A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

Conductor, trumpet virtuoso, and composer Stephen Burns has been

acclaimed on four continents for his consistently and widely varied performances

encompassing recitals, orchestral appearances, chamber ensemble engagements,

and innovative multi-media presentations involving video, dance theatre,

and sculpture. Prof. Burns is the founder and Artistic Director of the

Fulcrum Point New Music Project in Chicago. He co-curated with Augusta Read Thomas

the 2016 Ear Taxi Festival of Contemporary Music in Chicago, and is founding

president of its sponsor New Music Chicago.

He began his studies at the age of ten and made his professional debut at the age of 14 performing the Handel Aria “Let the Bright Seraphim” with coloratura soprano Elizabeth Phinney. At 19 he won the concerto competition at The Juilliard School, performing the Jolivet Concertino at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall. In 1981 he was the first solo trumpeter to win the Young Concert Artists International Auditions resulting in debut performances at The Kennedy Center, Carnegie Hall, and The Hollywood Bowl. In 1988 he won First Prize at the Maurice André International Competition for Trumpet in France, which brought him numerous international engagements, including national television appearances and tours of Europe, Asia, South America and the United States. Burns has performed in the major concert halls of New York, Boston,

Washington DC, Los Angeles, Houston, Vancouver, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Paris,

and Venice. He has performed at the White House and has appeared

on NBC’s “Today Show” and NPR’s “All Things Considered.” His European

tours have taken him to Italy, France, Spain, Finland, Germany, Holland,

Portugal, and Switzerland for guest appearances with orchestras, as well

as recitals and performances on radio and television. On tour in

the Far East he won rave reviews, which singled out his remarkable tone,

musicianship, and technical facility. Throughout his career he has

appeared with many leading international orchestras including the Atlanta

Symphony under Neeme

Järvi, The Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra under Iona Brown, The

Ensemble Orchestral de Paris, The Arturo Toscanini Orchestra of Parma, the

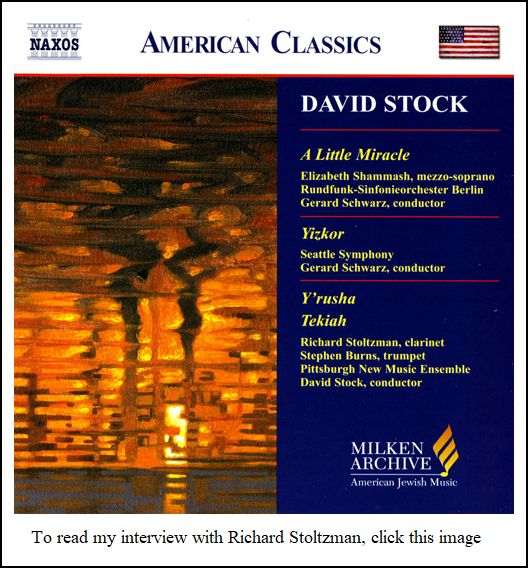

Japan National Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony under Gerard Schwarz, and a

United States tour with the Leipzig Kammerorkester. His recital programs

often feature his own transcriptions of Falla’s El Amor Brujo, Prokofiev’s

Lt. Kijé, and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an

Exhibition, the latter scored for trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn, piccolo

trumpet, bass trumpet, and piano.

In 1998 Burns was invited to create innovative new music programs

as the Artist in Residence with Performing Arts Chicago. In the process

he created the Fulcrum Point New Music Project, and the American Concerto

Orchestra whose mission it is to champion New Art Music influenced and

inspired by Pop culture, World Music, literature, film, art, theatre, dance,

nature, politics, and social dynamics. The annual peace concerts have been

held at the Holtschneider Performance Center at DePaul University, Holy

Name Cathedral, Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park, and The Harris Theater

for Music and Dance. These concerts have featured MacArthur fellow Vijay

Iyer, members of the Gyoto Tantric Monks, and The Ju.Ju Exchange with Julian

Reid and Nico Segal.

A conducting student of Jorma Panula, Gerard Schwarz and Pinchas

Zukerman, Burns often appears as both soloist and conductor with orchestras

performing repertoire ranging from the Second Brandenburg Concerto

of Bach, and Haydn’s E-Flat major Concerto, to works by Copland,

Shostakovitch and André Jolivet. He has performed this dual

role with the Santa Barbara Chamber Orchestra, the Simon Bolivar Orquesta,

the Orquesta da Camera del Tachira, the Sea Cliff Chamber Orchestra, and

the American Concerto Orchestra. As a guest conductor he has performed with

the Aspen Music Festival, the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, the Orquesta

Sinfonica Castilla y León, the Ravinia Festival, and the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra’s “Music NOW” series in Millennium Park.

The founding president of New Music Chicago, Burns has given

numerous premieres by American composers including Ned Rorem, David Stock, Gunther Schuller, Robert

Rodriguez, and Philip Glass,

as well as international names such as Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Franck Amsellem,

Somei Satoh, and Aulis Sallinen. Committed to new music, Burns has

written for trumpet, electronic music, chamber music and symphony orchestra.

In 2007 he was commissioned by the Renaissance Society at the University

of Chicago to write the electro-acoustic version of Reveille, “Wake Up,

Y’all” as part of the Allora/Calzadilla installation “Wake Up.” “Fanfare

for Humanity” was commissioned by the Chicago Humanities Festival for the

2003 opening Gala. His composition “Reflections,” a work created in collaboration

with choreographer Ruby Shang, was performed around the Henry Moore reflecting

pool at Lincoln Center in 1989. At the request of Pipa virtuoso

Yang Wei, Burns wrote the incidental music to “Cat and Rat: the Legend

of the Chinese Zodiac” as part of the Children’s Humanities Festival in

Chicago. He is currently composing “Phalanx,” a multi-media work based

upon American military musical themes.

Burns is a frequent guest artist at many prestigious summer festivals

including Aspen, Santa Fe, Kuhmo, Tanglewood, Mostly Mozart, Spoleto, Caramoor,

Lieksa, Ravinia, Grand Canyon, Moab, Estate Musicale St. Cecilia, and

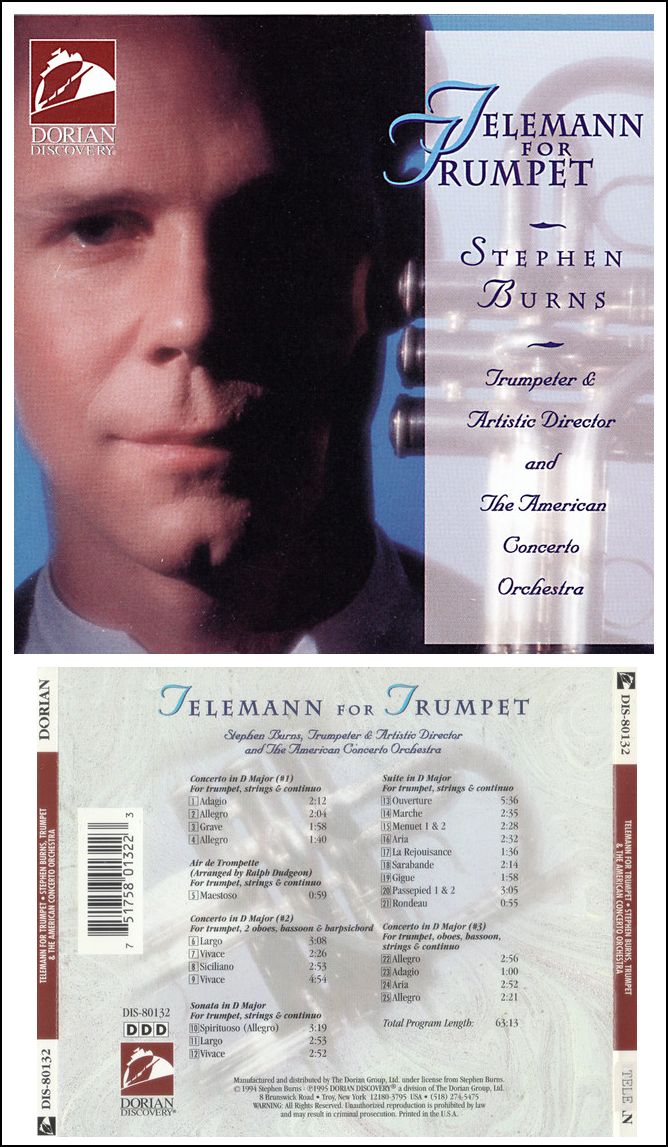

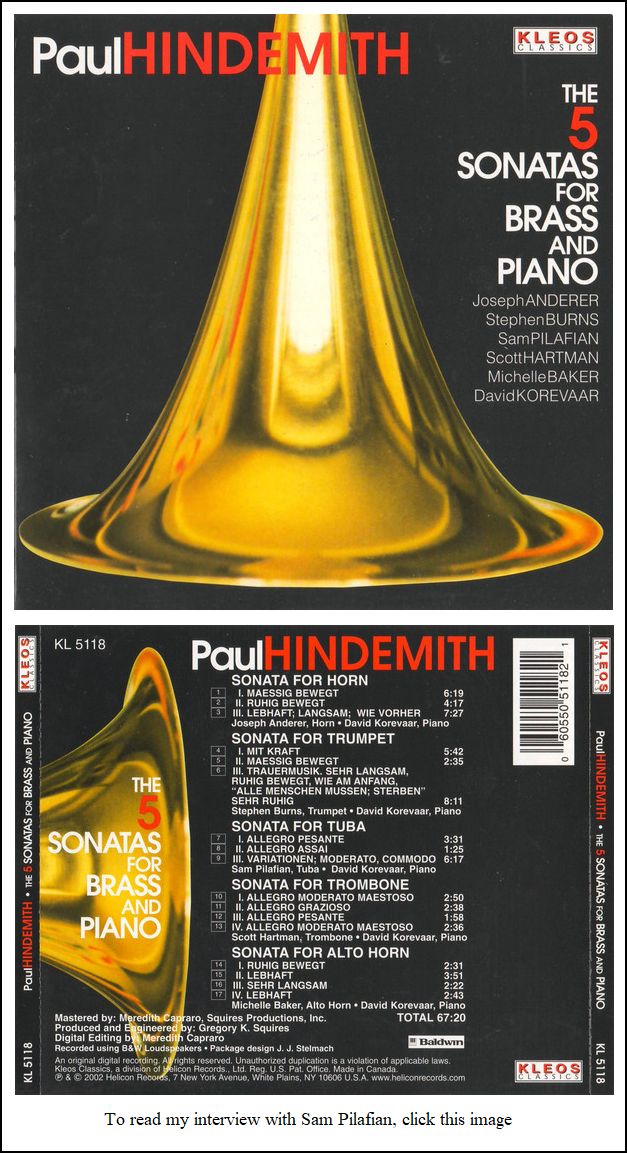

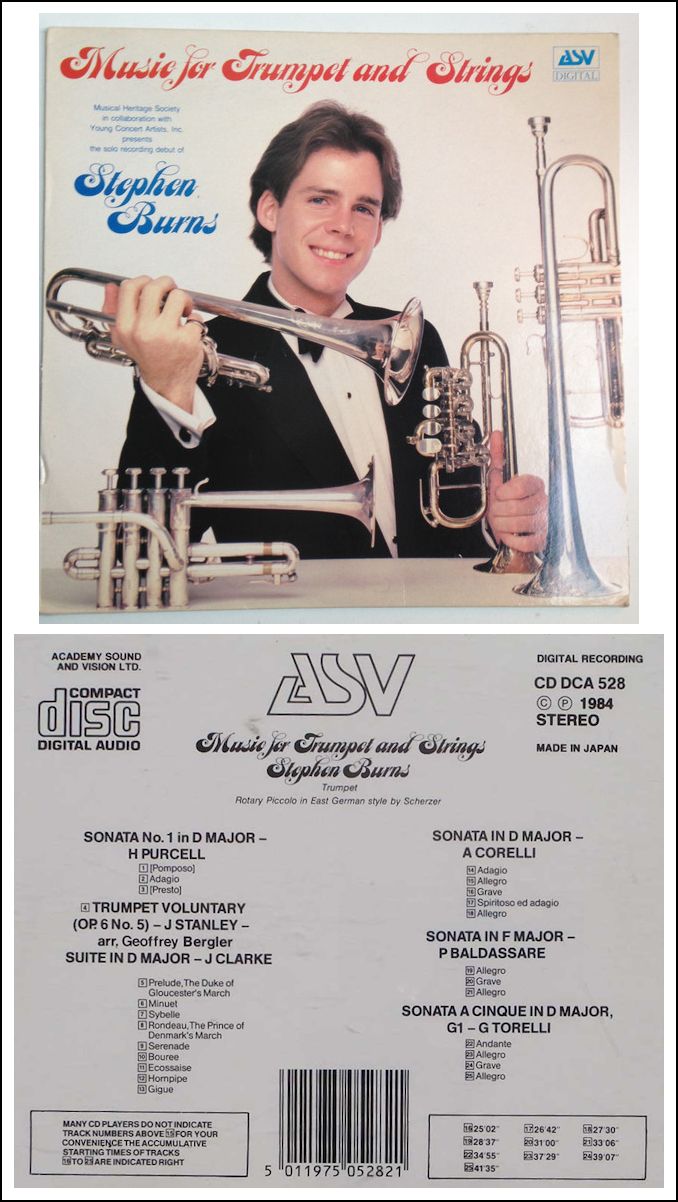

Divonne les Bains. His recordings include Telemann for Trumpet with

the American Concerto Orchestra, on Dorian, The Complete Sonatas for

Brass by Paul Hindemith on Helicon, The Complete Brandenburg Concerti

with Helmuth Rilling

on Haenssler Classics, and Trumpet Voluntary on ASV records. He has

also recorded for Kleos, Musical Heritage Society, Delos, Classical Masters,

Ess.a.y, and Grammavision.

Originally from Wellesley Hills, Massachusetts, Burns studied

under Armando Ghitalla, Gerard Schwarz, Pierre Thibaud, and Arnold Jacobs

at the Tanglewood Music Center, the Julliard School (BM/MM 1981-82), as

well as in Paris and Chicago for post-graduate studies. He has won

many prestigious awards including the Young Concert Artists International

Auditions, Avery Fisher Career Grant, the National Endowment for the Arts

Recitalist Grant, the Naumburg Scholarship at Juilliard, “Outstanding Brass

Player” at Tanglewood, the Maurice André Concours International

de Paris, and the Helen Colburn Meier and Tim Meier Arts Achievement Award.

Sought after internationally for master classes, Burns is on faculty

at the DePaul University School of Music, a certified teacher of The Art

of Practicing and Performing Beyond Fear, a visiting lecturer at Northwestern

University, visiting lecturer with the Amici della Musica Firenze, Italy,

and a former tenured Professor of Music at Indiana University. Burns is

a Yamaha performing artist.

== Biography edited from the DePaul University

website

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

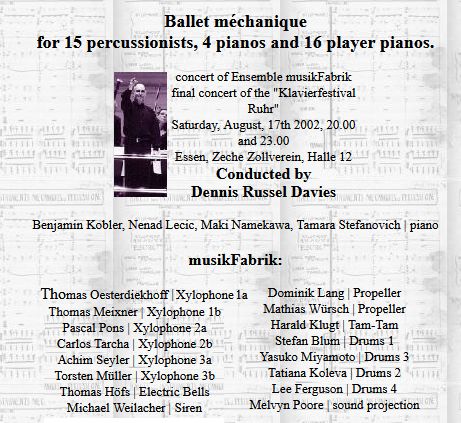

| Ballet mécanique is Antheil's

most famous—or notorious—piece. At its various premieres, it caused

tremendous controversy, not to mention fistfights. Although it was

very successful in Paris, it was a huge flop when it came to New York,

and in fact Antheil's career as a "serious" composer never recovered

from that debacle.

The piece was originally supposed to be a soundtrack to a film of the same name by the French Dadaist painter Fernand Léger and cinematographer Dudley Murphy. But Antheil and the filmmakers worked separately from each other, and when they finally put the music and the film together, they realized they didn't work at all -- for one thing, the music was twice as long as the film. A new version of the film, with—finally—Antheil's music, had its premiere on May 5, 2001. Ballet mécanique is a highly rhythmic, often brutalistic piece combining, among other elements, sounds of the industrial age, atonal music, and jazz. Its instrumental parts are extremely difficult to play, and it lasts, in its various versions, between 14 and 30 minutes.Antheil wrote several versions of the piece. The very first, written in 1924 calls for 16 player pianos playing four separate parts, four bass drums, three xylophones, a tam-tam, seven electric bells, a siren, and three different-sized airplane propellors (high wood, low wood, and metal), as well as two human-played pianos. Until the 1990s, this version of the piece had never been performed in its original instrumentation, since the technology for linking and synchronizing multiple player pianos, whether 4 or 16, although theoretically possible when Antheil conceived the piece, turned out not to be practical. The European-based Ensemble Moderne was the first to attempt the piece: in 1996 and 1999, they performed it in Germany and France using two custom-modified MIDI-driven player pianos to play the 16 parts, and six pianists to play the two human parts. In response to the technical difficulties, Antheil

quickly re-arranged the piano parts, changing the orchestration to

include an unspecified multiple of two conventional pianos and a

single player piano. This version was performed, using 10 human-played

pianos, in Paris in 1926 and in an extremely ill-fated concert at New

York's Carnegie Hall in 1927, where it created such a fiasco--technically,

musically, and sociologically--that it was not performed again for over

60 years. In 1989 it was revived by conductor Maurice Peress for a performance

at Carnegie Hall, and at that time received its first and only recording.

Today, however, we have the technology to perform

the piece with its original instrumentation, and it has now been

done several times. == Text (only) from the Antheil website  \

\

[Portions of three reports of this event]

It went very well! The audiences were enthusiastic (two performances, around 900 people attended each). The propellers and the bell array worked fine, as well as our xylophone configuration and the drums (spread over the whole 22m of the stage, each with different instruments for the 'tone heights' of the score). It was great fun for the 15 percussionists! Horst Mohr, player-piano builder: On Saturday, August 17th, there was a wonderful performance of

George Antheil's "Ballet Mécanique" in a hall of the old coal

mine "Zeche Zollverein", now devoted to world cultural heritage (WeltKulturErbe).

It was the climax and finish of a series of more than 60 concerts

in 9 weeks: "Klavierfestival Ruhr", the world's greatest piano festival.

Art director (künstlerischer Leiter) Franz Xaver Ohnesorg

(now Intendant of the Berlin Philharmonics) devoted this festival to America:

18 of the 88 performing artists came from the USA and Leon Fleisher, famous

American pianist, conductor and teacher was given an award for his

life work. The Ballet was realized in the version Antheil had intended

to perform in 1927 in Carnegie Hall. Conductor Dennis Russell Davies

stands for precision and authenticity. Four hand-played grands, 16

pianolas, much percussion with bells, siren and 3 propellers - all

without any electronic sound. The preparation took nearly a year. Three propeller machines and a set of bells had to be built. About 100,000 notes and accents were transformed into MIDI files, almost all by Dr. Jürgen Hocker, who was in charge of musicological and computer care and control for this concert. The Yamaha Disklavier uprights were collected from all over the country. 14 Disklaviers were positioned in two rows. Dr. Hocker's two Ampico grands stood in front, with the four hand-played grands beside. The percussion instruments were on a long platform above the pianolas. The controlling computer was situated together with the lighting controls on a desk in the auditorium. Very impressive also was the lighting: one spot for each piano and one for every musician. Colored lights illuminated the different phases of the music: for example, when the uprights were playing alone, all other lights were dimmed and only the long row of the uprights' white hammers shone in the darkness, performing chromatic clusters. The synchronization was perfect and the huge chords sounded absolutely together - no trace of fast arpeggios. By the end, the light became bright in the hall and also came in from outside, as the whole building was illuminated. The applause and stamping were overwhelming, and even the many VIPs from the worlds of culture, politics and business clapped hands. George Antheil would have been satisfied! (Thanks to the Mechanical Music Digest for permission to use this material) Dr. Jürgen Hocker, player-piano expert and programmer extraordinaire: Finally all went well with the Ballet Mécanique.

The performances were absolutely great and the sound was really perfect!!

We had two performances, because the first performance sold out months

ago, and so the organizer planned a second performance at 11.00 pm the same

day. The preparations were extremely difficult. There were different files

needed for the [Ampico] player pianos and the different types of

Disklaviers, and Dennis Russell Davies wanted many tempo and dynamic changes

during the piece. For example, since he didn't want any amplification, then

to hear the live pianists, the player pianos had to play fairly soft, but

only when the live pianists were playing. Other times, the player pianos

usually played with full power. Davies tried a proper balance between all

the instruments, and I think he succeeded. But during the rehearsals there

arose a lot of problems. At one point six of the Yamaha pianos stopped

playing. What happened? They were all connected on one cable spool,

and the spool got so hot a fuse cut off the current. Also, during

a pause in the piece one of the Disklaviers begun to play a jazz

piece!! Why? Someone forgot to get out the [setup] disc from

the piano. And nobody knows how it began to play the disc. Another shock:

During the rehearsal only eight Disklaviers played to the finish.

Why? We had two run-throughs of the whole piece (27 minutes each),

and this was too much for the Disklaviers. They got hot and switched

off!! As we had two and a half days of rehearsals, we were able to get familiar

with all the possibilities for failure, and the performance was

great. They had a spotlight for each piano and for each musician.

They built three propellers and a bell arrangement with maybe ten

different bells. We didn't use the Schirmer files [Dr. Hocker created

his own files some years ago], but we used the click track (even that

was slightly modified). == Text and images from the Antheil website

|

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 11, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 2000; on WNUR in 2011; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio also in 2011. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.