Augusta Read Thomas, born in 1964 in Glen Cove,

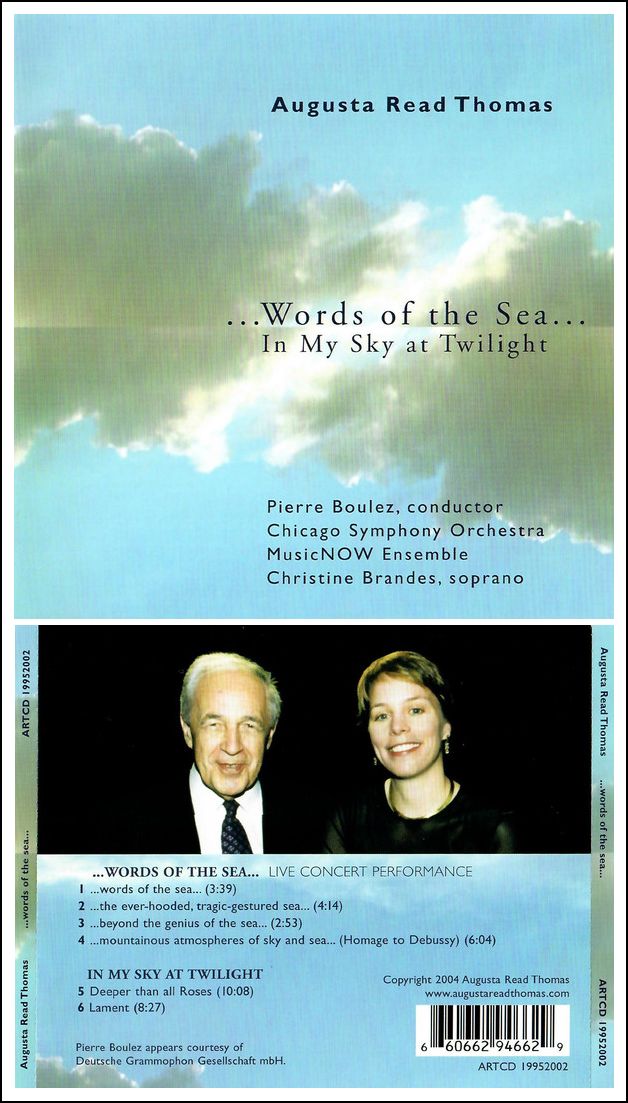

New York, was the Mead Composer-in-Residence for Pierre Boulez and Daniel Barenboim at

the Chicago Symphony Orchestra from 1997 through 2006. In 2007, her Astral

Canticle was one of the two finalists for the Pulitzer Prize

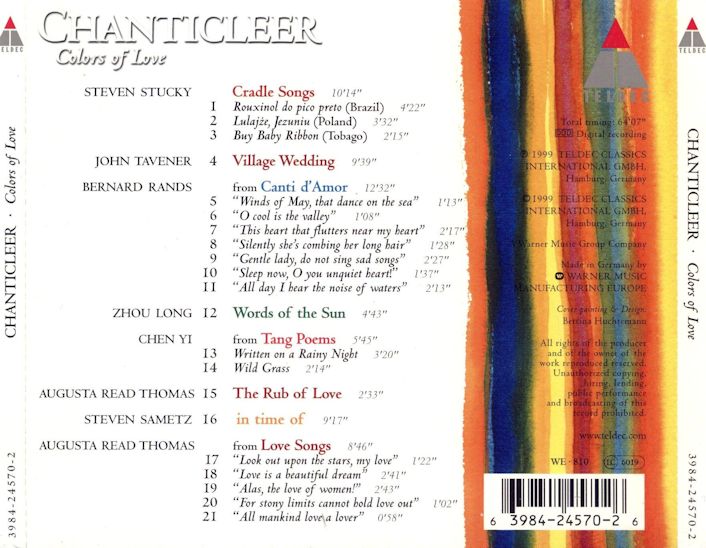

in Music. The "Colors of Love" CD by Chanticleer [shown below],

which features two of Thomas' compositions, won a Grammy award.

Thomas is a member of: the American Academy of Arts and Letters; the

American Academy of Arts and Sciences; the Advisory Committee of the Alice

M. Ditson Fund at Columbia University; the Board of Trustees of the American

Society for the Royal Academy of Music; the Eastman School of Music's

National Council; as well as boards and advisory boards of several chamber

music groups including the Ice Ensemble. She has been on the Board of

Directors of the American Music Center since 2000. She was elected

Chair of the Board of the American Music Center, a volunteer position that

ran from 2005 to 2008. For the 2014-2015 academic year, Augusta was a Phi

Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar.

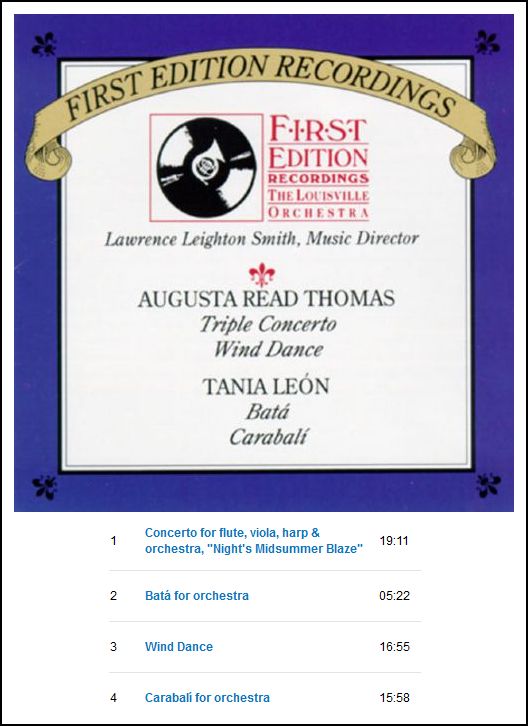

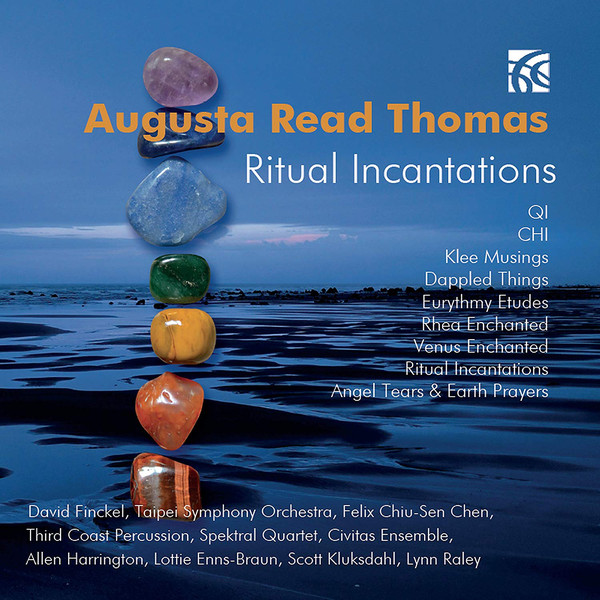

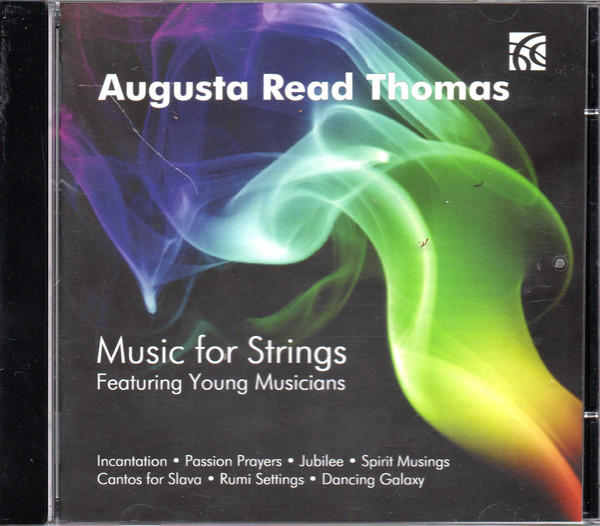

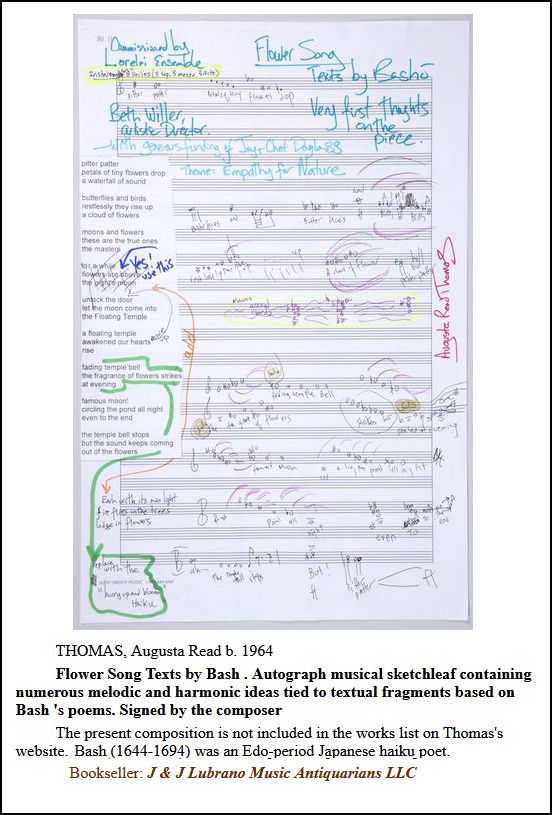

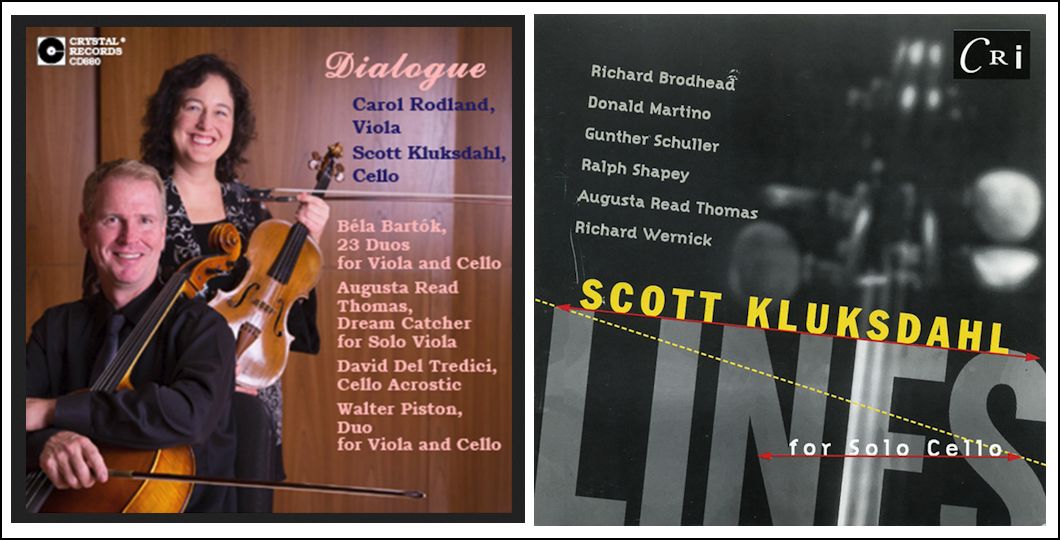

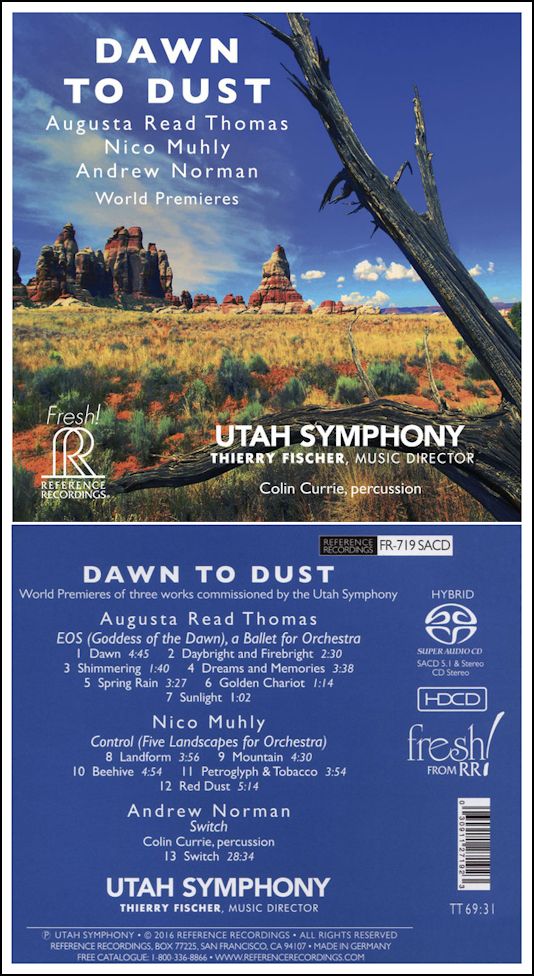

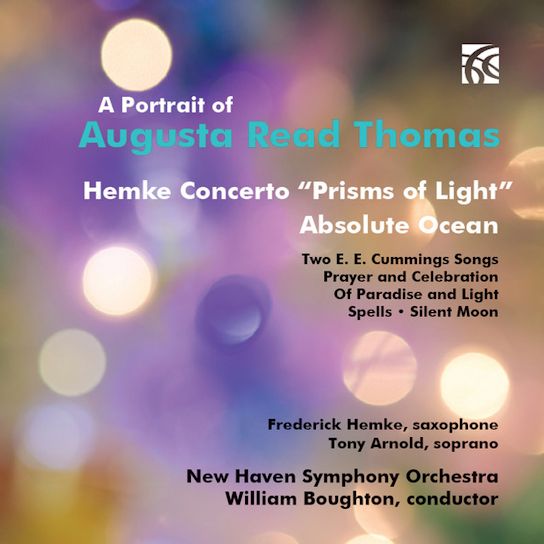

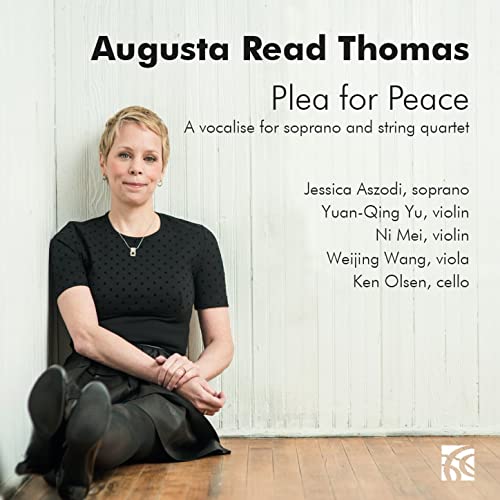

G. Schirmer, Inc. is the exclusive publisher of her music worldwide for all works composed until December 31, 2015. Nimbus Music Publishing is the exclusive publisher of her music worldwide for all works composed after January 1, 2016. Her discography includes 80 commercially recorded CDs.

The Sovereign Prince of Monaco awarded Augusta CHEVALIER of the Order of Cultural Merit. The insignia of this distinction was given by S.A.R. Princess of Hanover at the Prince's Palace on 18 November 2015. Augusta Read Thomas also won the Lancaster Symphony Orchestra's Composer Award for 2015-16. This is the oldest award of its kind in the nation, intended "to recognize and honor living composers who reside in the US who are making a particularly significant contribution in the field of symphonic music, not only through their own creative efforts, but also as effective personal advocates of new approaches to the broadening of critical and appreciative standards."

Thomas played piano as a young child, starting private lessons at age four. In third grade, she took up the trumpet and played for 14 years, attending Northwestern University as a trumpet performance major. She played trumpet in brass quintet, chamber orchestra, orchestra, band, and Jazz band and she sang in choirs for many years.

Thomas was awarded fellowships from the Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College, and was a fellow for three years in the Harvard University Society of Fellows.

Her music, which is regularly performed worldwide, has been conducted by: Christoph Eschenbach, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, Mstislav Rostropovich, Seiji Ozawa, Leonard Slatkin, Oliver Knussen, David Robertson, Lorin Maazel, Sir Andrew Davis, Jiří Bĕlohlávek, Hans Graf, Marin Alsop, Cliff Colnot, Xian Zhang, Andrey Boreyko, William Boughton, Gil Rose, Gerard Schwarz, John Nelson, Joana Carneiro, Hans Vonk, Markus Stenz, Dennis Russell Davies, George Benjamin, Ludovic Morlot, Robert Trevino, Hannu Lintu, Josephine Lee, Michael Lewanski, Bradley Lubman and George Manahan among others.

Thomas received awards from the Siemens Foundation in Munich; ASCAP; BMI; National Endowment for the Arts (1994, 1992, 1988); American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters; Guggenheim Memorial Foundation; Koussevitzky Foundation; New York Foundation for the Arts; John W. Hechinger Foundation; Kate Neal Kinley Foundation; Columbia University (Bearns Prize); Naumburg Foundation; Fromm Foundation; Barlow Endowment; French International Competition of Henri Dutilleux; Rudolph Nissim Award from ASCAP; and the Office of Copyrights and Patents in Washington, D.C. awarded her its Third Century Prize.

Seven years after graduating from the Royal Academy of Music in London, Thomas was elected as Associate (ARAM, honorary degree), and in 2004 was elected a Fellow (the highest honor they bestow) of the Royal Academy of Music (FRAM, honorary degree). In 1998, she received the Distinguished Alumni Association Award from St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire. In 1999, she won the Award of Merit from the President of Northwestern University, and a year later received The Alumnae Award from Northwestern University. Sigma Alpha Iota Music Fraternity initiated her as an Honorary Member in 1996.

Thomas also had the distinction of having her work performed more

frequently in 2013-2014 than any other living composer, according to

statistics from performing rights organization ASCAP.

Bruce Duffie: You have a record

that is coming out soon?

Bruce Duffie: You have a record

that is coming out soon? BD: If she then asks you for another piece, and asks

you to make it a little more jazzy, would you do that?

BD: If she then asks you for another piece, and asks

you to make it a little more jazzy, would you do that? BD: It is even possible ever to

have a performance of a piece of music of yours, or anyone’s, that

is just right?

BD: It is even possible ever to

have a performance of a piece of music of yours, or anyone’s, that

is just right? BD: Who decides if you’re a Composer

— is it you? Is it the public? Is

it the teachers?

BD: Who decides if you’re a Composer

— is it you? Is it the public? Is

it the teachers?

Thomas: Sometimes! Sometimes life just gets out

of control, because I’ve got three pieces at once that I really want

to write in there, and they’re gnawing at me, but I’m traveling for the

next three months, and I have to proofread parts for something, and I’m

teaching full-time, and my husband lives in a different city... When you

stack it all up, life is very, very complicated. Just think of

the airports that I go to every month. It feels like that alone is

a full-time job. So, there’s a lot to keep balanced. The actual

creative side of the music is all encompassing, but I like that about it.

Thomas: Sometimes! Sometimes life just gets out

of control, because I’ve got three pieces at once that I really want

to write in there, and they’re gnawing at me, but I’m traveling for the

next three months, and I have to proofread parts for something, and I’m

teaching full-time, and my husband lives in a different city... When you

stack it all up, life is very, very complicated. Just think of

the airports that I go to every month. It feels like that alone is

a full-time job. So, there’s a lot to keep balanced. The actual

creative side of the music is all encompassing, but I like that about it. BD: Who should judge that

— the public? Other composers? The

critics?

BD: Who should judge that

— the public? Other composers? The

critics? BD: Are you at the point in your career that you expect

to be as you approach thirty?

BD: Are you at the point in your career that you expect

to be as you approach thirty?

Thomas: It’s been fascinating.

I have been collaborating on this opera with a colleague of mine

at Harvard, whose name is Leslie Dunton-Downer. She’s a mediaevalist

by trade, and a very, very bright and successful woman who happens

to be immensely creative. So she has created a libretto for this

piece, and it’s been a fantastic collaboration, and very intense.

We’ve made a lot of revisions together, which is good. I feel

all of our revisions have made the piece better. We work very well

together, and I find it very nice to work with a woman. We seem

to be able to communicate, and find time where we can both work.

It’s a good situation. So, that whole side of the project has been

phenomenally interesting. It was commissioned by Mstislav Rostropovich,

and it’ll be premiered in May of 1994 in France

— which is very soon in the opera world. It’s

thrilling because I made it for him, and he’s given me so much time.

Thomas: It’s been fascinating.

I have been collaborating on this opera with a colleague of mine

at Harvard, whose name is Leslie Dunton-Downer. She’s a mediaevalist

by trade, and a very, very bright and successful woman who happens

to be immensely creative. So she has created a libretto for this

piece, and it’s been a fantastic collaboration, and very intense.

We’ve made a lot of revisions together, which is good. I feel

all of our revisions have made the piece better. We work very well

together, and I find it very nice to work with a woman. We seem

to be able to communicate, and find time where we can both work.

It’s a good situation. So, that whole side of the project has been

phenomenally interesting. It was commissioned by Mstislav Rostropovich,

and it’ll be premiered in May of 1994 in France

— which is very soon in the opera world. It’s

thrilling because I made it for him, and he’s given me so much time. Thomas: Right, really blow it up.

The libretto, and the story, and the music could sustain that.

So, before I write another opera, what I’m going to do is make a

big version of this one. But first I need to get the piece done and

have a video tape of it, and see how that goes, and where the revisions

may lie. Any work like that is so big, and involves so much collaboration.

The set designer might make something which requires a set change,

which suddenly requires music that I didn’t intend, and may not want for

various specific reasons because my music is very tightly threaded throughout

the opera. These things come up, and one has to compromise and

collaborate. I’m not sure, exactly, even until May, what the product

will be.

Thomas: Right, really blow it up.

The libretto, and the story, and the music could sustain that.

So, before I write another opera, what I’m going to do is make a

big version of this one. But first I need to get the piece done and

have a video tape of it, and see how that goes, and where the revisions

may lie. Any work like that is so big, and involves so much collaboration.

The set designer might make something which requires a set change,

which suddenly requires music that I didn’t intend, and may not want for

various specific reasons because my music is very tightly threaded throughout

the opera. These things come up, and one has to compromise and

collaborate. I’m not sure, exactly, even until May, what the product

will be. Thomas: We are, as mass-culture.

We’re getting over some of our hang-ups. One sees a lot of issues

repeating themselves — equal rights,

gay rights, women’s rights — and a

lot of these things are dealing with the same kind of issues. I

hope we, as a culture, will be able to accept each other as human beings,

and love each other, rather than criticize each other for our sexual preference,

or because someone’s a woman, or whatever it may be.

Thomas: We are, as mass-culture.

We’re getting over some of our hang-ups. One sees a lot of issues

repeating themselves — equal rights,

gay rights, women’s rights — and a

lot of these things are dealing with the same kind of issues. I

hope we, as a culture, will be able to accept each other as human beings,

and love each other, rather than criticize each other for our sexual preference,

or because someone’s a woman, or whatever it may be.