| Melinda Wagner (born February 25,

1957 in Philadelphia) is a winner of the 1999 Pulitzer Prize in music. Her

undergraduate degree is from Hamilton College. She received her graduate

degrees from University of Chicago and University of Pennsylvania. She also

served as Composer-in-Residence at the University of Texas (Austin) and at

the ‘Bravo!’ Vail Valley Music Festival. Some of her teachers included Richard Wernick, George Crumb, Shulamit

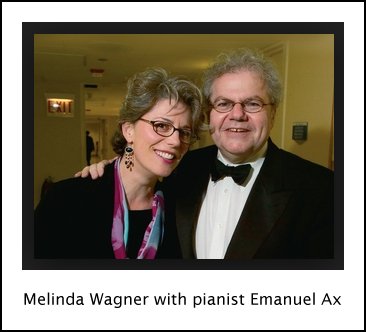

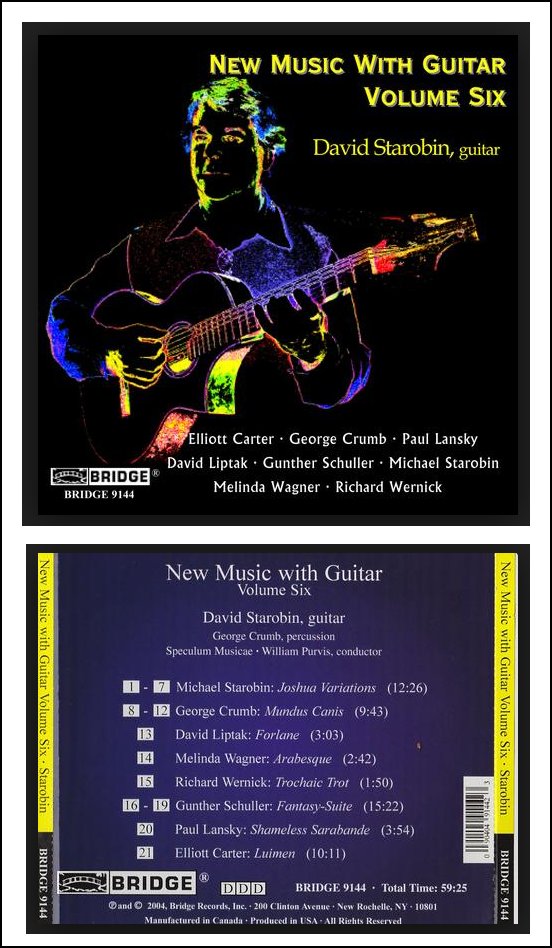

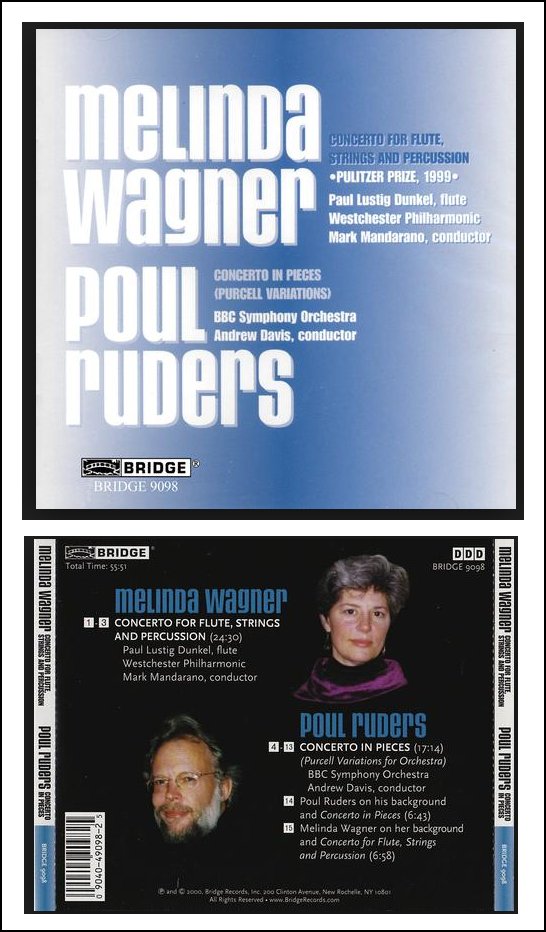

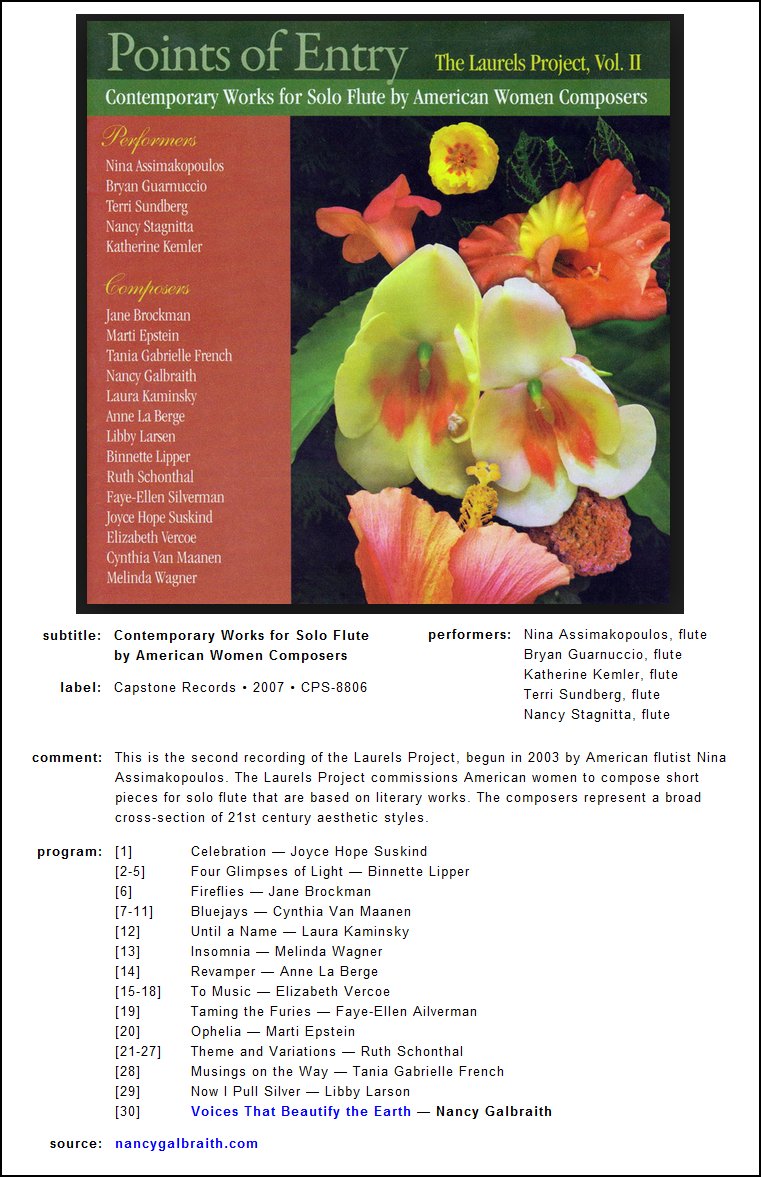

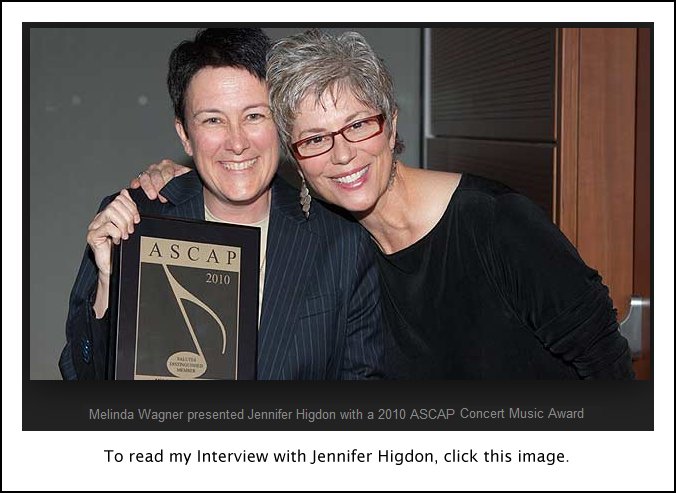

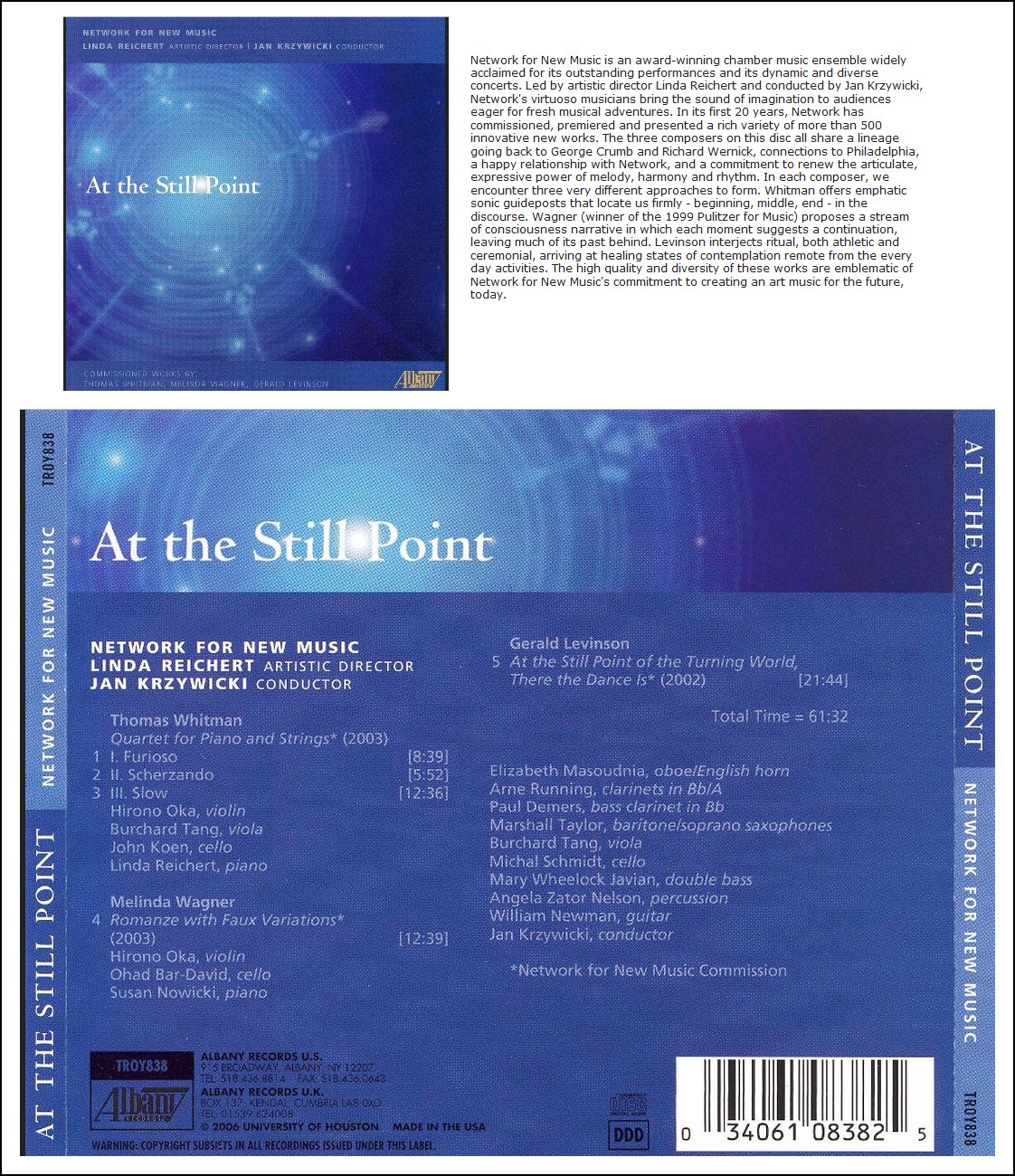

Ran, and Jay Reise. A resident of Ridgewood, New Jersey, Wagner won the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for her Concerto for Flute, Strings and Percussion. The Chicago Symphony has commissioned three major works - Falling Angels (1992); a piano concerto, Extremity of Sky (2002) for Emanuel Ax; and a forthcoming work. Extremity of Sky has also been performed by Emanuel Ax with the National Symphony, the Toronto Symphony, the Kansas City Symphony, and the Staatskapelle Berlin. Other works have been performed by a number of orchestras, including the New York New Music Ensemble, the Network for New Music, Orchestra 2001, the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, and many other leading organizations. Wagner was also commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for a concerto for principal trombonist Joseph Alessi, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Barlow, Fromm, and Koussevitzky Foundations, the American Brass Quintet, and from guitarist David Starobin. She has received a Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an honorary degree from Hamilton College, as well as a Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Pennsylvania. Her other performances include the Dallas Symphony, the American Composers Orchestra, the Women's Philharmonic, the New York Pops, and the US Marine Band. Wagner has taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Swarthmore College, Syracuse University, and Hunter College. She has lectured at many schools such as Yale, Cornell, Juilliard, and Mannes. She resides in New Jersey with her husband, percussionist James Saporito, and their children. -- Throughout this page, names

which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

On her first visit, in February of 1993, I had the chance to speak with her

a few hours before the first concert of the series. Then, just over

ten years later, in May of 2003, we met again for our second conversation.

Both of those encounters are presented on this webpage. She was also

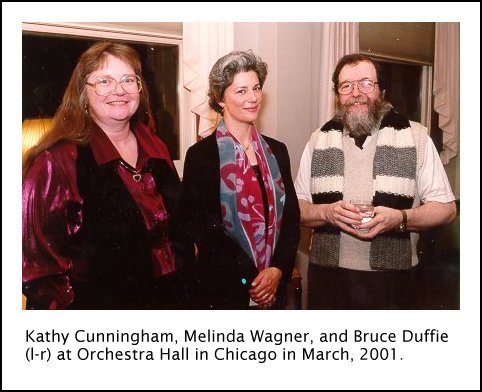

in Chicago in March of 2001, and though we did not have a formal interview

at that time, we did see each other again at a private reception, and that

gathering is documented in the photo at right.

On her first visit, in February of 1993, I had the chance to speak with her

a few hours before the first concert of the series. Then, just over

ten years later, in May of 2003, we met again for our second conversation.

Both of those encounters are presented on this webpage. She was also

in Chicago in March of 2001, and though we did not have a formal interview

at that time, we did see each other again at a private reception, and that

gathering is documented in the photo at right.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean to say

that music, as we know it, is intelligent???

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You mean to say

that music, as we know it, is intelligent??? MW: It really hasn’t changed me at all, I have to

say. I feel the same person I was. I feel like I have the same

foibles that I’m forever working on trying to get rid of. Maybe there

are new foibles and I’ve gotten rid of the old ones, but there are always

weaknesses in my work.

MW: It really hasn’t changed me at all, I have to

say. I feel the same person I was. I feel like I have the same

foibles that I’m forever working on trying to get rid of. Maybe there

are new foibles and I’ve gotten rid of the old ones, but there are always

weaknesses in my work. BD: That seems very odd. Usually we have stories

about the ink still being wet on the page!

BD: That seems very odd. Usually we have stories

about the ink still being wet on the page! MW: That’s really the core of composer’s work,

to make sure that the parts of the piece link up in a most honest way.

For instance, it’s awfully easy to write very loud and dramatic music, but

I would feel dishonest if I hadn’t done a lot of preparation compositionally

for a big climax in a piece. It’s easy to ‘wow’ listeners by using

a lot of cymbals and timpani and a lot of brass, but you have to make that

inevitable compositionally.

MW: That’s really the core of composer’s work,

to make sure that the parts of the piece link up in a most honest way.

For instance, it’s awfully easy to write very loud and dramatic music, but

I would feel dishonest if I hadn’t done a lot of preparation compositionally

for a big climax in a piece. It’s easy to ‘wow’ listeners by using

a lot of cymbals and timpani and a lot of brass, but you have to make that

inevitable compositionally.

MW: No, I don’t anymore but, at that particular

time in my life, that was very nice. Perhaps that is what’s needed

right now. I live with two drummers who play in the basement, and it

comes up through the heating system. I’ve gotten used to composing

while I’m hearing Gene Krupa downstairs, so it’s pretty interesting in my

house. [Laughs]

MW: No, I don’t anymore but, at that particular

time in my life, that was very nice. Perhaps that is what’s needed

right now. I live with two drummers who play in the basement, and it

comes up through the heating system. I’ve gotten used to composing

while I’m hearing Gene Krupa downstairs, so it’s pretty interesting in my

house. [Laughs]

© 1993 & 2003 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on February 4, 1993, and May 21, 2003. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995, 1997, and 1998, and on WNUR in 2003 and 2005. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.