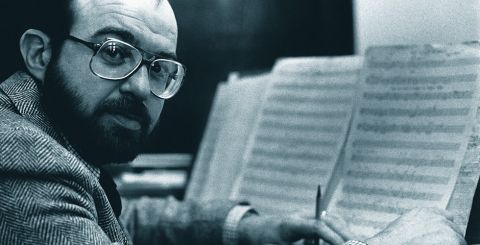

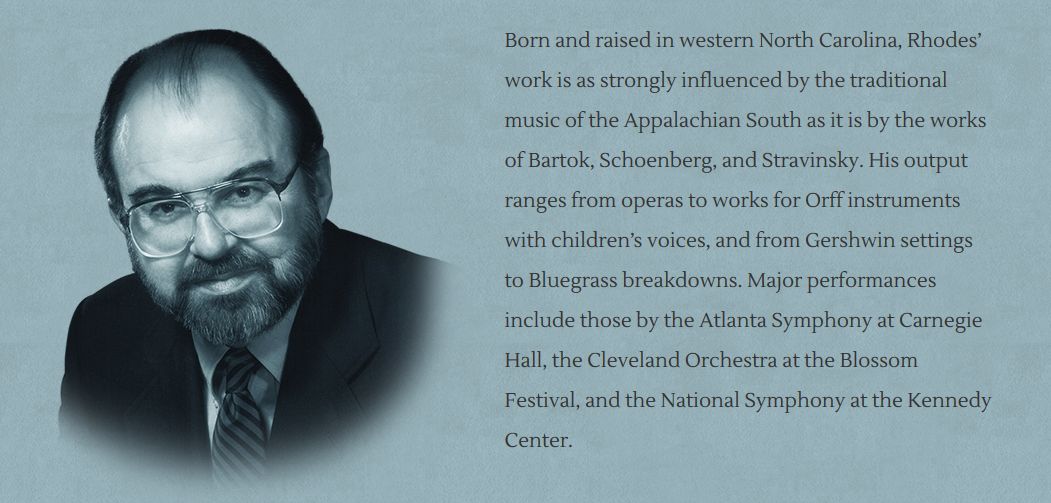

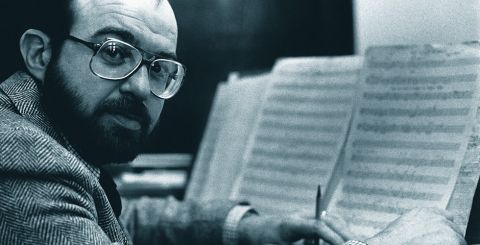

Composer Phillip Rhodes

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Phillip Rhodes is Composer-in-Residence and Andrew W. Mellon Professor

of the Humanities Emeritus at Carleton College where he joined the faculty

in 1974. Born in western North Carolina in 1940, he received degrees

from Duke University and the Yale University School of Music. He has

been the recipient of numerous commissions and composition awards, including

grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment

for the Humanities, the Rockefeller Fund for Music, a citation and award

from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a

McKnight Fellowship, two Fromm

Foundation Commissions, and a Bush Foundation Fellowship for Artists. [Names

on this webpage which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

Rhodes came through Chicago at the very end of August of 1994,

so I knew immediately that he would get a full program about nine months

later to mark his fifty-fifth birthday . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: You say you don’t imagine yourself

being fifty-five. Why not?

Phillip Rhodes: I don’t know. You sort of

think of yourself getting older, and I’m sure everybody thinks that and

says that. Sometimes when you’re working outdoors or trying to play

golf, you do realize you’re older than you think you are.

BD: Does your music get older at all?

BD: Does your music get older at all?

PR: I really not sure what you mean by that.

BD: Let me break it into a couple of parts

then. Is the technique of composing easier because you have so much

experience?

PR: I think that’s probably true. You

know what you’re looking for, and pretty much how to do it. Of course

you’re always trying something that you’ve never tried before, or doing

it in a way you’ve never tried before. So, yes, you do have some

reliable things that you know how to do, and you can count on those things

working. But even so, you’re still trying to experiment with finding

new things.

BD: Then does the musical content of your

work continue to grow year by year?

PR: I would like to think so. I’m not

sure what people who know anything about my music would say. My

research field is traditional Appalachian music, and I teach courses in

that as well. I go to festivals, and all kinds of things that have

to do with the culture, so I’m always learning new things about the culture

that I then internalize, and it shows up in my music.

BD: Does that make your music more American

or just a different kind of American?

PR: Lord knows what American music is, but

it certainly relates to a culture that is long-standing in the sense

of when we begin to settle this country.

BD: Does it go back farther than that, to

the roots of the people who came over?

PR: No, mostly it’s Scotch-Irish, so it goes

back to the migrations from Northern Ireland shortly after the turn of

the Eighteenth Century.

BD: Is that your heritage also?

PR: It is.

BD: Do you go back to the old country periodically?

PR: I’ve been to Scotland doing research on

a particular kind of hymn-singing that one finds among the Baptist sects

in Eastern Kentucky, but I have not been to Northern Ireland.

BD: Do you find a direct link between that

music and the Appalachian music, and then your music?

PR: Certainly between the first two.

Again, in this particular style of hymn-singing the strength of the link

is very obvious and very direct. In my work though, it somehow exhibits

itself when it comes in one way, and then turns around and comes out in

a not-so-direct way. But I think it’s related.

BD: Do you purposely try to accentuate all

of this, or does it just become part of the fabric?

PR: Sometimes you do try to accentuate it if

you’re working with a given tune, for example. Otherwise, as you

say, it exhibits itself in the fabric of how you think about something,

or if you have a particular rhythmic feature which may not be obvious,

but certainly is a part of my thinking of how the piece is put together.

BD: Coming back to my original question, does

this continue to grow and grow, or do you find you have gotten a specific

way of working with it which you keep using?

PR: Both! I hope it continues to grow

as I learn more and better things. But I do know how certain things

work, and how to use them, and what’s going to happen when I do use them.

So in that sense I do return to certain aspects of pieces, or remember

how things are put together.

BD: You write music for the concert hall, as

well as church music and instructional music?

PR: I certainly do church music, and have

done instructional music.

BD: How do you reconcile the folk idiom of

the Scotch-Irish and the Appalachian into the concert music?

PR: [Laughs] I don’t see why I have to reconcile

it at all.

PR: [Laughs] I don’t see why I have to reconcile

it at all.

BD: So music is music is music is music?

PR: Pretty much!

BD: Is the concert music that you write for

everyone?

PR: I should like to think it is.

BD: Are you aware of the audience when you

are writing the music?

PR: In some cases, yes. It depends on

what kind of particular commission one is working one. You’re certainly

aware of the performers. I did a commission for the American Orff-Schulwerk

Association, and that came about because my children were growing up

and were being taught by Orff teachers. I find the system very

attractive as a means to teach students. So certainly, I was aware

of the kinds of student musicians who’d be playing this piece, and in

this case, the audience is always their parents. So, you are aware

of who that particular the audience is, but other kinds of things you

are aware who the players are, and that’s part of the fun of it. To

me, commissions for certain groups or certain kinds of people

— including great players — are lots

of fun to do. A group like Speculum Musicae, for example, is known

the world over for being able to play anything and everything. You

think of it, and they can play it. That particular kind of challenge

is very different from writing for school children, for example.

BD: Do you particularly try something that’s

uniquely difficult for the Speculum group, just to see if they can get

around it?

PR: No, I wouldn’t say that at all.

It’s just fun to realize that they can do practically anything.

A lot of really fine players like challenges.

BD: Is it more challenging to write something

for children, and yet make it interesting to you and to the audience?

PR: That’s a really hard one, and you said it

exactly right. To be able to satisfy what you, yourself want to

write, and that children can play is a really tough one, and it’s not

easy to do. But I have enjoyed working with those kinds of things,

and we need to do that as composers.

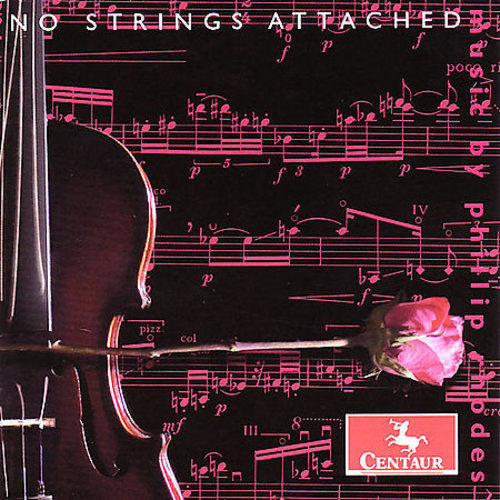

BD: You’ve had quite a number of

recordings. Are you pleased with the recordings that have been

made of your music?

PR: Yes, without exception.

* * *

* *

BD: You’ve worked as a teacher for a long time.

Any regret about that?

PR: Oh, no. I like teaching.

BD: This is college-level at the moment?

PR: Yes.

BD: Are your students going to be composers,

going to be musicians, or just going to be real people?

PR: Some of all of that. One of the courses

that really interests me is ‘Introduction to Music for General Students’

because it’s very often those people who will, in their lifetimes, sit

on boards of symphony orchestras and ballet companies, and school boards

where public school music is debated pro and con. I get a great deal

of pleasure out of having some input to those kinds of people because it

does matter.

BD: What kinds of influence do you want to have on those

young minds?

BD: What kinds of influence do you want to have on those

young minds?

PR: That they understand why people write music;

why does this sound this way; why does Bach sound different from Stravinsky;

how does it affect you when you hear it; what do you think this person

was trying to impart in writing a piece of music; and that it matters.

BD: That’s one of the most important things

— that it matters.

PR: Right. Beethoven is talking to you

about something that matters as far as our collective human condition

goes. They need to know that, and they need to know why it matters

for the future.

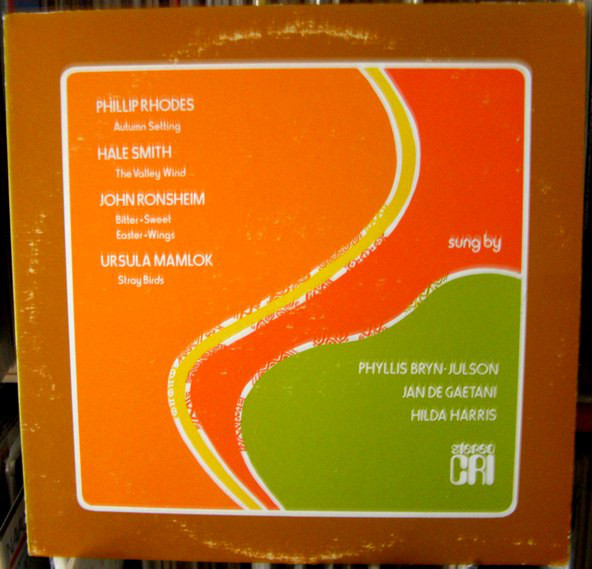

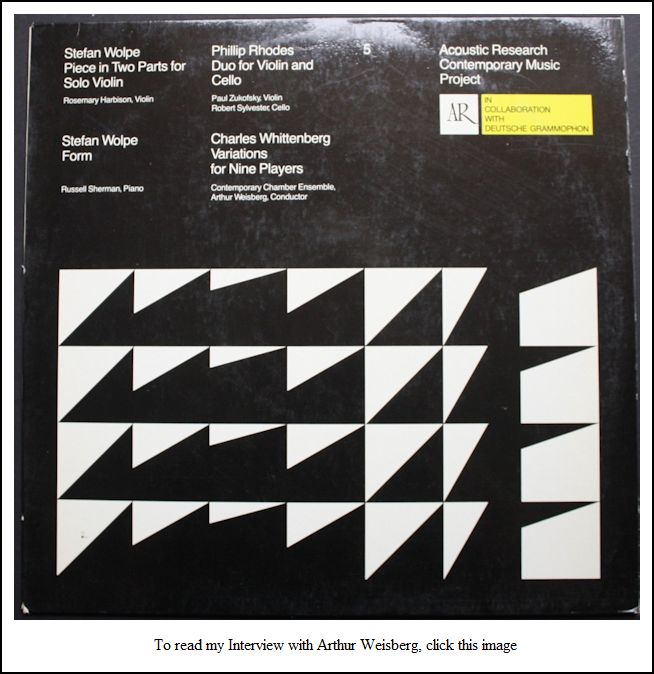

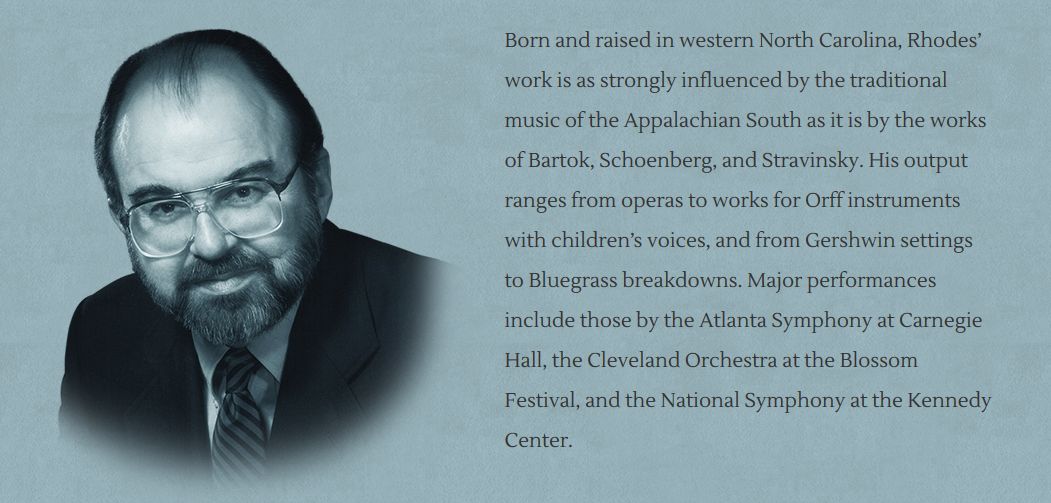

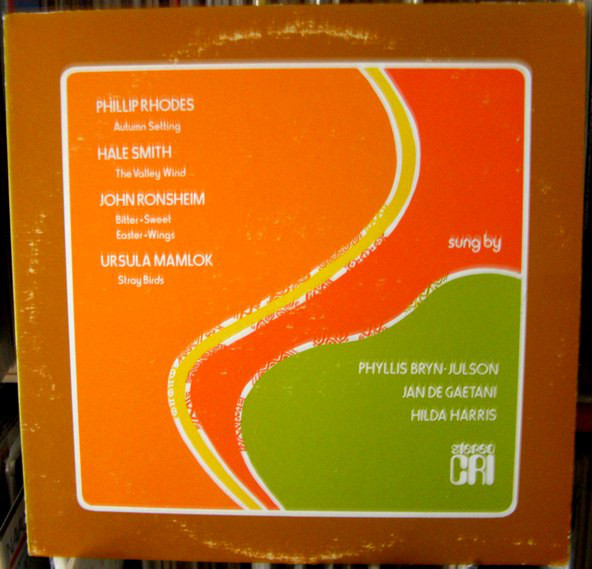

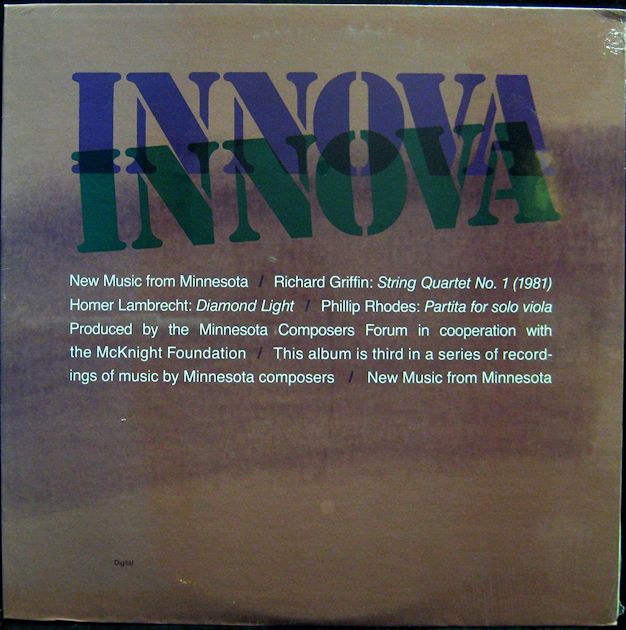

BD: Is Phillip Rhodes talking to you about

something that matters in his music? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interivews with Hale Smith, Ursula Mamlok, Phyllis Bryn-Julson,

and Hilda Harris.]

PR: I certainly hope so.

BD: Is it a specific thing, or is it a general

thing?

PR: Again, it might be specific in one instance

and very general in another. These things are sometimes difficult

to talk about, but mostly it’s a commonly shared feeling or perception

about how one’s life is in relation to other people.

BD: I realize that I’m asking the tough riddles

that you are used to putting into music rather than into words.

PR: Yes, you ask these questions, and then

I’m supposed to respond to them in words, and I don’t put them in words

to myself. So it’s very difficult to do that because I simply don’t

sit and ponder these things. When you’re asked to comment in a radio

interview about such things, it’s not easy.

BD: I understand. Is it safe to assume,

though, that the music has pondered these things for you?

PR: I hope so. I like to think so.

BD: Well, let me hit the big question from

a little different angle. What’s the purpose of music?

PR: [Thinks a moment as he moves his head and

rolls his eyes] Why do you have to ask me that? [Both laugh]

I don’t know! I find many purposes in music. I’m quoting

somebody, I can’t remember who, that the purpose of music is to make

one sing and dance and laugh and cry. It’s all of these kinds of

things. Church music moves one in a certain kind of way. The

opening of the Beethoven Fifth is another thing. What is

this, and why is he so intent on beating me over the head with this idea?

It asks questions that are difficult to answer, but that have to

be addressed in some many. So, that’s certainly one of the purposes

of music. In broad history, music has also been a call to national

arms. There are all kinds of purposes of music, and I pretty much

enjoy them all. I like dancing music. I like singing music.

I like the human voice. It’s one of my very favorite means

of communication.

BD: [Pouncing on this particular item] Tell

me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human voice.

PR: The joys are hearing it sung as you imagined

it originally, in all this glorious high register without fault or strain.

There really aren’t that many sorrows in writing for the human voice.

I grew up in church choirs, and when one tries to write for church

choir, you have to be aware of what limitations are. There is but one

hour, a Wednesday evening rehearsal, that can bring to the situation!

[Laughs] But one of my favorite singers was, and is, Phyllis Bryn-Julson.

BD: She’s made a number of recordings of your

music.

PR: Yes, and Boulez, and Schoenberg,

and everything you can think of. She is probably the leading soprano

of contemporary music of her generation. She and I have known each

other for a long, long time — since our student

days at Tanglewood — and it was a particular joy

to write for a singer like her. But for me, one of the most subjective

things of all about singing is whether or not one simply likes the sound

of the voice. Her voice was so beautiful, and she could do anything

with it. That was one of the particular joys of writing for the

voice.

BD: When you write, you obviously have her

in mind. Does that preclude other sopranos from doing it, or must

they simply rise to her level?

PR: No, I wouldn’t say that. There are

many sopranos — many more than one would think

— that can sing contemporary music, and sing it perfectly

and beautifully, and for whom I would be very happy to write.

BD: Would it be completely different when

you’re writing for one soprano as opposed to another soprano?

PR: Not completely different. There might be different

aspects of things she might focus on — the range,

for example, or kind of thing.

PR: Not completely different. There might be different

aspects of things she might focus on — the range,

for example, or kind of thing.

BD: With vocal music, you have the unique

problem of texts. How do you decide what text you’re going to

use?

PR: Sometimes you’re given texts, and that’s

that. I should think that most composers who write vocal music

with text spend a lot of time reading things such as poetry. I

do that, too, probably not as much as I should. I had a very interesting

conversation with Dominic

Argento. He reads an enormous amount of stuff and writes an

enormous amount of vocal music. Usually, if I’m writing a vocal

piece, then I start reading and start looking for something specific,

but I usually have some kind of thematic thing in mind. There is

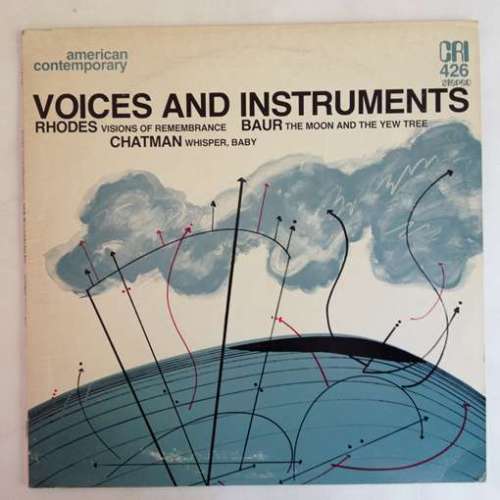

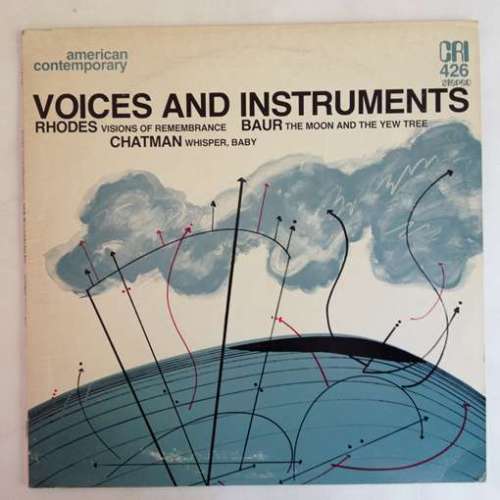

a piece we were talking about, called Visions of Remembrance, for

two sopranos. The texts are collected around a theme of how we remember

things from our childhood. So, we talked about how one would go about

setting that to music so as to evoke those kinds of hazy childhood memories.

BD: Once you had it all down on paper, did

it work?

PR: I think it worked. It seems

to work.

BD: Are you ever surprised by what you hear

once the performers get a hold of the music and start playing or singing?

PR: [Laughs] If you’re surprised too often,

something’s wrong. But one in a while, yes, you do get surprised

— not by what it sounds like, necessarily, but what somebody

else does to it, or projects it in a way that you hadn’t thought of. Very

often you’re thinking of detailed ideas about putting all these notes

together in this register, in this range. You know what it’s going

to sound like on the clarinet, and you hear the soprano sing that word

on this note. Then, in working out the detail — in

which I take great delight — you sometimes forget

what a singer or a violinist can or cannot actually bring to it from their

own background. This is this enormous lineage of how we make music,

and once in a while you get really delightful surprises that the performer

himself or herself brings to the thing.

BD: But at some point, if they’re pulling

and pushing your music, is it no longer really your music?

PR: You mean if they go beyond the limits

of what you’ve written down? Yes, but that’s true of anybody’s

music.

BD: I’m asking where those limits are for

you.

PR: I’m pretty forgiving with where those limits

are, but some things have to be done in a certain way. I’m very specific

in the notation about how they’re supposed to be done, or at what speed,

or what dynamic. Sometimes performers can argue you into an agreement

about something. “Let’s try this and see

what it sounds like,” and that’s fine. But

at some point, if it goes beyond the limits of what you think it should

be, you have to say, “No, I don’t think we’ll do

it that way. Let’s do it the way I wrote it in the first place.”

BD: So you’re willing to be convinced, but

you have to really be convinced?

PR: I’m certainly willing to hear what a performer

has to say about how they want to do something, particularly if it involves

a matter of breath. That’s always tricky business. I grew

up as a clarinet player, and you always have to be aware with wind players

and singers. You have to breathe somewhere, so you try to take that

into account. So, if there’s a problem like this, certainly you

listen to them.

BD: Do you litter your scores with directions,

or do you leave them pretty clean?

PR: One difference at my age now from what I did

when I was younger is my directions are becoming fewer and fewer.

[Laughs] I’m not sure if that’s a good thing or a bad thing, but

you sit and you look at a page, and you write things down, and you finally

come to the point of trusting the musicians. If they have any sense

at all, you’re not going to have to write all this stuff down. They

will simply respond to it the way they’re supposed to. I hope that

works, and generally it does.

* * *

* *

BD: Obviously, you have grown over the years. Do

you feel that the performers’ instincts and abilities

have also grown over the years?

BD: Obviously, you have grown over the years. Do

you feel that the performers’ instincts and abilities

have also grown over the years?

PR: Oh, without question! There is no question

about that! Even in the whole field of contemporary music, certainly,

but there are a couple of examples in my own work that show the players

are getting better and more experienced. The singers are probably

the last ones because their instruments are so hard to control, and to

get to produce a certain note unless they have perfect pitch. But

certainly, the whole area of performance has grown in its ability and its

familiarity with contemporary music. It’s very exciting.

BD: The technical abilities of performers

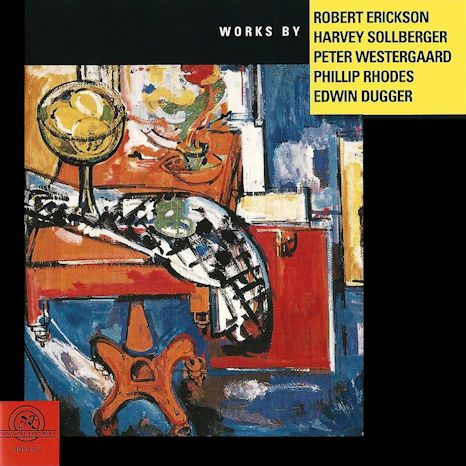

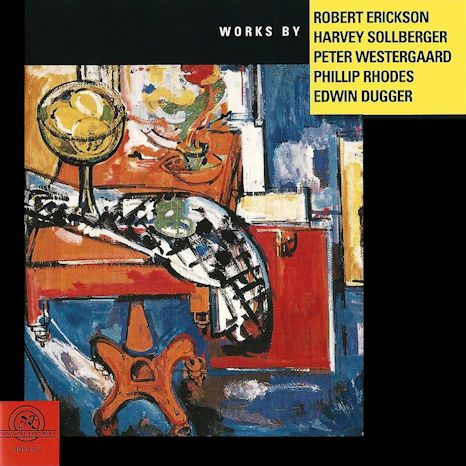

have grown. Has the musical understanding grown? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Robert Erickson, and

Harvey Sollberger.]

PR: Yes, I think it has. Their musical understanding

is taught to them on the basis of the past not the present. For

example, you can go back to the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, or to

any of these pieces that could not be played, and now they are common fare

for auditions of graduate students. Their musical and technical understanding

of those pieces at the level of a good player is really outstanding. We’re

almost out of the Twentieth Century, but there’s enough understanding of

Twentieth Century music under the belt of performers now that they can claim

considerable understanding to contemporary music.

BD: Are you optimistic about the whole future

of where music is going?

PR: These are really questions that lets oneself

ponder. I’m not sure what the outcome would be, but I don’t think

either optimistically or pessimistically about it. I guess if I were

pushed on it, I would not be terribly optimistic. It’s not a matter

of good performers or great composers; it’s a matter of where is our

audience that is interested in keeping music alive. That question’s

been going on for many, many years, and that’s why I’m interested in teaching.

That’s why I’m also interested in the parenting of public school music,

because that’s where a lot of this is grounded, and where it has to come

from. I would not even be in music if it were not for public school

music. I grew up in bands from the fifth grade on, and I had great

teachers.

BD: Where was this?

PR: In North Carolina. I’m proud of

that, and I’m optimistic about the state of the profession because the

professionals are really astounding, and getting better all the time.

I guess if I had to put it crudely, I’m not so optimistic about the market

place.

BD: Let me ask a slightly different question.

Are you optimistic about where contemporary music is going, and the unique

directions that composers are taking?

PR: As far as I can tell. Sometimes I pay

a lot of attention and go to a lot of concerts in different parts of

the country, and it strikes me as pretty much a free-for-all as to what’s

going on.

BD: Is that a good thing, or a bad thing,

or just a thing?

PR: I have no idea whether it’s good or bad.

It just seems to me to be a fact that what’s happening in contemporary

music composition is that there are so many influences from so many directions.

Since I have been composing, there’s always been a jazz influence,

and some of the younger composers show a rock influence which they manage

to incorporate into their work very convincingly. There are other

cultural influences. There are all kinds of things going on.

There’s also the effect of electronic media of all sorts, be it computer-generated

or synthesized. There’s so much information that’s available to use,

or to incorporate, or build on, or to ignore, that it does strike me as

literally a free-for-all.

BD: Is it getting to be like cable television

where there are too many choices?

PR: [Has a huge laugh] Possibly!

I could not make a definitive statement about that. It’s hard to

tell.

BD: You teach and counsel young composers. What

advice do you have for the young composer coming along today?

PR: Most of my teaching with younger composers

is at a technical level, acquiring the necessary skills to be able to do

what you want to do, and say what you have to say. How they choose

to do that, or what language they choose to use, they generally develop

later. Most of the younger composers that I get are basically interested

in some kind of advanced tonal language which shows the influence of all

kinds of Twentieth Century and popular music. So unless I’m asked

the direct question, I do very little counseling about what one should do,

or how one’s music should be. That really is up to the person.

My responsibility as a teacher at the undergraduate level is to develop

skills and insights and analysis into how other music works, and how one

might use that, or adapt that particular kind of technique in one’s own

music.

BD: Is there a point where they balance the technique

and the inspiration?

BD: Is there a point where they balance the technique

and the inspiration?

PR: Sometimes you can say that, yeah.

BD: What about in your own music?

PR: Again, it depends on what kind of piece it

is, and what circumstances you’re working under. What I have always

hoped to do is at least produce a competent piece, and to do that you

have to rely on your skills, and your craft, and your imagination.

I’ve always been very gun-shy trying to describe with any precision what

inspiration is. Inspiration may be a good idea, or something that

wakes you up in the middle of the night — which

does happen — and you have to get up and write

it down, or you have to keep singing it all night and keep yourself awake

so that you won’t lose the idea.

BD: Sing it into a tape recorder and hope

that you can understand it when you wake up!

PR: [Laughs] That’s a better thing to

do.

BD: When you’re writing a piece, and you’re

putting the notes down on the page, are you always in control of where

the pencil goes, or are there times when the pencil controls your hand?

PR: I like to think I’m in control of what’s

going on and where I’m going. Sometimes things happen that still

astound me at the age of fifty-five, and I’m not quite sure how they happen.

It’s probably some kind of sub-conscious working

out of pieces of a puzzle. These things happen because they are

in your grasp, and you know what they are. You just haven’t put

them down in order yet, and sometimes this putting down in order seems

to occur quite by itself. Then you end up in a spot you’d envisioned

months ago, but weren’t quite sure how you were going to get there. These

things happen, and you’re delighted when they do. So, you look up

and say, “Thank you very much,”

and go on.

BD: Before you start writing the piece, are

you aware of how long it will take to perform the piece when it’s finished?

PR: No, not always, but sometimes commissions

can be very specific. They want a piece between 13 and 16 minutes

long, so you respond to that by thinking in such a scale, or in so many

movements, or variations, or whatever that will produce a work of the required

length. This is, of course, if you’re interested in taking that kind

of commission.

BD: I just wondered if you ever get started

on something, and you know it’s either going to be much too short or

much too long, so you leave that for something else and start again?

PR: I guess that happens sometimes.

Sometimes it’s hard to make something longer than it wants to be.

Either you have to be satisfied with that and the context you’re in, or

save that for another piece. At least in myself and in my work,

I’m not aware of not having made things longer than they need to be.

BD: When you’re writing a piece, and you’re

working with it, you’re revising and you’re tinkering. How do you

know when to put the pen down and say it’s done?

PR: I try at some point to devise an end for the

piece. This is how I want the work to end, and this is what I want

it to sound like. In some case these are the notes, and the distribution

of those notes that I want the end to be, especially on a piece that

has a text. You pretty much know where the end is, and then you go

about creating the aura that you want for it. So, you set that out,

and then you start working on the rest of the piece. That’s what I

was talking about a minute ago. Sometimes, in working towards that

end that you had described for yourself, interesting and mysterious things

happen. In your mind, the notes you’re working with end up being connected

in a perfect way to the notes that you had set out for the end of the piece.

It’s this working of the mind through these various possibilities that

eventually gets you there. But sometimes you do decide on the end of

the piece ahead of time, and when you’re working through, the material says, “No,

this is not the end of this piece. This piece has to end in this

way!” So you throw that idea away, and you

work your way through to a new end.

BD: Do you throw it away or do you save it

for another piece?

PR: [Laughs] I throw very little away.

Waste not, want not! I keep stacks of things. If I thought

it was a really good idea, then I’ll keep tabs on where it is and where

it might be useful.

BD: Do you know before you start the piece

about how long it will take to construct it?

PR: Ah, yes! I’m a slow worker though. I

ponder a lot, and I like to have an uninterrupted time to work on a piece.

I guess we would all like to have uninterrupted time to work on whatever

it is we’re working on, but I generally would have to set aside something

like six months or so to work on a piece that’s over ten minutes long.

I just need time to sort through the material, what it means, how it’s

connected, where it might go, all those kinds of things. I don’t

do it in a hurry. I wish I could be faster, but I’m not.

* * *

* *

BD: When you give your piece to a chamber group,

or to the conductor to rehearse, are you one of these guys that keeps

nudging them and making corrections, or do you stay the hell out of the

way?

PR: Making corrections of what I’ve written?

PR: Making corrections of what I’ve written?

BD: Or influencing the interpretation.

That’s really two questions.

PR: No, I don’t mess with the piece until they’ve

done it, and usually I won’t do anything to it anyway. Once in

a while I’ll revise things, but I’m given to, as you put it, staying

the hell out of the way. If they have questions, I assume they’ll

ask me. Generally, performers are kind enough to invite you to a

rehearsal before they play the piece. Then they ask what you have

to say, or would you like them to do this or that? You do get a

chance to have your say, but generally I prefer to stay out of it until

they ask me something. I’ve always been this

way, and that works pretty well.

BD: We were talking a moment ago about time.

You’re teaching and you’re composing. Do you get enough time to

compose?

PR: During the school year?

BD: Yes.

PR: Not really, unless it’s a fairly limited project

that I have saved time for, or that I could do during the school year.

If it were to be a revision, then that’s a fairly limited project and

I could work on that. But you try to isolate enough time during the

school year to do some work. It’s not always easy. I teach

at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, and the schedule we’re all

on helps somewhat. Our first term is over before Thanksgiving, and

then we don’t start again until after the New Year. So I can get five

weeks or so that I can work specifically on a project in the middle of

the year, which helps. Then we have the summer, and you get sabbatical

years.

BD: But basically you do your heaviest work

in the summer?

PR: Yes, because it’s just too many things

going on at once. There are always people to see, all those papers

to write, all those concerts to go to, so it takes your time.

BD: One of your biographies says you were

composer-in-residence in Cicero, Illinois. I was unaware that Cicero

had a composer-in-residence.

PR: During the late ’50s and

’60s, there was a program funded by the Ford Foundation

which was administered by MENC [Music Educators National Conference].

It was a program actually devised by the composer Norman Dello Joio,

and it was called ‘Composers in the Public Schools’. Composers from

all over the country were invited to apply for these grants. They

listened to your music, and you were interviewed, and the school systems

were interviewed, and they tried to match up composers and really excellent

school systems throughout the country. They’ve been all over the

country — in Cicero, in Anchorage, Alaska, in California,

or anywhere these is a good school system program. So I was sent

under this Ford Foundation MENC program to be composer-in-residence for

the J. Sterling Morton School System in Cicero. [The school district

is named for Julius Sterling Morton, Grover Cleveland’s

Secretary of Agriculture during his second term, who is best known for founding

Arbor Day.]

BD: Was that a satisfying experience?

BD: Was that a satisfying experience?

PR: Yes. I really enjoyed that because I

did teach public school music for a year after I finished graduate school

as a band director. I enjoyed the young players.

BD: Would that kind of thing work today, or

are we just too far removed from it?

PR: There has been a falling off of good

public school music programs because of cut-backs and school budgets.

So, it could work, but it would not work in so many places. There

would still some places left where it would work, and some of the states’

Arts Councils and Arts Boards have taken programs like that. They’ve

done it with poets for a while, but some of them do it with composers.

I think there’s a program in Minnesota run by the Minnesota Composers Forum.

[The MCF was established in 1973 by a group of graduate students from

the University of Minnesota, led by Libby Larsen and Stephen Paulus, with

a $400 grant from the Student Club Activities Fund. Its name was

changed in 1996 to the American Composers Forum. There are now about

2000 members in all 50 states, and over 500 titles have been released on

Innova, their recording label.]

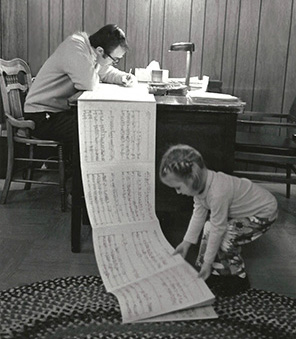

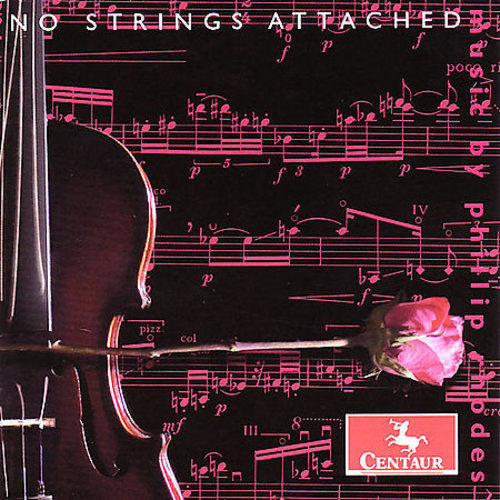

BD: Is composing fun?

PR: [Laughs] Yes, it can be an awful

lot of fun. Sometimes it can be an awful lot of work, especially

if you’re banging your head on a problem that doesn’t seem to want to

be resolved. But it’s becoming less physical hard work than it

used to be because of some of the aids with the computer music copying

programs. It used to be simply an enormous amount of physical work.

If you hand-copy a thirty-eight-stave orchestra score, and then copy all

the parts in ink by hand, being left-handed, as I am, you’re talking about

an enormous amount of physical labor... and that’s not to mention the four

or five times you’ve written a piece down in pencil while you’re working

on it. That’s changing now. Although my wife, bless her heart,

is trying to move me into the computer age, I resist the idea of composing

other than with pencil and paper. So I’m still using pencil and

paper, and then she gets to copy it on the computer! But some of the

younger composers have mastered the idea and the technique and feel of

composing at the computer, so the amount of physical hard work is less

than it was. But it’s still mental hard work to get some of these

things. From thirty-some years of doing it, I’ve learned that if you

get to four o’clock in the afternoon, and you’re up against a problem that

just won’t go away, it works for me to say, “OK,

I quit. I’ll look at it tomorrow,” and tomorrow’s

always better.

BD: Really???

PR: Yes, and tomorrow it gets fixed.

You think about it all night, but tomorrow it gets fixed.

BD: That gives you confidence to let it go

for a while?

PR: Well, you don’t let it go. You

have to keep enough notes around you to restructure the problem, but you

can just let go and say, “I’m not going to work

that now. I’ll fix that tomorrow.” And

if it doesn’t get fixed tomorrow, you say, “OK, I’ll

go beyond it and come back.” You learn how to

deal with how you work in thirty years. [Laughs]

BD: But eventually all the problems do get

solved?

PR: Pretty much. I would say yes, that’s

true.

BD: I wish you lots of continued success as a composer

and as a teacher. We need good teachers and good composers.

PR: I certainly would like to continue working

both. Thank you for having me. I’ve enjoyed this.

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on August 29, 1994.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in

2000. An unedited copy of the audio was placed in the Archive of

Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription

was made in 2017, and posted on this website early in 2018. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its final moment

as a classical station in February of

2001. His interviews have also appeared in

various magazines and journals since 1980, and he

now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information

about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century

ago. You may also

send him E-Mail with

comments, questions and suggestions.

BD: Does your music get older at all?

BD: Does your music get older at all?  PR: [Laughs] I don’t see why I have to reconcile

it at all.

PR: [Laughs] I don’t see why I have to reconcile

it at all. BD: What kinds of influence do you want to have on those

young minds?

BD: What kinds of influence do you want to have on those

young minds?  PR: Not completely different. There might be different

aspects of things she might focus on — the range,

for example, or kind of thing.

PR: Not completely different. There might be different

aspects of things she might focus on — the range,

for example, or kind of thing.  BD: Obviously, you have grown over the years. Do

you feel that the performers’ instincts and abilities

have also grown over the years?

BD: Obviously, you have grown over the years. Do

you feel that the performers’ instincts and abilities

have also grown over the years?  BD: Is there a point where they balance the technique

and the inspiration?

BD: Is there a point where they balance the technique

and the inspiration? PR: Making corrections of what I’ve written?

PR: Making corrections of what I’ve written?  BD: Was that a satisfying experience?

BD: Was that a satisfying experience?