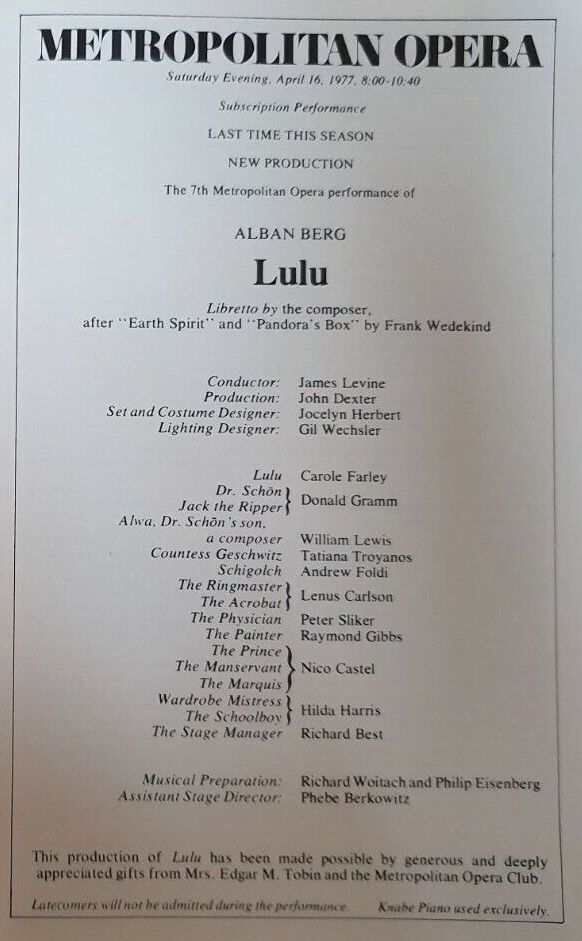

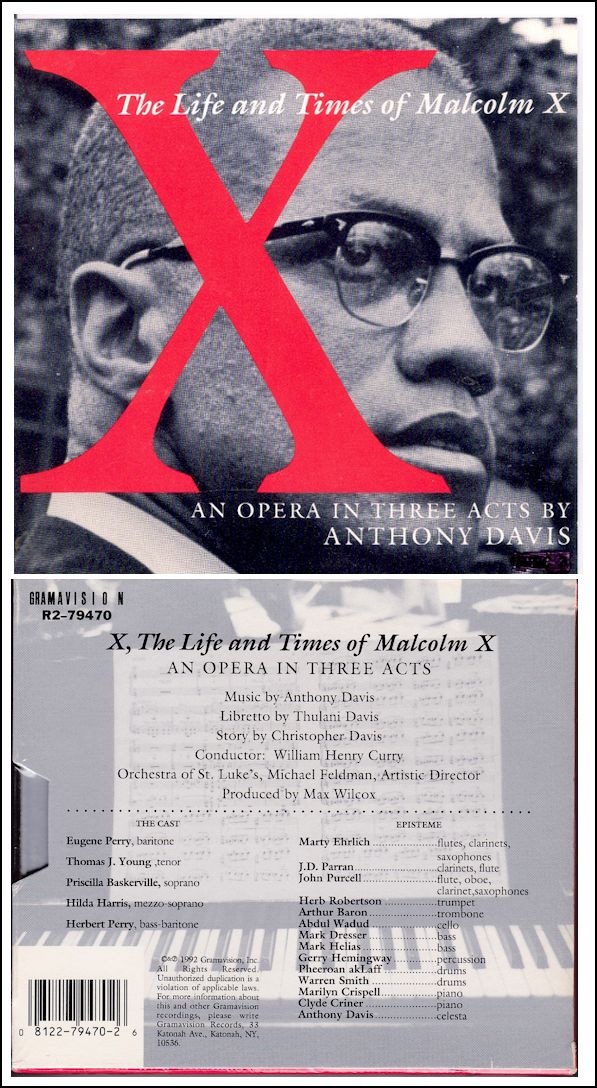

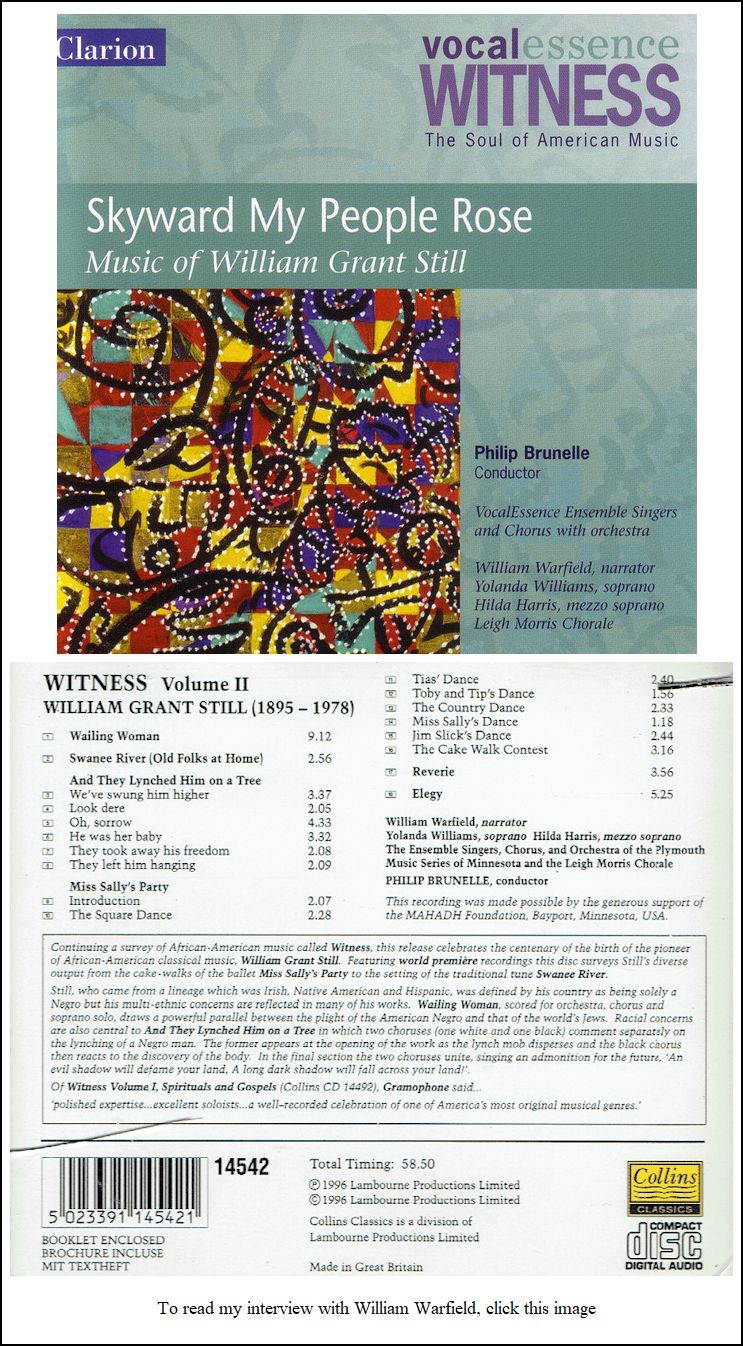

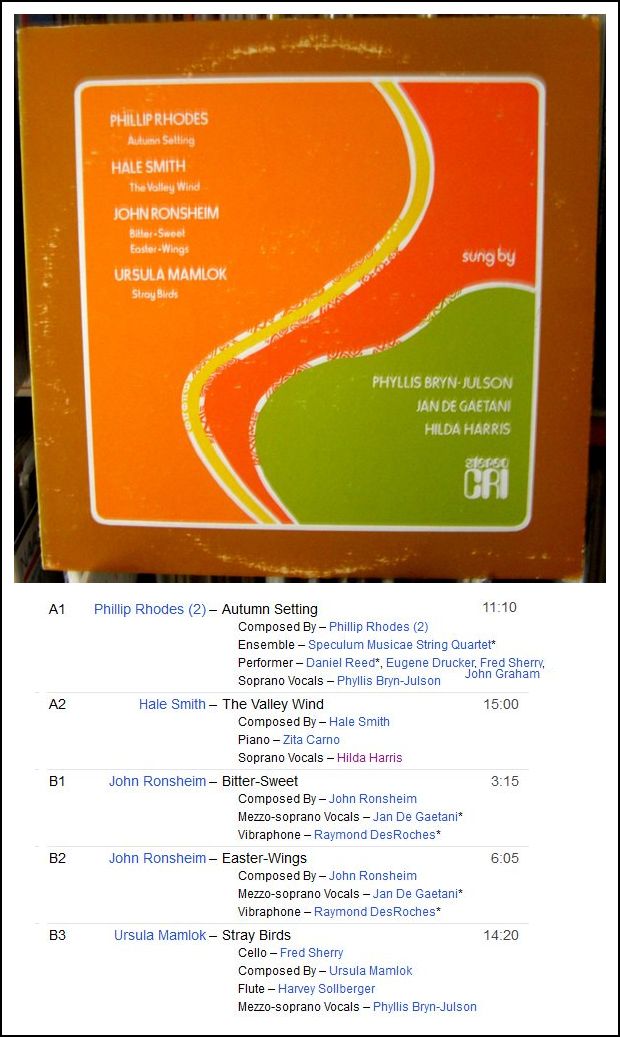

Mezzo-soprano Hilda Harris, formerly a leading artist of the Metropolitan Opera, has performed throughout the United States and Europe. A native of Warrenton, North Carolina, she is known for her portrayals of the "trouser" roles in the mezzo repertoire. She has established herself as a singing actress and has earned critical acclaim in opera, on the concert stage, and in recital. At the Metropolitan Opera, she made her debut as the Student in Lulu and also sang Cherubino (Le nozze di Figaro), the Child (L'Enfant et les sortilèges), Siebel (Faust), Stephano (Roméo et Juliette), Hansel (Hansel and Gretel), and Sesto (Giulio Cesare). During her extensive career, she has sung such roles as Carmen in St. Gallen, Switzerland [photo at right], Brussels, and Budapest. In Holland and Belgium she sang the roles of Dorabella (Così fan tutte) and Rosina (Barber of Seville), and the title role in La Cenerentola. She has also sung leading roles with the San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, New York City Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Seattle Opera, Spoleto USA, and the Spoleto Festival of Two Worlds in Italy. She has appeared extensively in symphonic and oratorio repertoire with the New York Philharmonic, Pittsburgh Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Oregon Symphony, Quebec Symphony, Helsinki Orchestra, Sweden's Malmö, Symphony and the radio orchestras of Hilversum in the Netherlands. Ms. Harris is a member of the Chicago-based Black Music Research Ensemble, whose purpose it is to discover, preserve, promote and perform music of black composers. Her accomplishments have been documented in And So I Sing, by Rosalyn M. Story; Black Women in America, an Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Darlene Clark Hines; The Music of Black Americans by Eileen Southern; and African-American Singers by Patricia Turner. Ms. Harris's discography includes Hilda Harris (a solo album); The Valley Wind (songs of Hale Smith); Art Songs by Black American Composers (album); X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X (CD); From the South Land, songs and Spirituals by Harry T. Burleigh (CD); and Witness, Volume II, compositions by William Grant Still (CD). Ms. Harris taught voice at Howard University from 1991 through 1994 and is presently a member of the voice faculties of Sarah Lawrence College and Manhattan School of Music. She maintains a private studio in New York City and is on the voice faculty at the Chautauqua Institution during the summer months. == Biography from the African American Art

Song Alliance

|

© 1984 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 1, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.