’t copy from Debussy,

but he certainly was influenced by Debussy. For the French in that

country at a certain time, color was obviously such a primordial factor in

creation. When you think of visual painters, then the sound painters

like Debussy and Ravel both came from an environment particularly stimulating

in terms of the color. If anyone were to describe Impressionism, it’s

that sense of color. When you hear the orchestrations of Debussy and

Ravel, it’s just color. Debussy has a lot of things going for him;

they both do, but that’s one factor that really puts them apart from most

other composers of their time.

BD: The point

I’m getting at, though, was that it seems music is moving in a certainly

inevitable direction, and if one composer weren’t there, some other composer

would do the same kind of thing.

JD: Yes, I

see what you mean.

BD: Schoenberg

said that if he hadn’t been Schoenberg, somebody else would have been.

JD: I think that’s probably true. There’s

a certain advancement in terms of chromaticism, and the next logical step

in his period had to be something beyond what Wagner had already accomplished.

It wasn’t just Wagner, but he’s probably the principle innovator of his time

for the use of non-stop melodic lines and a tremendous sense of orchestration

that he had. As you say, if he hadn’t done it somebody else would have.

Today, after a lot of twelve-tone meandering all the way up to pre-determined

music and the intellectual approach, I noticed as a teacher in composition

that young people just really didn’t want that. You kind of shove

that down their throats as part of the technique everybody has to know,

but in the 1950s and ’60s, that was still pretty much

in a vogue in this country. But as you get into the 1970s and particularly

the ’80s, that is no longer a firm procedure that

most every young composer adopts. All young composers are exposed

to it, but you have a much greater diversity, especially since ‘minimalism’

came in such vogue. People like Philip Glass and

Steve Reich, and particularly

John Adams — who combines a lot of other things in

it — give you more of hook up with traditionalists.

Composers are on a different road now. Probably the most influential

composer in this country in a populist theme was George Crumb. His

pieces are exceedingly dramatic. They’re very mystic in so far as he

has a lot of other than strictly musical forces working on his pieces.

But they’re not just strict, turgid, at the mercy of one particular technique.

JD: I think that’s probably true. There’s

a certain advancement in terms of chromaticism, and the next logical step

in his period had to be something beyond what Wagner had already accomplished.

It wasn’t just Wagner, but he’s probably the principle innovator of his time

for the use of non-stop melodic lines and a tremendous sense of orchestration

that he had. As you say, if he hadn’t done it somebody else would have.

Today, after a lot of twelve-tone meandering all the way up to pre-determined

music and the intellectual approach, I noticed as a teacher in composition

that young people just really didn’t want that. You kind of shove

that down their throats as part of the technique everybody has to know,

but in the 1950s and ’60s, that was still pretty much

in a vogue in this country. But as you get into the 1970s and particularly

the ’80s, that is no longer a firm procedure that

most every young composer adopts. All young composers are exposed

to it, but you have a much greater diversity, especially since ‘minimalism’

came in such vogue. People like Philip Glass and

Steve Reich, and particularly

John Adams — who combines a lot of other things in

it — give you more of hook up with traditionalists.

Composers are on a different road now. Probably the most influential

composer in this country in a populist theme was George Crumb. His

pieces are exceedingly dramatic. They’re very mystic in so far as he

has a lot of other than strictly musical forces working on his pieces.

But they’re not just strict, turgid, at the mercy of one particular technique.

BD: Seeing

music as an inevitable force, you don’t feel constricted in what you’re

writing? You don’t feel you’re being held back or pushed in a wrong

direction in your music?

JD: No.

I did notice that I’ve become quite overtly romantic in the last five years

I would say. It just occurred. When I was younger I wrote a lot.

I did my twelve-tone pieces and I did predetermined things that I was experimenting...

like in the Cello Sonata I had

a rhythmic row. It had seventeen factors or twenty-one factors, or

something, but I don’t even remember all that. I was doing all of

this mental approach to how my music was going to be explainable later, and

it was actually nice and stimulating. But after a while I found there

are basically two approaches that you could probably divide most composers

into. There are those who are trying to evolve into a technique when

they’re quite young, regardless of whether it is original to them or not.

They got onto a technique, and they try to really maintain it and perhaps

go into depths. But they write in a somewhat predictable manner; not

that each piece is the same, but the technical approach is fairly constant.

And then there are other composers, and they usually say, “I

try to make each new piece a new discovery.”

That’s kind of nice. I like that they’re traveling in uncharted waters,

but neither extreme perhaps is true. Somewhere in the middle you have

to ascertain what each composer is about, and the only way you can truly do

that is to compose and have some pretty good output. You begin to seize

that through a number of pieces. Certain gestures begin to be curved,

and if they’re strong enough you begin to link those with a given composer,

and they become part of his musical personality. Pretty soon you say,

“Oh, that’s a John Downey piece, or a George Crumb

piece, or whatever...”

BD: You can

see your fingerprints all over the piece?

JD: Yes, I

think so if the composer’s strong enough. And if that doesn’t happen,

his music is probably either too subtle and too minute to differentiate

for people to perceive at the time, or it’s a composer who has a rather

pale personality and his music probably won’t live. There’s been so

much created, particularly in the last twenty-five years, that we know about.

Maybe a lot of music was composed all the time, but now with producing methods

like Xeroxing and tape recorders, all the dissemination of material is so

immense that is scary! [Both laugh] But by and large, the really

good pieces by strong composers do nonetheless emerge, and they maintain

their personality. A lot of the novelties are striking on first hearing,

but don’t maintain their real originality, their real personality.

For example, take a theme like with electronics and reverberation.

The first few examples of that in the late 1950s and ’60s

were striking, but then radio stations and commercials began to play it all

the time and it became such a gimmicky thing. I won’t try to make any

analogy with the certain composers who are somewhat in that category, trying

to latch onto whatever is the latest, whatever’s evolved, what the newest

is, and then trying to pass it off as their own thing.

BD: Well, what

should be then the ultimate purpose of music?

JD: To communicate

something to one’s fellow creatures. What one communicates is the sensitivity

of an artist to events around him or her, and how you react to the society

in which you live. If you’re sensitive, then you get the first makings

of an artist, whether you’re a painter or a poet or a musician or a composer.

Then the question of technique comes in. If you decide to be a composer,

do you have a good ear? Do you have a good imagination to begin with?

That’s important. Do you have an imagination that is translatable

into tone and color?

BD:

Do you decide to become a composer, or is this thrust upon you?

BD:

Do you decide to become a composer, or is this thrust upon you?

JD: I can only

speak personally. When you’re young, you feel you want to say something.

You have real strong feelings — whether it’s about

love or about death or about birth or about friendship — you

want to somehow express it. This is why I say you dance, or you

jump for joy, and if you’re a composer you probably started having piano

lessons or violin lessons or something when you were a kid. Whether

your parents pushed you into it or you asked for it, it’s how it affected

you. Then the next step is to try and express what you feel through

tones, and before you know it, if you have something really strong to say

you probably manage to put that together in some sort of coherent whole, and

you get a piece. Maybe it’s not a very good piece but you begin, and

as you get more feelings from various sorts, that’s reflected in an artist’s

work.

BD: So the

music that comes out of any composer is going to be the culmination of all

the input up to that point?

JD: I think

so. The difference between one composer and another would be the way

in which he or she filters that information. Let me turn that around.

When you’re reading history books about composers like Haydn and Mozart

— well, Mozart’s so great it’s almost obscene to bring him into

our discussion because he’s just so God-like — but

let’s say Beethoven. You read about Beethoven being sometimes really

what you might call a plain individual. He was not really mercenary,

but he wanted to see that he got his just due for what he did. He was

good, damn good, and he knew it, and he wanted these patrons of the arts to

really recognize it — not just by giving him a pat on

the back, but from a pecuniary standpoint. “I

have to live too, sir!” So when you read about

some of his groveling in the economic difficulties, how could this man write

such glorious music? Also when you read about his impediment, his hearing

and all that. But still the art transcends the surface of what seems

to be the environment in which the person lived, such as the health of Schubert.

What happened to such a tremendously gifted composer had to be so tragic,

yet at the same time he overcame that and came out with this glorious music.

He had to feel it, and who knows, maybe in Austria at that time there was

a certain emphasis on nature. Still, a sunset is a sunset. It’s

a thing of beauty; or a running brook through a stream can happen anywhere

in the world. That happened thousands and thousands of years ago and

it still happens today, and a sensitive person reacts to how it’s expressed,

and changes for each different epoch — what’s in the

air, what techniques are current, and now, for instance, what the instruments

can do in an orchestra is pretty astounding. Yet there are composers

who forgo that because of all the difficulties and politics of getting a

piece played by an orchestra. They write for synthesizers and for computers.

All these things have somewhat enlarged the potential vocabulary of a composer,

but they don’t change fundamentally how one reacts. If you are a person

of great depth of feeling, and let’s say your wife dies tragically or your

parents are killed, you’re going to be moved by that, and very deeply.

But some people, I don’t know if you call them superficial or not, but they

react less deeply to events, and they seem to get over it quickly.

Others seem to be much more affected by events.

BD: Are you

saying that saying everyone should be affected to the same degree?

JD: No, but

I’m saying that different artists have different depth of reaction to events,

and because of that, their music — with the means by

which they’re going to express what they feel — is

going to be colored somewhat by that personality. Take a composer

like Shostakovich. During World War II he’s a man who obviously was

impacted by certain tragic events. They were going around him.

Igor Stravinsky was a little bit different because he left his homeland

during the Bolshevik Revolution and lived abroad. Prokofiev left Russia

and lived in France, but he returned to Russia and certainly reacted to

the War years, also. But his reaction is quite different to that of

Shostakovich. There are two composers using somewhat similar technical

music, but yet I don’t think anyone could miss their two styles. They’re

quite different.

BD: So let’s

take the composer John Downey now! As you approach your sixtieth birthday,

you’ve lived through a number of major economic and political changes in

the world.

JD: That’s

right.

BD: Have these

all impacted upon your music, and if so, do they continue to?

JD: Yes, and

no. Let’s take the ‘no’ part first. It’s probably difficult,

if not impossible, to equate events that happened around you on a one-to-one

basis as to what you really do in the music. Let me give examples!

On one recording there’s a piece called Adagio Lirico for two pianos. I

wrote that when I was very young, and it’s a very romantic piece.

But I still like it!

BD: Why do

you sound so surprised when you say that you still like it?

JD: I’ll come

back to that. As you get older you supposedly get wiser, but that’s

not necessarily inevitable. When I look back at some of my earlier

pieces, some of them really were bad. They were young and immature,

and I just hid those and ripped those up, because I’ve been composing for

a very long time. When I was about seventeen, my brother was killed

in World War II, and it was a tragic event as far as our family was concerned

because he was a medical scientist. He wasn’t yet an MD, but he was

studying to be one. So he was assigned to a hospital shift, and there

was a big invasion in the Philippine Islands, the invasion of Leyte which

was a huge battle. My brother was three years older than myself, and

he wasn’t a kind of daring guy. He did have a defect and in one of

his eyes and was virtually blind, but he wanted to be in the army.

He was assigned to medical work, so we all thought he was pretty safe.

But he wanted to tend to people’s wounds during that Invasion. Unfortunately,

in spite of the fact that he had a cross on his arm and everything, he got

shot in the back of the neck by a sniper on a tree, because there were some

of the Japanese who didn’t clear out when the Americans came in. So

he was one of those unfortunate people who got killed, and that was shocking

in a very profound sense. I didn’t really know what to do about that.

I was just very hurt by that because I remember we were planning to go to

school here together when he came out of the army. We we’re both musicians,

but Dad always wanted one of us to be an engineer. If he’d lived I

might have been an engineer, but as it was, he didn’t, and I ended up pursuing

my first real love, and that is music. In any case, I was a sole surviving

son, so four or five years later I didn’t get drafted into for the Korean

War. I became a Fulbright student and was sent to Paris. It was

only when I got to Paris that I wrote a piece that I had first called Adagio for the Dead, which was really

for my brother. In a way I tried to express what was, to me, certain

feelings about death, and in particular about this relationship of my brother

and myself and the world. So I wrote the piece. I remember when

I came back a number of years later to the States I studied with Darius Milhaud.

He asked me to Colorado where he was each summer, and when I was out there

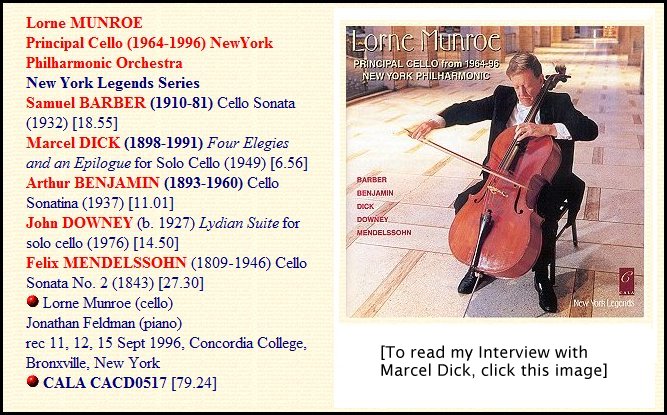

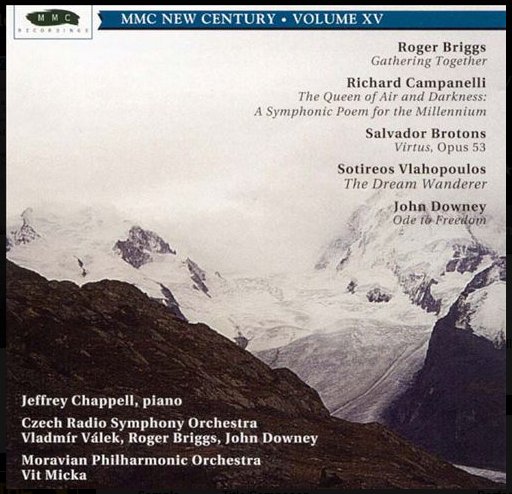

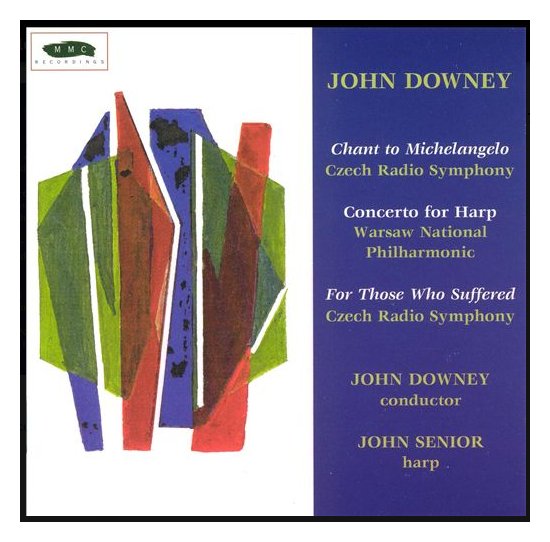

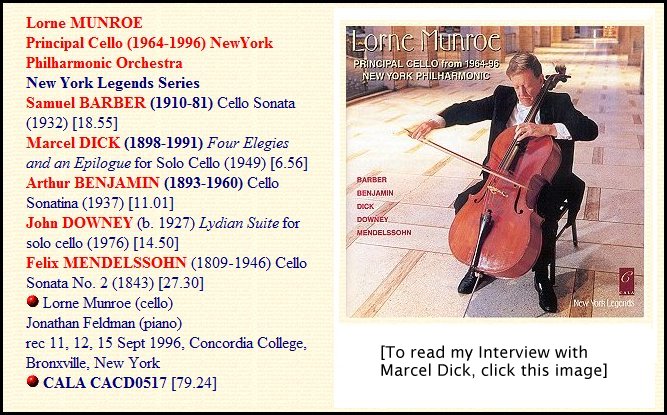

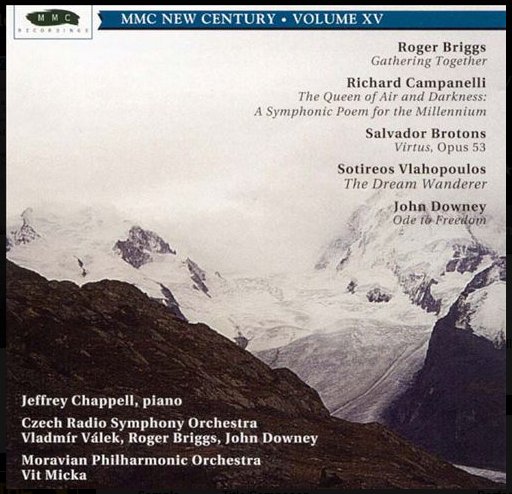

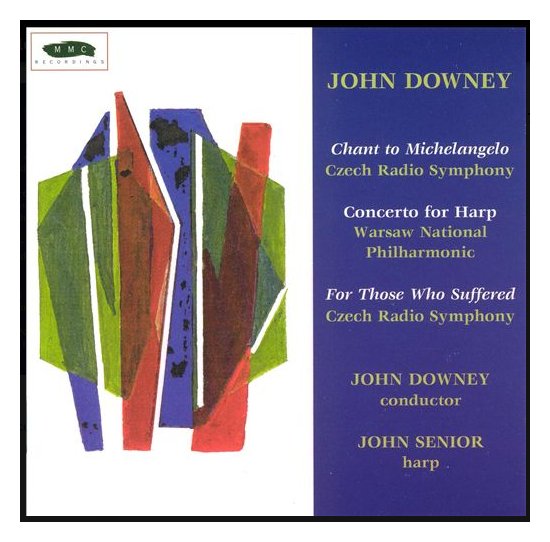

I won at prize for an orchestral piece called Chant to Michelangelo. I wrote that

at Aspen, and there’s an example of a piece that I kind of like today, but

it’s sort of immature in the sense that it has got very strong aspects of

influence in terms of the music of Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók,

and maybe Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud.

BD: And yet it’s not something you want to go

back to and tinker with to bring up to date?

BD: And yet it’s not something you want to go

back to and tinker with to bring up to date?

JD: That’s

right, yes. This is an example of a piece I like personally in certain

respects. I stayed a number of years in France. My wife got

some scholarships and we went to Italy. I had been going around Paris

as a ‘hot shot’, a young American composer, and I suppose like all youngsters

I began to say things like, “Igor Stravinsky?

I don’t listen to his music.” I’d always be

scared of the question because I knew his personality was so strong and

his stamp so irrevocable and immense. I just decided it was best to

stay away from that man. I didn’t listen to his music because, golly,

he’s so great, you know, and the moment you make any gesture remotely similar

to his, it sounds like the master. I became very interested in going

to museums and seeing first hand a lot of works, particularly Michelangelo.

I was really knocked out by his sculpture. I thought he couldn’t paint

because all I had seen was a kind of a half-finished Madonna where there

was a child. I really hadn’t seen much and I just thought he’s obviously

best at sculpturing; he works best in three dimensions — I

was on that tack. But then we got to Rome, and God, I went into that

Sistine Chapel and I saw these images of Moses, the Prophets, and everything

up on that ceiling. I just stared in disbelief. It was so enormous.

My wife and I used to discuss pretty much all of what I was doing, and I

said, “I’m going try and put that in music!”

Just the physical energy of those images was vibrant with life. So

I did a piece called Chant to Michelangelo,

and it won the Aspen Prize that summer. Vitya Vronsky and Victor Babin

heard this piece and were impressed by it, and they asked me if I had by

chance anything for two pianos. I told them that I had Adagio for the Dead, and so they listened

to the piece; they tried it out and they said they liked that piece.

Victor was at that time head of the Cleveland Institute of Music I believe,

and he contacted me and he said, “Vitya and I are going

to play my piece next year on tour, but would you consider changing the

title? We have to give programs all over the country, and

it just sounds a little bit gloomy. I’m Russian, and my friend, Rachmaninov,

has his Isle of the Dead,

and people don’t play that. They play his concertos! We want

to play your piece, and since you’re not known, you’re a young composer,

and we want to introduce you.” So I thought about

what he had said and I came up with the title Adagio Lirico, which they liked.

Unfortunately for me and that particular series of events, Vitya Vronsky

broke her little finger coming off a train, so that they had to cancel the

following year’s tour. Then the third year they only played what they

had known already. They didn’t want to do anything new that that third

year, and then the fourth year he died. He had a heart attack.

Later there were a number of people who played the piece. Joseph and

Tony Paratore took it up, and they later recorded it on that one album.

So there is a specific example, as well as my Chant to Michelangelo, of surroundings

that stimulate you. It’s a fact that I was influenced by the death

of my brother in that particular piece, but there are pieces in which there

would be no illusion to that in the title, but which may very well have been

affected by a tragic event. Sometimes paradoxically for a lot of composers,

you may be surrounded by what could categorically be classed as tragic

events, but you come out with something that is happy and gay. In

a way it’s a matter of circumventing events in which you’re smothered, and

overcoming that. It’s through your music that you manifest a new assertion

towards life. When there is death, I can certainly understand that

people celebrate by having wild parties after the funeral. I

remember reading about those in literature, also. Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is an example.

BD: When the

audience comes to hear some of your music, do you expect them to know the

circumstances surrounding the creation of the piece?

JD: No, no,

in fact it’s better that they don’t. Music has the singular beauty

of being able to enhance. If you need to get something specific across

— that this has got to be this or that — you

really need to put a program to your music. Maybe for some people initially

this is helpful, but for a sensitive listener, they will sense the feelings

that the composer is emitting, and they will register. When I am moved

by something, I get vibrations up and down the spine. Sometimes when

I’m sitting upstairs at my desk and I write something, I don’t hear any

sounds other than those which are within me, but I start vibrating.

Then I know this has got to be good; I know this is going to communicate

for some other people. I can’t really necessarily describe exactly

what I’m hearing; it’s a feeling. It’s like on a hot day there’s suddenly

a cool breeze that blows through the air, and that’s a great feeling.

How do you describe that feeling? It just occurs. Maybe it’s a

chord progression or just a modulation like in the recapitulation Beethoven

put in his Third Symphony.

That always moves me very much.

BD: Is this

perhaps what differentiates a great piece of music from a lesser piece of

music — its ability to communicate with so many others?

JD: Yes, I

think so; on different levels with different profundities if you wish.

Beethoven is one person whose depths for me are incalculable. I’m

very moved by Mozart too, but he’s so divine in a way. I’m always

mystified by that to a certain degree.

* *

* * *

BD: Let me

ask about the depth of the music by John Downey.

JD: Well, I

think that would be a little bit pompous of me to think that my music is

great. I don’t know that. I write it as if each piece is a great

piece, and I get very moved. Otherwise I obviously wouldn’t write it.

Each new piece I think is a great piece.

BD: Do you

write it to be great, or do you just see where it goes?

JD: No, but

when I’m writing I vibrate. I will give you an example. I’m writing

a work right now for Gary

Karr, the double bass virtuoso. It’s going to be premièred

in Australia, of all places, on September 1st in Sydney, at the Opera House.

I know I have a good piece. Now it’s true that when he tries it out

he may say, “Gosh, my double bass is covered here,”

or, “This is an awkward passage to do,”

or any number of things of this nature. But I’m speaking about the

music. I feel that I have some really good things. How does a

composer know that? Something inside you tells you that it’s vibrating

in the right way, and the moods are good moods to me. It may be that

it won’t come off that way, necessarily, to an audience, but at the time,

like right now, this is my feeling, and I’m working tremendously hard to

put it all in order. Then the parts have to be cleaned and ready to

go. Each portion is a little bit in that order. A concerto like

this, which is in four movements, is a pretty big piece.

BD: What do

you expect of the audience that goes to hear this piece, or any new piece

of yours?

JD: The only

thing I can expect is that certain people — or a good

percentage of them — come to my concerts because they’re

sensitive to music, and they will hear a certain motive in my music that

corresponds to what they feel. In a platonic sense it’s

almost like talking about the idea of what good sound or good composition

might be. That’s never really categorically defined because it changes

from one period to another. The styles change, but still, the sense

of proportions are pretty constant. That’s where I’m hopefully fairly

strong. I have a pretty good sense of architecture — how

a piece moves from one event to another. Do I stay long in an area?

Maybe, and that could be boring. Or do I have enough surprises in the

piece to make it continuously interesting? All this must be considered.

The reason why Karr commissioned me to do this piece is that he heard the

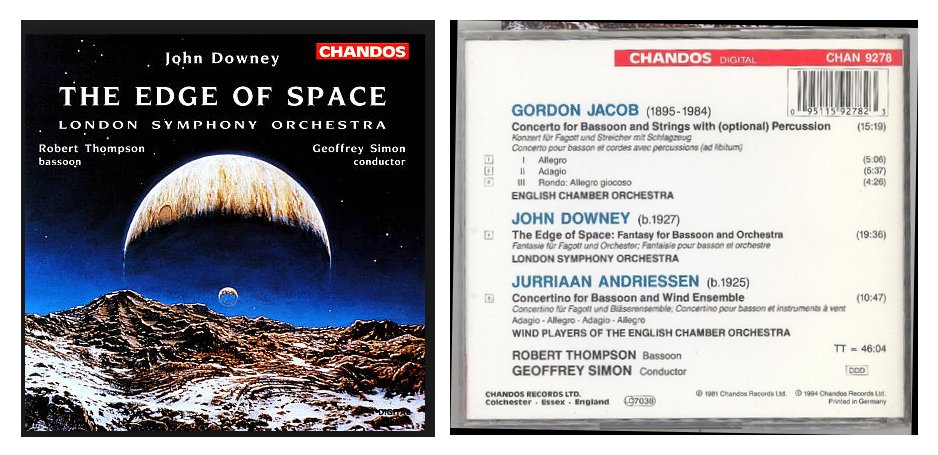

recording of The Edge of Space.

He called me from Connecticut, where he lives. The man said he was

Gary Karr and asked if I knew who he was. I said, “The double

bass virtuoso!” He said, “Yes!

Are you the John Downey that wrote this piece?”

When I said that I was, he said, “I’d be interested

just to ask you a couple of questions. When you wrote the piece, you

used a very large orchestra, and on the recording I can hear a bassoon very,

very well. When it was done in a large situation, did you have to

amplify the bassoon?” I said it wasn’t amplified

and he said that was great! I explained to him that for the recording

they had microphones all over the place in London. I had written it

on a grant from the Milwaukee Symphony, and I remember when I first showed

the score to conductor Kenneth Schermerhorn, he took a look at it and asked

if they would have to use amplification. He said, “You’ve

got such a huge orchestra, and all those crystal glasses, and bird sounds

on vibraphones. There’s such a wall of sound you’d never hear the poor

bassoon!” I said, “I hope

you’re wrong! But if you’re right why don’t you bring your microphones

to pick up the bassoon at the first rehearsal. But let’s try it without

them the first time we run through it. Let us see what happens because

I did try to imagine the sounds. But I’m not God!

There are 95 people sitting there in the orchestra, and who knows, maybe I

did make a gross error. We’re committed to do the piece, and if I did

goof we’ll have to amplify. But give it a chance!”

So he did, and lo and behold, it did work! There was no talk at all

about the amplification!

BD: You were

right!

JD: It turned

out it was right. Whether you call it intuition or luck or gift or what

not, I don’t know! It’s hard to really specifically justify why it

came out this way. But at least the track record indicated in general

that my orchestrated things sound right!

BD: So then

you’re never really surprised by what you hear, as opposed to what you thought

you were going to hear?

JD: So far

I haven’t been. Now I’m going to have a real test with the double

bass, because the double bass is yet more subtle than is the bassoon.

In the interim I’ve written two other pieces to learn more about it.

One is for solo double bass called Silhouette,

that a friend of mine, Roger Ruggeri, plays. It’s dedicated to him.

Then I had another piece called Recombinance

for double bass and piano. It has had only one performance so far,

but it was a different kind of writing. I just tried to learn more

about the instrument and what it can do. Now the big test is that

I have all the woodwinds in threes — two flutes &

piccolo, two oboes & English horn, two clarinets & bass clarinet,

two bassoons & contrabassoon, then two trumpets, four horns, two trombones,

bass trombone, tuba, and three percussion players plus timpanist, harpist

and celeste, and the big string orchestra.

BD: All fighting

against the one bass player!

JD: Yes.

I hope to God this will work! What I’m banking on instinctively is

that I’m trying to lift the sound out of the orchestra, and I’ve got a last

movement that is pretty gigantic in sound. There’s a lot going on.

I think I did it, but whether that will really happen or not remains to be

seen. But the other side of the coin is a composer who has shown some

real attractive qualities in his output, and one who gets engaged to write

for an orchestra. So the chances are the person making that gamble

feels he will succeed because you get thousands and thousands of dollars

going into one of these affairs. All the musicians sit there even if

the piece really doesn’t work. Maybe you play it and it bombs, and that’s

it. Pity the poor composer. What a loss when you put in so much

time and the effort to get one of these gigantic things done.

BD: Is it wrong,

though, on the part of the audience — and even the

musicians — to expect that every new piece is going

to work, or even work well?

JD: I think it’s wrong. I agree with you

totally. I’ll give you another example.

As a student, a youngster in Paris, I was amazed that I got admitted to

the French section of the Conservatoire. That meant that each year

your exams were to follow. You didn’t get graded like here, where

you get an A or a B, or a C, or a D for every class. It doesn’t work

that way in France. You either got a prize or you didn’t. I

was working on one composition for a given year, and at the end of the year

that piece had to be presented before a jury who would decide whether that

piece looked like it had some potential or not. If it did, then the

next step would be to have it played by the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra

— which is a damn good one, so you got good performances.

Maybe you’d be passed academically by the Board, but there were some real

lemons. But you learned, and you were given usually a limit of just

a few years to get the prize. You could still compete and gain experiences

each year from these performances. You might even get a ‘second prix

de composition’ which would give you another four or five years.

JD: I think it’s wrong. I agree with you

totally. I’ll give you another example.

As a student, a youngster in Paris, I was amazed that I got admitted to

the French section of the Conservatoire. That meant that each year

your exams were to follow. You didn’t get graded like here, where

you get an A or a B, or a C, or a D for every class. It doesn’t work

that way in France. You either got a prize or you didn’t. I

was working on one composition for a given year, and at the end of the year

that piece had to be presented before a jury who would decide whether that

piece looked like it had some potential or not. If it did, then the

next step would be to have it played by the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra

— which is a damn good one, so you got good performances.

Maybe you’d be passed academically by the Board, but there were some real

lemons. But you learned, and you were given usually a limit of just

a few years to get the prize. You could still compete and gain experiences

each year from these performances. You might even get a ‘second prix

de composition’ which would give you another four or five years.

BD: When you

write a piece like that, are you writing for the judges?

JD: You just

write because that’s what you want to say, or you like the sound.

I presented my first orchestral piece when I was studying the first year

with Nadia Boulanger. It was a Fulbright to study with Arthur Honegger,

but Honegger was already very ill, so he saw some of his students only a

few times a year. The Fulbright Commission people said I was there to

study on a more regular basis, so they arranged for me to enroll in the

Accompaniment Class with Nadia Boulanger. I’d done all that, had accompanied

singers, and I thought I knew it all. But then I went to that class.

They said to just go and give it a try, and after all, Nadia Boulanger is

a very well renowned figure. So I went, and it was score reading!

BD: You learned

more than just how to put the accompaniment behind someone?

JD: That’s

right, it was a really great experience. She soon found out that I

was really a composer, and before you knew it she had me coming to her home

to take private composition lessons. It’s kind of amusing because

when I was first starting she would call me at home, often on a Saturday

night. She’d say, “Mon petit!”

I was always ‘her little one’! “Mon petit, ce soir à dix heures pour leçon”

[ten o’clock tonight for a lesson]. I learned pretty quickly from the

class that you didn’t say no to that woman! [Both laugh] I wrote

a string trio, and I really don’t remember exactly why, but it was a kind

of a Parisian piece. Different composers develop in various ways.

Some youngsters, maybe because of exposure or teachers or influences at home,

will start off right way with being modern, contemporary. Some who

were eighteen, nineteen, twenty were writing twelve-tone music already.

They’d come out with these esoteric sounds, and you follow that technique

with some intelligence. That at least assures that you going to normally

write tonal music if you’re going to do it correctly. But my approach

was quite a bit different in the sense that I had my various influences such

as Chopin, Schumann, and Schubert. I used to write pieces to imitate

their styles. I was never really all of a sudden a ‘modernist’, but

very slowly I began to evolve a vocabulary. I remember last movement

of that Trio. I wrote it in

one day just walking down a boulevard in Paris. It was a special time

in my life, being young, being in Paris. She said “C’est l’heure pour l’orchestre.”

[It is the hour (to write) for the orchestra.] I never wrote for the

orchestra and she knew that I could! She told me to just dive in, and

when I had questions about it to ask. At least when I came from America

I knew things about orchestration.

I graduated from

De Paul, and I won big scholarships to work with Rudolph Ganz. I learned

with Vittorio Rieti and John J. Becker, and people like that. So I

discovered I really could orchestrate! I wrote a piece called La Joie de la Paix (The Joy of Peace)

because when I went to Europe, my parents and everyone else said, “God,

what are you going to Europe for? The Russians are going to invade!”

My brother was already killed in a war, so there was really genuine concern,

and I was, in a sense, frightened by that. When I got over there I

was much less frightened, but that still was in my head. So I wrote

this piece in relation to being really happy that there hasn’t been any Third

World War, particularly with the Russians. That was inevitable enemy

that was going to race across Poland and Germany and France. Then Boulanger

had it performed by the French Radio Orchestra conducted by Eugène

Bigot. That was quite a big thing for me as a youngster, that I got

that piece performed! The trio that I wrote was done all over France

by a very famous trio in those days called Le Trio Pasquier. Since

that time I’ve got those pieces put away. I don’t allow them to be played

since I think there somewhat immature. They don’t have enough of the

stamp of what I consider my own personality. That came with Adagio Lirico. I have two colleagues

at University, James Tocco, a very famous pianist, and Robert Silverman,

who’s also a famous pianist now living in Canada. That’s why you hear less

of him now, but he has a number of very fine Copland recordings, and also

the Bartók Bagatelles, for

which I wrote the program notes. In any case, Jim Tocco was a pretty

close friend, and he asked me if I had anything for two pianos. I said

no, but somehow he had heard about my Adagio

Lirico. Even though I tried to resist, he demanded to see it.

He said it was the kind of thing that he and Bob like to read through.

So they read through it and liked it, and they decided to play it.

That’s how it started, and it was Jim Tocco who suggested it to the Paratore

brothers.

Getting back to

Nadia Boulanger, the next year my Fulbright was renewed. Darius Milhaud

was coming because he would come only every second year, and I decided that

I was going to study with him because my old teacher in the United States,

Vittorio Rieti, said I ought to because he’s a great cosmopolitan figure.

What made that logical to me was the fact that most of Nadia Boulanger’s

students had what was a very distinct neo-classical vocabulary under her.

She was very, very, very fond of Igor Stravinsky, and particularly his neoclassical

period after The Rite of Spring

and The Firebird and Les Noces, the pieces from the 20s.

I didn’t want to write any of that bi-tonality, but I was happy to work with

Milhaud because I learned a different perception and perspective with him.

At first Nadia was very upset with me. She righteously felt that she

did a lot for me, and I was coming along. I don’t blame her for that

one bit, but I must say she was really a grand lady because later she was

on those juries at the Conservatory, deciding whether I would make it or

not. She was always extremely a Lady in the best sense of the word,

and we remained friends. I remember taking trips back to Paris to the

Fontainebleau Palace. It was a really unforgettable experience.

BD: You must

have made some kind of an impression on Paris, too, because you’ve been

made Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et

des Lettres.

JD: That’s

right. I spent a good number of years there. I did my doctorate

there, and so in a sense politically it was a bad move to have left Nadia

Boulanger. I’ve described just two performances she got me, very crucial

ones. Milhaud didn’t do that sort of thing. He had so many

good students and he didn’t operate that way, helping to get your music

published. You’ve got to get your own performances and sort of thing.

He’d be helpful, but he wasn’t that pushy-type. Boulanger was very

pushy, but she was concerned generally about seeing that you made the right

contacts.

* *

* * *

BD: You’ve

been talking about the way you learned how to write music. Is this

the kind of thing that you are now passing onto your students?

JD: Oh, I hope so, yes. Milhaud had a lot

of great people studying with him, and some of them became great. The

most notable example was Karlheinz Stockhausen. He is a very great

composer, and has a fine track record, but for one reason or another he

just couldn’t pass the exam to get into the Conservatory in the French section.

There may have been an awful lot of factors that no one really knows about,

because they would only allow two foreigners in any given year to be in

that whole section. Maybe for one reason or another it was filled,

but the story that Milhaud told was that Stockhausen really couldn’t hear.

He played the intervals and chords and so on a piano. He had to write

and I’m sure he had no trouble with that, but he didn’t get in. He

was sort of strange... But I remember when I came back to the United

States and when I began teaching, a number of times I had to make a real

soul-searching decision... When a young person comes to you and they

want to know if they really gifted to pursue composition or not, you’re supposedly

a professional and you have to say something, and you can’t just dodge issue.

But on the other hand, what is the basis on which you make that decision?

I always remember that striking story about Stockhausen, who is really a

first rate composer. One may disagree with him stylistically, but at

least he shows great imagination in his works. He’s very avant-gardish

and always has been, but he’s also a real true creator and innovator.

JD: Oh, I hope so, yes. Milhaud had a lot

of great people studying with him, and some of them became great. The

most notable example was Karlheinz Stockhausen. He is a very great

composer, and has a fine track record, but for one reason or another he

just couldn’t pass the exam to get into the Conservatory in the French section.

There may have been an awful lot of factors that no one really knows about,

because they would only allow two foreigners in any given year to be in

that whole section. Maybe for one reason or another it was filled,

but the story that Milhaud told was that Stockhausen really couldn’t hear.

He played the intervals and chords and so on a piano. He had to write

and I’m sure he had no trouble with that, but he didn’t get in. He

was sort of strange... But I remember when I came back to the United

States and when I began teaching, a number of times I had to make a real

soul-searching decision... When a young person comes to you and they

want to know if they really gifted to pursue composition or not, you’re supposedly

a professional and you have to say something, and you can’t just dodge issue.

But on the other hand, what is the basis on which you make that decision?

I always remember that striking story about Stockhausen, who is really a

first rate composer. One may disagree with him stylistically, but at

least he shows great imagination in his works. He’s very avant-gardish

and always has been, but he’s also a real true creator and innovator.

I would get students

occasionally who would have the perfect pitch, or who’d have virtually photographic

memories, really gifted people! We’d have the most interesting discussions

in a composition lesson, and we would start a piece, whatever it was, usually

a song with accompaniment or a violin sonata. The person would bring

in three measures, and we would discuss the potential of those three measures

and various possibilities and procedures. The next lesson, the person

would come, still undecided really about which path to go down, and we’d

really need to discuss this more. Then this would sometimes go on for

six or seven weeks. Pretty soon three measures might go to five measures,

with a great deal of thought about how each note was related to another note,

and so on. But I perceived that this student may, for all the intelligence

that he had, just didn’t have that creative ability. Ninety or ninety-five

per cent of the musicians who are instructed in music could start a piece,

come up with a few measures, but then only maybe fifty per cent could come

to the middle of a piece. Then when you get to actually aiming at

a conclusion in a reasonable logical satisfying manner, then you reduce

that percentage to maybe five per cent. It’s amazing. It sounds

simple, almost simple-minded what I’m saying, but even among that five or

ten per cent that makes it to the end of a piece there’s higher level of

criteria. Is that piece really valuable, or is it good, and so on.

You get a lot of people who can write pieces from beginning to middle and

end, but then does it have some personality? I’ve also had students

who I swear didn’t seem to be able to hear even basic intervals at first,

couldn’t play any instrument, but they were just dying to compose. So

my recipe has been before you really study composition, you have to take up

all the other courses to prepare you for harmony, counterpoint and form, and

orchestration, and so on along that road. If they really survive and

if they’re serious, then they’re going to make it. I have discovered

on a few occasions that people who by European standards would have eliminated.

Maybe they would not have to take up plumbing, but study double bass and maybe

get a position in the orchestra. But to my astonishment and great pleasant

surprise, a couple of students that I have nourished that way have turned

out to be really creative and really gifted. Two of them are really

doing quite well in a composition way. So the moral is it’s astonishingly

difficult to really predict who is genuinely going to make it in a creative

field like composition. A lot of people are gifted with a fine ear

and a good mind, but sometimes they don’t know what’s going on in a piece.

They sit down at the piano and can play it through by rote. If they

have those gifts, maybe they’re going to be a fine performer, but creativity

is something a little bit more nebulous.

BD: When you’ve

created a piece, gone through the beginning, developed the middle and brought

it to a conclusion, how do you know when you’ve finished, that it’s ready

to go out into the world?

JD: That’s

a ticklish problem. Instinctively you kind of know when the piece

is more or less finished, but there’s a very distinct difficulty in conjunction

with putting a convincing ending on what should be there. I will give

you an example — Edge

of Space that I wrote for bassoon and orchestra. I ended on

a high B natural, alone, just the solo instrument. It comes out of

a long orchestral maze. It’s a rather unusual way to end a piece, but

it seemed to me right at the moment. When it was first heard, a number

of people asked me if that was the end of the piece, and why did I end it

that way? They wondered why there wasn’t a big run up and down the

instrument like a big virtuoso gesture. It just seemed right to me

at that particular moment, and you do what you feel is right.

BD: Do you

ever go back and then revise scores?

JD: Not too

much. If for any reason I have to take mistakes out of a score, it’s

almost like a disease what I’m about to describe. When I get one of

my scores to correct what is an obvious mistake — maybe

an instrument is playing a wrong note, or I have really notated categorically

a wrong articulation — I usually end up looking at

the piece, and I get new ideas about it and I start rewriting. That’s

a very dangerous tendency, and I try to really avoid doing that when I can.

BD: You’d be

better off writing a new piece?

JD: Write a

new piece, yes! Once I start reworking something, for whatever reason,

I tend to really redo it. If I were to take one of those earlier pieces

and fix it up for my tastes now, I would probably pretty well rewrite it,

and it would lose whatever charm or vitality it initially had.

BD:

I assume you have quite a few commissions?

BD:

I assume you have quite a few commissions?

JD: Yes.

BD: How do

you decide which commissions you’ll accept and which commissions you’ll

decline?

JD: That’s

a difficult question. The first factor that is terribly important

is whether the commission is intriguing. Does it really challenge you

and whet your appetite and stimulate you to a want to do this thing?

For example, this double bass concerto. I know instinctively that it’s

a real tough combination to work for, and probably I’ll never get too much

mileage out of that piece. First of all there won’t be too many players

like Gary Karr to play it. That piece is very difficult and to get

a double bass to solo with an orchestra has got to be quite difficult.

BD: On the

other hand, if you write something to expand the very small literature for

the double bass, almost anyone who comes to that instrument is going to want

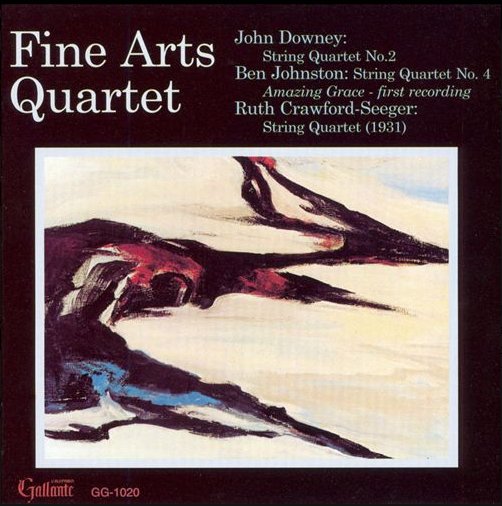

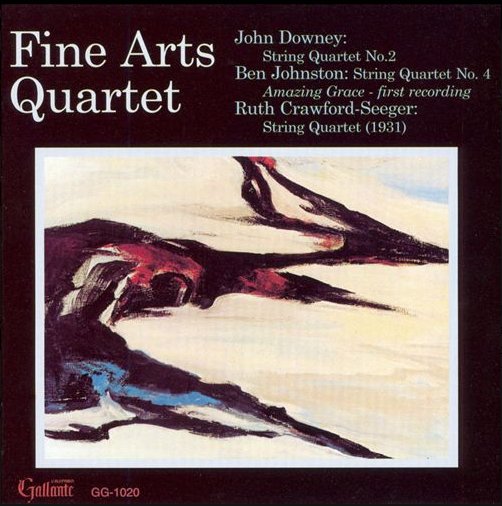

to play it! [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my

interview with Ben Johnston.]

JD: Right.

I know with my Edge of Space, the

Polish composer, Panufnik, heard that record, and on that basis contacted

the bassoonist, Robert Thompson. They worked out a deal whereby he

wrote him a piece for bassoon and chamber orchestra, and maybe in a way expanded

a bit the limited repertoire. So my work had the nice off-shoot of

at least stimulating one other piece that I know about, and Panufnik was nice

enough to let me know. So that was nice, although I just can’t get

my piece performed any place. [Sighs] I’ve never been performed

by the Chicago Symphony either, which is a bit ironic. For whatever

reason, it just hasn’t happened.

BD: Is that

a goal that you have?

JD: Oh sure.

It would be hypocritical to say I wouldn’t desire that. I used to usher

at Orchestral Hall as a boy, and I’ve gotten performed in Paris by several

orchestras and recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra.

BD: Are you

basically pleased with the recordings that have been made of your music?

JD: Yes and

no. I’m so happy that things have gotten recorded because it means

a lot of exposure. For example, somebody from New York told me two days ago

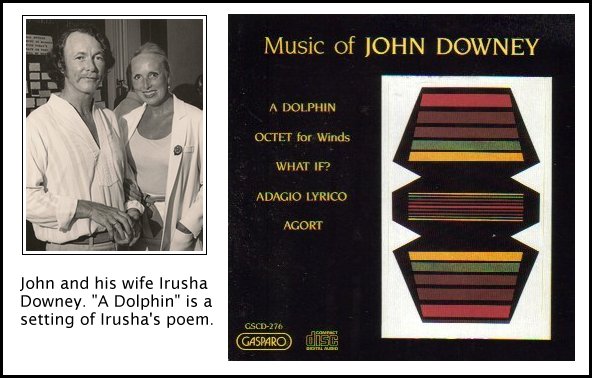

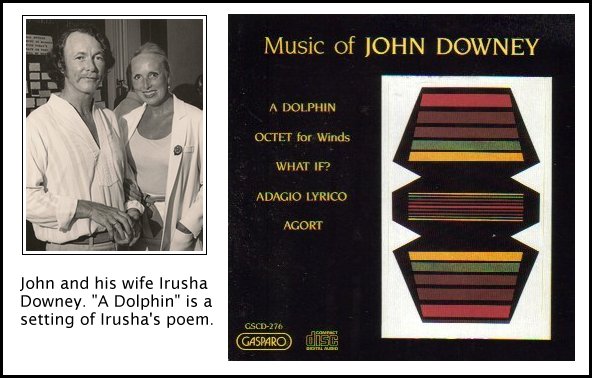

that they heard A Dolphin played

at 10 o’clock in the evening. The music is played in lots of places

that I don’t even suspect. I just don’t know about it, and that’s nice.

It’s how to build up your reputation. But I prefer, when possible,

to have the music done live of course. Earlier I was speaking about

reviving and revising pieces. The quintet Agort was done and now I have a different

order of the movements, which is very peculiar, isn’t it! The recording

was done years ago by The Woodwind Arts Quintet, and they continue to play

that piece. I ended on the recording with that very slow andantino movement, which is very reflective.

Then one time when I was jogging I was just reflecting, and there was a big

performance coming up in Chicago on a program of my music at DePaul University.

I have a very tour de force fourth movement on that recording. When

you hear it, it’s like an internal machine. It goes with all these

quintuplets, and in fact it might be more satisfying to end with that and

put the slow movement in the middle of the piece. So I reshuffled, and

it really works better. I was amazed. Another person told me

that one of the movements is used in New York on WNYC like a theme song for

a show! I’m flattered about that.

* *

* * *

BD: You’re

also a pianist.

JD:

Yes.

JD:

Yes.

BD: Are you

the ideal interpreter of your music?

JD: No!

Good heavens, no! I had my string quartet recorded with the Fine Arts

Quartet. The owner of that record company liked me and he liked my

string quartet, and he learned that I was a pianist. James Tocco had

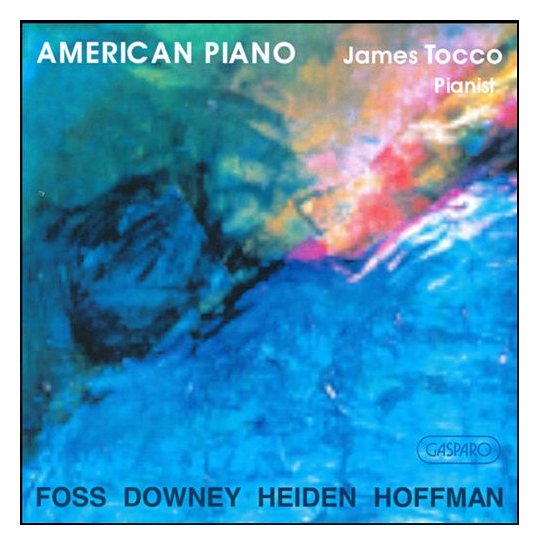

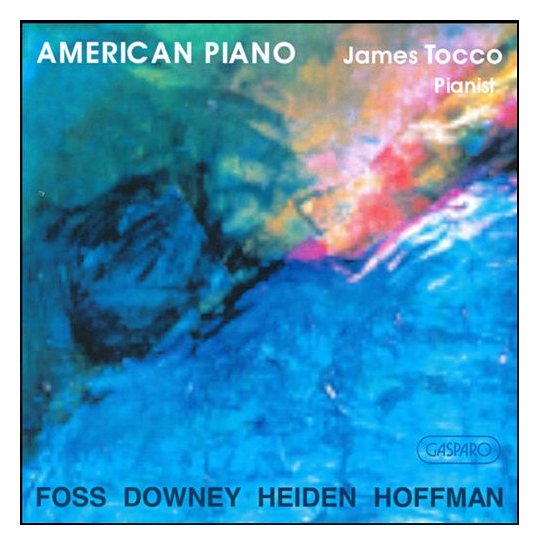

recorded a piece of mine called Pyramids

on that same label, together with some new music by Lukas Foss and Bernhard Heiden.

Tocco, for example, plays that piece like I could never play. He actually

wanted to do all my piano music when he made that recording, but the owner

proposed to me an album on which I would play the piano. I said it

sounded like a good idea, but I couldn’t do Pyramids. He said that was OK since

he had it with James, but he wanted to have a document with me playing some

of my music while I was still playing. So I did it, and that is how

John Downey Plays John Downey came

to be. Later, when I heard that the record was actually going to come

out, I phoned him up and said, “I’ve been playing these

pieces recently and I can do them so much better. In fact, I have a

different ending to Edges.

May I do it over again?” He absolutely refused.

I was hurt and angry at first, but he said, “John,

we’re not really interested in how well you play the pieces, or whether

you add a few notes here and there. We’re just interested to have

some kind of document that there is John Downey playing John Downey’s music.

Let others do it later. They’ll play it better than you. I probably

won’t be making big money selling your records. I didn’t do it for

that. I just want to have the document.”

BD: Is there

any way that records can become too perfect by the time they splice them

up?

JD: Oh yes,

that can happen, particularly if you’re a bona fide virtuoso.

BD: Might they

edit the life out of it?

JD: This is

what I referred to initially with my cello sonata. Although it’s a

great recording, I still remember what great fun we had with the live performances

that piece. Both the pianist and the cellist didn’t care so much whether

they hit a wrong note here and there, but it was the sweep. When they

came to record it, it wasn’t a long drawn out recording. I think they

did it in one session. They played through the piece a couple of times,

but they were both very careful to choose the versions in which all the notes

were played as accurately as possible. That didn’t bother me a bit

because I knew in actual performance there was that big sweep, and that is

somewhat curtailed on the recording. But still, not all that many people

play my music. Here I am in Milwaukee. I’m not in New York or

Los Angeles or Paris or London, and it is a fact that I love my teaching

post. I’m thankful to the University for that, but it’s not on the

main track of where people come from. Chicago is much more of a port

because I grew up there, and when I came back from France I was living in

Chicago for several years before I came up here. I would get visits

from particular people from Paris every year. They would just sleep

on the floor, but there was I right in Chicago, and they were staying a couple

of days before going on to another city.

* *

* * *

BD: Is the

act of composing fun?

JD: It’s my

source of life, the continuation of life. Without it I don’t know what

I would do. I’d be really lost and I would be really isolated.

Composition makes you appear isolated to others because you’re always alone

in silence. When I write I don’t listen much to music. I try

to just hear what’s in me, whatever that means, but I don’t play the radio.

I’ve got my speakers all over, and it’s amazing that I don’t listen that

much now. That’s where the live situation comes in, and I must say

that here in Milwaukee, to hear interesting contemporary music there isn’t

very much of it. Unfortunately, our radio stations at present are really

unimaginative. They are so conservative it is unbelievable. The

moment they put on a contemporary music composition, like they feel all

their clientele is going to stop sponsoring the programs. The only

times that you’ll hear it is maybe when they broadcast the New York Philharmonic

or the Cleveland Orchestra and they have something contemporary. My

records are never played in the city. It’s just terrible, and it didn’t

use to be that way.

BD: Despite

this, are you optimistic about the whole future of music?

JD: Oh, yes! One can always be a curmudgeon

about what’s going on, and I complain a lot, I suppose, but despite that,

I am optimistic. When LPs came on the market, everyone said it’s going

to kill all the orchestras. Then stereo came and that’s going to kill

live music by making records so realistic. Then came the electronics,

and the synthesizer was just going to displace the orchestra. Now it’s

computers. That’s the answer! I follow all that stuff,

and I’ve done a computer piece. I’ve done a couple of pieces for electronic

equipment so I can keep up with the youngsters at the University, so I know

what’s going on! But it doesn’t really change what makes a good piece,

or what makes a real live reaction between an audience and musicians performing

music. There’s still a kind of a magic to that. It’s like a

perennial flower. You know there’s constant obstacles as to what the

weather may be, but it still sprouts up again. It renews and rejuvenates

life, and that is beautiful. That’s why here in the United States it’s

such a beautiful thing that we have these symphony orchestras. The

danger is that you get so many conservative people. It doesn’t necessary

mean that a European has equivocated with anti-American, but often they

just don’t know conductors. A conductor who has grown up in the United

States sees a young composer making illusions to jazz or to rock in his

music, and he’s going to be more receptive to that, and acknowledging that

there is more here than the European conductor who has had no exposure to

that and dismisses it.

JD: Oh, yes! One can always be a curmudgeon

about what’s going on, and I complain a lot, I suppose, but despite that,

I am optimistic. When LPs came on the market, everyone said it’s going

to kill all the orchestras. Then stereo came and that’s going to kill

live music by making records so realistic. Then came the electronics,

and the synthesizer was just going to displace the orchestra. Now it’s

computers. That’s the answer! I follow all that stuff,

and I’ve done a computer piece. I’ve done a couple of pieces for electronic

equipment so I can keep up with the youngsters at the University, so I know

what’s going on! But it doesn’t really change what makes a good piece,

or what makes a real live reaction between an audience and musicians performing

music. There’s still a kind of a magic to that. It’s like a

perennial flower. You know there’s constant obstacles as to what the

weather may be, but it still sprouts up again. It renews and rejuvenates

life, and that is beautiful. That’s why here in the United States it’s

such a beautiful thing that we have these symphony orchestras. The

danger is that you get so many conservative people. It doesn’t necessary

mean that a European has equivocated with anti-American, but often they

just don’t know conductors. A conductor who has grown up in the United

States sees a young composer making illusions to jazz or to rock in his

music, and he’s going to be more receptive to that, and acknowledging that

there is more here than the European conductor who has had no exposure to

that and dismisses it.

BD: Is this

‘composer-in-residence’ idea a good thing? Will it help to get more

contemporary music into the orchestras?

JD: Yes, definitely.

That’s John Duffy’s

program. He has your surname with a different spelling! [Both

laugh] But he’s really a magical individual because he’s made that work,

and I have nothing but praise for him. I met him a few times.

I’m not the composer-in-residence anymore, but the program is beautiful because

it does allow young American composers to be, first of all, active in a relationship

with the orchestra because they’re commissioned to write pieces that the

orchestra is obliged to perform. So that’s already a big step forward.

Then those composers-in-residence can act as a springboard, as a contact

between the conductors and the orchestras and what goes on creatively.

Usually a composer-in-residence knows the other composers. Sure there’ll

be some factors that will occur, but that is always so. Human beings

are human beings. I don’t believe in this puritanical approach like

you get in politics where everything has to be so pure. Life isn’t that

way. People are people, and one helps a friend. That’s not only

happening, but it should happen. That’s what life is all about.

One extends a hand to one with whom you feel some kind of kindred relationship.

That’s normal. What makes a people strong is the sense that there is

something individual about the various groups, and different families carry

different traditions. It’s a healthy situation. Muti [then Music

Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra] now has a composer in residence to

really make him aware of what might be good and meritable in terms of exposure

through the orchestra. Those are good gestures. We don’t want

to have one here in Milwaukee yet, but we have had up until now conductors

who are very, very aware of contemporary music. Kenneth Schermerhorn

introduces a lot of new pieces here, including my own music. All my

music used to be premiered by the Milwaukee Symphony. I had a big

piece, Modules for orchestra, and

that was given for the first time here. Then my Edge of Space was done here. There

Foss came as conductor. He’s a composer, and he knew me as a composer

before he even had the orchestra, so he did my Modules, and he just did a new piece of

mine in New York called Discourse

for oboe with harpsichord and string orchestra, which is going to be done

in Chicago next year by a good conductor, Frank Winkler. But in any

case, now we have another conductor, Zdenek Macal. He’s

Czech, and he probably doesn’t know too much about Americanism. I’m

having my 60th birthday October 5th, and here at the University they’re organizing

a big program of my music, which is nice because I didn’t expect that or

ask anyone. Then this summer I’m going have a piece called Declamations which was premièred

in Albany, New York with that orchestra. The Music for Youth Orchestra

did it here last May, and then it was done in Paris in November by conductor,

Roger Boutry. Now, Music for Youth is going to take that on tour

with it this summer. I don’t know yet exactly where, but they’re going

to perform in Switzerland, Austria, Germany and France. So that’s good.

Then I hope I get to Australia for the premier of my double bass concerto

because I would like to hear that very much. That’s kind of exciting.

It’s always nice to hear your music played, but it’s especially exciting

when you know it’s a piece that no one has played yet, no one has heard.

BD: When you’re

working with an orchestra on a new piece, do you go with suggestions, or

do you let them get on with the work and find out what’s there?

JD: It depends.

I think the best approach is for the composer to keep somewhat of a low profile,

provided the conductor’s competent. That’s important. But let’s

assume you’ve got a good conductor. They’ve taken the piece and they’re

going to give it their best shot because they want it to succeed, too.

Probably a very vociferous composer who starts telling the conductor everything

that’s going wrong right at the first unveiling of the piece makes a tremendous

mistake for two reasons. First of all, if you just let the musicians

go through it, they can feel their way in. This includes the conductor.

Once they know what’s there, then they can go back and rework it.

You have to be patient. The only thing I find I need to do is when

the conductor turns around and says, “Is that really

supposed to be E-flat up in the flutes there, or is that supposed to be a

D-flat?” You had better know your score

which you’ve written, or else you look like a dummy. Typically the

conductor turns around and says, “Is this tempo right?

Does this feel right what I’m doing here?” You

might say that it’s a little fast or a little slow. Things like that

I think are valid, but to go up and pull the guy by the arm every two measures

and saying, “You don’t know my music! You don’t

understand what I’m trying to do! They’re playing it all wrong!”

is a poor approach. But that’s usually the temperament of the young

composer.

BD: They want

everything right the first time!

JD: That’s

right. Another interesting thing that has happened to me, so I speak

from experience, is that those piece which are so fragile that they only

work a certain way are usually weak pieces. They’re not yet very mature.

They don’t bend.

BD: Being sturdy

is another indication of a good piece?

JD: This is

another indication of a good piece, when it piece allows for different ideas.

I have a piece for piano called Eastlake

Terrace. It’s one of my favorite pieces, and Eastlake Terrace

is very near where you live!

BD: Yes, it is.

I drive on it quite often!

JD: That’s

on John Downey plays John Downey.

Anyway, I have heard it played in countless ways, really stretching my tempo

marks and everything, and it still works. That’s one of the things

that made me realize Oh God, that’s a good piece!

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the home of John Downey in Shorewood,

Wisconsin, on June 1, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB four months

later, and again in 1992 and 1997, on WNUR in 2011, and on Contemporary Classical

Internet Radio in 2010. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted

on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry for her help

in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until

its final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various

magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues

his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

JD: I think that’s probably true. There’s

a certain advancement in terms of chromaticism, and the next logical step

in his period had to be something beyond what Wagner had already accomplished.

It wasn’t just Wagner, but he’s probably the principle innovator of his time

for the use of non-stop melodic lines and a tremendous sense of orchestration

that he had. As you say, if he hadn’t done it somebody else would have.

Today, after a lot of twelve-tone meandering all the way up to pre-determined

music and the intellectual approach, I noticed as a teacher in composition

that young people just really didn’t want that. You kind of shove

that down their throats as part of the technique everybody has to know,

but in the 1950s and ’60s, that was still pretty much

in a vogue in this country. But as you get into the 1970s and particularly

the ’80s, that is no longer a firm procedure that

most every young composer adopts. All young composers are exposed

to it, but you have a much greater diversity, especially since ‘minimalism’

came in such vogue. People like Philip Glass and

Steve Reich, and particularly

John Adams — who combines a lot of other things in

it — give you more of hook up with traditionalists.

Composers are on a different road now. Probably the most influential

composer in this country in a populist theme was George Crumb. His

pieces are exceedingly dramatic. They’re very mystic in so far as he

has a lot of other than strictly musical forces working on his pieces.

But they’re not just strict, turgid, at the mercy of one particular technique.

JD: I think that’s probably true. There’s

a certain advancement in terms of chromaticism, and the next logical step

in his period had to be something beyond what Wagner had already accomplished.

It wasn’t just Wagner, but he’s probably the principle innovator of his time

for the use of non-stop melodic lines and a tremendous sense of orchestration

that he had. As you say, if he hadn’t done it somebody else would have.

Today, after a lot of twelve-tone meandering all the way up to pre-determined

music and the intellectual approach, I noticed as a teacher in composition

that young people just really didn’t want that. You kind of shove

that down their throats as part of the technique everybody has to know,

but in the 1950s and ’60s, that was still pretty much

in a vogue in this country. But as you get into the 1970s and particularly

the ’80s, that is no longer a firm procedure that

most every young composer adopts. All young composers are exposed

to it, but you have a much greater diversity, especially since ‘minimalism’

came in such vogue. People like Philip Glass and

Steve Reich, and particularly

John Adams — who combines a lot of other things in

it — give you more of hook up with traditionalists.

Composers are on a different road now. Probably the most influential

composer in this country in a populist theme was George Crumb. His

pieces are exceedingly dramatic. They’re very mystic in so far as he

has a lot of other than strictly musical forces working on his pieces.

But they’re not just strict, turgid, at the mercy of one particular technique.

BD:

Do you decide to become a composer, or is this thrust upon you?

BD:

Do you decide to become a composer, or is this thrust upon you? BD: And yet it’s not something you want to go

back to and tinker with to bring up to date?

BD: And yet it’s not something you want to go

back to and tinker with to bring up to date? JD: I think it’s wrong. I agree with you

totally. I’ll give you another example.

As a student, a youngster in Paris, I was amazed that I got admitted to

the French section of the Conservatoire. That meant that each year

your exams were to follow. You didn’t get graded like here, where

you get an A or a B, or a C, or a D for every class. It doesn’t work

that way in France. You either got a prize or you didn’t. I

was working on one composition for a given year, and at the end of the year

that piece had to be presented before a jury who would decide whether that

piece looked like it had some potential or not. If it did, then the

next step would be to have it played by the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra

— which is a damn good one, so you got good performances.

Maybe you’d be passed academically by the Board, but there were some real

lemons. But you learned, and you were given usually a limit of just

a few years to get the prize. You could still compete and gain experiences

each year from these performances. You might even get a ‘second prix

de composition’ which would give you another four or five years.

JD: I think it’s wrong. I agree with you

totally. I’ll give you another example.

As a student, a youngster in Paris, I was amazed that I got admitted to

the French section of the Conservatoire. That meant that each year

your exams were to follow. You didn’t get graded like here, where

you get an A or a B, or a C, or a D for every class. It doesn’t work

that way in France. You either got a prize or you didn’t. I

was working on one composition for a given year, and at the end of the year

that piece had to be presented before a jury who would decide whether that

piece looked like it had some potential or not. If it did, then the

next step would be to have it played by the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra

— which is a damn good one, so you got good performances.

Maybe you’d be passed academically by the Board, but there were some real

lemons. But you learned, and you were given usually a limit of just

a few years to get the prize. You could still compete and gain experiences

each year from these performances. You might even get a ‘second prix

de composition’ which would give you another four or five years.  JD: Oh, I hope so, yes. Milhaud had a lot

of great people studying with him, and some of them became great. The

most notable example was Karlheinz Stockhausen. He is a very great

composer, and has a fine track record, but for one reason or another he

just couldn’t pass the exam to get into the Conservatory in the French section.

There may have been an awful lot of factors that no one really knows about,

because they would only allow two foreigners in any given year to be in

that whole section. Maybe for one reason or another it was filled,

but the story that Milhaud told was that Stockhausen really couldn’t hear.

He played the intervals and chords and so on a piano. He had to write

and I’m sure he had no trouble with that, but he didn’t get in. He

was sort of strange... But I remember when I came back to the United

States and when I began teaching, a number of times I had to make a real

soul-searching decision... When a young person comes to you and they

want to know if they really gifted to pursue composition or not, you’re supposedly

a professional and you have to say something, and you can’t just dodge issue.

But on the other hand, what is the basis on which you make that decision?