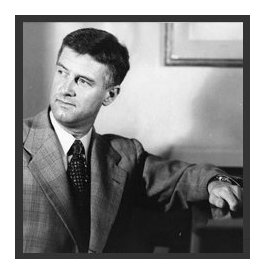

| Ray Burns Green (Sept. 13, 1908-April

16, 1997) was an American composer and music publisher who was born in 1908

(some sources give 1901, others 1909) at Cavendish, MO, near Avalon, and was

raised in San Francisco, CA. The bulk of his basic musical training came in

the city of the Golden Gate, where he studied under such personages as Ernest

Bloch, Albert Elkus and Giulio Silva. In the mid 1930s, he won the George

Ladd Prix de Paris, a two year composition fellowship from the University

of California, Berkeley, to study modern music abroad. While in France, he

studied composition under Darius Milhaud and gained conducting experience

with Pierre Monteux. Instead of remaining in Paris as originally intended,

he explored the continent but was disappointed with the state of music composition

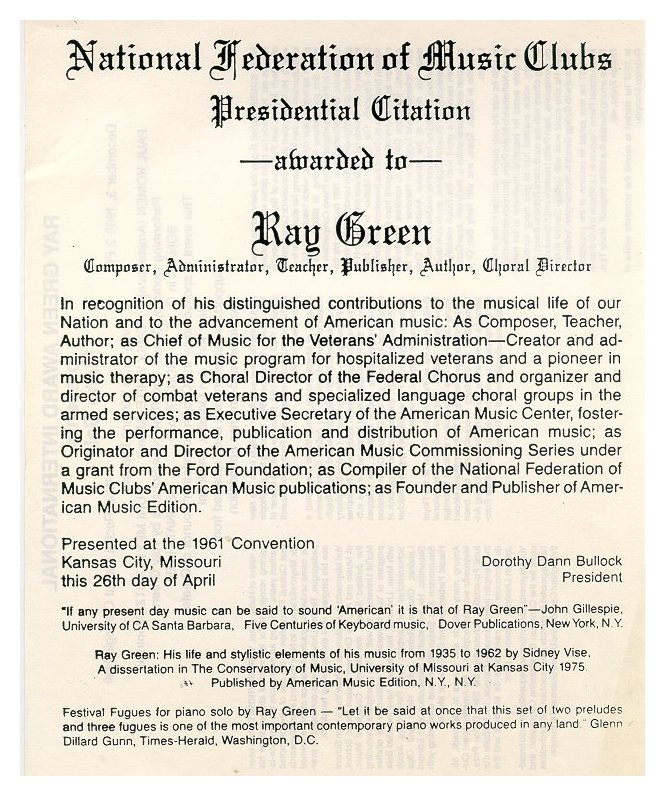

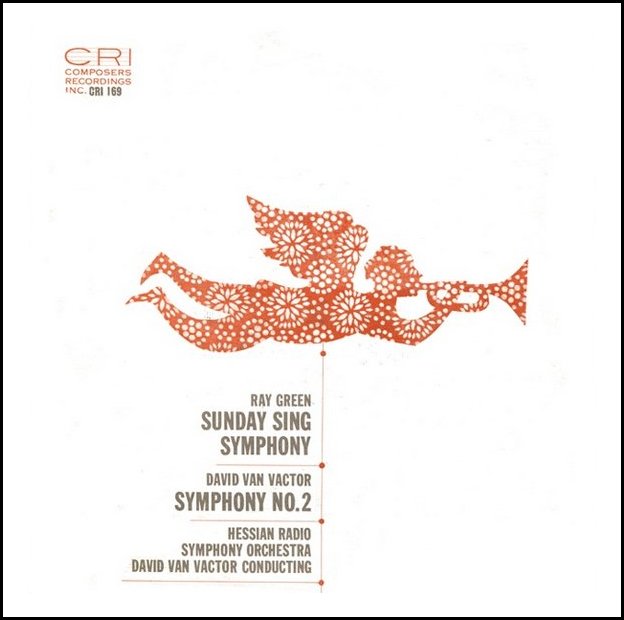

and returned to the United States to discover his own way. After his return in 1937, Green met May O’Donnell, an American modern dancer and choreographer, and wrote the score for her first work, “Of Pioneer Women”. This was the beginning of his career as a composer in the dance field. In 1938 at the Bennington School of Dance he wrote “American Document” for Martha Graham. 1938 also marked the year he married May O’Donnell and began their long and successful collaboration of music and dance. During the years prior to and during World War II he was composer-conductor, first with the Federal Music Project in northern California and then as a member of the Armed Forces. During this time, one of his main interests was in getting music accepted as an essential component to medical therapy treatment in the Veterans Administration hospitals. He was Chief of Music for the Veterans Administration, and in 1948 was invited to become Executive Secretary of the American Music Center in New York City, a position he held for over twelve years. In 1951 Green founded his own publishing company, the American Music Edition (AME), which played an important role in documenting and disseminating new American music by Green, Carl Ruggles, Halsey Stevens, and many other composers. Consisting of manuscripts, business papers, and correspondence, the archive reflects AME’s repertoire as well as the interactions Green had with many key figures in twentieth-century music, including John Cage, Henry Cowell, Charles Ives, Gunther Schuller, William Grant Still, and Virgil Thomson. Perhaps Green’s most striking achievement during his years with the American Music Center was the development, in collaboration with the Ford Foundation of a commissioning series, which during 1957-63 resulted in multiple performances of newly composed American works by a half-dozen participating orchestras. In 1987 he set up the Ray Green Award which was the first piano prize where the teacher and the student share equally in the prize. Green’s influence was felt in the worlds of American music composition, music therapy, modern dance, and music publishing. He tried to create a new American music consisting of a harmonic system removed from the European tradition. This was signified by elements of American jazz, American folk music, Asian music, microtonality, music for dance and electronic music. It was never to be highbrow or too cerebral, but accessible to all audiences. Ray and May lived and worked together for over fifty years and became one of the most formidable combinations of composer and choreographer of their time, producing over forty collaborative works. He died at New York City, NY, in 1997. As composer, the titles of many of Green’s works bespeak his preoccupation with American dialect in terms of music, whether through evocation of hymn tune, country dance, or folk legend. One of his best-known works is Three Inventories of Casey Jones, which consists of two tiny movements that are really conventional piano solos, merely decorated by percussion, which frame a more substantial concerted movement. He completed his Sunday Sing Symphony in 1946. It does not attempt to capture or recreate the atmosphere of a “Sunday Sing,” nor is the work programmatic or descriptive but is based rather on the idea than on the substance of the “Sunday Sing.” Other such works by Green include Jig Theme and Six Changes, Country Dance Symphony, Four Short Songs to texts by Carl Sandburg, Sea charm and I Loved My Friend to texts by Langston Hughes, and Three Choral Songs to texts by Emily Dickinson. He also composed a non-subtitled Violin Concerto as well as Concerto Brevis for Violin and Orchestra. Sidney R. Vise wrote “Ray Green: His Life and Stylistic Elements of His Music from 1935 to 1962” for American Music Edition, 1975. -- From the Walkerhomeschoolblog

-- Names which are links (in this box and in the text below) refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

RG: Well yes, but the thing is that, sure, oh,

I believe that. For example, I heard a performance of the Sonata in D with Tallis Barker playing

it. He is just a young kid — eighteen years old

when he did it — and he did the whole thing by himself.

His teacher, Seymour Bernstein, told me that Tallis worked out the whole piece

himself. Tallis was not a very ‘talkity’ young

person, but he did say that at one point that fortunately he played enough

jazz that he knew what to do in the piece. That was a clue for me that

he knew how to accent passages and bring out the rhythmic fabric was there.

But if you look at the page, it looks like it’s pretty much cut and dried.

But it isn’t at all when you play it, and especially at the tempo it is marked.

It’s intended to go at a pretty good pulse, and he worked this out all by

himself. In the more dramatic section — the

middle section, the intermezzo — he used dramatic

pauses. Maybe some other composer might object strenuously, but I didn’t.

I found them very affective because he built up such a momentum before the

dramatic pause. It’s an overlong pause — a Luftpause — that

actually embellished the emotional effect of the sound itself. In a

case like that, I would applaud his use of it. I mentioned this to

the young girl who is playing the piece in December. She had done it

last May in London, where she got very good reviews on the piece.

I told her that some of those dramatic pauses that Tallis used I found very

effective. I didn’t say she must put them in, I just said it as a suggestion.

That is frequently the best way, instead of confronting somebody saying he

or she left that out. That’s a pretty bland, blunt statement, and

you don’t get very far with the performer.

RG: Well yes, but the thing is that, sure, oh,

I believe that. For example, I heard a performance of the Sonata in D with Tallis Barker playing

it. He is just a young kid — eighteen years old

when he did it — and he did the whole thing by himself.

His teacher, Seymour Bernstein, told me that Tallis worked out the whole piece

himself. Tallis was not a very ‘talkity’ young

person, but he did say that at one point that fortunately he played enough

jazz that he knew what to do in the piece. That was a clue for me that

he knew how to accent passages and bring out the rhythmic fabric was there.

But if you look at the page, it looks like it’s pretty much cut and dried.

But it isn’t at all when you play it, and especially at the tempo it is marked.

It’s intended to go at a pretty good pulse, and he worked this out all by

himself. In the more dramatic section — the

middle section, the intermezzo — he used dramatic

pauses. Maybe some other composer might object strenuously, but I didn’t.

I found them very affective because he built up such a momentum before the

dramatic pause. It’s an overlong pause — a Luftpause — that

actually embellished the emotional effect of the sound itself. In a

case like that, I would applaud his use of it. I mentioned this to

the young girl who is playing the piece in December. She had done it

last May in London, where she got very good reviews on the piece.

I told her that some of those dramatic pauses that Tallis used I found very

effective. I didn’t say she must put them in, I just said it as a suggestion.

That is frequently the best way, instead of confronting somebody saying he

or she left that out. That’s a pretty bland, blunt statement, and

you don’t get very far with the performer. BD: You had a close relationship with Carl Ruggles.

Tell me a bit about him!

BD: You had a close relationship with Carl Ruggles.

Tell me a bit about him!

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on September 30, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.